Think Python - Chapter 03 - Functions

3.1 Function calls

In the context of programming, a function is a named sequence of statements that performs a computation. When you define a function, you specify the name and the sequence of statements. Later, you can “call” the function by name. We have already seen one example of a function call:

>>> type(32) <type 'int'>

The name of the function is type. The expression in parentheses is called the argument of the function. The result, for this function, is the type of the argument. It is common to say that a function “takes” an argument and “returns” a result. The result is called the return value.

3.2 Type conversion functions

Python provides built-in functions that convert values from one type to another. The int function takes any value and converts it to an integer, if it can, or complains otherwise:

>>> int('32') 32 >>> int('Hello') ValueError: invalid literal for int(): Hello

int can convert floating-point values to integers, but it doesn’t round off; it chops off the fraction part:

>>> int(3.99999) 3 >>> int(-2.3) -2

float converts integers and strings to floating-point numbers:

>>> float(32) 32.0 >>> float('3.14159') 3.14159

Finally, str converts its argument to a string:

>>> str(32) '32' >>> str(3.14159) '3.14159'

3.3 Math functions

Python has a math module that provides most of the familiar mathematical functions. A module is a file that contains a collection of related functions. Before we can use the module, we have to import it:

>>> import math

This statement creates a module object named math. If you print the module object, you get some information about it:

>>> print math <module 'math' (built-in)>

The module object contains the functions and variables defined in the module. To access one of the functions, you have to specify the name of the module and the name of the function, separated by a dot (also known as a period). This format is called dot notation.

>>> ratio = signal_power / noise_power >>> decibels = 10 * math.log10(ratio) >>> radians = 0.7 >>> height = math.sin(radians)

The first example uses log10 to compute a signal-to-noise ratio in decibels (assuming that signal_power and noise_power are defined). The math module also provides log, which computes logarithms base e.

The second example finds the sine of radians. The name of the variable is a hint that sin and the other trigonometric functions (cos, tan, etc.) take arguments in radians. To convert from degrees to radians, divide by 360 and multiply by 2pi:

>>> degrees = 45 >>> radians = degrees / 360.0 * 2 * math.pi >>> math.sin(radians) 0.707106781187

The expression math.pi gets the variable pi from the math module. The value of this variable is an approximation of p, accurate to about 15 digits.

If you know your trigonometry, you can check the previous result by comparing it to the square root of two divided by two:

>>> math.sqrt(2) / 2.0 0.707106781187

3.4 Composition

So far, we have looked at the elements of a program—variables, expressions, and statements—in isolation, without talking about how to combine them.

One of the most useful features of programming languages is their ability to take small building blocks and compose them. For example, the argument of a function can be any kind of expression, including arithmetic operators:

x = math.sin(degrees / 360.0 * 2 * math.pi)

And even function calls:

x = math.exp(math.log(x+1))

Almost anywhere you can put a value, you can put an arbitrary expression, with one exception: the left side of an assignment statement has to be a variable name. Any other expression on the left side is a syntax error (we will see exceptions to this rule later).

>>> minutes = hours * 60 # right >>> hours * 60 = minutes # wrong! SyntaxError: can't assign to operator

3.5 Adding new functions

So far, we have only been using the functions that come with Python, but it is also possible to add new functions. A function definition specifies the name of a new function and the sequence of statements that execute when the function is called.

Here is an example:

def print_lyrics(): print "I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay." print "I sleep all night and I work all day."

def is a keyword that indicates that this is a function definition. The name of the function is print_lyrics. The rules for function names are the same as for variable names: letters, numbers and some punctuation marks are legal, but the first character can’t be a number.

You can’t use a keyword as the name of a function, and you should avoid having a variable and a function with the same name.(函数名可以和变量名相同?)

The empty parentheses after the name indicate that this function doesn’t take any arguments.

The first line of the function definition is called the header; the rest is called the body.

The header has to end with a colon and the body has to be indented. By convention, the indentation is always four spaces (see Section 3.14). The body can contain any number of statements.

The strings in the print statements are enclosed in double quotes. Single quotes and double quotes do the same thing; most people use single quotes except in cases like this where a single quote (which is also an apostrophe) appears in the string.

If you type a function definition in interactive mode, the interpreter prints ellipses (...) to let you know that the definition isn’t complete:

>>> def print_lyrics(): print "I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay." print "I sleep all night and I work all day."

To end the function, you have to enter an empty line (this is not necessary in a script).

