In Bicycle thieves, Antonio finally gets a job, but the bicycle, he used all his home for the necessary conditions for his job, was stolen on the first day of work. Ricci is looking around town with his six- year-old son. Finally, in a frenzy, he stole someone else's bicycle and ran away. But he was caught, beaten and scolded, and his son pulled his father's clothes to cry. The owner decided not to pursue the case. Desperate Antonio took his son's hand and slowly disappeared into the crowd. The narrative of the entire film provides the audience with specific representatives of post-war Italian society: unemployment, alienation, housing conditions, etc.

The first is the alienation of Marxism. According to Marx's theory of capitalism, any useful object of any kind that can meet human needs initially has the use-value and strong connection of the labour force. The qualitative use-value is transformed into the quantitative exchange value, which results in the formal transformation of the item into a commodity. When different goods enter the topic of exchange, different, specific labour also loses their qualitative aspects, and is configured as a concept of quantity. (Lombardi, 2009, pp118). Thus, the value of labour is materialized and attached to the goods it creates.

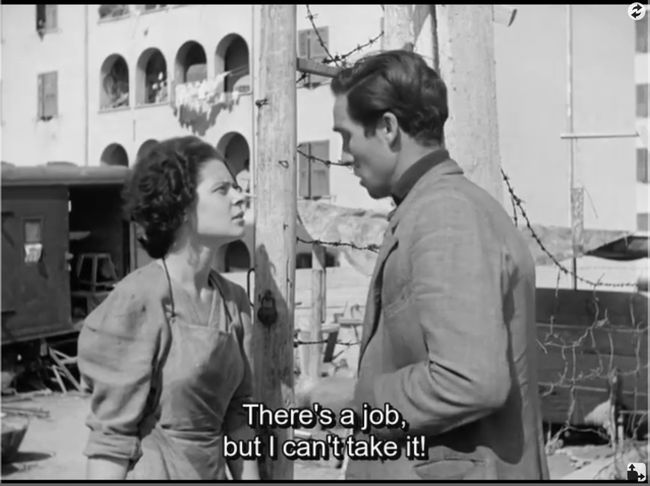

In the first half of the film, the man's bike moves almost step by step along the process of moving object to commodity. Initially, the bicycle was associated with its use value, and it represented the potential of the hero's labour, which was a necessary condition for his employment. This can be seen in the character's despair at losing it: “There’s a job, but I can’t take it.” He barked at his wife after returning from the unemployment office (00:04:30).

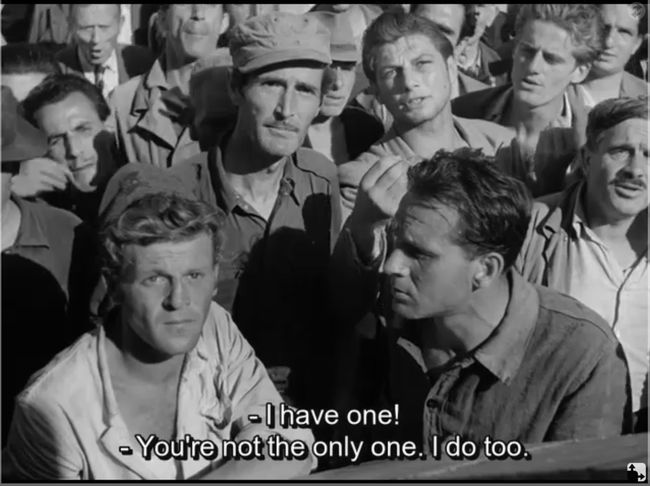

At the office, we learn that the hero and his bike are not unique. When the man and his bike can be exchanged with any other worker-bike combination, an early sign of the commercialized background of the narrative is revealed. In the visual narrative, other workers with bicycles are ready to accept the actor's failure:” You are not the only one, I’ve got one too.” (00:03:30) This line echoed the crowd and threatened Antonio. As labour and goods become exchangeable, their value becomes more and more tied to ruthless money, and the proliferation and fragmentation of central goods magnifies emptiness and the meaninglessness of the capitalist economy (Lombardi, 2009, pp121). The quest for the bicycle seems to have morphed into an alienated quest for the irreparable meaning of human labour itself.

