回顾社交游戏公司Zynga创业史

原帖: http://gamerboom.com/archives/44239

作者:Dean Takahashi

在短短的5年时间里,Zynga便在电子游戏领域里掀起了巨大的热潮。即将迎来重要的IPO,这家公司已经成功叙写了游戏历史上辉煌的一篇。

但是,Zynga的成功从来都不是预料之中的结果。事实上,早前大多数游戏产业的资深人士甚至不把它当成一家真正的游戏公司。Zynga创始人Mark Pincus曾经4次创业,但是对于游戏产业他却没有任何经验,并且他之前创办的公司也都不算是大公司。所以,他看起来是最不像能够创造出游戏产业巨头的企业家。

而现在,Pincus作为该公司最大的股东,已经是身价不可估量的亿万富翁了。Zynga的数十亿美元IPO以及89亿美元的估值都让这次募股活动无可厚非地成为游戏历史上的一个大事纪,使Zynga步入EA、动视等游戏巨头的行列。

Pincus这位游戏新手幻想着成为游戏产业主导者的同时,他也在创造着可接近大众的社交游戏,正是这种游戏为他创造了成功的可能性。度过重重困难,Zynga已经在社交游戏淘金热潮中打败了许多游戏巨头。从2009年开始,Zynga的游戏已经连续多年蝉联Facebook游戏榜首。截至今天,他在Facebook上仍有5款大受欢迎的游戏。

而单凭Pincus自己的能力是不可能做到这些的。在这期间,他很幸运地遇到了游戏元老Bing Gordon并接受了他的帮助。前Facebook首席运营官Owen Van Natta也在这期间给予了Pincus巨大的帮助。资深游戏设计者,如Mark Skaggs和Brian Reynolds也不断创造出有创意且吸引人的好游戏,帮助该公司洗清其早期因为制作仿制游戏和垃圾邮件游戏落下的坏名声。Zynga能有今天如此杰出的成绩都离不开这些人的帮助,而如此雄雄气势导致其竞争对手,如Playfish和Playdom不得不另辟蹊径,尽快寻找其它能够赚钱的出口。

mark-pincus(from venturebeat)

2007年建立以来,Zynga已经创造了超过15亿美元的收益,这对一家新兴公司来说确实是件了不起的成绩。现在,该公司仍将争取占领虚拟商品市场收益的多数份额,该市场产值已达90亿美元,Zynga预期这一数据今后五年还将翻三倍。

如今,Zynga的目标是成为能与搜索界的谷歌,购物界的亚马逊以及最大分享平台Facebook平起平坐的游戏界之最。Zynga很幸运,它在初始阶段并未拥有多少游戏经验,但在整个发展生涯中,却能不断地向世人证实自己成为一家真正游戏公司的潜质。

本文将从Zynga的早期发展阶段开始说起。Zynga的故事并不只是关于该公司的创办者,还应该包含他身边的各种角色,甚至是激励他争取成功的对手,以及其所面临的各种挑战。我们将从三个方面去讲述Zynga能够获得如此成就的原因以及其中所面临的挫折。

平凡的出生

Pincus在2009年春天的Startup Berkeley上发表了关于创办企业的演讲时曾经说过:“在我成为一名企业家之前我尝试过各种职业。其中更是屡受挫折。就像你想成为一名职业运动员之前,必须先参加少年联盟。在你能够真正应对失败之前你可能会经历无数次的失败……在众多工作中,我被解雇了多次,也有些是我主动向老板提出请辞。”

Pincus开玩笑地说道,最后留给他的选择就只剩下创业了。他曾经读过George Gilder(游戏邦注:当今美国著名未来学家、经济学家,被称为“数字时代的三大思想家之一”)的著作《微观宇宙》,并因此对于这个受技术主导的经济学世界充满兴趣。因此让他萌生了接触新媒体的想法。1995年,携着25万美元的贷款他来到了硅谷,创办了FreeLoader这家网络推动公司。运营7个月后,他将FreeLoader卖给Individual赚得了3800万美元,可以说这是一家见证了Web 1.0时代开端的网络公司。

那时候,其他以数千万美元甚至是上亿价格出售的科技公司并不鲜见,Pincus出售这家公司算不上是什么重磅交易。但不管怎样,这第一家初创企业的成功让Pincus在硅谷的网络浪潮中获得了立足点。随后他便与Cadir Lee和Scott Dale共同创办了Support.com(也就是后来的SupportSoft)这家以提供自动化软件维护和服务的公司。该公司在2000年7月上市。

带着充足的资金,Pincus于2000年1月创办了Tank Hill。但是那时正好碰上了互联网泡沫,所以他和合作者便不得不最终关掉这家公司,并且直到9个月后才弥补了其中的亏损。2003年,37岁的Pincus开办了Tribe.net这家最早的社家网站之一。Pincus将其称之为“Craigslist与Friendster的合体。”但是最终这个网站也未能为其带来较大回报。2005年,在该公司的董事会抛弃了Pincus后,他最终离开了这家公司。但在2006年,他再次从投资者的手上夺回了Tribe.net,并将其资产出售给思科。那时候,Tribe.net只有8名员工,思科在2007年3月完成了这笔收购交易。

他与好友Reid Hoffman(付费平台PayPal的核心成员以及Linkedin的创办者)合作,以70万美元从Sixdegrees手中购买了社交网络的专利权。随后他们便投资于当时还没什么名气的Facebook这家最终开启了Web 2.0潮流,并最先利用动态网络而推动用户在网上进行交流的公司。如此Pincus便与Facebook的创始人Mark Zuckerberg建立起了密切关系,而为他今后所掀起的“社交游戏革命”创造了有利条件。

按照官方的说法,Pincus总共创办了4家公司,但是根据他自己的描述,他已经遭遇过15至20个项目的失败了。但是Pincus确实一个非常成功的天使投资者。他投资的公司包括Napster, eGroups, Technorati, Socialtext, Friendster, Ireit, Nanosolar, Merlin, Naseeb, EZboard, Advent Solar, Xoom以及Facebook。显然,我们在这个列表中却看不到任何游戏公司的身影。

下对了赌注

在创办Zynga之前,Pincus表示自己曾经遭遇了3次惨痛的失败,其中便包括Tribe.net。还有一次失败是来自于名为Tag Sense的广告公司。随后,他总结道:“不要因为有了用户或者赞助者就想着创办公司。如果这只是你的边际想法,你便很难获得好结果。”

Pincus表示,Tag Sense的迅速失败使得他不得不寻找更好的机遇,而2007年5月份,当Facebook开启了应用程序界面并邀请其他公司创造基于该社交网络的应用程序以打败MySpace时,Pincus看到了希望。如此便为Facebook争取到更多用户和开发者,形成了一种良性循环。而Pincus也决定步入这股潮流中。

在Presidio Media(Pincus在2007年4月创办的公司)推动之下,Pincus也赶上了Facebook发展大潮。

在2009年的一次访问中Pincus说道:“在运营Tribe期间,我发现自己真正想做的是关于游戏的事情。我总是说社交游戏就像是一场很棒的鸡尾酒会:一开始你会很开心能够见到好朋友,但是对于鸡尾酒会来说,最大的特色便

是没有太大关联度的交际圈。你也会见到一些从未见过的陌生人,或者好友的好友等等。而我所想的,也是你能够做到的便是,一旦你带来了自己的好友,并与其他人的好友聚在一起时,你们便可以一起玩游戏了。我一直非常热衷于玩游戏,但是我却很少有时间与好友们聚在一个地方玩游戏。所以我认为先将好友聚在一起然后再引入游戏是个不错的主意。

2007年7月,Pincus将其新公司重新命名为Zynga(与其斗牛犬同名)。Zynga的首个总部位于旧金山Potrero Hill附近的Chip Factory。

根据自己以往的经验,Pincus认为:“命运是掌握在自己手中。我们总是在谱写着自己的故事,即我们是如何获得成功如何争取到风险投资以及如何创建自己的公司等。以及后来这些成功是如何慢慢远离我们并最终抛弃我们等。这也许是任何人都可能在硅谷所遭遇到的悲剧。而你之所以能够创建一家公司是因为你懂得如何控制这些命运。”他说道,如果自己能够控制公司及其命运,他便达到了一半的目标了。而带着这种想法,他独自创办了Zynga。

Zynga早期的团队成员包括Eric Schiermeyer, Michael Luxton, Justin Waldron, Kyle Stewart, Scott Dale, Steve Schoettler, Kevin Hagan, and Andrew Trader。Pincus对这些成员们的要求很高,但那是因为他真心希望能够创建一家非常优秀的公司。

Zynga的首次成功来自于MySpace,这个平台的社交游戏公司主要通过广告实现收益。虽然Zynga最初的收益来自MySpace,但是Pincus预见到Facebook能够为他们未来的发展提供更广阔的平台。可以说这是一次很明智的赌注,让Zynga能够抓住Facebook这个滑板,朝着更加明亮的未来冲刺着。

当他有了这些想法后,他便时刻提醒自己应该尽所能且快速地验证它们。

Zynga于2007年9月在Facebook发行了第一款游戏。这是一款免费的扑克类社交游戏,之所以选择这类型游戏是因为它不仅简单,而且是一种非常普遍的游戏,好友们无论相距多远都能够一起享受扑克游戏的乐趣。这款游戏的发行重新掀起了扑克游戏的热潮(从2003年以来)。第一款Facebook游戏的成功为Zynga带来了巨大的利润。

Pincus在2009年接受美国知名科技博客网站VentureBeat的访问时说道:“我们是第一家看准了社交游戏机遇的公司,并在2007年7月携带着我们的扑克游戏去追逐这一机遇。当其他人关注于病毒式应用或者病毒式传播内容时,我们只是单纯地瞄准游戏机遇。那时候的我们真心认为这是一种真正且持续的收入来源,所以我们便义无反顾地首先淌进这股潮流中。”

在Zynga的游戏出现之前,免费游戏一直被当成是一些低质量的共享软件。但是现在,它们却是深受众人喜欢的游戏。扑克游戏只能暂时获得一些用户,但是在一开始它们只能够从广告中获得收益。最后,在2008年3月,Zynga便决定通过“引导性销售”贩卖扑克筹码,即让玩家在参加相关广告赞助活动中获取这些筹码。

Pincus在Berkeley发表的演讲中说道“之前我们采取的是大家所熟知的立刻获益的方法。”而在Zynga的第一款Facebook游戏《Texas Hold ‘Em Poker》中他们通过使用扑克筹码间接获益,即让玩家下载了维基工具便能够获得该筹码。

在2008年中旬,Zynga发行了第二款Facebook游戏《Mafia Wars》,以及随后收购的《YoVille》。《Mafia Wars》同时出现在Facebook和MySpace上,因为那时候Zynga还不能判别哪个网站能够最终脱颖而出。

在发行游戏的过程中,Zynga慢慢摸索出了一些独到的观点,并最终成为他们开发游戏的理念。他们认为不论在哪里以及不论何时,游戏都应该具有易用性,社交性和免费特点。游戏必须以数据为设计指导,游戏本身必须是优秀的。说起来这些都是游戏必须获得的崇高目标,但是在这个产业中却甚少有人领悟并尝试实现这一点。

Pincus希望自己能够在寻求风险资本家帮助之前创造出一个真正出色的公司。那时候Zynga刚刚完成了首次融资,在2007年他们只获得69.3万美元的收益,但其用户增长迅速,而且利润已经很可观。结果便是,Pincus因此而获得一些特殊待遇,如掌握比普通股多10倍的投票权,并保持自己在董事会中的权力。

他已经和许多投资者交好,在2008年1月15日宣布已经通过Union Square Ventures, Foundry Group, Avalon Ventures, Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel等天使投资者融资5百万美元的资金。

获得了新的资金,Zynga便能够更快速地在Facebook这块“乐土”上进行开拓了。Facebook不断调整平台政策,而应用开发者便不得不针对性地更改自己的应用。Pincus称其为“有机开发”,在这个过程中公司的内部开发者不得不时刻关注Facebook的动向,每隔90天左右就要修改自己的产品。

这是一个结合了设计师的直觉和反馈数据,深受参数影响的行业。这使游戏项目能够快速迭代,获取用户,实现留存率与盈利性。这也正是Zynga领先于其他公司的原因:他们了解自己的用户想要什么,并且能够有针对性地快速修改游戏,有时候只要一夜便能为用户提供其所需的内容。Zynga开始验证各种游戏理念。对于Web 2.0公司来说这种做法很平常,但是其他众多游戏公司却没有做到这一点。

关于Zynga深受Facebook政策的影响,这种说法却是个不争的事实。

Pincus开玩笑地说道:“始终围绕着Facebook转悠是不是让我们觉得很苦恼?”“2007年当我们作为一家专门制作Facebook应用的公司时,所有人都在嘲笑我们。那时候我们的生死全都取决于Facebook所作出的任何改变。”

数据也是游戏设计者的天敌。如果一款游戏不会成功,Pincus就会豪不犹豫地取消这个项目。他可以投入3百万美元开发出一款不知名的角色扮演游戏,但如果在游戏发行时并不能获得广泛传播,Pincus便会叫停这个项目。

Pincus总是能够果断干脆地处决那些没有市场的游戏。

《Mafia Wars》和《Zynga Poker》取得的好成绩推动了Zynga的快速发展,并帮助他赚得了一大笔利润。而此时的Facebook也处于不断进步状态。

在那时候,发展速度非常关键。但是并非所有人都能够意识到这一点,所以有较高觉悟性的Zynga便毫无悬念地奔走在竞争跑道的最前方,赚取大量的收益。当时只要你知道如何利用社交游戏赚钱并快速执行这一理念,无论后来是否会有巨头公司介入,都能够率先在市场站稳脚跟。

所以在首次融资的几个月后,Zynga便又迅速募集了更大的一笔资金。

在2008年7月,风险投资公司Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers向Zynga投入2900万美元的消息引起世界的关注。Bing Gordon,EA前创意总监及现在Kleiner合伙人加入了Zynga的董事会。Mark Pincus真心欢迎这位大牌顾问的加入。

那时候,对于游戏初创公司来说越多资金越有利,但是却很少有游戏公司能够募集到如此高的数额。而Zynga的如此机遇意味着他们可以投入更多的资本去开发下一款大游戏。这是很多竞争者所望尘莫及的,也是为何他们远远落后于Zynga的重要原因。

后来,Pincus总结道,避免失败的一大教训便是待在那些让你有所收获的人群之中。Gordon便是这种良师益友。Pincus拥有Web 2.0的经验,而Gordon比之更了解游戏,他能够让Pincus接触到游戏产业中更多有潜质的人才,而吸引他们到Zynga创造出更多优秀的游戏。如来自EA的资深游戏设计师Mark Skaggs,他在2008年11月以游戏主管的身份加入了Zynga,他将帮助该公司创造出更多更成功的游戏。

Gordon在2010年秋天接受VentureBeat的采访时以Robert Duvall在电影《教父》中的角色为例进行说明:“我只是一个参谋。比起Robert Duvall,我甚至更像是一名招聘人员。但是我非常重视Mark Pincus这个有眼力的合作者。他很巧妙地将网络,游戏和社交结合在一起。这是前所未有的伟大创举。”

Gordon频繁现身于Zynga公司,不断地给予其他员工各种建议,并为该公司带来更多有帮助的人才。

招贤纳士

随着Zynga的扩张,该公司开始能够广泛吸收业内杰出英才,这部分是因为经济萧条令众多掌机游戏工作室走向消亡。Gordon加入Zynga董事会及时常现身公司有效提高其知名度。

Gordon清楚Zynga的声誉状况,他极力控制这所带来的负面影响。据《SF Weekly》所获文件资料显示,Gordon向其在克莱纳·珀金斯的合伙人发送秘密备忘录。

内容是:“Pincus现在需要几位得力助手使他摆脱事必躬亲的状态。”Gordon暗示自己和另一高管如今在公司扮演重要角色,能够左右平卡斯的看法。“为缓解马克的压力,在公司估值1亿美元的时候,Zynga聘请身价10亿美元的COO。”备忘录还警告说,Zynga过度依赖Facebook。

但Pincus维持的时间超乎大家的想象(游戏邦注:指公司的运作)。他通过随时留心杰出英才做到这点。他没有干坐着等待其他游戏开发者投奔他。

有时,Pincus会遇到技术专家,这时他会说服他们转投游戏开发。25岁的卡内基梅隆大学毕业生Justin Cinicolo(他有几年工作经验)就决定投奔Zynga,因为他的室友也在那任职,每天回来都笑脸盈盈。Cinicolo很早就加入公司,非常着迷于公司的快节奏和文化氛围,于是他又邀请若干他在卡内基梅隆的好友加入公司。

Cinicolo发现,Zynga极力践行自己的核心价值观。公司告诉员工“要制作自己和好友乐于体验的作品”,“Zynga是精英管理的社会”,“努力变成CEO,掌握自己的成果”,“顺应Zynga的节奏”,“将Zynga置于首位,决策要旨在获得更突出的成就”以及“保持创造性”。有些人也许会觉得有些可笑,但Cinicolo却从中看到真理。

据Pincus回忆,在自己的第二家公司里,他将传单放至墙上,将所有人的名字都写在上面。Pincus表示,“每周末,所有人都需要写说自己是XXX的CEO,所写内容需要富有意义。大家这很喜欢这个提议,完全无法隐藏自己。”

