Python自然语言处理学习笔记(12):2.4 词汇资源

Updated log

1st 2011.8.6

A lexicon, or lexical resource, is a collection of words and/or phrases along with associated information, such as part-of-speech(词性) and sense definitions. Lexical resources are secondary to texts, and are usually created and enriched with the help of texts. For example, if we have defined a text my_text, then vocab = sorted(set(my_text)) builds the vocabulary of my_text, whereas word_freq = FreqDist(my_text) counts the frequency of each word in the text. Both vocab and word_freq are simple lexical resources. Similarly, a concordance like the one we saw in Section 1.1 gives us information about word usage that might help in the preparation of a dictionary. Standard terminology(术语) for lexicons is illustrated in Figure 2-5. A lexical entry(词项) consists of a headword (词目,also known as a lemma ) along with additional information, such as the part-of-speech and the sense definition. Two distinct words having the same spelling are called homonyms(同形同音异义词).

Figure 2-5. Lexicon terminology: Lexical entries for two lemmas having the same spelling (homonyms), providing part-of-speech and gloss information.两个词目的词汇主体有相同的拼写,提供词性和注释信息。

The simplest kind of lexicon is nothing more than a sorted list of words. Sophisticated lexicons include complex structure within and across the individual entries. In this section, we’ll look at some lexical resources included with NLTK.

Wordlist Corpora Wordlist语料库

NLTK includes some corpora that are nothing more than wordlists. The Words Corpus is the /usr/dict/words file from Unix, used by some spellcheckers. We can use it to find unusual or misspelled words in a text corpus, as shown in Example 2-3.

Example 2-3. Filtering a text: This program computes the vocabulary of a text, then removes all items that occur in an existing wordlist, leaving just the uncommon or misspelled words.

text_vocab = set(w.lower() for w in text if w.isalpha())

english_vocab = set(w.lower() for w in nltk.corpus.words.words())

unusual = text_vocab.difference(english_vocab)

return sorted(unusual)

>>> unusual_words(nltk.corpus.gutenberg.words( ' austen-sense.txt ' ))

[ ' abbeyland ' , ' abhorrence ' , ' abominably ' , ' abridgement ' , ' accordant ' , ' accustomary ' ,

' adieus ' , ' affability ' , ' affectedly ' , ' aggrandizement ' , ' alighted ' , ' allenham ' ,

' amiably ' , ' annamaria ' , ' annuities ' , ' apologising ' , ' arbour ' , ' archness ' , ...]

>>> unusual_words(nltk.corpus.nps_chat.words())

[ ' aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa ' , ' aaahhhh ' , ' abou ' , ' abourted ' , ' abs ' , ' ack ' , ' acros ' ,

' actualy ' , ' adduser ' , ' addy ' , ' adoted ' , ' adreniline ' , ' ae ' , ' afe ' , ' affari ' , ' afk ' ,

' agaibn ' , ' agurlwithbigguns ' , ' ahah ' , ' ahahah ' , ' ahahh ' , ' ahahha ' , ' ahem ' , ' ahh ' , ...]

>>> stopwords.words( ' english ' )

[ ' a ' , " a's " , ' able ' , ' about ' , ' above ' , ' according ' , ' accordingly ' , ' across ' ,

' actually ' , ' after ' , ' afterwards ' , ' again ' , ' against ' , " ain't " , ' all ' , ' allow ' ,

' allows ' , ' almost ' , ' alone ' , ' along ' , ' already ' , ' also ' , ' although ' , ' always ' , ...]

Let’s define a function to compute what fraction of words in a text are not in the stopwords list:

... stopwords = nltk.corpus.stopwords.words( ' english ' )

... content = [w for w in text if w.lower() not in stopwords]

... return len(content) / len(text)

...

>>> content_fraction(nltk.corpus.reuters.words())

0.65997695393285261

Thus, with the help of stopwords, we filter out a third of the words of the text. Notice that we’ve combined two different kinds of corpus here, using a lexical resource to filter the content of a text corpus.

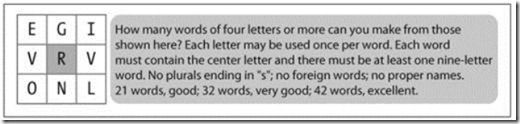

Figure 2-6. A word puzzle: A grid of randomly chosen letters with rules for creating words out of the letters; this puzzle is known as “Target.”