Defining a function creates a variable with the same name.

>>> print print_lyrics <function print_lyrics at 0xb7e99e9c> >>> type(print_lyrics) <type 'function'>

The value of print_lyrics is a function object, which has type 'function'. The syntax for calling the new function is the same as for built-in functions:

>>> print_lyrics() I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay. I sleep all night and I work all day.

Once you have defined a function, you can use it inside another function. For example, to repeat the previous refrain, we could write a function called repeat_lyrics:

def repeat_lyrics(): print_lyrics() print_lyrics()

And then call repeat_lyrics:

>>> repeat_lyrics() I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay. I sleep all night and I work all day. I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay. I sleep all night and I work all day.

But that’s not really how the song goes.

3.6 Definitions and uses

Pulling together the code fragments from the previous section, the whole program looks like this:

def print_lyrics(): print "I'm a lumberjack, and I'm okay." print "I sleep all night and I work all day." def repeat_lyrics(): print_lyrics() print_lyrics() repeat_lyrics()

This program contains two function definitions: print_lyrics and repeat_lyrics. Function definitions get executed just like other statements, but the effect is to create function objects. The statements inside the function do not get executed until the function is called, and the function definition generates no output.

As you might expect, you have to create a function before you can execute it. In other words, the function definition has to be executed before the first time it is called.

Exercise 3.1. Move the last line of this program to the top, so the function call appears before the definitions. Run the program and see what error message you get.

Exercise 3.2. Move the function call back to the bottom and move the definition of print_lyrics after the definition of repeat_lyrics. What happens when you run this program?

3.7 Flow of execution

In order to ensure that a function is defined before its first use, you have to know the order in which statements are executed, which is called the flow of execution.

Execution always begins at the first statement of the program. Statements are executed one at a time, in order from top to bottom.

Function definitions do not alter the flow of execution of the program, but remember that statements inside the function are not executed until the function is called.

A function call is like a detour in the flow of execution. Instead of going to the next statement, the flow jumps to the body of the function, executes all the statements there, and then comes back to pick up where it left off.

That sounds simple enough, until you remember that one function can call another. While in the middle of one function, the program might have to execute the statements in another function. But while executing that new function, the program might have to execute yet another function!

Fortunately, Python is good at keeping track of where it is, so each time a function completes, the program picks up where it left off in the function that called it. When it gets to the end of the program, it terminates.

What’s the moral of this sordid tale? When you read a program, you don’t always want to read from top to bottom. Sometimes it makes more sense if you follow the flow of execution.

3.8 Parameters and arguments

Some of the built-in functions we have seen require arguments. For example, when you call math.sin you pass a number as an argument. Some functions take more than one argument: math.pow takes two, the base and the exponent.

Inside the function, the arguments are assigned to variables called parameters. Here is an example of a user-defined function that takes an argument:

def print_twice(bruce): print bruce print bruce

This function assigns the argument to a parameter named bruce. When the function is called, it prints the value of the parameter (whatever it is) twice.

This function works with any value that can be printed.

>>> print_twice('Spam') Spam Spam >>> print_twice(17) 17 17 >>> print_twice(math.pi) 3.14159265359 3.14159265359

The same rules of composition that apply to built-in functions also apply to user-defined functions, so we can use any kind of expression as an argument for print_twice:

>>> print_twice('Spam '*4) Spam Spam Spam Spam Spam Spam Spam Spam >>> print_twice(math.cos(math.pi)) -1.0 -1.0

The argument is evaluated before the function is called, so in the examples the expressions 'Spam '*4 and math.cos(math.pi) are only evaluated once.

You can also use a variable as an argument:

>>> michael = 'Eric, the half a bee.' >>> print_twice(michael) Eric, the half a bee. Eric, the half a bee.

The name of the variable we pass as an argument (michael) has nothing to do with the name of the parameter (bruce). It doesn’t matter what the value was called back home (in the caller); here in print_twice, we call everybody bruce.

3.9 Variables and parameters are local

When you create a variable inside a function, it is local, which means that it only exists inside the function. For example:

def cat_twice(part1, part2): cat = part1 + part2 print_twice(cat)

This function takes two arguments, concatenates them, and prints the result twice. Here is an example that uses it:

>>> line1 = 'Bing tiddle ' >>> line2 = 'tiddle bang.' >>> cat_twice(line1, line2) Bing tiddle tiddle bang. Bing tiddle tiddle bang.

