Understanding JVM Internals---不得不转载呀

http://www.cubrid.org/blog/dev-platform/understanding-jvm-internals/

http://architects.dzone.com/articles/understanding-jvm-internals 这篇也不错,推荐读一下

Every developer who uses Java knows that Java bytecode runs in a JRE (Java Runtime Environment). The most important element of the JRE is Java Virtual Machine (JVM), which analyzes and executes Java byte code. Java developers do not need to know how JVM works. So many great applications and libraries have already been developed without developers understanding JVM deeply. However, if you understand JVM, you will understand Java more, and will be able to solve the problems which seem to be so simple but unsolvable.

Thus, in this article I will explain how JVM works, its structure, how it executes Java bytecode, the order of execution, examples of common mistakes and their solutions, as well as the new features in Java SE 7 Edition.

Virtual Machine

The JRE is composed of the Java API and the JVM. The role of the JVM is to read the Java application through the Class Loader and execute it along with the Java API.

A virtual machine (VM) is a software implementation of a machine (i.e. a computer) that executes programs like a physical machine. Originally, Java was designed to run based on a virtual machine separated from a physical machine for implementing WORA (Write Once Run Anywhere), although this goal has been mostly forgotten. Therefore, the JVM runs on all kinds of hardware to execute the Java Bytecode without changing the Java execution code.

The features of JVM are as follows:

- Stack-based virtual machine: The most popular computer architectures such as Intel x86 Architecture and ARM Architecture run based on a register. However, JVM runs based on a stack.

- Symbolic reference: All types (class and interface) except for primitive data types are referred to through symbolic reference, instead of through explicit memory address-based reference.

- Garbage collection: A class instance is explicitly created by the user code and automatically destroyed by garbage collection.

- Guarantees platform independence by clearly defining the primitive data type: A traditional language such as C/C++ has different int type size according to the platform. The JVM clearly defines the primitive data type to maintain its compatibility and guarantee platform independence.

- Network byte order: The Java class file uses the network byte order. To maintain platform independence between the little endian used by Intel x86 Architecture and the big endian used by the RISC Series Architecture, a fixed byte order must be kept. Therefore, JVM uses the network byte order, which is used for network transfer. The network byte order is the big endian.

Sun Microsystems developed Java. However, any vendor can develop and provide a JVM by following the Java Virtual Machine Specification. For this reason, there are various JVMs, including Oracle Hotspot JVM and IBM JVM. The Dalvik VM in Google's Android operating system is a kind of JVM, though it does not follow the Java Virtual Machine Specification. Unlike Java VMs, which are stack machines, the Dalvik VM is a register-based architecture. Java bytecode is also converted into an register-based instruction set used by the Dalvik VM.

Java bytecode

To implement WORA, the JVM uses Java bytecode, a middle-language between Java (user language) and the machine language. This Java bytecode is the smallest unit that deploys the Java code.

Before explaining the Java bytecode, let's take a look at it. This case is a summary of a real example that has occurred in development process.

Symptom

An application that had been running successfully no longer runs. Moreover, returns the following error after the library has been updated.

|

1

2

3

|

Exception in thread

"main"

java.lang.NoSuchMethodError: com.nhn.user.UserAdmin.addUser(Ljava/lang/String;)V

at com.nhn.service.UserService.add(UserService.java:

14

)

at com.nhn.service.UserService.main(UserService.java:

19

)

|

The application code is as follows, and no changes to it have been made.

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

// UserService.java

…

public

void

add(String userName) {

admin.addUser(userName);

}

|

The updated library source code and the original source code are as follows.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

|

// UserAdmin.java - Updated library source code

…

public

User addUser(String userName) {

User user =

new

User(userName);

User prevUser = userMap.put(userName, user);

return

prevUser;

}

// UserAdmin.java - Original library source code

…

public

void

addUser(String userName) {

User user =

new

User(userName);

userMap.put(userName, user);

}

|

In short, the addUser() method which has no return value has been changed to a method that returns the User class instance. However, the application code has not been changed, since it does not use the return value of the addUser() method.

At first glance, the com.nhn.user.UserAdmin.addUser() method seems to still exist, but if so, why does NoSuchMethodError occur?

Reasons

The reason is that the application code has not been compiled to a new library. In other words, the application code seems to invoke methods regardless of the return value. However, the compiled class file indicates the method that has a return value.