《黑手党战争》发行后,Cinicolo被任命为游戏的制作人。他的职责是确保游戏持续发展,超越所有竞争作品。

分析这款游戏时,他需要依靠Cadir Lee(游戏邦注:他同Pincus联合创建两家其他公司,于2008年11月加入Zynga,当时公司有职员100人)制作的工具。此时,Lee的职责就是创建整个游戏行业的最大数据库。

Lee的首份工作是创建分析仪表板,从系列数据切换至用户界面,向Cinicolo之类的制作人呈现游戏的所有相关信息。他们能够进行A/B测试,看看玩家更喜欢粉色信息,还是蓝色信息。当结果出现时,玩家就能够判断哪个效果更好,各公司就能够迅速从中吸收相关经验教训。

Lee曾在2010年秋的访谈中表示,“我们令公司从毫无分析法到享有如今的竞争性微分器。我们握有众多基础设备、分析法及统计人员。这是Zynga的生命线。”

社交游戏开发公司Cmune的首席执行官Benjamin Joffe表示,Zynga已将分析法变成一门科学,基于“运作更多可行内容”原则运行。

这是令传统游戏开发者心生厌恶的另一方面内容。他们希望通过直觉和技能,而非大众投票设计自己的作品。但有些人确看到了其中的价值。通常,设计师会在某款掌机游戏中投入2-5年时间,然后等到发行日才能知晓玩家是否喜欢这款游戏。而在Zynga,设计师制作的代码,玩家隔天就能够看到。用户反馈非常即时。

通过分析工具,Cinicolo能够更轻松地推广《黑手党战争》。游戏发行4个月后就获得10万用户。Cinicolo的目标是将此数据发展至100万。当他实现此目标时,其上司Eric Shiermeyer要求他争取200万。第二年,《黑手党战争》的发展非常惊人,2009年和2010年的营收分别达到3200万和1.61亿美元。目前《黑手党战争》依然拥有600万MAU。

Cinicolo在2010年秋的访谈中表示,“我凭借混杂团队游走于众多项目之间。我浑身充满活力。若出现漏洞,我们会立即进行修复。”

根据项目的不同,Cinicolo会每月或每周同Pincus碰面,征求老板的意见,看看如何让游戏变得更好。团队成员会在吃饭和小酌时谈论下步进展。到2010年,他们开始涉足手机游戏领域。

Cinicolo表示,“Pincus就像个合作伙伴,一点儿也不像老板。他和我们共同工作。从某些方面看,他有所改变。他变得更冷静,还是和以前一样精力充沛,充满激情。但他变得更愿意涉猎手机平台,我们知道要在此平台取得类似于网络平台的成就还要耗费很多时日。”

2010年秋,Cinicolo(游戏邦注:此时他28岁)开始负责许多重要手机项目,担任手机业务总经理。

2008年末,Maestri结束同SGN的官司,获得《Mob Wars》的所有权。2009年9月,他同Zynga顺利和解,Zynga同意赔偿他700-900万美元。此时,Zynga陷入同Playdom的纠纷,Zynga控诉Playdom聘请公司前雇员,意图抄袭他们的作品,盗取他们的“秘诀”制作热门游戏。

《FarmVille》的诞生

2009年春,小型开发公司Slashkey推出游戏《Farm Town》。这是款简单的农场游戏,和中国的传统农场游戏或掌机平台的《牧场物语》游戏大同小异。游戏让玩家能够模拟农场生活和发展。仅凭病毒式口碑传播,游戏就得到迅速传播,每天增加30万用户。在短短几个月时间内,游戏就在Facebook上获得1400多万注册用户。

《FarmVille》显然是款仿制作品,但游戏的起源已经无法考证。现于Zynga任职的前EA设计师Mark Skaggs称这款新游戏的构思来自Bing Gordon。有天他问道:“我们为什么不制作农场游戏?”这正与Pincus心中想法一拍即合。

Skaggs是Zynga早期非常重要的设计师。他曾负责监管EA的众多PC游戏,这些游戏共售出1600万份,从《命令与征服之将军》到《魔戒:中土大战》。他在EA任职7年,从EA收购Westwood Studios开始。2005年他离开EA同他人联合创建Trilogy Studios,他们曾制作过一款大型多人在线游戏,但最终未能成功。所以Bing Gordon建议他加入Zynga。他很早就进入Zynga,因此给公司的游戏设计方式带来很大影响。

遗憾的是,Zynga没有完整的团队。Skaggs只好将目光瞄准外面。Zynga于是商谈收购MyMiniLife,此工作室有若干雇员及一个游戏引擎,这能够运用到农场游戏。MyMiniLife团队发展至9个人,他们花费5周时间完成任务。其中有些工作早在Zynga收购MyMiniLife(游戏邦注:此工作室由Sizhao Yang运作)前就已完成。

MyMiniLife成立于2007年,是个拥有400万用户的社交网络。但MyMiniLife极力想要留住自己的用户,Slide的Max Levchin首次提出收购请求,然后是Zynga、Hi5和Challenge Games。Zyng宴请团队成员,不断提高报价。Pincus在此交易中投入较多时间,最终于2009年6月5日达成协议,但收购价码没有向外公布。当时Pincus表现得异常果断。他凭借自己的直觉,促使团队找到正确方向,最终达成交易。

MyMiniLife创建能够承载众多用户的稳定平台。若没有此平台,公司的发展计划就会成为问题。

其制作团队发展很快,于是他们开始模拟Zynga《YoVille》中的虚拟角色。妈妈们通过Facebook监督孩子的活动或同老朋友联系,这是他们的主要目标。

2009年6月19日,Zynga推出自己的首款《Farm Town》克隆作品《FarmVille》。游戏的制作周期只有5周,但其发展速度却达到空前规模。与其竞争作品不同,Zynga在社交网络广告中投入大笔资金。短短两周内,Zynga《FarmVille》就获得500万用户,平卡斯转移其他项目的资源,用于支持《FarmVille》的发展。

此时《Farm Town》遇到发展瓶颈,而《FarmVille》却在4-5天内就获得100万用户。该游戏当时已收获众多用户,该公司开始使用亚马逊的外部计算机服务(亚马逊Web Services部门外租公司核心电子商务不需要的数据平台)。

其运算容量令Zynga收获很多。Zynga首席技术官Cadir Lee曾在2010年秋的访谈中表示,Zynga能够挖掘自己的数据,因为它是家网络公司。

他表示,“我们在有内容进展的5分钟内就能够收获数据。参数和数据观察是文化的组成部分。网络公司进行很多分析工作。在此虚拟世界中,玩家追踪所有进展情况,例如有多少块优质草莓田地。”

相比Slashkey之类的小公司,Zynga在快速发展方面所做的准备要多得多。

Lee表示,“我们替《FarmVille》解决众多技术问题。有段时间,我们的服务器几乎濒临爆炸边缘,于是我们推出新技术,这给予我们更多发展空间。我们掌握能够扩充的内容,后来我们就真正转变创建游戏的方式。我们发现真正的关键不在于硬件,而是应用架构。我们需要充分利用亚马逊的优势。”

传统游戏设计师鄙视Zynga“游戏”

乔治亚理工学院教授Ian Bogost非常反感《FarmVille》,觉得游戏缺乏玩法,于是推出效仿作品《Cow Clicker》(游戏邦注:在此玩家的所有操作就是点击乳牛)。

到2009年7月,全世界都开始明白Zynga为何能够快速发展。2009年7月31日,据comScore报道,Zynga成为全美排名第一的在线游戏运营商,超越Yahoo Games,MAU达4400万。Pincus称关于Zynga在2009年营收将突破1亿美元的预测实际上还非常“保守”。

免费商业模式开始出现。短短几个月内,《FarmVille》就变成全球最大的在线游戏,其中少量的付费用户足以让游戏获得丰厚营收。

Zynga的农场游戏融入的一个重要功能是“枯萎”机制,这会让玩家的庄稼逐步枯萎,这样若你没有快速收割,它们就会失去价值。这促使用户经常回访游戏;Zynga出售“复兴”道具帮助玩家挽回枯萎庄稼。这也是游戏能够获得如此丰厚收益的原因所在。

Pincus曾在2009年的访谈中表示:

看看《Farm Town》,这款游戏获得约300万DAU,然后就此打住。你得确保自己是家能够向用户提供支持的公司,能够处理欺骗和付费问题,所有这些元素都会迫使你做出决定,是否要双倍下注,投资长期项目。其管理难度会提高,你需要应对众多员工。从一开始,我们就知道自己希望变成一家长久的公司。我们无疑能够变成长久的公司。

2009年9月,Zynga发布《咖啡世界》,这是款餐馆建设游戏。这显然是是《Restaurant City》(游戏邦注:发行于2009年4月的Facebook游戏)的复制品。这款游戏由总经理Roy Sehgal负责,成为Zynga迄今发展最快的作品。Seghal曾在访谈中表示,Clubhouse Studio团队由25位制作人、产品经理、游戏设计师、美工和程序员组成。他们来自不同背景,不仅仅包括游戏领域,他们在这款游戏中投入5个月时间。并非所有人之前都有接触过游戏领域。

很快,Zynga的《咖啡世界》就获得2800万DAU,而《Restaurant City 》则只有1600万。这仿佛就是《FarmVille》vs《Farm Town》的翻版。

Zynga获得的收入比对手多,因此它能够进行大肆广告宣传。当然风险会越来越大。游戏每安装一次,RockYou之类的广告网络运营商就从中分成1美元。这意味着,只要RockYou说服用户试验游戏,开发商就要支付1美元。随着时间的推移,Facebook的广告成本开始提高,很多初创公司都无法继续维持。这令他们变得举步维艰,最后只有将公司出售给Zynga之类的竞争对手。

截至2009年秋,Pincus仿佛就是个预言者。在Web 2.0峰会上,他预测行业未来将基于“应用经济”。此时,Zynga拥有5000多万用户,其中包括2000万的《FarmVille》玩家,每天售出80万台虚拟拖拉机。这一切都发生在经济危机时期。而此金融危机却弱化了Zynga的所有竞争者。

三大巨头

Zynga逐渐赢得更多尊重。但在Zynga,真正的关键是员工能否胜任工作,快速前进。这也是为什么当游戏《FarmVille》问世时,Zynga能够紧握住机会。

在Zynga,Pincus总是试图保持态度谦虚和反应灵敏。他曾在访谈中称自己不喜欢关于公司的正面新闻报道,因为这会让他想起自己的“失败经历”。

随着《FarmVille》的急剧发展,很多投资者发现2009年是社交游戏的蓬勃发展阶段。掌机游戏和广告休闲网络游戏都在经济萧条期间慢慢冷却。进一步令世人意识到此发展趋势的是,2009年6月,EA第二重要角色John Pleasants辞去现有职位加入Playdom,担任公司CEO。当时EA有员工9000人,而Zynga只有65人。这令大家觉得如今社交游戏处于淘金热阶段。

Pleasant的离开逐渐变成某种趋势。大型公司的高管们想要抓住热门社交游戏公司的赚钱机会,趁机谋取利益。在Pleasants离开EA前后,Simon Jeffery也辞去世嘉美国总裁的职位,加盟iPhone游戏初创公司Ngmoco(游戏邦注:这家公司由前EA高管Neil Young创建),担任执行主管。竞赛正拉开序幕,谁都不想落后。

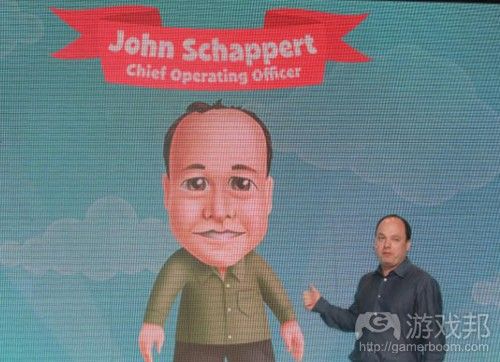

其中模式非常清晰,没有高层管理者愿意提及这点。但这些高管不是试着解决大型公司在过渡至数字阶段所遭遇的问题,而是直接加入数字市场,选择创建或加入iPhone或社交游戏公司。而此时,EA宣布Pleasants的COO职位已由重新归来的John Schappert取代。

Zynga促使免费模式和异步玩法(或是回合游戏,其中玩家轮流操作)的组合内容在社交网络上得以顺利运作,此平台的玩家通常每天只有几分钟的体验时间。回合游戏令玩家能够在自己方便的时候进行离线操作,同远方的好友进行社交互动。这是适合众多用户的模式,他们很多都未将自己当作玩家,因为他们没有时间进行游戏体验。

Inside Network当时曾预测,美国虚拟商品市场有望创收10亿美元。这些收入主要集中在3大社交游戏巨头:Zynga、Playdom和Playfish。Zynga凭借《FarmVille》遥遥领先,但若有公司推出一款轰动巨作,此排名将随时发生改变。

人人都能够制作Facebook游戏。但困难的是如何让作品在应用遍布的社交网络中脱颖而出。Facebook的主流游戏公司能够轻松向既有用户交叉推广自己的新作。掌机游戏发行商开始对此投以关注。但若未能以某款热门作品做铺垫,他们将举步维艰。EA于2009年秋推出《Spore Islands》(游戏邦注:基于PC热作的社交游戏),但游戏最终不尽人意。

迫于渴望加入新市场,大型游戏公司开始纷纷周旋于此市场。Schappert试图浇灭初创公司的激情。2009年,Schappert曾在某谈话中表示,社交游戏泡沫将越变越大,就好比几年前用于包装手机游戏和虚拟市场的大肆宣传。

他表示,2005年12月,EA同意以6.8亿美元收购Jamdat Mobile,此时正是手机游戏泡沫的巅峰时刻。风投资本家投资众多手机游戏初创公司,旨在期望能够获得同等收益,结果此高峰却逐步转移至虚拟世界,例如Second Life。

Schappert表示,“社交游戏吸引众多眼球。风投资本开始不断涌入。这能够持续下去,还是只是泡沫现象?社交游戏和手机游戏存在众多共同之处。那些称盒装游戏即将消失的人士,他们有些高估自己。”

Schappert并不否认社交和手机市场的存在。但他表示,2年内社交游戏将步入成熟阶段,淡出市场。Schappert表示,到那时,社交网络的热门作品将会变成那些熟悉的品牌,而非“我们闻所未闻的作品”。

从某种程度看,Schappert似乎在向Pincus传递某种信息。这样EA开始向Zyngaw伸出收购橄榄枝。Zynga要价10亿美元。就Zynga当时的营收来看(根据Zynga内部记录,公司2009年的收入是1.215亿美元,但还要扣除5280万美元的亏损),这是相当惊人的数字。Pincus一直都愿意将公司售出,只是价位非常惊人。此价格是否合理?Pincus的看法是,虚拟商品5年内将发展成巨大的市场,Zynga有望占据30%的市场份额。从这个角度来看,Zynga的价值高很多。与此同时,若有人愿意支付更高的价码,Pincus非常愿意出售公司。

mark-zuckerberg-mark-pincus(from businessinsider.com)

这种态度说明Pincus并不是只着眼于当前,而是放眼未来的更大可能性。他的情况和马克·扎克伯格很像,扎克伯格原本也有机会以10亿美元售出Facebook。据戴维·柯克帕特里克的著作《The Facebook Effect》所述,前Facebook执行总裁Owen Van Natta曾向扎克伯格提出收购要求。雅虎也伸出橄榄枝,想以10亿美元收购Facebook。扎克伯格回绝他的要求。据柯克帕特里克称,事实上,后来微软曾试图以150亿美元收购Facebook,扎克伯格也一口回绝。Pincus的情况和扎克伯格很相似,都是社交网络的天使投资人,他们的思维方式也很相近。

随后2009年11月9日,EA发生两件惊天动地的事情。据悉该公司将裁掉1500位员工,关闭众多工作室。裁员让游戏开发商有所感悟。M2 Research分析师Wanda Meloni发现,有60家游戏工作室在2009年7月-11月期间共裁员8450人。

该公司以3亿-4亿美元左右收购Playfish。Playfish被认为是颇具价值的公司,其始终推出原生作品,例如《谁最聪明》,拥有6000万MAU,但公司并没有进行大量广告宣传。Zynga如今的价值远胜过大家的预期,因为其规模超越Playfish。

EA也开始加入社交游戏领域。这发生在Schappert讲话后不久,其早前的讲话似乎旨在降低收购价码。在达成交易前,动视暴雪是EA的主要竞争对手。现在EA的头号竞争者是Zynga。EA首席执行官约翰·里奇蒂耶洛似乎打算在此最热门的游戏领域同自己的老同事Bing Gordon一较高下。

与Playdom对簿公堂

由于风险很大,Zynga不仅在市场上积极抗争,还在法庭上据理力争。2009年9月,就在公司结束同Maestri的《暴民战争》诉讼前,Zynga起诉Playdom盗窃商业秘密。很多业内人士都觉得此诉讼非常讽刺(游戏邦注:鉴于Zynga的抄袭传统)。但从Zynga的角度来看,抄袭无伤大雅。但偷窃文件、代码和游戏构思就有违常规。