A wordlist is useful for solving word puzzles, such as the one in Figure 2-6. Our program iterates through every word and, for each one, checks whether it meets the conditions. It is easy to check obligatory(强制的) letter②and length①constraints (and we’ll only look for words with six or more letters here). It is trickier to check that candidate solutions only use combinations of the supplied letters, especially since some of the supplied letters appear twice (here, the letter v). The FreqDist comparison method③ permits us to check that the frequency of each letter in the candidate word is less than or equal to the frequency of the corresponding letter in the puzzle.(频率要小于或等于puzzle中的字母频率)

>>> obligatory = ' r '

>>> wordlist = nltk.corpus.words.words()

>>> [w for w in wordlist if len(w) >= 6

... and obligatory in w

... and nltk.FreqDist(w) <= puzzle_letters]

[ ' glover ' , ' gorlin ' , ' govern ' , ' grovel ' , ' ignore ' , ' involver ' , ' lienor ' ,

' linger ' , ' longer ' , ' lovering ' , ' noiler ' , ' overling ' , ' region ' , ' renvoi ' ,

' revolving ' , ' ringle ' , ' roving ' , ' violer ' , ' virole ' ]

One more wordlist corpus is the Names Corpus, containing 8,000 first names categorized by gender. The male and female names are stored in separate files. Let’s find names that appear in both files, i.e., names that are ambiguous for gender:

>>> names.fileids()

[ ' female.txt ' , ' male.txt ' ]

>>> male_names = names.words( ' male.txt ' )

>>> female_names = names.words( ' female.txt ' )

>>> [w for w in male_names if w in female_names]

[ ' Abbey ' , ' Abbie ' , ' Abby ' , ' Addie ' , ' Adrian ' , ' Adrien ' , ' Ajay ' , ' Alex ' , ' Alexis ' ,

' Alfie ' , ' Ali ' , ' Alix ' , ' Allie ' , ' Allyn ' , ' Andie ' , ' Andrea ' , ' Andy ' , ' Angel ' ,

' Angie ' , ' Ariel ' , ' Ashley ' , ' Aubrey ' , ' Augustine ' , ' Austin ' , ' Averil ' , ...]

It is well known that names ending in the letter a are almost always female(我不知道…). We can see this and some other patterns in the graph in Figure 2-7, produced by the following code. Remember that name[-1] is the last letter of name.

... (fileid, name[ - 1 ])

... for fileid in names.fileids()

... for name in names.words(fileid))

>>> cfd.plot()

Figure 2-7. Conditional frequency distribution: This plot shows the number of female and male names ending with each letter of the alphabet; most names ending with a, e, or i are female; names ending in h and l are equally likely to be male or female; names ending in k, o, r, s, and t are likely to be male.

A Pronouncing Dictionary 发音的词典

A slightly richer kind of lexical resource is a table (or spreadsheet 电子表格), containing a word plus some properties in each row. NLTK includes the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary for U.S. English, which was designed for use by speech synthesizers.

>>> len(entries)

127012

>>> for entry in entries[ 39943 : 39951 ]:

... print entry

...

( ' fir ' , [ ' F ' , ' ER1 ' ])

( ' fire ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' ER0 ' ])

( ' fire ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' R ' ])

( ' firearm ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' ER0 ' , ' AA2 ' , ' R ' , ' M ' ])

( ' firearm ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' R ' , ' AA2 ' , ' R ' , ' M ' ])

( ' firearms ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' ER0 ' , ' AA2 ' , ' R ' , ' M ' , ' Z ' ])

( ' firearms ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' R ' , ' AA2 ' , ' R ' , ' M ' , ' Z ' ])

( ' fireball ' , [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' ER0 ' , ' B ' , ' AO2 ' , ' L ' ])

For each word, this lexicon provides a list of phonetic(语音的)codes—distinct labels for each contrastive sound—known as phones. Observe that fire has two pronunciations (in U.S. English): the one-syllable F AY1 R, and the two-syllable(音节) F AY1 ER0. The symbols in the CMU Pronouncing Dictionary are from the Arpabet, described in more detail at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arpabet .