You will see this through the following error message.

|

1

|

java.lang.NoSuchMethodError: com.nhn.user.UserAdmin.addUser(Ljava/lang/String;)V

|

NoSuchMethodError has occurred since the "com.nhn.user.UserAdmin.addUser(Ljava/lang/String;)V" method could not be found. Take a look at "Ljava/lang/String;" and the last "V". In the expression of Java Bytecode,"L<classname>;" is the class instance. This means that the addUser() method returns one java/lang/String object as a parameter. In the library of this case, the parameter has not been changed, so it is normal. The last"V" of the message stands for the return value of the method. In the expression of Java Bytecode, "V" means that it has no return value. In short, the error message means that one java.lang.String object has been returned as a parameter and the com.nhn.user.UserAdmin.addUser method without any return value has not been found.

Since the application code has been compiled to the previous library, the class file defined that a method that returns "V" should be invoked. However, in the changed library, the method that returned "V" did not exist, but the method that returned "Lcom/nhn/user/User;" has been added. Therefore, a NoSuchMethodError occurred.

Note

The error has occurred since the developer did not compile a new library again. However, in this case, the library provider is mostly responsible for that. There was no return value of the method as public, but it later has been changed to return the user class instance. This is an obvious method signature change. This means that the backward compatibility of the library has been broken. Therefore, the library provider must have reported to the users that the method has been changed.

Let's go back to the Java Bytecode. Java Bytecode is the essential element of JVM. The JVM is an emulator that emulates the Java Bytecode. Java compiler does not directly convert high-level language such as C/C++ to the machine language (direct CPU instruction); it converts the Java language that the developer understands to the Java Bytecode that the JVM understands. Since Java bytecode has no platform-dependent code, it is executable on the hardware where the JVM (accurately, the JRE of the same profile) has been installed, even when the CPU or OS is different (a class file developed and compiled on the Windows PC can be executed on the Linux machine without additional change.) The size of the compiled code is almost identical to the size of the source code, making it easy to transfer and execute the compiled code via the network.

The class file itself is a binary file that cannot be understood by a human. To manage this file, JVM vendors provide javap, the disassembler. The result of using javap is called Java assembly. In the above case, the Java assembly below is obtained by disassembling the UserService.add() method of the application code with the javap -c option.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

|

public

void

add(java.lang.String);

Code:

0

: aload_0

1

: getfield #

15

;

//Field admin:Lcom/nhn/user/UserAdmin;

4

: aload_1

5

: invokevirtual #

23

;

//Method com/nhn/user/UserAdmin.addUser:(Ljava/lang/String;)V

8

:

return

|

In this Java assembly, the addUser() method is invoked by the fourth row, "5: invokevirtual #23;". This means that the method corresponding to the 23rd index should be invoked. The method of the 23rd index is annotated by the javap program. The invokevirtual is the OpCode (operation code) of the most basic command that invokes a method in the Java Bytecode. For reference, there are four OpCodes that invoke a method in the Java Bytecode: invokeinterface, invokespecial, invokestatic, and invokevirtual. The meaning of each OpCode is as follows.

- invokeinterface: Invokes an interface method

- invokespecial: Invokes an initializer, private method, or superclass method

- invokestatic: Invokes static methods

- invokevirtual: Invokes instance methods

The instruction set of Java Bytecode consists of OpCode and Operand. The OpCode such as invokevirtual requires a 2-byte Operand.

By compiling the application code above with the updated library and then disassembling it, the following result will be obtained.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

public

void

add(java.lang.String);

Code:

0

: aload_0

1

: getfield #

15

;

//Field admin:Lcom/nhn/user/UserAdmin;

4

: aload_1

5

: invokevirtual #

23

;

//Method com/nhn/user/UserAdmin.addUser:(Ljava/lang/String;)Lcom/nhn/user/User;

8

: pop

9

:

return

|

You can see that the method corresponding to the 23rd has been converted to the method that returns "Lcom/nhn/user/User;".

In the disassembled result above, what does the number in front of the code mean?

It is the byte number. Perhaps this is the reason why the code executed by the JVM is called Java "Byte"code. In short, the bytecode instruction OpCodes such as aload_0, getfield, and invokevirtual are expressed as a 1-byte byte number. (aload_0 = 0x2a, getfield = 0xb4, invokevirtual = 0xb6) Therefore, the maximum number of Java Bytecode instruction OpCodes is 256.