此法律诉讼表明,业内竞争已变成一场白刃战。Zynga宣称公司前雇员(Raymond Holmes、David Rohrl、Martha Sapeta和Scott Siegel)离开公司时带走很多文件,其中包括“The Zynga Playbook”,这是涉及Zynga竞争武器的“秘笈”。若只是一个员工离开,那还影响不大。但现在是多个员工,其影响就不容小视。

据2010年5月归档的修正起诉书记载,调查过程中,Zynga公开同Playdom高管的邮件,内容展现后者对Pincus的厌恶。Playdom联合创始人Daniel Yue表示,“我的天啊,我非常讨厌Pincus。”Zynga律师认为这些言论造就合理的盗窃立场。

法院3月发出一道禁令,赞同Zynga所述,然后8月又发出一道禁令,禁止Playdom使用所提到的盗窃商业秘密。

Zynga宣称公司前设计总监Rohrl盗窃整个游戏构思及相关创意机制,以Playdom的名义制作内容(游戏邦注:基于不同游戏名称)。Rohrl通过私人Gmail向Yue发送秘密邮件,Yue同意保密内容。他们2009年1月沟通时,Rohrl还在Zynga任职,Rohrl直到2009年3月才得到工作邀请。Zynga宣称Rohrl凭此行为从Playdom那得到额外利益。3月,法院发布禁令,禁止Playdom发行游戏。

Playdom随后承认Zynga文件被前Zynga雇员Chris Hinton转移到Playdom电脑,这些文件被用于同Zynga竞争。但Zynga Playbook仿佛就是所谓“复制内容”,而Playdom的行为似乎只是如法炮制。

Zynga还宣称Playdom入侵Zynga的电脑网络,获取Zynga的用户名单和数据,包括后来名声大噪的《德克萨斯扑克》数据。Zynga宣称Playdom通过自动化脚本盗取公司160万用户的数据,其中包括每位用户所拥有的虚拟货币。第二天,2009年1月28日,Playdom据说向Zynga用户发送教唆信息,说服他们体验Playdom游戏《Poker Palace》。诉讼于2010年11月结束,这发生在Playdom被收购后。

ScamVille丑闻

2009年秋之所以对社交游戏来说意义重大,还有其他原因。Offerpal是一家主要创建Facebook广告的公司,也就是提供众所周知的“offers”服务,若玩家订阅Netflix信息或之类的内容,就会得到虚拟商品。

Offerpal首席执行官Anu Shukla在回应媒体质疑其Offers服务带有欺骗玩家的性质(例如,玩家完全不知自己注册包月订阅或其他“虚假”offers,用户不知道自己是否点击offer页面,附属细则非常不显眼,致使他们落入圈套,购买1年或更久的昂贵服务。只有等到每月账单寄到手中,他们才会发现。)时表示,他们处理的交易数量很多,有时会遇到糟糕的offers,此时他们就会将其剔除。Shukla同时还替那些采用其服务的游戏和应用辩护,声称此项服务支持玩家想要在游戏中购买物品(例如,Zynga《FarmVille》中更优质的耕作工具)时,还可以选择接受Offerpal的offer,完成填写调查问卷或送花给喜欢的人之类的任务,从而在无需付费的情况下获得虚拟货币等内容。

科技博客Techcrunch曾撰文称Zynga 1/3收益都来自导引性销售和其他offers。Zynga内部人员称这不是实况。在众多争议中,Zynga开始采取措施移除欺骗性offers。但Pincus坚持提供CPA offers。

然后TechCrunch又向Zynga发出另外的攻击,上传某视频:视频中平卡斯在某次同伯克利观众进行的交谈中承认自己“曾经为获得营收采取糟糕举措”。在此浪潮中,Facebook决定推迟Zynga《FishVille》的所有运作,因为他们在游戏中发现类似诈骗的offers。6天后,Facebook才再次允许Zynga运作《FishVille》。这次调查迫使Facebook重新制定自己有关offers的规则,缩减具有许可权的供应商名单。Offerpal被排除在外,Zynga短暂删除自己的所有offers,直到确定再也没有诈骗内容。

这个事件导致Offerpal、Facebook和Zynga出现信任危机。Shukla被革职,该公司最后不得不朝其他业务发展。ScamVille事件进一步伤害Zynga在业内的声誉,留下出卖用户以获得收益的污名。由于删除offers,Zynga只好重新设定自己的收入和利润目标。这意味着2010年的收入将低于2009。

获得Yuri Milner的支持

据事后报道,Zynga在2009年的收益依然超过1.21亿美元。其净利润是5300万美元(游戏邦注:当时没有外人知道)。但这并没有影响其用户数量——2.07亿MAU,比前一年的9900万翻一番。Zynga随后宣布,其前三款热门作品囊括公司2009年收入的83%。公司当时的雇员是576人。

尽管出现ScamVille危机,Zynga依然是最抢手的新品牌之一,克莱纳·珀金斯在公司的第二轮扩充融资中投入1510万美元。2009年12月15日,由Yuri Milner管理的俄罗斯投资公司DST同意向Zynga投资1.8亿美元。

Milner在访谈中表示,“我们给某些无形资产贴上价格标签,如团队质量、部门领导位置及企业的惊人发展。从开始交谈到协议达成,该公司全面发展几十个百分点。这是非常惊人的发展。所有内容都纳入评估范围中。”

协议允许某些雇员出售自己的股票,但要确保Zynga依旧保持私有状态。这使Zynga面临严峻资本竞争,需要击退EA之类的挑战。

当问及资本是否会暂缓Zynga公开发售股票时,Pincus避而谈到,“我们创建公司及参与社交游戏领域的方式就是专注于产品、基础设备及发展。我们不想让媒体和舆论有违实况。我们不想让公司在融资上言过其实。

他补充表示;

我们所采取的措施是逐步联手高水准的聪明投资者(他们能够带来新鲜看法,支撑我们的长远目标,且进行分享)。所有投资者之前都曾以自己的方式这么做过。领导者无需证明什么。无论是克莱纳·珀金斯,Marc Andreessen,还是DST。有些集团已在此做好准备,他们希望看到我们进行尝试。资金基础非常重要。关于IPO,这似乎不会加速我们下一年的产品和人员发展。关于上市,若团队尚未准备待续,就会影响执行力。此线路绝非轻而易举。

为什么Milner这位新Web 2.0时代最精明的投资者,会给Pincus这样一笔巨资?Pincus的观点是,5年内虚拟商品市场会逐步变大。若Zynga依然是Facebook最热门的游戏公司,便有望抢占其中30%或更多的市场份额。

Zynga能够向自己的既有用户交叉推广新作品。其他公司在此望尘莫及。Zynga已积累众多数据和经验,知道什么适合用户。其他公司能够复制Zynga游戏的功能,但没有Zynga数据,他们就无法获悉什么功能带来最多营收。虽然Zynga的损失依然很大,但其前景似乎非常光明。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

转折点:真正的游戏设计师

Norwest Venture Partners的风险资本家Tim Chang在2009年秋说道:“现在还很难分析出未来的用户流失率是多少。社交游戏存在一定的用户流失率,就像船底有个洞。但是船只移动速度相当快,以至于你未曾发现有水渗入。”

Zynga发现尽管《FarmVille》轰动了市场,但是其面临的挑战是如何继续前行,如何用新游戏吸引那些因厌倦老游戏而流失的用户。公司明白,尽管可以实现在1周内增加上百万玩家,但是这种情况并不能长久维持。

公司在印度设立工作室,部分原因在于公司想要让自己的雇员能够每天都回家,在大型游戏发布期间可以暂时将他们手上的跟踪责任递交给其他同事完成。

这种措施对不断成长的大型游戏公司来说非常重要,看看EA早期的境况便可知晓。EA经常让员工加班,导致员工对公司的厌恶,甚至有个女员工将自己称为“EA Spouse”。Erin Hoffman随后透露,EA Spouse代表所有工作时间过长的EA雇员发表抗议。随后整个行业进行了充分的调查和自省,EA不得不面对由此产生的诸多法律问题并被迫减轻员工压力。

Zynga也有可能面临同样的问题,因为公司在游戏中添加了新代码,用于分析玩家每日的行为数据。设立印度工作室正属于预防措施。

随着Zynga的成长,公司也意识到需要招募更多的人才来制作游戏。随着越来越多的视频游戏行业资深人士走向公司,Zynga也获得业界越来越多的尊重。有趣的是,甚至连Hoffman都最终走向了Zynga。

Brian Reynolds是Zynga声誉成长的原因之一。Reynolds是传统游戏开发者,受过游戏行业泰斗Sid Meier的指导,与后者配合制作过《文明》、《文明2》、《盖茨堡战役》和《半人马座阿尔法星》等游戏。2000年,他离开Meier的公司,成为Big Huge Games的首席执行官,随后制作了即时战略游戏《国家的崛起》。2008年,该公司被THQ收购。

Bing Gordon将Reynolds引荐给Mark Pincus,Pincus认识Reynolds,因为他在年轻的时候很喜欢同自己的侄子玩即时战略游戏。

Gordon在2010年秋的采访中说道:“Mark是个《国家的崛起》粉丝,就这样Brian Reynolds来到了Zynga。”

Reynolds于2009年6月30日加入Zynga,在马里兰州巴尔的摩市成立新游戏工作室Zynga East。他成了Zynga的首席游戏设计师,招募了许多之前的同事创建起成熟的游戏开发工作室。

Reynolds说道:“我的工作是寻找可以运用到社交游戏中的优秀游戏设计技术,做些新颖的产品。”

Reynolds帮助Zynga挽回公司在游戏设计师心中的形象。2010年2月,Reynolds在拉斯维加斯一年一度的游戏开发者集会Dice Summit上发表了有关Zynga的演讲。当时,Zynga的产品占据Facebook前10名产品中的6位,月活跃用户超过2.39亿。仅《FarmVille》就是逾7900万用户。Reynolds在游戏开发者群体中有一定声望,他的演讲展现出Zynga友好的一面。正是在此次盛会上,Zynga的Mark Skaggs被评为最佳社交游戏设计师。

Reynolds向与会者讲述了游戏玩法和玩家动机以及与这两者相关的话题。他描述了社交游戏的运作原理。他表示,羞耻感成了驱动人们不断回到《FarmVille》等游戏中的原因,因为没有人希望让好友看到自己的农场破败不堪。

Reynolds表示,将主机系列游戏移植到新社交平台上却没有设计某些适合Facebook用户的内容,这完全是毫无意义的举动。这种演讲对那些想要趁着社交游戏的盛行而淘金的开发商极有帮助。Reynolds在大会上表达了自己的看法,但是许久之后才揭示自己正在进行的工作。他说道,自己相信主机游戏和社交游戏能够并存,社交游戏不会成为硬核游戏的威胁。

他认为,自己从传奇游戏设计师Sid Meier处学到的想法仍然适用于Zynga的项目。Meier喜欢尽可能快地构建原型,然后根据用户的行为来改善游戏,Zynga的做法也是如此。同时,在传统游戏设计和社交游戏设计两个领域中,不可对用户提出的意见过于重视,这也是很重要的。以《文明》系列游戏为例,如果设计师满足每个玩家提出的要求,游戏就会拥有累赘的功能,使玩家对游戏的微管理方法变得单调乏味。

在Reynolds加入Zynga之后,许多著名游戏制作者也纷纷进入公司。2010年春,Steve Chiang成为公司游戏工作室领导人。其他加入公司的明星开发者包括前EA和Westwood Studios资深人士Louis Castle(游戏邦注:此人刚刚于近期离开Zynga),在微软关闭制作《帝国时代》的Ensemble Studios后担任Zynga顾问的Bruce Shelley。

与Facebook之间的“古巴导弹危机”

《FarmVille》展现出了病毒式营销的强大力量,Zynga可以通过游戏网络来进行交叉推广,在短时间内将新游戏转变为市场巨作。但是Facebook用户开始抱怨称,他们从玩游戏的其他Facebook用户处收到的推广信息数量过多。于是Facebook对此采取了严厉措施,关闭了将游戏通知发到Facebook用户主更新页面的功能。Facebook也对平台上的其他病毒性交流形式进行限制。

上述做法的结果是,Facebook从用户处收到的有关游戏推广的抱怨减少,但是游戏应用的用户量急剧下滑。2010年春,Zynga在短时间内损失了千万用户。于是,之前不需要做广告的应用开发商现在需要通过广告来营销,而这份广告盈利直接落入了Facebook的口袋。事实上,Zynga不得不开始给Facebook支付更多的金钱。在这个Facebook“后病毒时代”,Facebook游戏公司的运营模式效力已经减弱,风险资本家开始转投更多的手机游戏公司。

随即,新的变故发生。Facebook要求Zynga使用新的Facebook Credits虚拟货币作为Facebook游戏中唯一的虚拟交易货币。Facebook从虚拟商品交易中收取30%的回扣。有些人认为,平台拥有者肯定会设定税费,这种情况是无法避免的。30%的比例与苹果对App Store中应用销售的资费比例相同,也是微软从Xbox Live在线游戏销售中的抽成比例。

Facebook的Deborah Liu辩解称,引进通用货币的作用类似于欧洲发行欧元。这使得不同国家的用户可以在该社交网络上使用相同的货币,而且可以通用于所有的应用中。Facebook声称,这会让玩家更有动力在应用中付费。而且,还能够使国际化交易更加简单。

但是30%的费用比例并不受开发商欢迎,因为Zynga已经习惯于仅向Facebook上的其他虚拟货币供应商支付10%的费用。5月7日,有消息称Zynga准备发布名为“Zynga Live”的网站,作为公司旗下社交游戏的门户网站。Mark Pincus召开全体员工会议公布了这个计划,公司同Facebook间的紧张关系在会议上表露无遗。

前Zynga内部员工说道:“当你在其他人的平台上运营时,危机就会时刻存在。我们是两家共同成长的公司。Facebook对自己的实力不了解,我们也不知道要怎么做。Facebook担心会过于依赖我们,这是就会产生争端。”

Zynga已经创建了FarmVille.com,并计划发布Zynga Live这个承载公司游戏的自有网络。对于行业中的某些人来说,如果Facebook想要以广告和Facebook Credits为中心建立切实可行的业务模型,那么Facebook的这项措施是必要的。Zynga的措施也是有意义的。如果想要让产品面向全体用户,就必须脱离Facebook。

但是,双方的纷争对两家公司都不利。对于Facebook来说,Zynga是只能下金蛋的鹅,他们的游戏能够留住用户。对Zynga来说,Facebook是个必不可少的市场,使公司可以接触到数百万的潜在玩家。

在此期间,Pincus发表言论,提醒Facebook要将注意力放在最擅长的事情上,也就是构建社交网络。

Pincus说道:“Facebook正处在十字路口。他们必须决定成为网络上的社交平台是否是件更为重要的事情,也就是让他们的社交管道遍布全球,比如通过Facebook Connect等更为开放的技术和通信基础结构进行扩张。这就好比成为在线世界的水管工。如果我正处在他们的位置上,我的目标就是成为社交平台。他们必须决定是要成为社交管道还是成为门户网站。我希望他们能够找到围绕社交管道构建起的业务模型。”

他补充道:“社交游戏目前的发展方向应当是成为网络上的开放Xbox Live。如果我们能够获得成就,有始终如一的用户体验,网络出版商和站点能够参与其中,开发商能够以简单的方式创造出令人惊异的游戏体验,用户间的关系通过游戏得到加强,那么我相信社交游戏最终将成为网络上少数能够让用户获得真实体验的产品之一,成为一项庞大的业务。”

达成Facebook Credits交易

Owen Van Natta当时正在Zynga就职。他之前担任过MySpace首席执行官和Facebook首席运营官,在后者的工作时间为2005年9月到2008年2月。Van Natta很了解Zuckerberg和Facebook其他雇员。他正是Mark Pincus需要的那种顾问,能够帮他处理Facebook Credits谈判问题。

2010年2月,Zynga声称公司已正式将Van Natta聘用为高管,双方之前已有过多次接触。

在与Zynga的对话中,Facebook表示半数API调用来自Zynga游戏。这意味着,Facebook上的半数游戏活动来源于此合作伙伴。同时,Zynga声明称,公司正花费大量广告资金来吸引Facebook用户体验公司的游戏。Facebook难道真得想要排挤自己的首要合作伙伴吗?为何Facebook不将Facebook Credits的抽成比例定为3%-4%,向其他虚拟商品交易供应商看齐呢?