When cat_twice terminates, the variable cat is destroyed. If we try to print it, we get an exception:

>>> print cat NameError: name 'cat' is not defined

Parameters are also local. For example, outside print_twice, there is no such thing as bruce.

3.10 Stack diagrams

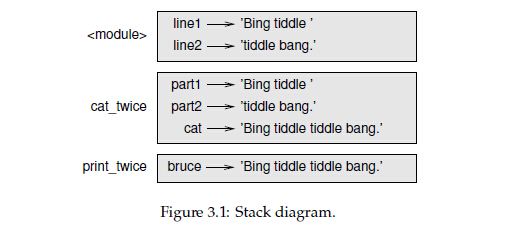

To keep track of which variables can be used where, it is sometimes useful to draw a stack diagram. Like state diagrams, stack diagrams show the value of each variable, but they also show the function each variable belongs to.

Each function is represented by a frame. A frame is a box with the name of a function beside it and the parameters and variables of the function inside it. The stack diagram for the previous example is shown in Figure 3.1.

The frames are arranged in a stack that indicates which function called which, and so on. In this example, print_twice was called by cat_twice, and cat_twice was called by __main__, which is a special name for the topmost frame. When you create a variable outside of any function, it belongs to __main__.

Each parameter refers to the same value as its corresponding argument. So, part1 has the same value as line1, part2 has the same value as line2, and bruce has the same value as cat.

If an error occurs during a function call, Python prints the name of the function, and the name of the function that called it, and the name of the function that called that, all the way back to __main__.

For example, if you try to access cat from within print_twice, you get a NameError:

Traceback (innermost last): File "test.py", line 13, in __main__ cat_twice(line1, line2) File "test.py", line 5, in cat_twice print_twice(cat) File "test.py", line 9, in print_twice print cat NameError: name 'cat' is not defined

This list of functions is called a traceback. It tells you what program file the error occurred in, and what line, and what functions were executing at the time. It also shows the line of code that caused the error.

The order of the functions in the traceback is the same as the order of the frames in the stack diagram. The function that is currently running is at the bottom.

3.11 Fruitful functions and void functions

Some of the functions we are using, such as the math functions, yield results; for lack of a better name, I call them fruitful functions. Other functions, like print_twice, perform an action but don’t return a value. They are called void functions.

When you call a fruitful function, you almost always want to do something with the result; for example, you might assign it to a variable or use it as part of an expression:

x = math.cos(radians)

golden = (math.sqrt(5) + 1) / 2

When you call a function in interactive mode, Python displays the result:

>>> math.sqrt(5)

2.2360679774997898

But in a script, if you call a fruitful function all by itself, the return value is lost forever!

math.sqrt(5)

This script computes the square root of 5, but since it doesn’t store or display the result, it is not very useful.

Void functions might display something on the screen or have some other effect, but they don’t have a return value. If you try to assign the result to a variable, you get a special value called None.

>>> result = print_twice('Bing') Bing Bing >>> print result None

The value None is not the same as the string 'None'. It is a special value that has its own type:

>>> print type(None) <type 'NoneType'>

The functions we have written so far are all void. We will start writing fruitful functions in a few chapters.

3.12 Why functions?

It may not be clear why it is worth the trouble to divide a program into functions. There are several reasons:

- Creating a new function gives you an opportunity to name a group of statements, which makes your program easier to read and debug.

- Functions can make a program smaller by eliminating repetitive code. Later, if you make a change, you only have to make it in one place.

- Dividing a long program into functions allows you to debug the parts one at a time and then assemble them into a working whole.

- Well-designed functions are often useful for many programs. Once you write and debug one, you can reuse it.

3.13 Importing with from

Python provides two ways to import modules; we have already seen one:

>>> import math >>> print math <module 'math' (built-in)> >>> print math.pi 3.14159265359

If you import math, you get a module object named math. The module object contains constants like pi and functions like sin and exp. But if you try to access pi directly, you get an error.

>>> print pi Traceback (most recent call last): File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module> NameError: name 'pi' is not defined

As an alternative, you can import an object from a module like this:

>>> from math import pi

Now you can access pi directly, without dot notation.

>>> print pi 3.14159265359

Or you can use the star operator to import everything from the module:

>>> from math import * >>> cos(pi) -1.0

The advantage of importing everything from the math module is that your code can be more concise. The disadvantage is that there might be conflicts between names defined in different modules, or between a name from a module and one of your variables.("from xxx import *"的优缺点)