OpCodes such as aload_0 and aload_1 do not need any Operand. Therefore, the next byte of aload_0 is the OpCode of the next instruction. However, getfield and invokevirtual need the 2-byte Operand. Therefore, the next instruction of getfield on the first byte is written on the fourth byte by skipping two bytes. The bytecode shown through Hex Editor is as follows.

|

1

|

2a b4

00

0f 2b b6

00

17

57

b1

|

In the Java Bytecode, the class instance is expressed as "L;" and void is expressed as "V". In this way, other types have their own expressions. The table below summarizes the expressions.

TABLE 1: TYPE EXPRESSION IN JAVA BYTECODE

| Java Bytecode | Type | Description |

| B | byte | signed byte |

| C | char | Unicode character |

| D | double | double-precision floating-point value |

| F | float | single-precision floating-point value |

| I | int | integer |

| J | long | long integer |

| L<classname> | reference | an instance of class <classname> |

| S | short | signed short |

| Z | boolean | true or false |

| [ | reference | one array dimension |

The table below shows examples of Java Bytecode expressions.

TABLE 2: EXAMPLES OF JAVA BYTECODE EXPRESSIONS

| Java Code | Java Bytecode Expression |

| double d[][][]; | [[[D |

| Object mymethod(int I, double d, Thread t) | (IDLjava/lang/Thread;)Ljava/lang/Object; |

For more details, see "4.3 Descriptors" in "The Java Virtual Machine Specification, Second Edition". For various Java Bytecode instruction sets, see "6. The Java Virtual Machine Instruction Set" in "The Java Virtual Machine Specification, Second Edition".

Class File Format

Before explaining the Java class file format, let's review an example that frequently occurs in Java Web applications.

Symptom

When writing and executing JSP on Tomcat, the JSP did not run, and the following error occurred.

|

1

2

|

Servlet.service()

for

servlet jsp threw exception org.apache.jasper.JasperException: Unable to compile

class

for

JSP Generated servlet error:

The code of method _jspService(HttpServletRequest, HttpServletResponse) is exceeding the

65535

bytes limit"

|

Reasons

The error message above varies slightly depending on the Web application server, however, one thing is the same; it is because of the 65535 byte limit. The 65535 byte limit is one of the JVM limitations, and stipulates that the size of one method cannot be more than 65535 bytes.

I will present the meaning of the 65535 byte limit and why it has been set in more detailed manner.

The branch/jump instructions used in the Java Bytecode are "goto" and "jsr".

|

1

2

|

goto

[branchbyte1] [branchbyte2]

jsr [branchbyte1] [branchbyte2]

|

Both of the two receive 2-byte signed branch offset as their Operand so that they can be expanded to the 65535th index at a maximum. However, to support more sufficient branch, Java Bytecode prepares "goto_w" and "jsr_w" that receive 4-byte signed branch offset.

|

1

2

|

goto_w [branchbyte1] [branchbyte2] [branchbyte3] [branchbyte4]

jsr_w [branchbyte1] [branchbyte2] [branchbyte3] [branchbyte4]

|

With the two, branch is available with an index exceeding 65535. Therefore, the 65535 byte limit of Java method may be overcome. However, due to various other limits of the Java class file format, the Java method still cannot exceed 65535 bytes. To view other limits, I will simply explain the class file format.

The outline of a Java class file is as follows:

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

ClassFile {

u4 magic;

u2 minor_version;

u2 major_version;

u2 constant_pool_count;

cp_info constant_pool[constant_pool_count-

1

];

u2 access_flags;

u2 this_class;

u2 super_class;

u2 interfaces_count;

u2 interfaces[interfaces_count];

u2 fields_count;

field_info fields[fields_count];

u2 methods_count;

method_info methods[methods_count];

u2 attributes_count;

attribute_info attributes[attributes_count];}

|

The above is included in "4.1. The ClassFile Structure" of "The Java Virtual Machine Specification, Second Edition".

The first 16 bytes of the UserService.class file disassembled earlier are shown as follows in the Hex Editor.

ca fe ba be 00 00 00 32 00 28 07 00 02 01 00 1b

With this value, see the class file format.

- magic: The first 4 bytes of the class file are the magic number. This is a pre-specified value to distinguish the Java class file. As shown in the Hex Editor above, the value is always 0xCAFEBABE. In short, when the first 4 bytes of a file is 0xCAFEBABE, it can be regarded as the Java class file. This is a kind of "witty" magic number related to the name "Java".