Facebook正在进行自我反思。但是Mark Zuckerberg曾提及一点。Facebook不会像中国大型社交网络和游戏公司腾讯那样发展,随着时间推移拥有越来越多自身的游戏。腾讯的生态系统中内容不断增加,但是,Facebook始终只是个社交网络。Zuckerberg表示,Facebook不打算自行制作游戏,公司没有足够的资金来这样做。这便是Zynga的核心竞争力。网站必须依靠Zynga来提供最为流行的应用,所以不会将Zynga排挤出去。

5月18日,Facebook和Zynga暂时化解了Facebook Credits问题谈判陷入的僵局。双方声称已经达成了5年战略合作协定,期间内将在社交网络上互相支持。在此协定下,Zynga同意扩展Facebook Credits的使用范围,最终公司旗下游戏在Facebook上只使用这种货币来进行虚拟商品交易。Zynga同意在每次虚拟商品交易中向Facebook支付30%的全额交易费用。

Facebook和Zynga表示,此次协议对双方都有好处,而Zynga似乎已经撤销了让游戏脱离社交网络和加大对其他游戏网络投资的威胁。双方表示,协议主要解决的是Facebook Credits的问题,结果是Facebook不会削减Zynga的交易费用比例。事实情况的确如此。

但是,还有个协议未被两家公司提及。在这份协议中,Facebook承诺将营销平台并让用户数量成长,这样Zynga旗下游戏才能不断获得新的用户。Zynga的义务是,只要Facebook向Zynga提供足够的用户数量,Zynga同意自己的游戏只在Facebook上运营。其他游戏公司根本无法与Facebook达成类似的协议。

2011年7月,几乎所有的Facebook应用开发商都被要求转向使用Facebook Credits。Zynga、CrowdStar和其他开发商很早就为使用Facebook Credits铺平了道路,因而他们愿意在被强制要求之前就向Facebook支付30%的交易盈利。合约可以解决由此带来的部分问题。Zynga还成功地让Facebook与之谈判,因为公司探索到了其他运营选择,可以减少其对Facebook的依赖性。但是不久之后,双方找到了双赢的方法。

在这场风波结束后,科技博客TechCrunch曾撰文指出,Facebook Credits争端就像技术领域的古巴导弹危机。Gordon对这种说法表示同意。在2010年秋接受VentureBeat的采访中,Gordon说道:“在电子游戏业务出现之日起,内容发行商和平台公司之间摩擦不断。我们在电子游戏领域看到的情况是,随着时间推移,这种摩擦逐渐缓和。构建稳定关系的最简单方法是,让双方都能够在市场中坚持住。发行商和平台公司的首选做法就是相互帮助共同生存发展。”

Zynga和Facebook之间关于Facebook Credits的协议细节公开一年多后,其他游戏开发商开始觉察到问题。他们得知任何公司都无法在Facebook Credits问题上获得特殊关照,甚至是Zynga也不例外。但是Zynga成功地让Facebook做出妥协,以换取公司接受Facebook Credits,30%的费用对Zynga来说显得更加合意。Zynga仍旧显得不慌不忙,该公司在2011年4月前完成向Facebook Credits的过渡即可。而且,Zynga仍然向Facebook独家提供游戏。

《FrontierVille》改变Zynga

尽管Brian Reynolds是Zynga的首席游戏设计师,但是其有些想法似乎并不出众。他在巴尔的摩的团队开发过各种各样的想法。《Fashion Wars》没有取得成功,《Civ Wars》也没有。即便他是游戏行业的资深人士,也需要花些时间来探索正确的社交游戏之路。

在他进入公司大约1年之后,Zynga于2010年6月9日发布了Reynolds的首款成功游戏《FrontierVille》。他负责的Zynga East团队有16名雇员,所以相比Zynga之前的游戏来说,这款游戏花费了更多的时间和金钱。即便如此,这样的团队比起其他公司的主机游戏团队来说仍然较小,后者通常需要上百名开发者参与。

从某个方面来说,这款游戏极为关键。Facebook当年早期限制了病毒性渠道,使Zynga失去了数千万玩家。2010年4月20日,当时Zynga的月活跃用户为2.52亿。但是在《FrontierVille》发布之时,公司月活跃用户数量已下滑至2.16亿。公司必须采取措施来挽救这种局面。

Zynga在《FrontierVille》中呈现出的内容几乎无懈可击。这是款原创游戏,与Zynga之前制作的其他游戏截然不同。游戏的主题是开荒,玩家在荒野中建立家园,努力将其发展成熙熙攘攘的边境小镇。这是款家庭游戏,不只有照顾作物和培育家畜的内容,还要用枪支打败邻居守卫家园。

Reynolds曾经是个偏向硬核内容的设计师。在他为设计师Sid Meier工作时,总是很乐意在游戏中添加原子弹等内容。但是现在他已经变成了休闲游戏行家,对Zynga提升实力和吸引新用户来说至关重要。

《FrontierVille》的深度位于其社交游戏玩法中。在《FarmVille》中,好友可以帮助你照顾农作物,而你或许对此从不在乎。但是帮助他人是《FrontierVille》游戏玩法中的关键内容。你可以帮助好友照顾作物、喂养动物、砍伐树木和复活枯萎的作物。你可以抚养自己的家庭、照顾作物、将恶棍赶出领地、添加邻居并通过帮助他人来提升声望。

Reynolds在VentureBeat的采访中说道:“在这款游戏中,你可以更为简单地查看帮助你的人。这个行业教我学会寻找些简单的内容并让玩家以深层次的方法进行互动。目标在于提升社交体验的质量。”原创是Reynolds坚守的原则。

当《FrontierVille》发布时,马上就吸引了大量的用户,但是随后增长又趋于平缓。问题在于,团队中没有专注于用户数据的分析师,所以从根本上来说,只是一些设计师在闭门造车。随后,当Zynga最终为《FrontierVille》配备全职分析师时,用户量又开始上升。游戏用户量随后攀升至3000万,使之成为公司最大的游戏之一。

创造Zynga新企业文化

《FrontierVille》的成功和Reynolds的游戏开发者团队帮助Zynga弄清楚了自己的身份。随着公司的盈利不断增加,可以雇佣更多新的开发者。Playdom等竞争对手也已经筹集资金,他们可以以相对便宜的价格收购那些受经济危机影响的游戏工作室。所以Zynga认为自己也需要做同样的事情。

受经济危机影响的游戏工作室很多。Zynga最早会查看数百家之后才决定收购。最后,其收购游戏工作室的速度达到每月1家。Zynga的雇员速度也在快速增加。2010年7月,迪士尼决定以7.632亿美元买下Playdom。现在,Zynga不仅需要同EA竞争,还要同迪士尼战斗。

Zynga没有能够与其竞争对手相抗衡的品牌,公司拥有的资源就是人力。2009年3月,Colleen McCreary成为Zynga的首席人力官。这位EA前人力资源主管表示,当公司成长如此迅速且收购如此多新游戏工作室时,构建企业文化并非易事。但是她感觉公司的团队间存在共同点。

McCreary说道:“我们有大量充满激情的员工,他们都很愿意在这个新兴领域中努力。他们在其他地方选择了这份职业,并将社交游戏视为下个流行之物。”

McCreary的团队用核心原则来创造更优秀的公司文化。让人们尽其所能快速工作的唯一方法是激励他们实现公司的核心理想。

McCreary自己是在听取了Bing Gordon的意见后加入公司。她此前同Mark Pincus有过3个小时的谈话,但她拒绝了Pincus转投EA。但是Pincus仍然与她保持联系,在4个月后再次尝试,后来她终于接受了邀请。

她在2010年秋天的采访中说道:“他保持与我的联系表明了他渴望我能加入Zynga。他希望我能够为公司找到最棒的人来构建产品。他希望我们能创造出任何硅谷CEO都想要的东西。对于初创公司来说,你雇佣的前20个员工是好友。接下来雇佣的80个人就是你需要用来完成工作的成员。我们的公司已经发展到如此之大,所以我们必须弄清楚要如何扩张和管理。”

随着Zynga不断成长,公司会接受那些被EA等公司裁员的员工。传统游戏开发者喜欢到Zynga工作,因为他们认为这样就有机会接触到新的用户群体。这些开发者在大型团队中只扮演着很小的角色。但是在Zynga,10到25人的团队在3到6个月内就能够制作出游戏。就Reynolds的情况而言,McCreary表示Zynga在他身上冒了很大的风险,在长期的实验和失败后依然相信他能够制作出很棒的产品。

但是Zynga属下的雇员都压力重重,其工作节奏可以说是惩罚性的。未能达标的员工会感受到很大的压力,对他们来说,要么作出成绩,要么就只能离开公司。

Zynga需要对自己的雇员负责。Kleiner Perkins的合作伙伴John Doerr说服了Pincus采用“目标和关键结果”,Google和英特尔使用的就是这种管理方式。Pincus让他的员工写下每周的三个目标,然后在周五审查他们的完成情况。Pincus表示,这让员工专注于工作。这个系统帮助公司淘汰了表现较差的员工,同时也使他们脱离无关紧要的事情。

有些人将Zynga视为“草根Google”。意思是,公司确实向雇员提供了免费食物之类的福利,但是其福利并不像搜索巨头那样好。

一段时间后,雇员们开始产生疑问,在Zynga究竟要如何发展下去。如果软件工程师想要继续发展的话,他的下个目标是什么?在数个月的时间内,Zynga就解决了这个问题,包括让员工将20%的工作时间花在未来的目标和替代者的培训上。直到2010年秋,Mark Pincus还在花时间同McCreary探讨Zynga每个雇员的发展目标。虽然Pincus很忙,但是他在工作时间总是待在公司,这样员工随时都可以与他交流。McCreary表示,当Zynga出现不高兴的员工时,Pincus也会变得忧心忡忡。

对于那些感觉工作时间过长的员工,尤其是在游戏发布之时,Zynga总是努力让他们得到放松。公司会将工作暂时递交给在印度的工作室,让员工休息片刻。随后,Zynga透露在公司工作不足1年的员工比例为64%,不足两年的比例为92%。尽管如此,许多员工都愿意继续待在公司,即便在Zynga的工作很艰难,但是员工可以获得大量的升迁机会和季度奖金。他们还看到Zynga未来的发展前景,看到自己将来的高薪之日。

更加成熟的Pincus?

当Zynga文化变得越加成熟之时,Pincus亦然。他并不像是《FarmVillains》(游戏邦注:佐治亚州技术教授Ian Bogost在SF Weekly发表的一篇文章)描写的那般“邪恶”,我们可以发现Zynga的很多员工都是来自于其早前初创公司Support.com。如果他并不是一位好老板,怎么还会有如此多的人愿意追随他?

而对于Bing Gordon来说,Zynga兴起于动荡且多变的游戏产业时代。他在2010年秋天说道,除了Pincus,没有人能够更加巧妙地度过这个特别的时期。

Gordon表示:“Mark是个具有先见之明的人,而正是这一优点深深吸引了我。在拓展用户群时他具有深刻的洞察力,明确了游戏的易用性和好友间的交流等重要性。”

Gordon坚信Pincus所做的这些都不是为了凸显自己。他说Pincus总是很乐意待在幕后,并且从不会嫉妒任何员工的成功。想起早前一份关于Pincus领导风格的负面备注,Gordon解释到:“Mark与之前相比发生了很大的变化。之前的Mark并未接触过任何大事业。2008年,人们都还不相信Mark有能力经营一家大公司。因为他早前曾被董事会赶出公司。而这也是大多数投资者所关注的焦点。我在公司的角色便是确保这种情况不会再次发生。”

早前,Pincus非常不善于表达,他总是因为讲话不像一名CEO而遭到议论。当2009年春天,Colleen McCreary出任Zynga人力资源主管时,她便帮助Pincus解雇了30名未能达标的员工。后来,Pincus便更加专注于一些更重要的领域,如商业模式,招聘,企业间的合作关系,未来投资以及游戏本身。在Web2.0峰会等多种演讲场合,Pincus总是不断地强调未来将是社交游戏的天下,并且他们会将将广大社交游戏玩家当成永久用户。这与亚马逊或者谷歌等大型网站的做法一样。Pincus希望引导Zynga走向一个真正的目标,而不只是昙花一现。

Gordon补充道:“我曾经对Mark说过,我认为你能够成为一名世界级的CEO。对于我来说,目前在Zynga的工作就像是我80年代在EA的经历,但是Zynga现在的发展远比那时候的EA快了3倍,并且我所接触的也是一些更加聪明的人。”

“能够创建4家公司便说明他是个聪明人。所以你就必须雇佣一些有才能的新秀,并在他们身上下赌注,给予他们足够的权利,冒险一搏。”

有时候,投资者会不满Pincus的做法而欲将其挤出公司,而Pincus也会收到一些来自于员工的负面反馈。但是风险投资家们和董事会成员并未拥有Zynga的主要控制权。Pincus仍然拥有该公司的最大股份,并且主导着董事会和表决权。这与Facebook首席执行官Mark Zuckerberg在争取投资时占据着有利的协商地位是一样道理。如此Pincus便拥有更多时间能够针对性地改变做法,让自己成为更受欢迎的领导者。他一直在努力学习成为一名大公司的CEO,而这也是他之前从未尝试过的。

但是并非所有人都认可Pincus的做法。风险投资公司Elevation Partners联合创始人Roger McNamee在《纽约时报》中说道:“Zynga本应成为最佳创业典例。但是他最终却成为了哈佛商学院关于创始人过激行为的案例——对于我们来说这绝对是个警示。”

但McNamee曾经与Zynga的最大对手EA首席执行官John Riccitiello合作过,所以他发表如此言论也是情有可原。然而还有一些问题存在。Andrew Trader这名Zynga早期员工在2010年3月离开了公司,后来Pincus却着要求其返还之前公司授予的股票。据报道,Trader不得不针对此事与Zynga做个了结。根据《华尔街日报》报道,这种“追回利益”的行为不只出现在Trader身上,而且这种做法之后给Pincus带来了负面影响。

创建zCloud

Zynga之所以能够创造出完整的游戏网络主要归因于快速发展的“基础设施建设”和新的“云计算”服务,如亚马逊的网络服务,后者将自己数据中心部分出租给其它小公司。Zynga首席技术官Cadir Lee在2010年秋天采访中表示,这种做法能够帮助Zynga更好地创造一个灵活的云端基础设施服务。

Zynga最初基于托管式基础设施。当《FarmVille》发行时,他们便转向于公共云服务,即接受亚马逊的网络服务。这意味着他们必须完全依赖于亚马逊的数据中心,不论他们的要求是否合理。但是从2010年开始,Zynga便打算创建属于自己的数据中心,即zCloud,发展到现在已经越来越庞大了。这是Zynga采用的一种混合方法,即他们既能够使用自己数据中心的资料,也能够根据不同需求而利用亚马逊的公共云服务。

但是这么做的代价却很大。Zynga在2011年将投入超过1亿9900万美元于基础设施中,比起之前的6千200万美元明显增加了许多。但是这种公-私混合云服务能够让Zynga以较低的成本提供与亚马逊同等的服务。如今Zynga旗下有许多正处于不同发展阶段的游戏,而Zynga可以根据不同需要为它们选择不同的服务器。投资于自己的数据中心也能够帮助Zynga省钱。例如,它能够计算出如何减少功率的使用,如何帮助Zynga节省成本等,而这是利用亚马逊数据中心所不能做到的。

Lee表示,《FrontierVille》便受益于Zynga从《FarmVille》中获得的经验。Zynga认为《FarmVille》中的分析,存储,云计算以及游戏应用架构都是该公司宝贵的竞争优势。其后来的很多游戏都借鉴了这些代码和功能。Zynga通过收集和分析数据,以帮助设计师创造出迎合玩家需求的优秀游戏。他们同样也在保护虚拟商品免受黑客侵袭方面下了巨大投资。

Zynga现在可以带着其数千万的用户继续发展,也有可能在短短几周时间内便失去无数用户。他们可以根据需求将游戏转移到专属云服务zCloud上,或者从中移开。在1天时间内,Zynga可以在自动化形式下添加或者排除1000个服务器。每天能够传输超过1TB的内容,而其现在的存储能力已经达到10TB了。(后来Zynga表示其每天能够加工15TB的游戏数据。)但是,现在的Zynga还会不时出现运行中断现象,其主要原因还是归咎于对亚马逊的依赖。

然而Zynga自身的数据中心也具有风险性。如果对于Zynga游戏的需求突然下降,Zynga本身的基础设施将会受到牵连而造成巨大损失。这也是为何Zynga选择既拥有自身数据中心又依赖于外部资源的原因。

作为Zynga基础设施工程的首席技术官,Allan Leinwand表示Zynga更倾向于灵活性。他们既享受着亚马逊提供的“四轮轿车式”服务,同时也在努力创造着不一样的Zynga应用。

Leinwand说道:“也许有一天我们想要的是一辆轿车,或者Winnebago房车。亚马逊的四轮轿车只能帮你触及公共云服务。而一旦我们更加了解自己的应用,我们便需要变得更有灵活性。于是我们创造了zCloud。亚马逊虽然是一个很不错的平台,但是我们的某些应用其实更需要的是跑车或者是18轮的特定汽车。我们必须为满足不同玩家的需求而定制不同的云服务。”

不论如何,Zynga正在尝试着这样的选择,即跻身少数公司的行列创造属于自己的数据中心。只有一些大型公司,如Facebook,谷歌和苹果创建了属于自己的数据中心,而这也是他们在获得了上百万用户基础后做出的决定。多亏了如此操作,这些公司能够进一步拉近与用户之间的关系,也因此坚定了他们统治世界的决心。

走向国际市场

2010年春天,Zynga便开始思考如何恢复发展。除了拥有大量Facebook用户基础和自身的数据中心基础设施,它还迫切需要更多全球用户。美国社交游戏市场的发展在后病毒式传播时代中开始慢慢减速。而且Facebook也并未主导着每一个海外市场。例如在日本,Zynga便需要寻找新的出路。

所以Zynga便在2010年6月与日本软银(拥有日本手机领域绝对的控制权)签订了协议。软银同意投资1亿5千万美元于Zynga在日本的经营活动。那时候,Zynga总共募集了超过5亿2千万美元的投资于社交游戏中,其中更是包括来自于谷歌(他们正规化着创建属于自己的社交网络亿挑战Facebook)悄然投资的1亿美元。

