Reverse-engineering Samsung S10 TEEGRIS TrustZone OS

Even though I have quite a lot of stuff I'm planning to write about, time is very limited.

Lately I've been working on reverse engineering and documenting

the S-Boot bootloader and TrustZone OS from the Exynos version

of Samsung Galaxy S10.

TLDR: I can now run S-Boot and TEEGRIS TrustZone TAs in QEMU but too lazy to find bugs.

It's been a while since I had a Samsung phone, my last was Galaxy S2.

It's also been a while since I last looked into bootloader binaries.

Last year I got an Exynos S9 model, mostly because I was impressed by its

CPU benchmark scores and wanted to run my own code to measure it.

This year I got some spare time but since S10 came out and a lot of people

have already looked at S9 software, I've decided to start reverse engineering

the software from S10.

S-Boot bootloader image layout.

github gist

- 0x0: probably EPBL (early primitive bootloader) with some USB support

- 0x13C00: ACPM (Access Control and Power Management?)

- 0x27800: some PM-related code

- 0x4CC00: some tables with PM parameters

- ... -> either charger mode code or PMIC firmware

- 0xA4000: BL2, the actual s-boot

- 0x19E000: TEEGRIS SPKG (CSMC)

- 0x19E02B: TEEGRIS SPKG ELF start (cut from here to load into the dissasembler). This probably stands for "Crypto SMC" or "Checkpoint SMC". This handles some SMC calls from the bootloader as part of Secure Boot for Linux.

- 0x1ACE00: TEEGRIS SPKG (FP_CSMC)

- 0x1ACE2B: TEEGRIS FP_CSMC (ELF header). My guess is that it's related to the Fingerprint sensor because all it does is set some registers in the GPIO block and USI block (whatever it is).

- 0x264000: TEEGRIS kernel, relocate to 0xfffffffff0000000 to resolve relocations

- 0x29e000: EL1 VBAR for TEEGRIS kernel. fffffffff0041630: syscall table, first entry is zero.

- 0x2D4000: startup_loader package

- 0x2D4028: startup_loader ELF start. This one's invoked by S-Boot to read the TEEGRIS kernel either from Linux kernel via shared memory or from the LZ4 archive compiled into S-Boot.

There's also one encrypted region containing ARM Trusted Firmware which is EL3 monitor code. It's right after the bunch of Rijndael substitution box constants.

Running S-Boot in QEMU.

I've long wanted to run S-Boot in QEMU for reverse engineering it.

I think I've mentioned this idea to my colleague Fred 2 years ago which kind of motivated him to write this great post about Exynos4210 early bootloader in SROM.

Check out his blog if you're interested in Samsung, btw.

https://fredericb.info/2018/03/emulating-exynos-4210-bootrom-in-qemu.html

Long story short, with a bit of hacks to emulate some MMIO peripherals I've prepared the patch for QEMU to run S-Boot from Exynos9820.

QEMU Support for Exynos9820 S-Boot

SCTLR_EL3 register

According to ARM ARM, top half of SCTLR is Undefined.

Samsung reused them to store the base address for the S-Boot bootloader.

When running in EL3, part of SCTLR is used when computing the value to write to VBAR registers which point to the Exception Table.

I initially attempted running S-Boot in EL3 but it checks EL at runtime and I believe it's actually running at EL1 but the binary supports EL1, EL2 and EL3.

Re-enabling debugging prints

Turns out, early in the boot process the bootloader disables most of the debugging logging.

I've prepared the GDB script to work around that.

gdbscript

set *(int*)0x8f16403c = 0

UART

https://github.com/astarasikov/qemu/blob/exynos9820/hw/arm/virt.c#L1900

As usual (WM5 blog [http://allsoftwaresucks.blogspot.com/2016/10/running-without-arm-and-leg-windows.html]), we can solve it by making the MMIO Read request return different data on subsequent reads.

We simply invert the value in cache on each invokation.

Using this trick we can bypass busy loops which wait for some bits to be set or cleared.

In fact, emulating two UART registers, status and TX, is enough to get debugging output from the bootloader.

Peripherals

We can identify some peripherals either by looking up their addresses in Linux Device Tree files

or by analysing what is done by the code that accesses them.

For example, we can easily identify Timer registers.

EL3 Monitor emulation.

S-Boot calls into the Monitor code (ARM Trusted Firmware) to do some crypto and EFUSE-related operations.

These calls have argument numbers starting with a lot of FFFFFF.

It was necessary to enable the "PSCI conduit" in QEMU which intercepts some SMC calls and add a simple

handler to allow S-Boot to properly start without crashing.

arm_is_psci_call

if ((param & 0xfffff000) == 0xfffff000) {

//Exynos SROM

return true;

Putting all the pieces together: running it.

./aarch64-softmmu/qemu-system-aarch64 -m 2048 -M virt -serial stdio -bios ~/Downloads/sw/pda/s10/BL/sboot_bl2.bin -s -S 2>/dev/null

At this point, we're not emulating most peripherals like I2C, PMIC, USB.