- minor_version, major_version: The next 4 bytes indicate the class version. As the UserService.class file is 0x00000032, the class version is 50.0. The version of a class file compiled by JDK 1.6 is 50.0, and the version of a class file compiled by JDK 1.5 is 49.0. The JVM must maintain backward compatibility with class files compiled in a lower version than itself. On the other hand, when a upper-version class file is executed in the lower-version JVM, java.lang.UnsupportedClassVersionError occurs.

- constant_pool_count, constant_pool[]: Next to the version, the class-type constant pool information is described. This is the information included in the Runtime Constant Pool area, which will be explained later. While loading the class file, the JVM includes the constant_pool information in the Runtime Constant Pool area of the method area. As the constant_pool_count of the UserService.class file is 0x0028, you can see that the constant_pool has (40-1) indexes, 39 indexes.

- access_flags: This is the flag that shows the modifier information of a class; in other words, it shows public, final, abstract or whether or not to interface.

- this_class, super_class: The index in the constant_pool for the class corresponding to this and super, respectively.

- interfaces_count, interfaces[]: The index in the the constant_pool for the number of interfaces implemented by the class and each interface.

- fields_count, fields[]: The number of fields and the field information of the class. The field information includes the field name, type information, modifier, and index in the constant_pool.

- methods_count, methods[]: The number of methods in a class and the methods information of the class. The methods information includes the methods name, type and number of the parameters, return type, modifier, index in the constant_pool, execution code of the method, and exception information.

- attributes_count, attributes[]: The attribute_info structure has various attributes. For field_info or method_info, attribute_info is used.

The javap program briefly shows the class file format in a format that users can read. When UserService.class is analyzed using the "javap -verbose" option, the following contents are printed.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

|

Compiled from

"UserService.java"

public

class

com.nhn.service.UserService

extends

java.lang.Object

SourceFile:

"UserService.java"

minor version:

0

major version:

50

Constant pool:

const

#

1

=

class

#

2

;

// com/nhn/service/UserService

const

#

2

= Asciz com/nhn/service/UserService;

const

#

3

=

class

#

4

;

// java/lang/Object

const

#

4

= Asciz java/lang/Object;

const

#

5

= Asciz admin;

const

#

6

= Asciz Lcom/nhn/user/UserAdmin;;

// … omitted - constant pool continued …

{

// … omitted - method information …

public

void

add(java.lang.String);

Code:

Stack=

2

, Locals=

2

, Args_size=

2

0

: aload_0

1

: getfield #

15

;

//Field admin:Lcom/nhn/user/UserAdmin;

4

: aload_1

5

: invokevirtual #

23

;

//Method com/nhn/user/UserAdmin.addUser:(Ljava/lang/String;)Lcom/nhn/user/User;

8

: pop

9

:

return

LineNumberTable:

line

14

:

0

line

15

:

9

LocalVariableTable:

Start Length Slot Name Signature

0

10

0

this

Lcom/nhn/service/UserService;

0

10

1

userName Ljava/lang/String;

// … Omitted - Other method information …

}

|

Due to a lack of space, I have extracted some parts from the entire printout. The entire printout shows you the various information included in the constant pool and the contents of each method.

The 65535 byte limit of method size is related to the contents of method_info struct. The method_info struct has Code, LineNumberTable, and LocalVariableTable attribute, as shown in the "javap -verbose" print shown above. All of the values corresponding to the length of LineNumberTable, LocalVariableTable, and exception_table included in the Code attribute are fixed at 2 bytes. Therefore, the method size cannot exceed the length of LineNumberTable, LocalVariableTable, and exception_table, and is limited to 65535 bytes.

Many people have complaints about the method size limit, and the JVM specifications state that 'it may be expandable later.’ However, no explicit move toward improvement has been made so far. Considering the characteristic of JVM specifications that loads almost same contents in the class file to the method area, it will be significantly difficult to expand the method size while maintining backward compatibility.

What will happen if an incorrect class file is created because of a Java compiler error? Or, what if due to errors in network transfer or file copy process, a class file can be broken?

To prepare for such cases, the Java class loader is verified through a very strict and tight process. The JVM specifications explicitly detail the process.

Note

How can we verify that the JVM successfully executes the class file verification process? How can we verify that various JVMs from various JVM vendors satisfy the JVM specifications? For verification, Oracle provides a test tool, TCK (Technology Compatibility Kit). The TCK verifies a JVM specification by executing ten thousands of tests, including a many incorrect class files in various ways. After passing the TCK, the JVM can be called a JVM.