2010年4月,每个月共有2亿5200万玩家在玩Zynga游戏。但是当看到许多游戏的玩家慢慢流失后,Zynga认为是时候开辟新的市场了。在日本,Zynga力图拓展手机游戏,并制造出符合日本用户需求的内容。软银首席执行官Masayoshi Son称,他非常期待能够与Zynga合作创造出强大的社交游戏。Zynga同样也坚信日本拥有与美国一样广大的手机市场和发展前景。

Zynga同样也希望开拓亚洲市场,在这里免费在线游戏刚刚兴起,并且广大玩家都极力拥护虚拟商品。该公司开始积极寻找海外优秀的收购目标,并且为一款游戏同时发行了不同语言的版本。

不断地实践着推广努力,Zynga于2010年8月发行了第一款国际版本的《Zynga Poker》,并针对于Facebook中的香港和台湾玩家发行了中文版本。这款游戏本身就拥有高达2千8百万月活跃用户,但是该公司希望通过这些本土化策略帮助它获得更多用户。Zynga总是无止尽地追求着更多用户,而现在他们更是竭尽全力地去实现这一目标。

很快,Zynga发行的每一款游戏便同时都带有不同语言。但是在日本,事情的进展却不是很顺利。Zynga计划同时在网络和手机两大平台发行游戏。但是在日本,由DeNA,Gree和Mix控制的游戏网络发展得非常迅速。所以那些初创企业团队们很难在此获得较好的成绩,要不就是创造的游戏早已过时,要不就是难以创造出大受欢迎的游戏。如果Zynga未做好万全的准备便强行挤进日本市场,他们可能便需要花费比预期更长的时间才能做出成绩。

走向手机领域

Zynga所采取的最佳行动便是在初尝iPhone游戏市场后便迅速离开了。而其对手SGN则在2009年中旬一头扎进了iPhone市场。

Mark Pincus发现苹果平台仍然很贫瘠。他希望苹果能够将iPhone转变成一个“具有社交性”的设备,就像是Facebook对于社交游戏的做法那样。苹果并不具备在好友圈中迅速推广游戏或者让用户更快发现游戏的功能。所以Pincus希望苹果能够推出应用内置付费功能,让玩家也能够在iPhone上购买免费游戏。

Zynga的竞争者如EA,SGN以及Gameloft深信不疑地坚守于手机市场中。他们砸下重金以学习如何从新的智能手机平台上赚钱。与此同时,Zynga将更多的钱投入在Facebook平台上,从而获得了更多用户并赚得比手机游戏更多的利益。但是Zynga也并未完全离开手机领域,而且当手机市场的前景越来越明朗之时,Zynga也觉得是时候转向这里了。

随后,Zynga便开始追赶其他对手了。它曾试图收购Ngmoco,这是前EA高管Neil Young创办的iPhone游戏开发公司。Bing Gordon非常赞同这一决定,因为他同时是Zynga和Ngmoco的董事,而Kleiner Perkins也同时投资于这两家公司。

但是最终,日本的DeNA于2010年10月以4亿3百万美元的高价收购了Ngmoco。DeNA在日本的手机领域已经收获了上亿美元的收益,他们希望借此收购而拓展西方社交手机游戏市场。

如此收购创造了一种有趣的竞争模式。当Zynga正在与Playfish和Playdom相抗衡时(以及后来的EA和迪士尼),他们也意识到DeNA和日本手机游戏社交网络公司Gree也对世界手机社交游戏的最高统治地位虎视眈眈。而他们也积极地展开与Zynga的竞争行动。

2010年10月,Zynga任命雅虎前高管David Ko为该公司移动部门的高级副总裁。2010年12月,Zynga收购了美国手机游戏开发商Newtoy,该公司开发了《Words With Friends》这款iPhone拼字游戏,在短短时间内便创造了1千2百万的下载量。这是Zynga在7个月以来进行的第七笔收购交易,但这次明显更加针对于手机领域。

Zynga为笔收购支付了5千330万美元,这是Zynga收购其他任何一家公司的最高数额。那时候,Newtoy仅有23名员工,而Zynga本身已有1千3百名员工。如此看来,移动领域是Zynga在除Facebook外趋向多元化的另外一种方式。

《黑帮战争》的制作人Justin Cinicolo在帮助Zynga跻身手机领域中扮演着领导角色。在2010年秋的一次采访中,他表示“Pincus现在更想要涉及手机领域,而我们知道,在这里要想获得如网页游戏的那般成绩必须投入更多的时间。我们已经对社交网络了解透彻了,所以有必要开始拓展其它领域的游戏市场。”

但是与此同时,Zynga也必须面临一些大问题。因为即使是在Facebook游戏领域拥有主导地位,也不能帮助它在手机游戏领域中获得更好的发展。

《CityVille》引起轰动

Zynga曾经有段时间一直在寻找能够延续《FarmVille》热潮的后续游戏。《FrontierVille》虽然拥有所有优秀的游戏元素,但是却未获得如《FarmVille》般的广泛关注度。所以该公司将更多的精力投入于下一款游戏中,即由经验丰富的游戏设计师Mark Skaggs领导创造的游戏。Skaggs先创造出一款大型游戏模式,然后交给其他人完成剩下的工作,而他自己则立刻转向新游戏开发。

Zynga于2010年创造了《CityVille》。曾经致力于《FarmVille》并且是前EA设计师的Skaggs表示,《CityVille》的开发团队中有95%的人从未参与游戏开发工作。这个团队在开发游戏中借鉴了Zynga其它游戏中一些成功的机制,如收集奖励,抢夺战利品等。随后他们便开始关注如何才能让一款城市类游戏更有趣。结果他们创造了一款简单的城市模拟游戏,虽然一次游戏只需要几分钟时间,但是却能让众多玩家一天内反复回到游戏中进行体验。

他们创造的这款城市模拟游戏便是《CityVille》,其中包含了一些新的Zynga游戏元素。游戏中,在城市地图上有一些移动的好友动画和图标,如此设置会让玩家感觉这好像是一种即时游戏,同时游戏还渲染了3D多边形表达方式,即允许城市转动,并让玩家从不同视角观看游戏画面。同时游戏中还有新手教程,帮助新手玩家更方便地进行游戏,它既包含了《FrontierVille》的社交功能,即允许玩家在好友的帮助下前进,同时也允许玩家购买Facebook Credits而更快地前进。从外表来看,这更像是《模拟城市》或者Playdom的《Social City》。但是Zynga的游戏更简单且更适合Facebook平台,即并未涵括太多交互性内容。

Zynga在2010年11月17日宣称将发行《CityVille》,该游戏还同时具备四种语言的版本,并且这是Zynga首次定位不同区域而发行的游戏。但是在公告发布后的数周,Zynga还一直在调整游戏。直到12月2日的1点22分,Zynga最终发行了这款游戏。发行后的24小时内,共有超过29万名玩家体验了游戏。这是Zynga有史以来最好的发布成绩,甚至高于《FrontierVille》的11万6千名玩家。

更多玩家继续涌向游戏。在发行5天后,《CityVille》便吸引了650万名玩家。他们在游戏中创建了超过270万个家和50万间面包房。这款游戏的时机把握得非常好,因为这时候《FarmVille》已经慢慢衰退了,而这也促使Zynga的月活跃用户从2010年春天的2亿6千万下滑至1亿9380万。但是随着《CityVille》的发行,这个数值将慢慢回升,在发行的第12天,已经有2千6百万玩家体验过这款游戏了。

在接受采访时,Zynga副总裁,也是领导《CityVille》创作的Mark Skaggs说道:“这种感觉很有趣,我们好似再次体验了《FarmVille》发行时的那种乐趣与兴奋。我们瞬间充满了干劲并希望将其做得更好。”

《CityVille》的发行明确体现出Zynga在社交游戏领域不可阻挡的实力。在二手股市中,Zynga现在的估值已经达到了50亿美元,远远高于竞争对手EA,后者收益为40亿美元。《CityVille》在2010年12月24日用户数首次赶上《FarmVille》,尽管这时候后者还拥有5千8百万名用户。1月3日,《CityVille》超越了《FarmVille》的最高纪录8千376万用户,这是在2010年3月获得的记录。2011年1月14日,《CityVille》的用户数突破了1亿,这仅仅是该游戏发行的第43天。在电子游戏的50年发展史中,《CityVille》是用户数量增长最快的一款游戏。如此也将Zynga的月活跃用户数带至2亿9660万。在Facebook中,《CityVille》的用户数甚至是排名第二的应用的5倍之多。

作为Zynga董事会成员,Bing Gordon表示《CityVille》是合理安排游戏内部奖励的产物。他认为该款游戏的成功证明了游戏是网络中一种“社交通用语”,在这里我们会遇到不同人并且通过与他们玩社交游戏人加深彼此之间的关系。《CityVille》的成功推动了Zynga在2010年第一季度的利润增长,用户购买游戏内部虚拟商品的次数变得更加频繁了。

《CityVille》的成功吸引了更多赞助商的关注。在2011年5月,Zynga与梦工厂签订了协议,将在游戏中推广他们的电影《功夫熊猫2》。而用户可以在他们的城市里建造《功夫熊猫2》主题的免下车电影院。Zynga并未拥有较有名的游戏专营权,但他们知道如何通过虚拟商品植入品牌内容,从而为游戏创造更多价值。

《CityVille》的成功让Zynga希望能够获取更大的成功。其随后便发行了《CityVille Hometown》,即该游戏的手机版本,并且他们还宣称将在腾讯平台发行中国版的《CityVille》(即《星佳城市》)。后一行动能够帮助Zynga更好地走进腾讯这一拥有超过6亿7400万中国用户的平台。

《星佳城市》由Zynga位于北京的工作室开发(其前身是Zynga在2010年5月收购的XPD Media)。该工作室的开发团队成员都是来自于中国的设计师,美术人员以及开发者。《CityVille》可以说是迄今为止Zynga旗下最全球化的游戏。

淘金热或泡沫?

2011年1月,Zynga秘密获悉公司估值。据第三方评估公司表示,Zynga当前的估值是49.8亿美元。随着公司的发展及Facebook和Groupon价值的提高,Zynga也从此泡沫阶段中受益,因为投资者纷纷寻找方式想从此Facebook现象中大捞一笔。只有少数投资者能够真正在Facebook投资,但其股份的需求日益攀升。

2011年2月13日,据《华尔街日报》报道,Zynga在首轮融资中筹得2.5亿美元,投资者认为Zynga估值约在70-90亿美元。这极大超越二级市场的50亿美元估值,这说明投资者非常热衷于投资社交游戏及Facebook相关项目。而此时,Zynga依然凭借《CityVille》处于优势地位,游戏MAU达2.758亿。

EA估值约为60亿美元。基于估值的比较非常疯狂。EA截至2011年3月的财政年度营收有望高达37亿美元(非GAAP算法)。动视暴雪2010年的营收为48亿美元。EA和动视都有7000多名员工。二者从非GAAP角度来看都获利丰厚。

大家关于Zynga的估值都有些夸大。据《华尔街日报》内部消息透露,Zynga 2010年的营收有望达到8.5亿美元,净赚4亿美元(游戏邦注:据Zynga后来的IPO文件数据显示,公司实际创收5.97亿美元,净赚9000万美元)。Zynga有1500多名员工,平均每月购买一家游戏工作室。相比之下,EA称,截至3月31日公司的财政年度营收有望达到7.5美元。

回到去年10月份,据二级市场(其中公司员工和股东能够向资金雄厚的投资者出售自己的股票)的有限交易量显示,Zynga估值只有52.7亿美元。当时,Zynga估值超过EA。深知泡沫现象的观察者问道:Zynga如何在3个多月里将自己的市场价值翻一番?

Zynga如今的营收是2010年的11倍多。而动视暴雪则是去年的2.7倍,EA约是1.7倍。大家大多会基于Zynga的潜在营收和收益估算公司价值;由于公司发展迅速,投资者自然会给出更高估值。Zynga显然是纯社交媒介技术中的一员,Facebook也在其中之列,其估值在最近融资中上升至500亿美元;Groupon估值超过60亿美元;LinkedIn正在筹备上市;Twitter估值介于80-100亿美元。

Zynga因采用免费游戏模式(其中玩家能够免费体验游戏,但需要付费购买虚拟商品)吸引众多投资者的关注。亚洲游戏公司也采用此模式,值得注意的是腾讯在中国股票市场的价值约460亿美元。但很多中国在线公司的估值都在40亿美元以下。

有人觉得Zynga估值并不真实,因为它处在投资泡沫中,此数值最终定会缩水。但传统游戏公司明白,Zynga可以通过自己的估值购买具有实际价值的资产。Zynga每月都会购买小型游戏工作室,但它已积累足够资金,能够买下传统游戏开发公司。它能够在新作品中投入充足资金,而此作品则有可能威胁其他公司的地位。这就是泡沫价值转变成实际价值的方式。

很多大型游戏品牌意图在2011年进攻Zynga核心市场——Facebook游戏领域。但要挤掉Zynga非常困难,Zynga已进入某种自我延续的状态。Zynga需要在营销中投入大笔资金,以保持自己的地位,但只要它依然拥有资金,它就能够从中赚取更多,Zynga是Facebook平台的“猛虎”。公司同时还转投手机领域,将其视作下步扩张的目标市场。

当时,没有人知晓Zynga下轮投资的具体内容。但Zynga随后表示,公司在2月份融资4.9亿美元。这笔巨额资金令Zynga得以推迟公司IPO,直到顺利达成某些目标(游戏邦注:例如收益水平、Facebook之外的多元发展、手机领域扩张和国际市场扩张)。所有这些目标令Zynga得以收获让投资者放心的收益。之前,Zynga已融资3.6亿美元,所以新回合的融资超越先前所有数额之和。

到3月份,Zynga估值是100亿美元。到5月底,估值变成139.8亿美元。当时关于Zynga意图上市的谣言遍布各处。反对派则表示,没有公司能够以如此快的速度增值,这不过是另一个硅谷泡沫。

最终获得认可

在2011年的Dice Summit上,700位游戏设计师及其他业内杰出人士听到的是关于《FarmVille》和《愤怒的小鸟》之类的作品如何瓦解传统游戏领域的公开谈论。Zynga派出的代表是Bruce Shelley,他是曾制作出《Age of Empires》等作品的著名设计师,现在是Zynga的咨询顾问。

Blizzard Entertainment主管Mike Morhaime表示,他会玩《Words With Friends》(这是款类似Scrabble的iPhone文字游戏),这样他就能够同老朋友保持联系。

EA BioWare部门的联合创始人Greg Zeschuk表示,他会把其他人拉到自己办公室,向他们展示Facebook游戏《CityVille》,然后说,“过来,来看看未来游戏的样子”。他表示,游戏设计师如今能够凭借这些通俗易懂、便于操作的游戏快速覆盖众多用户。

Zeschuk表示,“我们第一次能够凭借如此简单的内容囊括这么多用户。”

现已倒闭的Ensemble Studios的联合创始人及《Age of Empires》设计师Bruce Shelley非常着迷于Zynga的《FrontierVille》(由其好友Brian Reynolds制作,他是游戏领域的元老),决定也涉足Facebook游戏开发。

Shelley表示,“这款游戏富有粘性,是款真正的游戏。这说明游戏设计已步入前所未有的新领域。”

峰会上,Bing Gordon获得电子游戏领域的最高荣誉。他凭借自己在游戏领域的25年投入获得Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences颁发的“终身成就奖”。Gordon是EA的早期员工,担任公司首席创意总监。他本可以在于EA任职25年后退休,但作为Kleiner Perkins合伙人,他雄心勃勃。他投资Ngmoco(后来以4.03亿美元售出的手机游戏公司)和Zynga。Gordon的奖项不仅是对他过去的认可,也是对他当前成就的肯定。这意味着Zynga、Mark Pincus和社交游戏如今都在游戏领域占有一席之地。

Gordon曾表示,“25年后,我们都能够一炮打响;但记住这点:我们都处在游戏的黄金时代。”

这无疑是Bing和Zynga的黄金时代。

但其中依然夹杂些许紧张和怀疑元素。育碧著名游戏设计师Jade Raymond表示,看到用户在公司制作的硬核掌机游戏中投入的时间越来越少,他们感到很沮丧。但多数游戏公司都积极在社交和手机领域制作数字游戏。Zynga改变整个游戏行业。

在隔天的演讲中,Gordon告诉Dice观众,Zynga着眼于更广泛的体验含义。早在2004年,EA就发现公司游戏所获得的体验时间超过电影。EA《Club Pogo》2004年的体验时间多达2.25亿小时,而《Madden NFL》只有1.8亿小时,《光晕 2》只有1.5亿小时,就连当时最热门的电影《怪物史莱克 2》也只有1.26亿小时。在Gordon看来,游戏设计非常强大,将超越游戏领域的界限。他将此称作“一切事物的电子游戏化”。游戏设计师的想法是深入非游戏网站,获取更多用户。社交软件重新改造所有内容,从企业学习到教育。尽管他推崇Zynga游戏,但他还是认为“《魔兽世界》是新托尔斯泰”,以此表示对硬核游戏的尊重。

