Streamlined

Disney, AT&T and Comcast v Netflix, Amazon and Apple

In the entertainment wars, billions of dollars are being torched. Someone will get hurt

WHO MIGHT buy Netflix? Speculation on the matter has risen in line with the streaming giant’s own ascent in the past decade. Apple, with its cash hoard, was a frequently rumoured suitor. Or perhaps Amazon, or big distributors like AT&T or Comcast. At one point, industry sources say, Bob Iger of Disney directly asked Reed Hastings, the boss of Netflix, if he would welcome an offer (Mr Hastings said no).

Instead all six companies embarked on a series of massive investments that will reshape the landscape of media: who makes entertainment and how people consume it. Since June AT&T, Comcast and Disney have spent $215bn in total on acquisitions of, respectively, Time Warner ($104bn), Sky, a European broadcaster ($40bn), and much of 21st Century Fox ($71bn). Each is preparing new streaming services that will launch by early 2020.

Apple, meanwhile, has poured perhaps $2bn into original shows with some of Hollywood’s most famous directors and stars. On March 25th the company unveiled its new streaming-video service, Apple TV+, that will be available in more than 100 countries later this year. Amazon is thought to be spending more than $5bn a year on content. And Netflix is expected to burn about $15bn this year on original and licensed content in a bid to add to its 139m global subscribers before most of its would-be rivals get fully up and running.

The firms are chasing the same prize: recurring revenue from video subscriptions by tens of millions of Americans and, potentially, hundreds of millions of international viewers. It is unclear how many of them can thrive at the same time. More than two, analysts reckon, but not all six. There are only so many $10 monthly subscriptions people will pay for. They may opt once again for those bundled with something else, like a mobile service—a business model of which consumers had grown weary in America, where a single distributor sells lots of channels at one price. What forms these reimagined bundles take, and who gets to sell them, will depend on who wins the streaming battles.

In this fight, the contenders have adopted different strategies to win over subscribers. AT&T will bundle entertainment with its mobile service, which could help the company overtake Verizon as the largest wireless carrier in America. Comcast will offer an ad-supported streaming service from NBCUniversal, which it owns, to its 52m broadband and pay-TV customers (including Sky’s) in America, Britain and elsewhere in Europe (it will also sell subscriptions, but its ambitions seem more modest than the others’). Disney will use its enviable collection of film franchises, including Star Wars and Marvel superheroes, to draw families to Disney+, then steer them to its consumer products and theme parks.

For the tech giants, video is a way to lure customers into their online emporiums. Amazon, with 100m Prime households, is ahead of Apple for now. But Apple TV can push its glitzy new shows to the world’s 1.4bn iDevices. Apple and Amazon have deeper pockets than AT&T, Comcast or Disney, so can afford to pour billions annually into streaming-video for years to come. Their platforms are perfect for selling online services including video.

Then there is Netflix. Its head start puts it in a strong position. Its algorithms work out what viewers want and it has the infrastructure to deliver it to ever more people. A recession or rising interest rates could hurt its ability to borrow—Netflix has more than $10bn in debt and burns through $3bn of cash a year. But its lead is such that it could curtail spending on content and still stay ahead of competitors.

AT&T and Disney face a more complicated challenge. To prosper in streaming, they must undermine lucrative existing businesses. In AT&T’s business unit that houses DirecTV, a satellite provider acquired in 2015 at a cost of $63bn, operating income has fallen by 20% since 2016—in part owing to aggressive marketing of DirecTV Now, a cheaper, loss-making streaming bundle of pay-TV networks. The new streaming service from AT&T (marketed under the WarnerMedia brand) will exacerbate the decline. Disney, for its part, will forgo profits of about $1bn this year—and $2bn annually from 2020—as it stops licensing films to Netflix and invests in original shows for its streaming platform, Disney+. New investments in Hulu, a general-interest streaming service with 25m subscribers that Disney controls, will also be costly.