Like TCK, there is JCP (Java Community Process; http://jcp.org), which proposes new Java technical specifications as well as Java specifications. For the JCP, a specification document, reference implementation, and TCK for a proposed JSR (Java Specification Request) must be completed to complete JSR. Users who want to use new Java technology proposed as JSR should license the implementation from the RI provider, or directly implement it and test the implementation with TCK.

JVM Structure

The code written in Java is executed by following the process shown in the figure below.

Figure 1: Java Code Execution Process.

A class loader loads the compiled Java Bytecode to the Runtime Data Areas, and the execution engine executes the Java Bytecode.

Class Loader

Java provides a dynamic load feature; it loads and links the class when it refers to a class for the first time at runtime, not compile time. JVM's class loader executes the dynamic load. The features of Java class loader are as follows:

- Hierarchical Structure: Class loaders in Java are organized into a hierarchy with a parent-child relationship. The Bootstrap Class Loader is the parent of all class loaders.

- Delegation mode: Based on the hierarchical structure, load is delegated between class loaders. When a class is loaded, the parent class loader is checked to determine whether or not the class is in the parent class loader. If the upper class loader has the class, the class is used. If not, the class loader requested for loading loads the class.

- Visibility limit: A child class loader can find the class in the parent class loader; however, a parent class loader cannot find the class in the child class loader.

- Unload is not allowed: A class loader can load a class but cannot unload it. Instead of unloading, the current class loader can be deleted, and a new class loader can be created.

Each class loader has its namespace that stores the loaded classes. When a class loader loads a class, it searches the class based on FQCN (Fully Qualified Class Name) stored in the namespace to check whether or not the class has been already loaded. Even if the class has an identical FQCN but a different namespace, it is regarded as a different class. A different namespace means that the class has been loaded by another class loader.

The following figure illustrates the class loader delegation model.

Figure 2: Class Loader Delegation Model.

When a class loader is requested for class load, it checks whether or not the class exists in the class loader cache, the parent class loader, and itself, in the order listed. In short, it checks whether or not the class has been loaded in the class loader cache. If not, it checks the parent class loader. If the class is not found in the bootstrap class loader, the requested class loader searches for the class in the file system.

- Bootstrap class loader: This is created when running the JVM. It loads Java APIs, including object classes. Unlike other class loaders, it is implemented in native code instead of Java.

- Extension class loader: It loads the extension classes excluding the basic Java APIs. It also loads various security extension functions.

- System class loader: If the bootstrap class loader and the extension class loader load the JVM components, the system class loader loads the application classes. It loads the class in the $CLASSPATH specified by the user.

- User-defined class loader: This is a class loader that an application user directly creates on the code.

Frameworks such as Web application server (WAS) use it to make Web applications and enterprise applications run independently. In other words, this guarantees the independence of applications through class loader delegation model. Such a WAS class loader structure uses a hierarchical structure that is slightly different for each WAS vendor.

If a class loader finds an unloaded class, the class is loaded and linked by following the process illustrated below.

Figure 3: Class Load Stage.

Each stage is described as follows.

- Loading: A class is obtained from a file and loaded to the JVM memory.

- Verifying: Check whether or not the read class is configured as described in the Java Language Specification and JVM specifications. This is the most complicated test process of the class load processes, and takes the longest time. Most cases of the JVM TCK test cases are to test whether or not a verification error occurs by loading wrong classes.

- Preparing: Prepare a data structure that assigns the memory required by classes and indicates the fields, methods, and interfaces defined in the class.

- Resolving: Change all symbolic references in the constant pool of the class to direct references.

- Initializing: Initialize the class variables to proper values. Execute the static initializers and initialize the static fields to the configured values.

The JVM specification defines the tasks. However, it allows flexible application of the execution time.

Runtime Data Areas

Figure 4: Runtime Data Areas Configuration.

Runtime Data Areas are the memory areas assigned when the JVM program runs on the OS. The runtime data areas can be divided into 6 areas. Of the six, one PC Register, JVM Stack, and Native Method Stack are created for one thread. Heap, Method Area, and Runtime Constant Pool are shared by all threads.

- PC register: One PC (Program Counter) register exists for one thread, and is created when the thread starts. PC register has the address of a JVM instruction being executed now.

- JVM stack: One JVM stack exists for one thread, and is created when the thread starts. It is a stack that saves the struct (Stack Frame). The JVM just pushes or pops the stack frame to the JVM stack. If any exception occurs, each line of the stack trace shown as a method such as printStackTrace() expresses one stack frame.

Figure 5: JVM Stack Configuration.