观众倾听Gordon间或的闲聊,这汇集掌机和社交领域的经验积累。他是行业的桥梁。他让Zynga脱离被嘲笑的境地。UBM Techweb Game Group执行副总裁Simon Carless表示,“现在的情况要比过去缓和很多。社交开发商运用更多游戏设计理念,他们的游戏比以往更富趣味。硬核游戏开发商如今正在学习如何创造更具社交性的体验。”

谷歌通过Google+拉拢Zynga

谷歌秘密向Zynga投资1亿多美元,此消息从未向外透露。一个原因是Zynga不想破坏自己同Facebook的关系。但谷歌显然想要制造二者的隔阂,因为它计划推出自己的社交网络。在经过众多准备和媒体猜测后,谷歌最终于2011年1月28日公布Google+。2周后,此服务平台就获得1000万用户;4周后,用户就增至4000万。

公司缓慢发出邀约,这样它就能够逐步添加功能,维持良好服务。2011年8月,此服务向游戏开放。其工程高级副总裁Vic Gundotra表示,用户共同分享的体验和人际关系一样重要,所以Google+游戏的目标是将在线游戏体验变得同现实生活娱乐一样有趣和有意义。这意味着谷歌将着眼于游戏中的社交分享,游戏内容将由第三方提供。

在谈到Facebook垃圾型游戏消息通知时,Gundotra表示,“Google+的游戏会在用户想要体验时出现,在他们不想体验时消失。”换而言之,谷歌不会让垃圾信息包围非常游戏玩家。

平台已发行16款游戏,其中包含《Zynga Poker》。同样,Zynga尝试跳脱Facebook,进行多元化发展。谷歌似乎有望发展成同Facebook一般规模的主流平台,甚至还会从中分走部分用户。

谷歌之所以如此急于将游戏投放至Google+社交网络的一个原因是,这是他们向Facebook施加资金压力的方式。

PrivCo(游戏邦注:这是评估私营公司财政数据的一家纽约公司)运营副总裁Joseph Ranzenbach发表某些关于Facebook-Google竞争的有趣分析。他表示,Google+游戏会严重损害Facebook的主要收入来源。

这就是因为谷歌初期只在第三方虚拟商品中分成5%,而Facebook分成30%。若开发商在Facebook上出售游戏虚拟商品,他们就得使用Facebook Credits,Facebook就会从每笔交易中分成30%。这令很多开发商心存不满。

据PrivCo估算,Facebook收入约有2/3来自广告,而另外1/3则来自Facebook Credits。所以Google+正在威胁Facebook的1/3收入。当然很多Facebook广告都置于用户游戏页面,这样就有很多广告收入同游戏密切相关。

谷歌找到攻击Facebook的方式,而Zynga是此迷局中的重要棋子。未来Zynga也许就无需烦恼自己过于依赖Facebook。随着Google+的诞生,Zynga有望变成社交平台中的王者。

寻找接班人

Zynga已变成快速升职的地方,员工有望以惊人速度获得提拔。Mark Pincus坚持的一个原则是员工要试着找到自己的接班人。此原则也适用于他自己。

多年来,Zynga出现众多Pincus的接班人。Bing Gordon给他提供建议,但公司还有Vishal Makhijani之类的运营总监。前MySpace CEO Owen Van Natta,同时是Zynga天使投资人,于2010年初加入公司。他是公司执行副总裁,主要负责营收策略、公司发展、国际扩张和品牌方面。

但2011年6月3日,Zynga聘请前EA第二大决策者John Schappert,担任公司首席运营官。Schappert此举清楚说明(同其前辈John Pleasants 2009年转投Playdom一样),社交和休闲游戏是电子游戏领域的一股巨浪。行业元老如今更愿意游走在此浪潮的前沿。

Schappert在EA任职很久,起初只是游戏程序员,1994年他创建自己的游戏工作室Tiburon,其团队替EA制作《Madden NFL》,后来EA于1994年收购Tiburon。Schappert从毫不起眼的角色慢慢变成公司第二主要决策人,但他2007年跳槽加入微软,担任Xbox Live在线游戏业务的主管。他在Pleasants离开EA转投Playdom后,重返公司。在EA,Schappert促使公司将扩张方向转至数字游戏领域,同Zynga进行竞争。到2012年3月,公司的数字游戏收入有望增至8.33亿美元。

Pincus终于找到自己在Zynga的接班人,此管理人员也是投资者非常信任的电子游戏领域专家。Van Natta成为公司商务总监,但他最终辞去自己在Zynga的职务。他依然是公司董事会成员,但Schappert的加入令Van Natta显得有些多余。

显然,Zynga“参谋”Bing Gordon主要负责招贤纳士。而Schappert的职责则是维持整个公司的秩序,公司持续以每月收购一家公司的速度扩张。他还负责快速扩充已发行作品的内容(游戏邦注:就是当团队成员即将完成手头项目时)。Schappert给Zynga带来更多游戏信誉,这意味着他对公司未来IPO所起的作用很大。不满Pincus的投资者将非常放心Schappert。虽然从宣布Schappert离开到他后来转投Zynga有长间隔,但EA并没有因Zynga聘请Schappert而将其告上法庭。

Schappert的加入伴随若干重要事件,这些意味着Zynga的成熟。Zynga起诉巴西重要社交游戏公司Vostu抄袭公司作品。Zynga还推出《Empires & Allies》,这是公司的首款战斗社交游戏,由制作《Command & Conquer》系列的EA元老完成。《Empires & Allies》发展很快,给以卡通为主的社交游戏市场添加新类型,Zynga意图覆盖各种题材。很快,类似于《Pioneer Trail》、《Adventure World》的其他游戏都将诞生。似乎确保公司能够顺利进行首次公开募股的所有必要工作都已准备就绪。

EA的反击

今年夏天,Zynga设法获得业内“重要猎物”。《宝石迷阵》和《植物大战僵尸》之类热门休闲游戏开发商PopCap Games公开探测自己的IPO形势。PopCap员工期盼已久,希望能够获得某种形式的回馈,终于这一切即将到来。Zynga想要收购PopCap,愿意倾注自己的大半资金换得这笔交易。

被问及如何看待有关Zynga估值时,PopCap CEO Dave Roberts表示,“大家要谨慎看待基于二级市场的估值。我并不是说Zynga不是颇具价值的公司,事实上我觉得公司价值很高。但没有人会相信这是合理市场估值。同样当少量普通股由其他公司掌握时,你也要非常小心。假如若微软在某项目中投资5000万美元,他们丝毫都不会在意,因为这对他们来说只是小数目。但这并不意味着公司其余资产就价值很高。我觉得只有等Zynga真正上市,我们才能知晓其真实价值。”

后来,7月12日EA赢得PopCap。EA同意支付7.5亿美元的现金和股票,此外,若顺利实现目标,将额外追加5.5亿美元。

据《纽约时报》报道,Pincus据传曾试图以9.5亿美元现金收购PopCap Games。但后来PopCa听说Zynga有增税回收记录,还取消股票回馈奖励,且公司内部存在激烈斗争,于是决定回绝Zynga的要约。相反,PopCa接受EA 7.5亿美元现金和股票(以及5.5亿美元的追加款项)的要约。

关于此交易的解释非常奇怪,PopCap交易达成几个月后,才有消息称是由于Zynga取消股票奖励,PopCap才选择EA。从表明来看,EA的要约要比Zynga有吸引力很多。EA得到PopCap,而Zynga没有,这令人心存疑虑。为什么PopCap会不想同Zynga共事呢?Zynga内部是不是存在什么问题?Pincus的确收回某些早期员工的股票期权。

据报道,有三个匿名消息源称,《愤怒的小鸟》开发商Rovio曾放弃Zynga提出的22.5亿美元现金和股票收购要约。Rovio清楚表示公司打算上市。

PopCap联合创始人John Vechey曾在访谈中表示,EA就像场精彩的比赛,因为公司CEO John Riccitiello在游戏领域知识渊博,清楚PopCap擅长什么。EAi(游戏邦注:EA的手机和休闲游戏工作室)主管Barry Cottle表示,PopCap是在Facebook和手机领域发展较快的休闲游戏公司之一。公司每年创收1亿多美元,且以30%的速度发展。PopCap首席执行官Dave Roberts表示,《宝石迷阵》的销售额占公司总营收的40%,另外有20%的收入来自《植物大战僵尸》。但公司诞生于2000年,早于社交游戏时代,按资历来算,应该是PopCap收购Zynga才对。

此时,EA有款巨作《模拟人生》(这款游戏在PC和掌机平台售出1.4亿份)推出Facebook版本《The Sims Social》。这款热门游戏由Playfish制作,此社交游戏公司2009年被EA以至少3亿美元的价格收购。就Zynga在此社交平台的主导地位来看,这是非常惊人的反击。

据社交游戏网络Raptr基于平台1000万用户所做调查显示,很多《The Sims Social》用户都来自Zynga游戏。EA自己的社交游戏及《模拟人生 3》用户只占《The Sims Social》总玩家的15%。而Zynga玩家则占这款游戏玩家总量的50%。

the-sims-social(from thezombiechimp.com)

9月12日,《The Sims Social》的用户数量超过《FarmVille》。到10月12日,《The Sims Social》成为Facebook排名第二的游戏,MAU达6600万(游戏邦注:而《CityVille》有7600万)。若这款游戏有近一半玩家来自Zynga,那么就有3300万Zynga用户发生“叛变”。当然不是所有Zynga玩家都是在放弃Zynga游戏的前提下选择《The Sims Social》。但《CityVille》玩家确实已由原本的1亿人跌至当前水平。

EA高管Jeff Brown笑称,“《The Sims Social》证明这些玩家是能够通过争取获得的,若他们会发生转移,我们就有办法获得他们。”

就目前运作情况来看,《The Sims Social》显然无法追上《CityVille》。由于《The Sims Social》发展速度的下滑,及Zynga投入额外营销资本,《CityVille》又再次呈现发展势头。

姗姗来迟的IPO文件

5月末,有消息透露Zynga已经决定申请首次公开募股(游戏邦注:下文简称IPO)。LinkedIn的IPO效果很不错,因而行业普遍认可Zynga走这条路线。

6月末,有传言称该公司将募得20亿美元,Zynga的市值将从150亿美元提升至200亿美元。这样看来,Zynga的市值将是EA的3倍。最后,Zynga于7月1日在证券交易委员会签署了注册表格,所募资金逾10亿美元。随着IPO的大门逐渐开启,当时筹备申请上市的科技公司已超过80家。

对于游戏行业的人来说,看待此事的想法各不相同。那些讨厌Zynga的人提出众多理由,表示这个只会复制原创作品的公司根本没有如此大的升值潜力。但是,Zynga的S1文件公布了此前从未对外公开的财务信息。

Zynga的S1文件中谈到,在4年的时间里,公司营收逾15亿美元,现已累计现金达9.956亿美元。公司旗下玩家每天使用公司服务的累积时间达到20亿分钟。公司有2268名雇员,月独立用户数有1.48亿,分布在166个国家,月活跃用户数量逾2.32亿(游戏邦注:某些用户玩多款游戏)。以每天为单位来计算,Zynga的日活跃用户数从2009年9月的2400万提升到现在的6200万。这个数值比Facebook上其他社交游戏公司都要高得多,这也是为何Zynga如此受期待的原因之一。所有用户每天的互动次数为4.16亿。Zynga每天处理的游戏数据达到15TB。

Zynga在这份文件中透露了其他有趣的指标。根据文件所述,有2.5%的用户在游戏中付费购买虚拟商品,也就是说付费用户数量仅为770万。从某种程度上来说,这意味着Zynga是十分脆弱的。如果有其他公司抢走这770万用户,那么Zynga的盈利就会迅速下降。但是从另一个方面来说,这也是个巨大的机遇。Zynga只需要将付费用户比例提升到5%,就能够让公司的盈利翻倍。这便是Zynga不断寻找多种盈利途径的原因。此类数据对行业来说是极有价值,Zynga上市似乎让行业开始认清哪些是对其自身至关重要的东西。

Zynga在文件中公布的另一个有趣内容是,公司声称其从《FarmVille》中赚得的钱比以往更多,即便这款游戏的发布时间可以追溯到2009年。《FarmVille English Countryside》之类的扩展内容促进了盈利的提升,尽管游戏已经发布两年之久,《FarmVille》目前仍然拥有巅峰时期的半数用户。相比之下,多数主机视频游戏在出售仅数周后,玩家便开始转向其他的新游戏。因而,就用户积累和留存情况而言,Zynga做得很不错。

广告盈利只占总盈利的5%左右。Zynga也有机会在这方面获得提升,但是自从“ScamVille”事件之后,公司在这方面变得小心翼翼,因为上述事件危害到Zynga与用户间的良好关系。

但是Zynga并没有在公布文件后直接上市。证券交易委员会还有些疑问,Zynga必须修改其文件,让监管者满意。随后,股票市场逐渐开始波动。2011年8月5日,随着欧洲经济危机逐步扩散,股票市场再次呈现下滑态势,情势不容乐观。

修改文件中的某些内容给公司带来更大的困难。当Facebook游戏开发商发现Facebook和Zynga之间的紧密关系后,他们感到极为愤怒,原因是Zynga透露和监管者签署的新内容显示,Zynga从平台处获得了其他游戏公司显然无法得到的实惠。在文件中,Zynga阐述在1年前同意让游戏采用Facebook虚拟货币Facebook Credits时,与Facebook达成1项特别交易。在这项交易中,Zynga同意按照Facebook Credits的标准费用比率,将游戏中虚拟商品盈利的30%支付给Facebook。

同时,Facebook必须同意帮助Zynga实现游戏的成长目标。正如最初所报道的那样,就Facebook上放置于Zynga游戏页面的广告而言,Facebook并不同意向Zynga支付广告收入回扣。根据Facebook发表的声明,Facebook表示双方曾经的确商讨过广告盈利分享交易,前提是Zynga选择将自己的Facebook游戏移出平台,但是这项交易最终并未达成。每个开发商支付的费用比例都是30%,Facebook表示平台平等对待所有的开发商。

但是令其他开发商感到不快的是Facebook对Zynga发展目标的支持。据报道,Facebook承诺在5年的协议期内保持Zynga游戏的发展。

Digital Chocolate首席执行官Trip Hawkins曾对此表示:“我们都知道Zynga存在合同上的优势,但是居然达到让其他开发商难以在Facebook立足的程度。今年的政策改变已经影响到了盈利和市场占有,现在发现这个市场还缺乏公平竞争,这着实令我们感到心寒。他们之间的关系极为复杂,就像是场夫妻双方仅为金钱而组建起的婚姻。你丝毫感觉不到双方真正从这场婚姻中享受快乐或自由。讽刺的是,他们居然还能够利用更多的好友。”

在与游戏开发商的交谈中,Facebook努力让开发商冷静下来,解释称平台并非以某种损害其他开发商的方式偏袒Zynga。事实上,Zynga此前已数次表现出对这种关系的厌恶。

同时,Zynga时断时续的IPO渐渐变成一场笑话。自8月份起,大量IPO最终都没有实现。最后,有传言称Zynga将在11月上市。接下来,时间又推迟到了感恩节之后。但是,Zynga最后决定将自己的首次记者招待会延迟到新总部建成之后,这栋被称为“狗屋”的高楼可以容纳1700名员工。

大爆发

Zynga在短期内拥有了2700名雇员,需要大量的工作场所,许多人移到旧金山市场南附近的前世嘉美国总部大楼中。但是随即便有问题浮现出来:Zynga在2011年只发布了数款游戏。那么,这些游戏开发者都在干什么呢?如果10人左右的小团队花费6周的时间就能制作出《FarmVille》,那么从理论上来说,Zynga现在拥有的雇员数每年足够制作出1600款左右的《FarmVille》。

当然,游戏开发的成本逐渐提升。游戏制作需要耗费更长的时间(游戏邦注:《FrontierVille》耗费1年左右时间才制作完成),所需团队也变得更大。Zynga从未对外公开每个团队的成员数量,这个信息算是商业秘密。但是许多观察者认为,Zynga公司存在严重的冗员现象。

据VentureBeat报道,《Mafia Wars 2》这款Zynga最成功的游戏之一的续作,由80人耗时18个月完成。Zynga于9月20日对外公布这款游戏,10月10日正式发布。游戏以3D Flash动画为特色,但是总体来说仍为二维游戏。游戏的用户量增长到1700万以上,但是随后开始下滑。

但10月11日的Zynga盛会表明,这些雇员显然都很忙。这次盛会就像是Zynga的小型E3游戏展览。在餐厅举办的记者招待会中,Pincus透露了10款手机和社交游戏原创作品。这些作品并非都处在准备发布的阶段,但是可以想象到,未来将会出现产品大爆发的情形。

这次盛会是精心为媒体、分析者和投资者准备的,公示了即将出现的诸多正面消息。每个新作品都显示,Zynga正打消投资者怀疑公司是否还有能力稳居榜首的疑虑。数个月以来,Mark Pincus这位身价即将达到数十亿美元的人首次出现在舞台上。

首先,他讲述了Zynga在2007年的辉煌岁月,那时公司刚开始针对Facebook制作游戏。他说道,那时团队从街对面的Culinary Academy中雇佣了某些学生,在公司的小总部内烹制食物。Amelia属于这批学生之一,她随后成了Zynga游戏《Cafe World》中的虚拟主厨,现在她成为了真正的主厨。他让记者们转向上方看,成排的雇员站在建筑物上层的开放走道上。Pincus为当天占用餐厅向他们道歉。

