Python自然语言处理学习笔记(43):5.4 自动标注

5.4 Automatic Tagging 自动标注

In the rest of this chapter we will explore various ways to automatically add part-of-speech tags to text. We will see that the tag of a word depends on the word and its context within a sentence. For this reason, we will be working with data at the level of (tagged) sentences rather than words. We’ll begin by loading the data we will be using.

>>> brown_tagged_sents = brown.tagged_sents(categories = ' news ' )

>>> brown_sents = brown.sents(categories = ' news ' )

The Default Tagger 缺省下的标注器

The simplest possible tagger assigns the same tag to each token. This may seem to be a rather banal(平庸的) step, but it establishes an important baseline(底线) for tagger performance. In order to get the best result, we tag each word with the most likely tag. Let’s find out which tag is most likely (now using the unsimplified tagset):

>>> nltk.FreqDist(tags).max()

' NN '

Now we can create a tagger that tags everything as NN.

>>> raw = ' I do not like green eggs and ham, I do not like them Sam I am! '

>>> tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(raw)

>>> default_tagger = nltk.DefaultTagger( ' NN ' )

>>> default_tagger.tag(tokens)

[( ' I ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' do ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' not ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' like ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' green ' , ' NN ' ),

( ' eggs ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' and ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' ham ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' , ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' I ' , ' NN ' ),

( ' do ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' not ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' like ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' them ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' Sam ' , ' NN ' ),

( ' I ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' am ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' ! ' , ' NN ' )]

Unsurprisingly, this method performs rather poorly. On a typical corpus, it will tag only about an eighth of(八分之一的正确率)the tokens correctly, as we see here:

0.13089484257215028

Default taggers assign their tag to every single word, even words that have never been encountered before. As it happens, once we have processed several thousand words of English text, most new words will be nouns. As we will see, this means that default taggers can help to improve the robustness of a language processing system. We will return to them shortly.

The Regular Expression Tagger 正则表达式标注器

The regular expression tagger assigns tags to tokens on the basis of matching patterns. For instance, we might guess that any word ending in ed is the past participle of a verb, and any word ending with ’s is a possessive noun(名词所有格). We can express these as a list of regular expressions:

(r ' .*ing$ ' , ' VBG ' ), # gerunds

(r ' .*ed$ ' , ' VBD ' ), # simple past

(r ' .*es$ ' , ' VBZ ' ), # 3rd singular present

(r ' .*ould$ ' , ' MD ' ), # modals

(r ' .*\'s$ ' , ' NN$ ' ), # possessive nouns

(r ' .*s$ ' , ' NNS ' ), # plural nouns

(r ' ^-?[0-9]+(.[0-9]+)?$ ' , ' CD ' ), # cardinal numbers

(r ' .* ' , ' NN ' ) # nouns (default)

... ]

Note that these are processed in order, and the first one that matches is applied. Now we can set up a tagger and use it to tag a sentence. After this step, it is correct about a fifth of the time.(五分之一了!)

>>> regexp_tagger.tag(brown_sents[ 3 ])

[( ' `` ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' Only ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' a ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' relative ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' handful ' , ' NN ' ),

( ' of ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' such ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' reports ' , ' NNS ' ), ( ' was ' , ' NNS ' ), ( ' received ' , ' VBD ' ),

( " '' " , ' NN ' ), ( ' , ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' the ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' jury ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' said ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' , ' , ' NN ' ),

( ' `` ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' considering ' , ' VBG ' ), ( ' the ' , ' NN ' ), ( ' widespread ' , ' NN ' ), ...]

>>> regexp_tagger.evaluate(brown_tagged_sents)

0.20326391789486245

The final regular expression «.*» is a catch-all that tags everything as a noun. This is equivalent to the default tagger (only much less efficient). Instead of respecifying this as part of the regular expression tagger, is there a way to combine this tagger with the default tagger? We will see how to do this shortly.

Your Turn: See if you can come up with patterns to improve the performance of the regular expression tagger just shown. (Note that Section 6.1 describes a way to partially automate such work.)

The Lookup Tagger 查询标注器

A lot of high-frequency words do not have the NN tag. Let’s find the hundred most frequent words and store their most likely tag. We can then use this information as the model for a “lookup tagger” (an NLTK UnigramTagger):

>>> cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist(brown.tagged_words(categories = ' news ' ))

>>> most_freq_words = fd.keys()[: 100 ]

>>> likely_tags = dict((word, cfd[word].max()) for word in most_freq_words)

>>> baseline_tagger = nltk.UnigramTagger(model = likely_tags)

>>> baseline_tagger.evaluate(brown_tagged_sents)

0.45578495136941344

It should come as no surprise by now that simply knowing the tags for the 100 most frequent words enables us to tag a large fraction of tokens correctly (nearly half, in fact).