−Stack frame: One stack frame is created whenever a method is executed in the JVM, and the stack frame is added to the JVM stack of the thread. When the method is ended, the stack frame is removed. Each stack frame has the reference for local variable array, Operand stack, and runtime constant pool of a class where the method being executed belongs. The size of local variable array and Operand stack is determined while compiling. Therefore, the size of stack frame is fixed according to the method.

−Local variable array: It has an index starting from 0. 0 is the reference of a class instance where the method belongs. From 1, the parameters sent to the method are saved. After the method parameters, the local variables of the method are saved.

−Operand stack: An actual workspace of a method. Each method exchanges data between the Operand stack and the local variable array, and pushes or pops other method invoke results. The necessary size of the Operand stack space can be determined during compiling. Therefore, the size of the Operand stack can also be determined during compiling.

- Native method stack: A stack for native code written in a language other than Java. In other words, it is a stack used to execute C/C++ codes invoked through JNI (Java Native Interface). According to the language, a C stack or C++ stack is created.

- Method area: The method area is shared by all threads, created when the JVM starts. It stores runtime constant pool, field and method information, static variable, and method bytecode for each of the classes and interfaces read by the JVM. The method area can be implemented in various formats by JVM vendor. Oracle Hotspot JVM calls it Permanent Area or Permanent Generation (PermGen). The garbage collection for the method area is optional for each JVM vendor.

- Runtime constant pool: An area that corresponds to the constant_pool table in the class file format. This area is included in the method area; however, it plays the most core role in JVM operation. Therefore, the JVM specification separately describes its importance. As well as the constant of each class and interface, it contains all references for methods and fields. In short, when a method or field is referred to, the JVM searches the actual address of the method or field on the memory by using the runtime constant pool.

- Heap: A space that stores instances or objects, and is a target of garbage collection. This space is most frequently mentioned when discussing issues such as JVM performance. JVM vendors can determine how to configure the heap or not to collect garbage.

Let's go back to the disassembled bytecode we discussed previously.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

|

public

void

add(java.lang.String);

Code:

0

: aload_0

1

: getfield #

15

;

//Field admin:Lcom/nhn/user/UserAdmin;

4

: aload_1

5

: invokevirtual #

23

;

//Method com/nhn/user/UserAdmin.addUser:(Ljava/lang/String;)Lcom/nhn/user/User;

8

: pop

9

:

return

|

Comparing the disassembled code and the assembly code of the x86 architecture that we sometimes see, the two have a similar format, OpCode; however, there is a difference in that Java Bytecode does not write register name, memory addressor, or offset on the Operand. As described before, the JVM uses stack. Therefore, it does not use register, unlike the x86 architecture that uses registers, and it uses index numbers such as 15 and 23 instead of memory addresses since it manages the memory by itself. The 15 and 23 are the indexes of the constant pool of the current class (here, UserService class). In short, the JVM creates a constant pool for each class, and the pool stores the reference of the actual target.

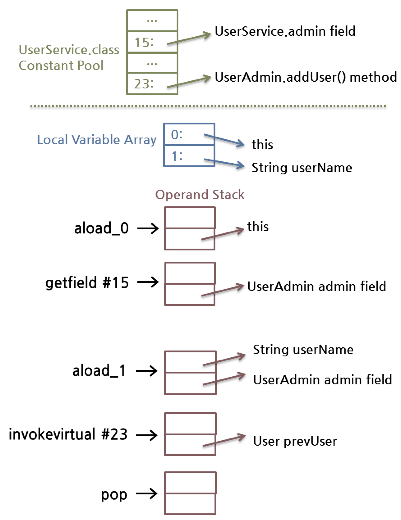

Each row of the disassembled code is interpreted as follows.

- aload_0: Add the #0 index of the local variable array to the Operand stack. The #0 index of the local variable array is always this, the reference for the current class instance.

- getfield #15: In the current class constant pool, add the #15 index to the Operand stack. UserAdmin admin field is added. Since the admin field is a class instance, a reference is added.

- aload_1: Add the #1 index of the local variable array to the Operand stack. From the #1 index of the local variable array, it is a method parameter. Therefore, the reference of String userName sent while invoking add() is added.

- invokevirtual #23: Invoke the method corresponding to the #23 index in the current class constant pool. At this time, the reference added by using getfield and the parameter added by using aload_1 are sent to the method to invoke. When the method invocation is completed, add the return value to the Operand stack.