However, the bootloader gets to the point where memory allocator and printing subsystem is initialized which should be enough

to fuzz-test some parsers if we hook UFS/MMC access functions.

General approach to reverse-engineering

Samsung leaves a lot of debugging prints in their binaries.

Even in the RKP hypervisor, although most strings are obfuscated by getting replaced with their hashes,

some strings in the exception handler are not obfuscated at all.

With this knowledge, it's easy to identify the logging function, snprintf

and then strcpy, memcpy. Memcpy and strcpy are often near malloc and free.

Knowing this functions it's trivial to reverse-engineer the rest.

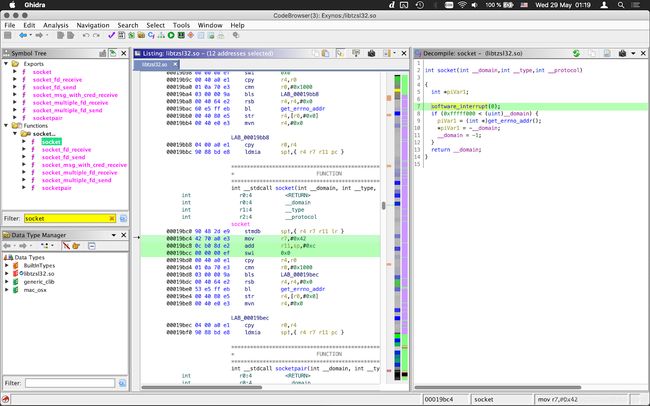

TEEGRIS intro

In the Exynos version of Galaxy S10, Samsung have replaced

the TrustZone OS from MobiCore with their solution called TEEGRIS.

As we've seen before, TEEGRIS kernel and loader are located inside

the BL image along with S-Boot.

Userspace portion - dynamic libraries and TAs (Trusted Applications)

reside in two locations:

- System partition ("/system/tee"):

- A TAR-like archive linked into the Linux Kernel

Here is what we can find:

- 00000000-0000-0000-0000-4b45594d5354 (notice how 4b 45 49 4d 53 54 are ASCII codes for "KEYMST" (Key Master))

- 00000000-0000-0000-0000-564c544b5052 VLTKPR (Vault Keeper)

- 00000005-0005-0005-0505-050505050505 - TSS (TEE Shared Memory Server?)

- 00000007-0007-0007-0707-070707070707 - ACSD (Access Control and Signing Driver?) basically the loader for TAs with a built-in X.509 parser

I wrote a Python script to unpack the (uncompressed) TZAR files.

https://gist.github.com/astarasikov/f47cb7f46b5193872f376fa0ea842e4b#file-unpack_startup_tzar-py

After unpacking the file "startup.tzar" from S10 kernel tree (LINK)

we can see that it contains a bunch of libraries as well as two TEE applications

which can be identified by their file names resembling GUIDs.

Security mechanisms

- Boot Time: TEEGRIS kernel and startup_loader reside in the same partition as S-Boot so their integrity should be checked by the early bootloader (in SROM).

- Run Time: TrustZone applets (TAs) are authenticated using either built-in hashes or X.509 certificates.

- Trustlets and TEEGRIS kernel has stack cookies and they are randomized.

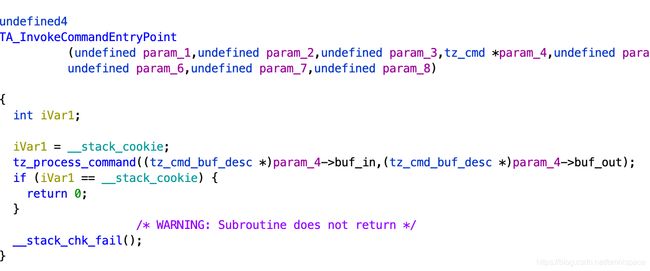

All TAs are ELF files which export the symbol "TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint" which

is where requests from Non-Secure EL1 (and other Secure EL0 TAs) are processed.

Additionally, some extra TZ applets can be found in the "system" partition.

Indentifying TEEGRIS syscalls

Attempt 1 (stupid)

Look for the syscall number and a compare instruction.

For example, for the "recv" syscall, let's search for 0x38, filter results by "cmp".

No Luck. Ok, it's probably using a jump table or a function pointer array instead.

Attempt 2

Let's locate AArch64 exception table and go from there.

We can find it by a bunch of NOPs (1f 20 03 d5) immediately after a block of zero-filled memory.

We can then find the actual exception handler for EL0 by knowing the offset from the ARM ARM.

https://developer.arm.com/docs/100933/latest/aarch64-exception-vector-table

P.S.

In fact, the code which launches "startup_loader" sets VBAR_EL1 to the same

address which we've identified before.

Syscalls

Luckily for us, Samsung put wrappers for each syscall into the library called "Libtzsl.so"

so we can easily recover the syscall names from the index in the table.