Pincus并没有主持完整场盛会。Pincus只是为其他Zynga高管的陈述做个铺垫。他让各个领域的专家上台描述他们自己的游戏。当他介绍到公司的首席运营官John Schappert(游戏邦注:他此前在EA工作)时,他表示Schappert实现了自己的目标,成了他的接班人。

Pincus说道:“我们每天都在挑战自己,说服你们玩游戏。你们很忙,没有时间做下来玩游戏。但是,我们确实认为玩乐是生活中必不可少的主题和行为。我们正在构建的所有产品背后都潜藏着一个任务,那就是构建玩乐的平台。”

Pincus表示,Zynga的基本设计原则是初次用户体验(游戏邦注:可简称为“FTUE”)。让玩家对Zynga产生印象的最佳机遇是游戏中的前3次点击。他表示,对休闲游戏而言,你需要在前3次点击时吸引到玩家,前5到15分钟的游戏体验应当像是“享用丰盛晚餐”。

Zynga Direct和Project Z

在记者招待会上,Pincus提到公司的创新项目Zynga Direct,公司在这个项目上已经投入了两年时间。这是个围绕Zynga游戏创造更多社交互动的平台,无论用户使用的是电脑网络还是移动设备。Schappert随后描述了Zynga Direct的部分内容,可称为Project Z,这是个Zynga玩家可以用来玩Zynga游戏的在线站点。Schappert表示,Project Z是个“社交游戏游乐场”,玩家可以在享受自己选择的游戏。但是,他对该项目的描述也仅仅止步于此。

Project Z将是个独立的网站,只含有Zynga的游戏。网站将使用Facebook Connect功能来构建玩家好友社交图谱。随后,你可以直接访问Project Z玩Zynga的游戏,而不用登录Facebook。这是Zynga的自有平台,类似微软的Xbox Live在线游戏服务。在这个平台上,Zynga无需支付30%的盈利费用。

Schappert说道:“Project Z是个Facebook Connect平台,让Facebook好友在自己独立的环境中玩游戏。我们通过数据和交谈掌握了大量的玩家相关信息,这就是玩家们想要的产品。”

1年多之前,整个世界都未曾听说过这些脱离Facebook的项目,当时Zynga正因Facebook Credits的问题威胁要离开Facebook。Zynga从未停下开发这些项目的步伐,尽管公司与Facebook的关系有所缓和。但是,这些项目经历了数次暂停和重启。问题在于,致力于此就意味着Zynga要创建自己的社交网络。而这种做法面临的难题就是,Facebook已经成功建立起了大型社交网络,用户数量正在向8亿迈进。Zynga需要弄清楚,如何能够让自己的社交网络有足够的差异化,将Zynga粉丝吸引到这个独立的网站平台上。

现在看来,Zynga当初声称想要脱离Facebook,与玩家建立起没有中间人的直接关系,这并非是公司威胁Facebook的说辞。

手机部负责人David Ko描述了5款新的手机游戏。手机游戏市场比Facebook游戏市场更大,所以Zynga必须努力提升公司在该市场中的份额,才能保持快速成长、脱离Facebook并在上市前持续良好的表现。Ko已经在这个新部门中投入了5300万美元,正在不断收购更多的手机游戏开发商。

Zynga还展示了其他新的Facebook游戏,比如《Zynga Bingo》、《Hidden Chronicles》和《CastleVille》。该公司声称,《Mafia Wars 2》将登陆Google+平台。这场新闻发布会都旨在向外界表明,Zynga的雇员此前都很繁忙,公司现在正向各个领域扩张。

Pincus最后为大会做了总结,称Zynga始终坚持自公司成立以来从未改变的目标,那就是成为社交游戏领域最大的公司。

他表示,未来几年内社交游戏将更为生活化和移动化,这样你就可以在5到15分钟的时间内获得如《魔兽世界》般的体验。

发布《CastleVille》

10月和11月末,股票市场依然波动剧烈。11月末,新的IPO机会显现,Yelp等公司申请IPO,Angie’s List成功上市。但是Zynga利用《CastleVille》打出漂亮的一拳,这款游戏的目标是将大型多人在线角色扮演游戏带到大众市场中。

2010年10月,Zynga购买了Bonfire Studios公司。这个公司中有大量曾经在微软Ensemble Studios(游戏邦注:《帝国时代》的开发商)中工作的经验丰富的开发者。在微软关闭Ensemble后,Bonfire诞生了。Zynga收购了这家公司,将其命名为Zynga Dallas。

Zynga Dallas创意总监Bill Jackson是前Ensemble雇员,他带领工作室开发这款游戏已1年有余。现在,Zynga Dallas发布的Ville系列游戏最新产品《CastleVille》已经成为Zynga旗下模拟游戏的骨干。这款游戏摒弃了Zynga常用的卡通风格,有着比以往更为有趣的游戏玩法。

Jackson说道:“《CastleVille》将Zynga的Ville系列产品提升到新层次。”

游戏的灵感来源于《怪物史莱克》之类的电影,但是其玩法风格却不同于市场上的任何其他产品。Zynga于11月14日发布这款游戏,当天便消除了《The Sims Social》对公司构成的巨大威胁。Zynga在Facebook的社交游戏市场份额约为40%,日活跃用户逾4500万,而EA只有1250万日活跃用户。

6天之后,《CastleVille》的用户量达到500万,将近68%的玩家每天玩两次游戏。《CastleVille》发布17天后,月活跃用户数量达到2080万。在《CityVille》发布整整1年后,《CastleVille》取代前者成为历史上成长速度最快的游戏。根据AppData统计数据显示,截止2011年12月12日,《CastleVille》拥有的月活跃用户数为3160万。这又是款轰动市场的游戏,足以让投资者感到高兴。而且,这只是公司旗下2号人物John Schappert所称的“公司历史上最活跃的发布时期”的首款游戏而已。

上市

回望2009,曾经有段时间Zynga除了良好的媒体形象外毫无收获。当时,Mark Pincus表示他本应该为《财富》、《福布斯》和《商业周刊》都报道公司正面形象而感到高兴,但是他却做不到。

他说道:“我本应该感到高兴,但是我却做不到。我觉得自己就像那个没穿衣服的皇帝。”

他认为,社交游戏和Zynga都有着巨大的潜力,但是离真正的成功还有很长一段路。

Pincus说道,当你面对即将到来的失败时,能做的最好的事情是在理智和情感上先接受失败。他说道:“这样,你知道自己可以控制自己的命运。”

但是到2011年,这种失败的威胁不再那么明显。

在今年IPO季度临近尾声之际,Zynga完成了细节的修改工作。Zynga表示截止9月30日,公司第3季度净收入为1250万美元,比去年同期下滑54%。盈利为3.07亿美元,与去年相比提升80%。彭博社报道称,Zynga将在感恩节后上市。此后,Zynga的命运将掌握在投资者手中。

竞争者对外公布Zynga对待雇员的负面做法。几乎在一瞬间,Mark Pincus又成了那个没穿衣服的皇帝。《华尔街日报》报道称,Zynga的Pincus逼迫表现不佳者退回他们的股票。11月17日,首席商务官Owen Van Natta辞职。《纽约时报》报道称,Zynga雇员对公司很不满,PopCap Games因担心Zynga的文化而拒绝了其9.5亿美元的收购出价,转而支持EA的7.5亿美元及5.5亿美元追加款项。据报道,Rovio也拒绝了Zynga伸出的24亿美元收购公司的橄榄枝。

但是,Zynga似乎并不担心这些负面的媒体报道。12月2日,公司提交募资多达10亿美元的计划,市值为89亿美元,每股价格从8.5美元增加至10美元。公司计划开展9天的路演来吸引投资者。股票在12月15日定价,12月16日开始交易。这是今年最后1次上市的机会,公司觉得要把握这次机会。

募集的资金数和市值比外界150亿到200亿美元的估计要低得多。更为糟糕的情况是,在公司的首轮资金募集中,市值比预定的更低,这意味着多数近期投资者要眼睁睁地看着他们在Zynga中投入的资金逐渐缩水。如果股价上涨到14美元每股,这些投资者兴许才会感到满意。

但是即便市值下滑,Zynga的市值依然比EA要高,尽管后者的盈利是前者的4倍,但是市值却只有70亿美元。Comcast Ventures合伙人Andrew Cleland回忆称,Pincus曾经告诉他Zynga的市值将在5年内超过EA。事实上,Pincus只花了几年时间就实现了这个目标。

Cleland估计,2012年Zynga将花5亿多美元来进行调研和开发,Pincus明年可能不会将公司主要目标定在盈利上。要实现公司的长期愿景,就必须要加大投入资金,而不是急于取得盈利。

Cleland写道:“该公司即将到来的IPO也是游戏行业的重要时刻,这意味着休闲和免费游戏引领西方游戏市场的时代已经来临。该公司路演的时间现在似乎已经确定了,对于Zynga的上市我们应当抱何期望呢?这个问题的答案可以反映出Pincus卓越的抱负,同时也暗示着投资者应当对公司抱何想法以及其他开发商应当如何统筹他们的上市战略。”

但是Cleland的看法似乎并不被投资者认同,欧洲经济危机和Zynga自身放缓的成长速度似乎吓住了投资者。Zynga要从哪里获取新用户,才能够使公司重新恢复竞争力?从7月到12月,公司市值从200亿下滑到100亿,其速度堪比Zynga当初的成长速度。现在,公司必须尽其所赢得投资者的尊重和信任。雇员之所以会产生不满的反应,部分原因就在于他们发现自己持有股份的价值已减半。

只要该公司开始为其投资者路演,Pincus就有机会向业界阐述Zynga有着光明未来的缘由。他表示,自己预期游戏领域的玩家数量能够在接下来的5年内从2011年的10亿增加到20亿。2011年应用下载量约为180亿次,5年内这个数量可能会增加4倍。2011年用户花费在虚拟商品上的金额数为90亿美元,5年内会增加2倍。

在手机市场方面,10月份Zynga拥有的日活跃用户数量为1110万,与1年前的99.1万相比大幅增加。公司目前在整体手机游戏市场中所占份额还很小,但是成长率是很可观的。Zynga在该领域的用户大部分来自于收购Newtoy,但是仍然存在发展的空间。

Zynga的广告盈利为5500万美元,与去年相比增加了162%。百思买之类的广告商都曾与公司合作,他们在《CityVille》中开展的活动使玩家在游戏中建造了800万个百思买商店。现在,广告盈利只占公司总盈利的5%,但是还在不断增加。这表明,公司还有着很大的盈利机遇。如果Zynga的2亿用户每人每月能够为公司带来1美元的广告盈利,那么年盈利就将达到24亿美元。

Wehner表示,广告盈利的优点在于,游戏发布很长时间后依然可以插入广告。《FarmVille》发布于2009年6月,但是Lady Gaga的赞助起始时间为2011年5月。因而,Zynga有大量通过广告来提升盈利的机遇。

在路演期间,Pincus表示Zynga或许也可以让公司旗下付费用户数量翻倍。现在,付费用户比例为2.5%,数量约为770万。让付费用户数量翻倍不是件简单的事情,但是如果Zynga可以实现的话,或许公司的盈利也有可能翻倍。

Michael Pachter(游戏邦注:他是专注于游戏和数字化媒体的Wedbush Securities调查分析师),他表示1到2年内有多种情况可能导致Zynga的付费用户数量翻倍。其中,两个关键的驱动因素便是Facebook和移动设备的发展。

Pachter说道,如果Facebook用户的数量增长到10亿,那么玩Zynga游戏的玩家数量自然也会随之增加。如果发生这种情况的话,即便Facebook中玩公司游戏的用户总比例保持不变,Zynga依然可以大致实现付费用户数翻倍的目标。

Zynga的John Schappert表示,公司会发布新游戏,进军新的国际市场,扩张到Google+、腾讯和Zynga.com等新平台上,同时增加公司在手机市场上的份额。

Schappert说道:“我们正在进入公司历史上最活跃的发布时期……我们相信,公司所选择的道路将成为娱乐行业中最强大的业务模型。”换句话说,如果你将Zynga视为投资产品,那么100亿美元的市值是其打折时期的价格,还有很大的增长空间。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

How Zynga grew from gaming outcast to $9 billion social game powerhouse

Dean Takahashi

Zynga has turned the video game world upside down in its short five-year history. As it’s poised on the verge of a massive initial public offering, the social game startup is now one of gaming’s great success stories.

But its success was never a foregone conclusion. In fact, most game industry veterans didn’t view it as a real game company. Mark Pincus was a four-time entrepreneur, but had no experience in the game industry and had never managed a big company. He was the most unlikely entrepreneur to create a game industry giant.

Now Pincus is poised to become a multibillionaire as the largest shareholder in a company that is about to hold on Thursday one of the biggest initial public offerings of the year. Zynga’s

billion-dollar IPO, at an $8.9 billion valuation, will be one of the biggest events in gaming history and will make it a financial peer to established rivals like Electronic Arts and Activision Blizzard. Through the IPO, Zynga hopes to meet the ambitious goal of investing more “in play than any company in history.”

And it is possible in no small part because Pincus, the gaming novice, dreamed bigger than the game industry when it came to giving users accessible and social games, anytime, anywhere. Against all odds, Zynga has out-competed big gaming brands in the great social game Gold Rush. Zynga games have continuously held the No. 1 ranked spot on Facebook since the beginning of 2009. As of today, it has five of the top five games on Facebook.

Pincus couldn’t have done it on his own. Along the way, he has been helped by the fortuitous friendship of gaming veteran Bing Gordon. Facebook insider Owen Van Natta played a key role at a critical time. And experienced game designers like Mark Skaggs and Brian Reynolds have led the creation of innovative, addictive games, helping the company rise above its early reputation as a creator of cheap knockoffs and a persistent spammer of Facebook news feeds. Together, these people helped Zynga get where it is today, while rivals like Playfish and Playdom decided to take earlier, less lucrative exits.

Since its inception in 2007, Zynga has generated more than $1.5 billion in revenues — a remarkable sum for such a young company. It is now trying to seize the leading share of a $9 billion virtual goods market that it believes could triple in the next five years.

Now the company’s ambition is to become as synonymous with play on the internet as Google is with search, Amazon is with shopping, and Facebook is with sharing. It was lucky that Zynga started out with so little game experience in the beginning. But throughout its life, it would have to prove over and over again that it was a real game company that mattered.

In the following pages, I’ll tell the tale of Zynga from its earliest days. This story is based on extensive interviews and research since 2008. We’ve had limited access to Mark Pincus. In recent months, he hasn’t been giving interviews, due to a quiet period mandated by regulators. But the story of Zynga isn’t just about the founder of the company. It’s also about the whole cast of characters who surrounded him, the rivals who drove him to succeed, and the industry that challenged Zynga to prove itself over and over. We’ve done our best to triangulate on how Zynga became what it is today — and how it almost didn’t happen.

Humble beginnings

“I had a lot of careers before I became an entrepreneur,” Pincus said in a speech about starting companies at Startup Berkeley in the spring of 2009. “And I failed on other people’s money. If you were trying to become a professional athlete, you would want to go through junior leagues first before you started a pro circuit. Fail a lot before you are paying for the failure….I got fired or asked to leave from all my jobs.”

The option that was left for him, Pincus joked, was to become an entrepreneur. He had read George Gilder’s book, Microcosm, and was excited about the economics of the world enabled by technology.

That drove him into new media. He eventually made his way to Silicon Valley, starting FreeLoader, a web-based push company, in 1995 with a $250,000 loan. That company was acquired after seven months for $38 million by Individual. It was the start of Web 1.0, or the first giant wave of the first real internet companies.

At the time, other tech companies were selling out for hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars, making Pincus’ exit look almost paltry. Still, his first startup success gave Pincus a full membership in Silicon Valley’s dot-com era. He then founded Support.com (later SupportSoft), a provider of service and support automation software, along with Cadir Lee and Scott Dale. The company went public in July 2000.

Flush with cash, Pincus co-founded his own incubator, Tank Hill in January, 2000. It was just in time for the dot-com crash, and he and his partner shut it down and returned the funds nine months later. In 2003, at the age of 37, he started Tribe.net, one of the first social networks. Pincus thought of it as a “Craigslist meets Friendster.” That didn’t work out so well. Pincus left in 2005, after the board threw him out. In 2006, he took it back over from the investors and sold its assets to Cisco. At the time, Tribe.net had just eight employees, and Cisco completed its purchase by March 2007.

He teamed up with his friend Reid Hoffman, a PayPal veteran and now founder of LinkedIn, to buy a patent on social networking from the defunct Sixdegrees for $700,000. Then they invested in a little company called Facebook, which turned out to be at the beginning of the Web 2.0 wave of companies, or those that were built to take advantage of a newly dynamic web and its growing network of interconnected users. That put Pincus in close touch with Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and gave him the inside track to the social media revolution.

Pincus is on record as starting four companies, but he said there were 15 or 20 projects that failed. But Pincus did have a nice touch as an angel investor. His investments included Napster, eGroups, Technorati, Socialtext, Friendster, Ireit, Nanosolar, Merlin, Naseeb, EZboard, Advent Solar, Xoom — and Facebook. Noticeably absent from that list were any game companies.