- pop: Pop the return value of invoking by using invokevirtual from the Operand stack. You can see that the code compiled by the previous library has no return value. In short, the previous has no return value, so there was no need to pop the return value from the stack.

- return: Complete the method.

The following figure will help you understand the explanation.

Figure 6: Example of Java Bytecode Loaded on Runtime Data Areas.

For reference, in this method, no local variable array has been changed. So the figure above displays the changes in Operand stack only. However, in most cases, local variable array is also changed. Data transfer between the local variable array and the Operand stack is made by using a lot of load instructions (aload, iload) and store instructions (astore, istore).

In this figure, we have checked the brief description of the runtime constant pool and the JVM stack. When the JVM runs, each class instance will be assigned to the heap, and class information including User, UserAdmin, UserService, and String will be stored in the method area.

Execution Engine

The bytecode that is assigned to the runtime data areas in the JVM via class loader is executed by the execution engine. The execution engine reads the Java Bytecode in the unit of instruction. It is like a CPU executing the machine command one by one. Each command of the bytecode consists of a 1-byte OpCode and additional Operand. The execution engine gets one OpCode and execute task with the Operand, and then executes the next OpCode.

But the Java Bytecode is written in a language that a human can understand, rather than in the language that the machine directly executes. Therefore, the execution engine must change the bytecode to the language that can be executed by the machine in the JVM. The bytecode can be changed to the suitable language in one of two ways.

- Interpreter: Reads, interprets and executes the bytecode instructions one by one. As it interprets and executes instructions one by one, it can quickly interpret one bytecode, but slowly executes the interpreted result. This is the disadvantage of the interpret language. The 'language' called Bytecode basically runs like an interpreter.

- JIT (Just-In-Time) compiler: The JIT compiler has been introduced to compensate for the disadvantages of the interpreter. The execution engine runs as an interpreter first, and at the appropriate time, the JIT compiler compiles the entire bytecode to change it to native code. After that, the execution engine no longer interprets the method, but directly executes using native code. Execution in native code is much faster than interpreting instructions one by one. The compiled code can be executed quickly since the native code is stored in the cache.

However, it takes more time for JIT compiler to compile the code than for the interpreter to interpret the code one by one. Therefore, if the code is to be executed just once, it is better to interpret it instead of compiling. Therefore, the JVMs that use the JIT compiler internally check how frequently the method is executed and compile the method only when the frequency is higher than a certain level.

Figure 7: Java Compiler and JIT Compiler.

How the execution engine runs is not defined in the JVM specifications. Therefore, JVM vendors improve their execution engines using various techniques, and introduce various types of JIT compilers.

Most JIT compilers run as shown in the figure below:

Figure 8: JIT Compiler.

The JIT compiler converts the bytecode to an intermediate-level expression, IR (Intermediate Representation), to execute optimization, and then converts the expression to native code.

Oracle Hotspot VM uses a JIT compiler called Hotspot Compiler. It is called Hotspot because Hotspot Compiler searches the 'Hotspot' that requires compiling with the highest priority through profiling, and then it compiles the hotspot to native code. If the method that has the bytecode compiled is no longer frequently invoked, in other words, if the method is not the hotspot any more, the Hotspot VM removes the native code from the cache and runs in interpreter mode. The Hotspot VM is divided into the Server VM and the Client VM, and the two VMs use different JIT compilers.

Figure 9: Hotspot Client VM and Server VM.

The client VM and the server VM use an identical runtime; however, they use different JIT compilers, as shown in the above figure. The client VM and the server VM use an identical runtime, however, they use different JIT compilers as shown in the above figure. Advanced Dynamic Optimizing Compiler used by the server VM uses more complex and diverse performance optimization techniques.

IBM JVM has introduced AOT (Ahead-Of-Time) Compiler from IBM JDK 6 as well as the JIT compiler. This means that many JVMs share the native code compiled through the shared cache. In short, the code that has been already compiled through the AOT compiler can be used by another JVM without compiling. In addition, IBM JVM provides a fast way of execution by pre-compiling code to JXE (Java EXecutable) file format using the AOT compiler.

Most Java performance improvement is accomplished by improving the execution engine. As well as the JIT compiler, various optimization techniques are being introduced so the JVM performance can be continuously improved. The biggest difference between the initial JVM and the latest JVM is the execution engine.

Hotspot compiler has been introduced to Oracle Hotspot VM from version 1.3, and JIT compiler has been introduced to Dalvik VM from Android 2.2.