Each entry consists of two parts, and we can process these individually using a more complex version of the for statement. Instead of writing for entry in entries:, we replace entry with two variable names, word, pron①. Now, each time through the loop, word is assigned the first part of the entry, and pron is assigned the second part of the entry:

... if len(pron) == 3 : ② # 看明白了pron可是一个List啊

... ph1, ph2, ph3 = pron ③

... if ph1 == ' P ' and ph3 == ' T ' :

... print word, ph2,

...

pait EY1 pat AE1 pate EY1 patt AE1 peart ER1 peat IY1 peet IY1 peete IY1 pert ER1

pet EH1 pete IY1 pett EH1 piet IY1 piette IY1 pit IH1 pitt IH1 pot AA1 pote OW1

pott AA1 pout AW1 puett UW1 purt ER1 put UH1 putt AH1

The program just shown scans the lexicon looking for entries whose pronunciation consists of three phones(单音)②. If the condition is true, it assigns the contents of pron to three new variables: ph1, ph2, and ph3. Notice the unusual form of the statement that does that work③.

Here’s another example of the same for statement, this time used inside a list comprehension. This program finds all words whose pronunciation ends with a syllable sounding like nicks. You could use this method to find rhyming(押韵的) words.

>>> [word for word, pron in entries if pron[ - 4 :] == syllable]

[ " atlantic's " , ' audiotronics ' , ' avionics ' , ' beatniks ' , ' calisthenics ' , ' centronics ' ,

' chetniks ' , " clinic's " , ' clinics ' , ' conics ' , ' cynics ' , ' diasonics ' , " dominic's " ,

' ebonics ' , ' electronics ' , " electronics' " , ' endotronics ' , " endotronics' " , ' enix ' , ...]

Notice that the one pronunciation is spelled in several ways: nics, niks, nix, and even ntic’s with a silent t, for the word atlantic’s. Let’s look for some other mismatches between pronunciation and writing. Can you summarize the purpose of the following examples and explain how they work?

Notice that the one pronunciation is spelled in several ways: nics, niks, nix, and even ntic’s with a silent t, for the word atlantic’s. Let’s look for some other mismatches between pronunciation and writing. Can you summarize the purpose of the following examples and explain how they work?

[ ' autumn ' , ' column ' , ' condemn ' , ' damn ' , ' goddamn ' , ' hymn ' , ' solemn ' ]

>>> sorted(set(w[: 2 ] for w, pron in entries if pron[0] == ' N ' and w[0] != ' n ' ))

[ ' gn ' , ' kn ' , ' mn ' , ' pn ' ]

The phones contain digits to represent primary stress(主重音)(1), secondary stress (2), and no stress (0). As our final example, we define a function to extract the stress digits and then scan our lexicon to find words having a particular stress pattern.

... return [char for phone in pron for char in phone if char.isdigit()]

>>> [w for w, pron in entries if stress(pron) == [ ' 0 ' , ' 1 ' , ' 0 ' , ' 2 ' , ' 0 ' ]]

[ ' abbreviated ' , ' abbreviating ' , ' accelerated ' , ' accelerating ' , ' accelerator ' ,

' accentuated ' , ' accentuating ' , ' accommodated ' , ' accommodating ' , ' accommodative ' ,

' accumulated ' , ' accumulating ' , ' accumulative ' , ' accumulator ' , ' accumulators ' , ...]

>>> [w for w, pron in entries if stress(pron) == [ ' 0 ' , ' 2 ' , ' 0 ' , ' 1 ' , ' 0 ' ]]

[ ' abbreviation ' , ' abbreviations ' , ' abomination ' , ' abortifacient ' , ' abortifacients ' ,

' academicians ' , ' accommodation ' , ' accommodations ' , ' accreditation ' , ' accreditations ' ,

' accumulation ' , ' accumulations ' , ' acetylcholine ' , ' acetylcholine ' , ' adjudication ' , ...]

A subtlety(精妙) of this program is that our user-defined function stress() is invoked inside the condition of a list comprehension. There is also a doubly nested for loop. There’s a lot going on(发生) here, and you might want to return to this once you’ve had more experience using list comprehensions.