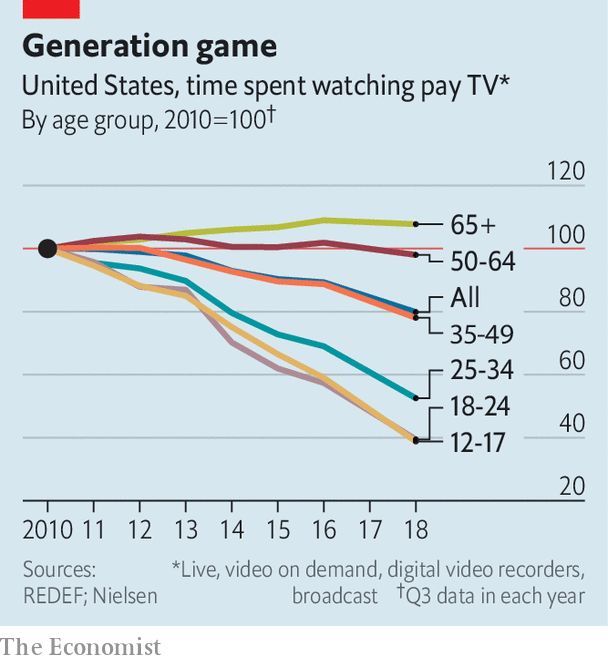

Disney and AT&T are willing to sacrifice near-term profits for two reasons: the vulnerability of their underlying businesses, and hoped-for returns from streaming. With the rise of Netflix, YouTube and other internet distractions, Americans are watching less pay-TV (see chart) and dropping pricey packages which AT&T sells, and which carry Disney’s TV networks. And they go to the cinema less often. That is why Rupert Murdoch wanted to sell much of his Fox empire, and Jeff Bewkes was keen to offload Time Warner. Networks bereft of “must-have” content will face demands from distributors to lower prices. Disney and AT&T viewed Fox and Time Warner studios and entertainment networks, with their libraries of hits, as valuable assets.

For Disney, which oozed popular content even before the Fox deal, the economics of streaming stack up. ESPN, Disney’s sports network, generates more than $2bn annually, according to Kagan, a research group. But its reach is declining. In 2018 the company launched ESPN+, a sports-streaming service. It has picked up 2m subscribers in less than a year (though it is expected to lose money for years).

The real opportunity should be in Disney+. Disney’s dominance of the box office will count for less as fewer people frequent cinemas. Matthew Ball, a media analyst, argues that even before the acquisition of Fox’s big franchises, such as “Avatar”, Disney’s spectaculars were beginning to crowd each other out. Streaming provides a neat solution. Disney will release films directly online, as with the upcoming live-action version of “Lady and the Tramp”, in addition to TV series from Lucasfilm, Marvel Studios and Pixar Animation. Once licences expire, it will control access to its complete library of hits. Bullish analysts at JPMorgan Chase, a bank, believe Disney+ can break even by 2022 and eventually attract 45m subscribers in America and 115m abroad. At $8-10 per month that would equate to $15bn-19bn in recurring sales; Disney’s revenues last fiscal year totalled $59bn. Disney would also have something new and valuable: direct relationships with its biggest fans.

AT&T and Comcast look more precarious. WarnerMedia (as Time Warner has been renamed) owns some famous superheroes, like Batman and Wonder Woman, but they are not quite so formidable as Disney’s. AT&T’s early handling of WarnerMedia, where several highly respected executives have resigned, most notably at HBO, its most important asset, has raised concerns about its ability to manage a giant media conglomerate. Comcast, meanwhile, lacks enough popular shows to grab subscribers’ attention.

It is not clear that owners of infrastructure need to enter the battle to produce content. Craig Moffett of MoffettNathanson, a research firm, argues that the streaming boom should benefit owners of distribution pipes. They can offset falling revenue from pay-TV with broadband, which offers higher margins with less capital spending. The cost of programming has ballooned—well above $10m an hour for “Game of Thrones”—as viewers increasingly expect blockbuster quality from their shows. One day, a Hollywood executive predicts, the spending binge will come to a halt. The streaming market, too, will consolidate. It will be “the biggest hangover that Hollywood has ever seen”.

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline "Streamlined"(Mar 28th 2019)

LearnAndRecord

2015年2月8日

2019年4月4日

第1517天

每天持续行动学外语