The follow-up actor's search for his bicycle, however, hints at the inscriptions and narratives of Marxism's core criticism of capitalism: that the alienation of Labour from labourers is the result of the process of turning objects into commodities (Lombardi, 2009, pp118). In the pawnshop sequence, items are first "stained" by extended exchange values, heralding the desperate level of the bicycle market sequence that further underscores the now more alienated situation of items. The film's attempt is first and foremost an orderly division of labour, which divides people into three separates but virtually similar parts of the assembly line: Bruno looking for pumps and bells, Meniconi and Antonio looking for tires. Baiocco says “We’ll look for it piece by piece and then put it back together.” (00:31:54-00:31:56). However, the characters are reassembled several times throughout the episode, and the five of them always get together, like holding a group to keep warm. The alternating appearance of lost faces and footage of bicycle parts seems to emphasize the pointless effort of a similar division of labour. Beyond that, it is only by brand and code or other markers of the capitalist system in which the bikes live, that their excessive identity can be distinguished.

Hailed as "the only effective communist film of the past decade” (Tomasulo, 1982, pp4), Bicycle thieves’ two secondary plots revolve around defining inequality in socio-economic class." And, as the film shows, Antonio is the victim of a cold government whose restrictive monetary policy sets out the macro scope within which Antonio must operate. After the war, the republican state, which had largely suppressed the aristocracy and the big bourgeoisie, continued to suppress the working class by governing it through its bureaucracy and coercion of the state under the rule of law (Francese, 2020, pp242). For instance, when the male master reported the police were anxious to raid the Communist Party's rally, and then the male master went to the Italian Communist Party branch, the meeting opened hot a large group of people ignore him, several party members and friends to help him find the bicycle.

In fact, between 1946 and 1947, funds from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Refugees were used to build modern but overcrowded housing units. This measure, together with increased social assistance programs, pensions, and family allowances, helped to contain the social unrest caused by the abolition of the dismissal ban in July 1947. During this period, criticism of the Italian Communist Party, both explicit and implicit, revolves around the cooperation in the reconstruction of the Italian economy (Tomasulo, 1982, pp3). There is an undoubted connection between neo-realism and its social/historical moments, yet the film seems unable to deal with the real forces at work within society, so replace it and try to end the discussion around it. For example, while Biaocco was rehearsing in the basement, a group of communists entered the space and caused a riot. One of the singers, unable to find the right note, stepped forward and said “No, this is either a rehearsal or a meeting. “(00:29:37). This scene can be understood as illustrating the tension between art and politics, the main tension of the film. In addition, the singing of the lyrics of the songs was actually dealing with oppression, but the high-pitched debate replaced the aesthetic content of politics. This is a seemingly innocuous scene that can be symbolized as a textual dichotomy. As Lombardi (2009) said, the artificiality of the film, both narrative and visual, is presented in a delicate structure: play down the revolutionary elements of political interpretation.

The film is also frantically trying to dispel the myth of solidarity among the poor. This is the result of the betrayal of the man himself, the thief, the old man, his helpless friend, his son and the party leader, who is only concerned with the big problem. The historical fact of worker solidarity is carefully ignored.

References:

Francese, J. (2020). Of shame and humiliation in Ladri di biciclette: “Ciccio formaggio” and “Tammurriata nera.” Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies, 8(2), 237.

Lombardi, E. (2009). Of Bikes and Men: The intersection of three narratives in Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette. Studies in European Cinema, 6(2/3), 113–126. https://doi-org.ez.xjtlu.edu.cn/10.1386/seci.6.2-3.113/1

Tomasulo, P, F. (1982). Bicycle Thieves: A Re-Reading. Cinema Journal, 21(2), 1-13.