We can use a conditional frequency distribution to help us find minimally contrasting sets of words. Here we find all the p words consisting of three sounds②, and group them according to their first and last sounds①.

... for (word, pron) in entries

... if pron[0] == ' P ' and len(pron) == 3 ] ②

>>> cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist(p3)

>>> for template in cfd.conditions():

... if len(cfd[template]) > 10 :

... words = cfd[template].keys()

... wordlist = ' ' .join(words)

... print template, wordlist[: 70 ] + " ... "

...

P - CH perch puche poche peach petsche poach pietsch putsch pautsch piche pet...

P - K pik peek pic pique paque polk perc poke perk pac pock poch purk pak pa...

P - L pil poehl pille pehl pol pall pohl pahl paul perl pale paille perle po...

P - N paine payne pon pain pin pawn pinn pun pine paign pen pyne pane penn p...

P - P pap paap pipp paup pape pup pep poop pop pipe paape popp pip peep pope...

P - R paar poor par poore pear pare pour peer pore parr por pair porr pier...

P - S pearse piece posts pasts peace perce pos pers pace puss pesce pass pur...

P - T pot puett pit pete putt pat purt pet peart pott pett pait pert pote pa...

P - Z pays p.s pao ' s pais paws p. ' s pas pez paz pei ' s pose poise peas paiz p...

Rather than iterating over the whole dictionary, we can also access it by looking up particular words. We will use Python’s dictionary data structure, which we will study systematically in Section 5.3. We look up a dictionary by specifying its name, followed by a key (such as the word 'fire') inside square brackets①(也就是字典).

>>> prondict[ ' fire ' ] ①

[[ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' ER0 ' ], [ ' F ' , ' AY1 ' , ' R ' ]]

>>> prondict[ ' blog ' ] ②

Traceback (most recent call last):

File " <stdin> " , line 1 , in < module >

KeyError: ' blog '

>>> prondict[ ' blog ' ] = [[ ' B ' , ' L ' , ' AA1 ' , ' G ' ]] ③

>>> prondict[ ' blog ' ]

[[ ' B ' , ' L ' , ' AA1 ' , ' G ' ]]

If we try to look up a non-existent key②, we get a KeyError. This is similar to what happens when we index a list with an integer that is too large, producing an IndexError. The word blog is missing from the pronouncing dictionary, so we tweak ([俚语]【计算机】对…稍作调整)our version by assigning a value for this key③ (this has no effect on the NLTK corpus; next time we access it, blog will still be absent 因为修改的仅是存在于内存中的列表).

We can use any lexical resource to process a text, e.g., to filter out words having some lexical property (like nouns), or mapping every word of the text. For example, the following text-to-speech function looks up each word of the text in the pronunciation dictionary:

>>> [ph for w in text for ph in prondict[w][0]]

[ ' N ' , ' AE1 ' , ' CH ' , ' ER0 ' , ' AH0 ' , ' L ' , ' L ' , ' AE1 ' , ' NG ' , ' G ' , ' W ' , ' AH0 ' , ' JH ' ,

' P ' , ' R ' , ' AA1 ' , ' S ' , ' EH0 ' , ' S ' , ' IH0 ' , ' NG ' ]

Comparative Wordlists 比较的Wordlist

Another example of a tabular lexicon is the comparative wordlist. NLTK includes so-called Swadesh wordlists(斯瓦迪士核心词列表), lists of about 200 common words in several languages. The languages are identified using an ISO 639 two-letter code.

>>> swadesh.fileids()

[ ' be ' , ' bg ' , ' bs ' , ' ca ' , ' cs ' , ' cu ' , ' de ' , ' en ' , ' es ' , ' fr ' , ' hr ' , ' it ' , ' la ' , ' mk ' ,

' nl ' , ' pl ' , ' pt ' , ' ro ' , ' ru ' , ' sk ' , ' sl ' , ' sr ' , ' sw ' , ' uk ' ]

>>> swadesh.words( ' en ' )

[ ' I ' , ' you (singular), thou ' , ' he ' , ' we ' , ' you (plural) ' , ' they ' , ' this ' , ' that ' ,

' here ' , ' there ' , ' who ' , ' what ' , ' where ' , ' when ' , ' how ' , ' not ' , ' all ' , ' many ' , ' some ' ,

' few ' , ' other ' , ' one ' , ' two ' , ' three ' , ' four ' , ' five ' , ' big ' , ' long ' , ' wide ' , ...]