TEEGRIS IPC

Curiously, Samsung chose to implement two popular POSIX APIs to communicate

between TAs as well between TAs and REE (Linux): "epoll" and "sendmsg/recvmsg".

Peripherals such as I2C and RPMB are of course handled by file paths with magic

names, like on most UNIX-like kernels.

List of (most) TEEGRIS syscalls

https://github.com/astarasikov/qemu/blob/teegris_usermode/linux-user/syscall.c#L11590

TEEGRIS emulator

Since I'm better at reverse engineering than at exploitation

and I like writing emulators but hate code review, I decided to

find a way to run TAs on the Linux laptop instead of the actual

device.

Besides doing full-system emulation, QEMU supports the "user" target.

In this case it loads the target ELF binary into memory and translates

instructions to the host architecture, but instead of blindly passing

syscall arguments to real syscalls it can patch them and do any kind of

emulation.

Here are the changes that I needed to make in order to run TEEGRIS binaries instead of Linux ones:

- ELF Entrypoint: setup AUXVALs in a specific order that "bin/libtzld.so" expects

- Slightly different ABI: register X7 is used for the syscall number for both ARM32 and ARM64

- https://github.com/astarasikov/qemu/blob/teegris_usermode/linux-user/syscall.c#L11785

- TLS handling (QEMU bug?)

Current Status.

- Boots TAs, both 32-bit and 64-bit

- Currently does not support launching TAs from TAs (thread_create)

- Currently only invalid command handler is reached. Need to improve

- recvmsg or patch the library code as a workaround.

- But overall it should be possible to build a fuzzer for TAs in less than a week of work now.

Here's one idea: now that we know we've emulated enough of syscalls

for a TA to boot and start message processing, we can just override the

return address and arguments for one of the syscalls which are invoked

in the message processing loop and redirect the execution directly

to TA_InvokeCommandEntryPoint.

For this proof of concept I've manually identified the entry point address

and adjusted it according to the ELF base load address and QEMU-specific load

offset. Of course it would be better to automate this part so that TA loader

is more generic but as every software engineer knows, those who write

good code get scooped by those who don't.

This kind of works in that we're getting messages from inside the TA: check the full log at https://pastebin.com/sVtWk5CD and search for "keymaster [ERR]".

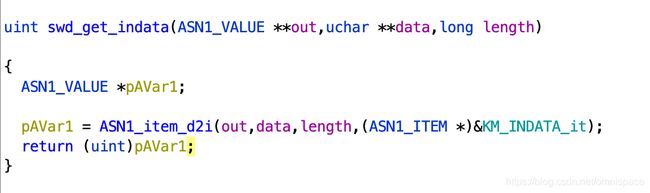

However, it fails early when validating the message contents.

We need to generate the correct ASN.1 payload which should be doable

since ASN.1 grammar templates are compiled into the binary.

Ideas for future research

- Hook malloc/free and some other functions and invoke native system C library calls.

- Hook QEMU JIT (TCG) or interpreter to check memory accesses against ASAN shadow memory. This way we can enable Address Sanitizer for binary blobs, similarly to how Valgrind does memory debugging. Since QEMU Usermode runs TAs in the same address space as itself, we can use ASAN allocator or libdislocator to detect OOB memory access. Unicorn is kind of hard to use because for this because it does not allow to easily set up MMIO traps, it only allows to register chunks of normal memory.

- Finish reverse-engineering ASN.1 format for Keymaster and fuzz this TA.

- Run TEEGRIS kernel in QEMU as well to fuzz syscalls.

- A Ghidra script to rename functions according to the debug strings passed to invokations of print callees

- Look at the ring buffer implementation in the shared memory.

Running TEEGRIS Emulator

export TEE_CMD=777

qemu/teegris$ ../arm-linux-user/qemu-arm -z fuzz_keymaster/in/test0.bin -cpu max ./00000000-0000-0000-0000-4b45594d5354.elf

Debugging panics with GDB

- https://github.com/astarasikov/qemu/blob/teegris_usermode/linux-user/syscall.c#L11929

- Uncomment the code in the "panic" syscall which sets PC to 0x41414141 so that the exception is delivered to GDB.

- Add -g 1234 to qemu-arm arguments to listen for GDB.

- Run the GDB script in root folder: "qemu$ arm-none-eabi-gdb -x gdbinit"

Related Projects

Post from Daniel Komaromy on reverse-engineering Galaxy S8 which mostly focuses on the other part of the picture: getting from Linux into Secure EL0.

- https://medium.com/taszksec/unbox-your-phone-part-i-331bbf44c30c

Blog from Blue Frost Security on reverse-engineering S9 TrustZone. The OS kernel is different but actual TAs are the same.

- https://labs.bluefrostsecurity.de/blog/2019/05/27/tee-exploitation-on-samsung-exynos-devices-introduction/

- https://labs.bluefrostsecurity.de/files/TEE.pdf