Making the right bet

To get to Zynga, Pincus said he had three formal failures, including Tribe.net. Another failure was an ad company called Tag Sense. From that, he concluded, “Don’t go start a company just because you have a customer and someone will fund you. If it is a marginal idea, that’s bad.”

Because Tag Sense failed quickly, Pincus said, he was ready when, in the May 2007, Facebook opened up its applications programming interface, inviting other companies to make applications on top of its social network in hopes of beating MySpace. That move helped Facebook gain users as well as developers, creating a virtuous circle. Pincus decided to go along for the ride.

Previously, Pincus had been operating under the name Presidio Media, a company which he formed in April, 2007, as part of an effort to jump on the Facebook bandwagon.

“The whole time I was doing Tribe, I thought the thing I would have loved to do is games,” Pincus said in a 2009 interview:

I’ve always said that social games are like a great cocktail party: You’re happy at first to see your good friends, but the value of the cocktail party is in the weak ties. It’s the people you wouldn’t have thought of meeting; it’s the friends of the friends….What I thought was the ultimate thing you can do — once you bring all of your friends and their friends together — is play games. I’ve always been a closet gamer, but I never have the time and can never get all of my friends together in one place. So the power of my friends already being there and connected, and then adding games, seemed like a big idea.

In July 2007, Pincus changed the name of his new company to Zynga, named after his late bulldog, Zinga. Zynga’s first headquarters were in the Chip Factory in the Potrero Hill neighborhood in San Francisco.

From his previous experiences, Pincus learned, “Control your destiny. We all write this story for ourselves that we were really successful and the evil VC came in and f***** up our company. They backed us and got rid of us and if they had just left us alone. That’s everybody’s sob story in Silicon Valley. You f****** it up because you gave them control of it.” He said he would settle for half the valuation if he could control his company and destiny. As a result of that desire, he funded Zynga himself.

The early team included Eric Schiermeyer, Michael Luxton, Justin Waldron, Kyle Stewart, Scott Dale, Steve Schoettler, Kevin Hagan, and Andrew Trader. Pincus was intense and drove them hard, but he wanted to build a great company.

Its first successes were on MySpace, where other social game companies were making money from ad-based games. Zynga’s early revenue came from MySpace, but Pincus had the smarts to realize that Facebook would win in the future. It was a smart bet that helped Zynga to catch Facebook’s coattails as it went through an unprecedented wave of growth.

As he tried out ideas, he kept in mind that he should test them as cheaply and as quickly as he could.

The company released its first game for Facebook in September 2007. It created a free social poker game on Facebook, chosen because it was simple and it was a universal game that enabled friends to plan a “poker night” with each other no matter if they were far apart or not. Zynga was riding a wave of resurgence that poker had seen since 2003. Zynga’s first game was successful enough to make the company profitable.

“We were the first company to believe in the social gaming opportunity and go after it with our poker game in July, 2007,” Pincus said in an interview with VentureBeat in 2009. “Everybody else was focused on viral apps like pokes and other things that spread more virally. We were always interested in just the gaming opportunity. By the time we saw it was real and had a sustainable revenue stream, we were the first to start investing deeply in it.”

Before Zynga, free games were often viewed as low-quality shareware. But now they were something that millions of people could enjoy. The poker game gained users for a while, but it had no real monetization beyond ads at first. Eventually, in March 2008, Zynga added a way to sell poker chips via “lead generation,” where a user could get chips if they participated in a revenue-generating activity for Zynga, such as accepting an offer to sign up for something.

In a poor choice of words that would eventually come back to haunt him, Pincus later said in his Berkeley speech that “I did every horrible thing in the book to just get revenues right away.” He said that Zynga gave users poker chips in its first game, Texas Hold ‘Em Poker, if they would download a Wiki tool that was difficult or impossible to remove.

In mid-2008, Zynga launched Mafia Wars, its second game, and it acquired another game called YoVille. The Mafia Wars game was available on both Facebook and MySpace, because it wasn’t clear which social network was going to be the winner yet.

In the process of launching its games, Zynga would hit upon some unique ideas that it would later describe as its philosophy. It believed games should be accessible to everyone, anywhere, any time.

Games should be social. Games should be free. Games should be data driven. And games should do good. Those were lofty goals, but no one else in the industry believed in trying to make all of those things happen.

Pincus’s intent was to create a real business before he needed to go into a venture capitalist’s office. By the time Zynga raised its first round of money, it had generated only $693,000 in revenue in 2007, but it had a path to growth because its user count was growing fast, and it was already profitable. As a result, Pincus was able to command unusual terms, like giving himself stock that had 10 times the votes of common shares and maintaining control of his board of directors.

He was also able to secure investors that he was already friends with. In a deal announced Jan. 15, 2008, Zynga was able to raise $5 million from Union Square Ventures, Foundry Group, Avalon Ventures, Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel and other angels.

With the new money, Zynga was able to move even faster at a time when the great Facebook land rush was under way. The social network constantly revamped its platform and app makers had to adjust in real-time. Pincus called this “organic development,” where the company’s own internal developers had to pay close attention to Facebook and redo their work every 90 days or so.

The business would be metric-driven, combining intuition and data. The would enable the business to rapidly iterate and drive reach, retention and revenue. That is exactly how Zynga put distance between itself and others; it learned what users wanted and modified its games quickly, sometimes overnight, to better provide what the users wanted. Zynga started testing every idea. Web 2.0 companies behaved in this fashion, but game companies for the most part didn’t.

But it was true the company forever be at the mercy of the rules that Facebook made.

“Does it bother us that we’re a fly on Facebook’s ass?” Pincus joked in his talk. “In 2007, people laughed at me” for doing a Facebook app company. “We live and die by the changes these guys make.”

Data also could be a game designer’s enemy. If a game didn’t take off, Pincus had no qualms about killing it. He spent $3 million developing an unnamed role-playing game. But the title didn’t take off in a viral way when it launched, so Pincus pulled the plug on it. Pincus became ruthless about canceling games that weren’t working.

Zynga was growing fast thanks to Mafia Wars and Zynga Poker, and it was making money. And Facebook was still growing like crazy.

At the time, the speed was important. Not everyone realized it, but Zynga was in a monumental race to beat others to the treasure. If it learned the most about how to make money from social games and executed the fastest, it would own the market, regardless of whether giant companies came into it later.

So just a few months after its first round, Zynga raised another, larger pile of cash.

In July 2008, the world took notice as Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers invested $29 million in Zynga. Bing Gordon (pictured above), the former chief creative officer at Electronic Arts and now a partner at Kleiner, joined Zynga’s board. Mark Pincus welcomed him as a key advisor.

The amount of money was huge for a gaming startup at the time. Few other companies had amassed such a large amount. It meant that Zynga was always going to have a pile of money to invest in its next major titles. That was a luxury that many of its competitors didn’t have, and it was why they fell behind.

Later on, Pincus said that one of the lessons of failure was to surround himself with people that he could learn from. Gordon was such a mentor. While Pincus had the Web 2.0 experience, Gordon knew games. He was able to put Pincus in touch with large number of job candidates in the game industry who were willing to try something new. Some of them, like veteran game designer Mark Skaggs, came from Electronic Arts. He joined as a top game exec at Zynga in November 2008. Skaggs would go on to lead some of the most important games that the company would create.

“I’m a consigliere,” Gordon said in an interview with VentureBeat in the fall of 2010, referring to the Robert Duvall character in The Godfather movie. “I have my own assignments now and then.

I have done more recruiting than Robert Duvall. But I have high regard for Mark Pincus as a visionary. He combined the best of the web, games, and social. It never occurred to anyone those would come together.”

Gordon showed up at the company all of the time, lending his advice and bringing in new people as they were needed.

Recruiting talent

John Doerr and Bing Gordon

During this time, everything was moving fast. As Zynga expanded, it was able to bring on game talent in part because there was a recession that was killing off a lot of console game studios. Bing Gordon’s presence on the board of Zynga — and his regular presence at the company — gave the company better credibility.

Gordon knew what Zynga’s reputation was like and he tried hard to contain some of that damage. According to papers obtained by the SF Weekly, Gordon wrote a confidential memo to his partners at Kleiner Perkins.

It said, “Mark needs strong lieutenants to keep him from micromanaging.” Gordon suggested that he and another top executive play strong roles in the company to offset Pincus’s style. “Bing to temper Mark, and bring on board a billion-dollar game industry COO when Zynga gets to about $100 million.” The memo also warned that Zynga was overly reliant on Facebook.

But Pincus lasted far longer than anyone thought, given that he was running a game company. And he did so by finding talent wherever he could. He didn’t wait for the game developers to come to him.

Sometimes, Pincus found technical experts and asked them to become game makers. Justin Cinicolo, a mid-20s Carnegie Mellon University grad with a few years of work experience, decided to check out Zynga because his roommate got a job there and was coming home with a smile on his face. Cinicolo also joined early and was so thrilled at the fast pace and energy that he recruited another dozen Carnegie Mellon friends to join.

What Cinicolo found was that Zynga tried to live up to what it would later codify as core values. The company told its people to “build the games you and your friends love to play,” “Zynga is a meritocracy,” “Be a CEO and own outcomes,” “Move at Zynga speed,” “Put Zynga first, decisions for the greater good,” and “Always innovate.” Some might find that laughable, but Cinicolo could see the truth in it.

The idea of being a CEO resonated with Cinicolo, and it came from Pincus himself. Pincus recalled that, at his second company, he put some sheets on a wall and wrote everyone’s name on it. “By the end of the week, everyone needs to write what you’re CEO of, and it needs to be something really meaningful…. People liked it. And there was nowhere to hide,” Pincus said.

Cinicolo was installed as a producer on Mafia Wars after the game launched. His job was to keep it growing and to beat its competition.

In analyzing the game, he had to rely on tools from Cadir Lee, who had co-founded two other companies with Pincus and had joined Zynga when it had around 100 employees, in November 2008. At the time, Lee’s mission was to build the greatest data warehouse in the entire game industry.

Lee’s first job was to build a dashboard for analytics, taking it from a bunch of numbers to a user interface that could show producers like Cinicolo everything they needed to know about a game. They could do A/B testing, or test to see if gamers like a pink message better than a blue message. When the results came back, it was easy to decide which worked better and the company could learn such lessons at an extremely fast pace.

“We built analytics from zero to a competitive differentiator,” Lee said in an interview with VentureBeat in the fall of 2010. “We have a mass of infrastructure, analysis, and statisticians. It is the lifeblood of Zynga.”

Benjamin Joffe, chief executive of social game maker Cmune, said that Zynga made analytics into a science and operated on the principle of “do more of what works.”

That was another thing that traditional game developers hated. They wanted to design their games by intuition and craftsmanship, not popular vote. But some of them saw the logic of it. Normally, developers would work for two to five years on a console game and then find out on launch day if the gamers really liked it. With Zynga, a developer could create code that millions of players would see the next day. The feedback was immediate.

With analytics tools, it was a lot easier for Cinicolo to take the Mafia Wars game and boost it. Four months after it launched, it had around 100,000 users. Cinicolo’s goal was to boost it to a million. When he hit that, his boss Eric Shiermeyer asked him to take it to 2 million. In 2008, Mafia Wars generated 20 percent of Zynga’s revenue. The next year, Mafia Wars grew dramatically and it contributed $32 million in revenue in 2009 and $161 million in revenue in 2010. Mafia Wars still has about 6 million monthly active users.

“I went from project to project, with a ragtag group,” Cinicolo said in an interview in the fall of 2010. “I was creatively very energized. If stuff breaks, we fix it.”

Depending on the project, Cinicolo worked with Mark Pincus on a weekly or a daily basis, soliciting ideas from his boss on how to make the games better. The team would stick around for free dinners and drink beer as they talked about where to go next. By 2010, he transferred over to the mobile game frontier.

“Pincus acts like a partner,” Cinicolo said. “He’s never really a boss. He collaborates. In some ways, he has changed. He has gotten calmer. He is super-energetic and as passionate as ever. But he is more willing to do things like mobile where we know it will take some time before it becomes as successful as the web business.”

At age 28, in the fall of 2010, Cinicolo was in charge of a number of major mobile game efforts as general manager of mobility.

By the end of 2008, Maestri settled his lawsuit with SGN and won the rights to Mob Wars. Then, in September 2009, he settled with Zynga, which agreed to pay him $7 million to $9 million. By that time, Zynga had its own bone to pick with Playdom, which Zynga accused of hiring its employees in order to copy its games and steal its “playbook” for making popular games.

The making of FarmVille

In the spring of 2009, a small developer called Slashkey created a game called Farm Town. It was a simple farming game, not much different from farm games in China or the old Harvest Moon games on the consoles. All it did was enable users to simulate the life and growth of a farm. With only viral word-of-mouth for marketing, the game spread like wildfire, adding 300,000 users a day. Within a matter of a couple of months, it had more than 14 million registered users on Facebook.

It seemed like FarmVille was an obvious copycat, but the game’s origins are a little murky. Mark Skaggs, the former Electronic Arts game designer at Zynga, said the idea for a new title came from Bing Gordon, the Kleiner Perkins partner and Zynga board member. One day, he put his feet up on the desk and asked, “Why don’t you make a farm game?” It was a sentiment that Mark Pincus shared.

Skaggs was one of the instrumental early game designers at Zynga. He had been in charge of a variety of PC games that had sold more than 16 million copies at Electronic Arts, from Command and Conquer Generals to Lord of the Rings Battle for Middle-Earth. He spent seven years at EA, after the 1998 acquisition of Westwood Studios. He left EA in 2005 to co-found Trilogy Studios, which was making a massively multiplayer online game. That didn’t work out, so Bing Gordon suggested that he give Zynga a try. He joined early enough to have a lot of influence with the way Zynga designed its games.

Unfortunately, Zynga didn’t have a full team available. Skaggs had to look on the outside. Zynga was in talks to buy MyMiniLife, which had a few employees and a game engine that could be used for the farm game. Between Zynga and MyMiniLife, the team grew to nine people. They worked for five weeks to get the job done. Some of that work was done before Zynga had acquired MyMiniLife, which included Sizhao Yang, Amitt Mahajan, Luke Rajlich, and Joel Poloney.

MyMiniLife was started in 2007 as a social network and it grew to 4 million users. The company was working on a game engine for running Flash-based games on a social network. This was a tough thing to do, as Flash games could run notoriously slow, particularly if they weren’t customized properly. The engine was working well enough that it could be easily modified to run different games.

But MyMiniLife struggled to retain users. Max Levchin of Slide made the first acquisition offer, followed by Zynga, Hi5 and Challenge Games. Zynga wined and dined the team and kept raising the bid. Mark Pincus spent a lot of time working on the deal, which was closed on June 5, 2009 for an undisclosed price. It was one of those times when Pincus had acted very decisively on just a little bit of information. He used his instincts and drove his team in the right direction to get the deal done.

MyMiniLife had built a stable platform that could handle lots of users. Without it, scaling would have been an issue.

The production team moved so fast that they stole the avatars, or virtual characters, from Zynga’s YoVille game. Mothers using Facebook to monitor their kids’ activities or stay in touch with old friends were the primary target. Besides Skaggs and the MyMiniLife team, others who worked on FarmVille included Raymond Holmes, Sifang Lu, David Gray, and Craig Woida.

On June 19, 2009, Zynga launched its Farm Town clone, FarmVille. With the a production cycle of only five weeks, the game grew at an unprecedented rate. Unlike its rivals, Zynga started spending lots of money on ads on social networks. Within two months, Zynga’s FarmVille had 5 million users. Pincus pulled resources from other projects to support FarmVille’s growth.

Meanwhile, Farm Town was hitting growth pains. By contrast, Zynga hit a million players within four or five days. It already had millions of users and was tapping the outside computer services of Amazon, whose Amazon Web Services division was farming out data centers that the company didn’t need for its core electronic commerce business.

All of that computing power gave Zynga a lot of insight. Cadir Lee, chief technology officer, said in an interview in the fall of 2010 that Zynga could mine its data because it was a web company.

“We get data within 5 minutes of something happening,” he said. “Metrics and watching data is a part of the culture. Web companies do a lot of analysis. You have this virtual world where you track everything that happens, like how many plots of super berries there are.”

Asked if FarmVille beat Farm Town because of Zynga’s better web infrastructure, Lee said, “That’s a fair representation.”

With Amazon, Zynga was about to scale its web servers up or down as it needed. It was much more prepared for hyper growth with a game than a smaller rival such as Slashkey.

“We solved a lot of tech problems for FarmVille,” Lee said. “We had some days where servers were on the edge of blowing up and we would release a new technology that gave us more head room. We learned what scaled way, and later on we would really shift the way we built our games. We found it was not the amount of hardware that mattered. It was the architecture of the application. We had to build it in a way that took advantage of Amazon.”

The MyMiniLife engine proved to be a competitive differentiator and it was used again in every Zynga game from FrontierVille on. It was one of the secrets behind Zynga’s success, as other companies made Flash-based games that took to long to load or just ran unacceptably slow.

Once again, traditional game designers looked down on Zynga’s “game.”

Ian Bogost, the Georgia Tech professor, was so disgusted with FarmVille’s lack of game play that he created a parody called “Cow Clicker,” where all you did was click on cows. It would take a long time for Zynga to escape that kind of criticism.