Let’s see what it does on some untagged input text:

>>> baseline_tagger.tag(sent)

[( ' `` ' , ' `` ' ), ( ' Only ' , None), ( ' a ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' relative ' , None),

( ' handful ' , None), ( ' of ' , ' IN ' ), ( ' such ' , None), ( ' reports ' , None),

( ' was ' , ' BEDZ ' ), ( ' received ' , None), ( " '' " , " '' " ), ( ' , ' , ' , ' ),

( ' the ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' jury ' , None), ( ' said ' , ' VBD ' ), ( ' , ' , ' , ' ),

( ' `` ' , ' `` ' ), ( ' considering ' , None), ( ' the ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' widespread ' , None),

( ' interest ' , None), ( ' in ' , ' IN ' ), ( ' the ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' election ' , None),

( ' , ' , ' , ' ), ( ' the ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' number ' , None), ( ' of ' , ' IN ' ),

( ' voters ' , None), ( ' and ' , ' CC ' ), ( ' the ' , ' AT ' ), ( ' size ' , None),

( ' of ' , ' IN ' ), ( ' this ' , ' DT ' ), ( ' city ' , None), ( " '' " , " '' " ), ( ' . ' , ' . ' )]

Many words have been assigned a tag of None, because they were not among the 100 most frequent words. In these cases we would like to assign the default tag of NN. In other words, we want to use the lookup table first, and if it is unable to assign a tag, then use the default tagger, a process known as backoff (备值)(Section 5.5). We do this by specifying one tagger as a parameter to the other, as shown next. Now the lookup tagger will only store word-tag pairs for words other than nouns, and whenever it cannot assign a tag to a word, it will invoke the default tagger.

... backoff = nltk.DefaultTagger( ' NN ' ))

Let’s put all this together and write a program to create and evaluate lookup taggers having a range of sizes (Example 5-4).

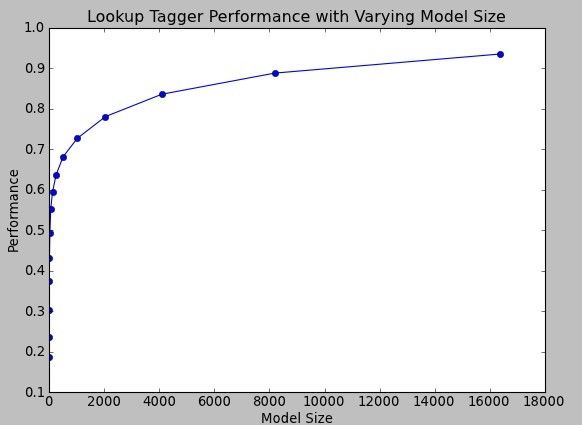

Example 5-4. Lookup tagger performance with varying model size.

lt = dict((word, cfd[word].max()) for word in wordlist)

baseline_tagger = nltk.UnigramTagger(model = lt, backoff = nltk.DefaultTagger( ' NN ' ))

return baseline_tagger.evaluate(brown.tagged_sents(categories = ' news ' ))

def display():

import pylab

words_by_freq = list(nltk.FreqDist(brown.words(categories = ' news ' )))

cfd = nltk.ConditionalFreqDist(brown.tagged_words(categories = ' news ' ))

sizes = 2 ** pylab.arange( 15 )

perfs = [performance(cfd, words_by_freq[:size]) for size in sizes]

pylab.plot(sizes, perfs, ' -bo ' )

pylab.title( ' Lookup Tagger Performance with Varying Model Size ' )

pylab.xlabel( ' Model Size ' )

pylab.ylabel( ' Performance ' )

pylab.show()

>>> display()

Observe in Figure 5-4 that performance initially increases rapidly as the model size grows, eventually reaching a plateau(稳定水平), when large increases in model size yield little improvement in performance. (This example used the pylab plotting package, discussed in Section 4.8.)

Figure 5-4. Lookup tagger

Evaluation 评价

In the previous examples, you will have noticed an emphasis on accuracy scores. In fact, evaluating the performance of such tools is a central theme in NLP. Recall the processing pipeline in Figure 1-5; any errors in the output of one module are greatly multiplied in the downstream modules(一个模块上的任何一个错误在下游的模块中会被大大增加).

We evaluate the performance of a tagger relative to the tags a human expert would assign. Since we usually don’t have access to(接近) an expert and impartial(公正的) human judge, we make do instead with gold standard test data. This is a corpus which has been manually annotated and accepted as a standard against which the guesses of an automatic system are assessed. The tagger is regarded as being correct if the tag it guesses for a given word is the same as the gold standard tag.

Of course, the humans who designed and carried out the original gold standard annotation were only human. Further analysis might show mistakes in the gold standard, or may eventually lead to a revised(改进的) tagset and more elaborate(详细制作) guidelines. Nevertheless, the gold standard is by definition “correct” as far as(就...而言) the evaluation of an automatic tagger is concerned.

Developing an annotated corpus is a major undertaking(保证). Apart from the data, it generates sophisticated tools, documentation, and practices for ensuring high-quality annotation. The tagsets and other coding schemes inevitably depend on some theoretical position that is not shared by all. However, corpus creators often go to great lengths to make their work as theory-neutral(中性理论) as possible in order to maximize the usefulness of their work. We will discuss the challenges of creating a corpus in Chapter 11.