We can access cognate words(同源词)from multiple languages using the entries() method, specifying a list of languages. With one further step we can convert this into a simple dictionary (we’ll learn about dict() in Section 5.3).

>>> fr2en

[( ' je ' , ' I ' ), ( ' tu, vous ' , ' you (singular), thou ' ), ( ' il ' , ' he ' ), ...]

>>> translate = dict(fr2en)

>>> translate[ ' chien ' ]

' dog '

>>> translate[ ' jeter ' ]

' throw '

We can make our simple translator more useful by adding other source languages. Let’s get the German-English and Spanish-English pairs, convert each to a dictionary using dict(), then update our original translate dictionary with these additional mappings:

>>> es2en = swadesh.entries([ ' es ' , ' en ' ]) # Spanish-English

>>> translate.update(dict(de2en))

>>> translate.update(dict(es2en))

>>> translate[ ' Hund ' ]

' dog '

>>> translate[ ' perro ' ]

' dog '

We can compare words in various Germanic and Romance languages:

>>> languages = [ ' en ' , ' de ' , ' nl ' , ' es ' , ' fr ' , ' pt ' , ' la ' ]

>>> for i in [ 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 ]:

... print swadesh.entries(languages)[i]

...

( ' say ' , ' sagen ' , ' zeggen ' , ' decir ' , ' dire ' , ' dizer ' , ' dicere ' )

( ' sing ' , ' singen ' , ' zingen ' , ' cantar ' , ' chanter ' , ' cantar ' , ' canere ' )

( ' play ' , ' spielen ' , ' spelen ' , ' jugar ' , ' jouer ' , ' jogar, brincar ' , ' ludere ' )

( ' float ' , ' schweben ' , ' zweven ' , ' flotar ' , ' flotter ' , ' flutuar, boiar ' , ' fluctuare ' )

Shoebox and Toolbox Lexicons 词汇Shoebox和工具箱

Perhaps the single most popular tool used by linguists for managing data is Toolbox, previously known as Shoebox since it replaces the field linguist’s traditional shoebox full of file cards.

Toolbox is freely downloadable from http://www.sil.org/computing/toolbox/ .

A Toolbox file consists of a collection of entries, where each entry is made up of one or more fields. Most fields are optional or repeatable, which means that this kind of lexical resource cannot be treated as a table or spreadsheet.

Here is a dictionary for the Rotokas language. We see just the first entry, for the word kaa, meaning “to gag”:

>>> toolbox.entries( ' rotokas.dic ' )

[( ' kaa ' , [( ' ps ' , ' V ' ), ( ' pt ' , ' A ' ), ( ' ge ' , ' gag ' ), ( ' tkp ' , ' nek i pas ' ),

( ' dcsv ' , ' true ' ), ( ' vx ' , ' 1 ' ), ( ' sc ' , ' ??? ' ), ( ' dt ' , ' 29/Oct/2005 ' ),

( ' ex ' , ' Apoka ira kaaroi aioa-ia reoreopaoro. ' ),

( ' xp ' , ' Kaikai i pas long nek bilong Apoka bikos em i kaikai na toktok. ' ),

( ' xe ' , ' Apoka is gagging from food while talking. ' )]), ...]

Entries consist of a series of attribute-value pairs, such as ('ps', 'V') to indicate that the part-of-speech is 'V' (verb), and ('ge', 'gag') to indicate that the gloss-into-English is 'gag'. The last three pairs contain an example sentence in Rotokas and its translations into Tok Pisin and English.

The loose structure of Toolbox files makes it hard for us to do much more with them at this stage(现阶段). XML provides a powerful way to process this kind of corpus, and we will return to this topic in Chapter 11.

The Rotokas language is spoken on the island of Bougainville(布干维尔岛), Papua New Guinea(巴布亚新几内亚). This lexicon was contributed to NLTK by Stuart Robinson. Rotokas is notable for having an inventory of just 12 phonemes(音素) (contrastive sounds); see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotokas_language