Note

The technique in which an intermediate language such as bytecode is introduced, the VM executes the bytecode, and the JIT compiler improves the performance of JVM is also commonly used in other languages that have introduced intermediate languages. For Microsoft's .Net, CLR (Common Language Runtime), a kind of VM, executes a kind of bytecode, called CIL (Common Intermediate Language). CLR provides the AOT compiler as well as the JIT compiler. Therefore, if source code is written in C# or VB.NET and compiled, the compiler creates CIL and the CIL is executed on the CLR with the JIT compiler. The CLR uses the garbage collection and runs as a stack machine like the JVM.

The Java Virtual Machine Specification, Java SE 7 Edition

On 28th July, 2011, Oracle released Java SE 7 and updated the JVM specifications to Java SE 7 version. After releasing "The Java Virtual Machine Specification, Second Edition" in 1999, it took 12 years for Oracle to release the updated version. The updated version includes various changes and modifications accumulated over 12 years, and describes more clear specifications. In addition, it reflects the contents included in "The Java Language Specification, Java SE 7 Edition" released with Java SE 7. The major changes can be summarized as follows:

- Generics introduced from Java SE 5.0, supporting variable argument method

- Bytecode verification process technique changed since Java SE 6

- Added invokedynamic instruction and related class file formats for supporting dynamic type languages

- Deleted the description of the concept of the Java language itself and referred reader to the Java language specifications

- Deleted the description on Java Thread and Lock, and transferred these to the Java language specifications

The biggest change of these is the addition of invokedynamic instruction. This means that a change was made in the JVM internal instruction sets, as the JVM started to support dynamic type languages of which type is not fixed, such as script languages, as well as Java language from Java SE 7. The OpCode 186 which had not been used previously has been assigned to the new instruction, invokedynamic, and new contents have been added to the class file format to support the invokedynamic.

The version of the class file created by the Java compiler of Java SE 7 is 51.0. The version of Java SE 6 is 50.0. Much of the class file format has been changed. Therefore, class files with version 51.0 cannot be executed in the Java SE 6 JVM.

Despite these various changes, the 65535 byte limit of the Java method has not been removed. Unless the JVM class file format is innovatively changed, it may not be removed in the future.

For reference, Oracle Java SE 7 VM supports G1, the new garbage collection; however, it is limited to the Oracle JVM, so JVM itself does not limit any garbage collection type. Therefore, the JVM specifications do not describe that.

String in switch Statements

Java SE 7 adds various grammars and features. However, compared to the various changes in language of Java SE 7, there are not so many changes in the JVM. So, how can the new features of the Java SE 7 be implemented? We will see how String in switch Statements (a function to add a string to a switch() statement as a comparison) has been implemented in Java SE 7 by disassembling it.

For example, the following code has been written.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

|

// SwitchTest

public

class

SwitchTest {

public

int

doSwitch(String str) {

switch

(str) {

case

"abc"

:

return

1

;

case

"123"

:

return

2

;

default

:

return

0

;

}

}

}

|

Since it is a new function of Java SE 7, it cannot be compiled using the Java compiler for Java SE 6 or lower versions. Compile it using the javac of Java SE 7. The following screen is the compiling result printed by using javap –c.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

|

C:Test>javap -c SwitchTest.classCompiled from

"SwitchTest.java"

public

class

SwitchTest {

public

SwitchTest();

Code:

0

: aload_0

1

: invokespecial #

1

// Method java/lang/Object."<init>":()V

4

:

return

public

int

doSwitch(java.lang.String);

Code:

0

: aload_1

1

: astore_2

2

: iconst_m1

3

: istore_3

4

: aload_2

5

: invokevirtual #

2

// Method java/lang/String.hashCode:()I

8

: lookupswitch {

// 2

48690

:

50

96354

:

36

default

:

61

}

36

: aload_2

37

: ldc #

3

// String abc

39

: invokevirtual #

4

// Method java/lang/String.equals:(Ljava/lang/Object;)Z

42

: ifeq

61

45

: iconst_0

46

: istore_3

47

:

goto

61

50

: aload_2

51

: ldc #

5

// String 123

53

: invokevirtual #

4

// Method java/lang/String.equals:(Ljava/lang/Object;)Z

56

: ifeq

61

59

: iconst_1

60

: istore_3

61

: iload_3

62

: lookupswitch {

// 2

0

:

88

1

:

90

default

:

92

}

88

: iconst_1

89

: ireturn

90

: iconst_2

91

: ireturn

92

: iconst_0

93

: ireturn

|

A significantly longer bytecode than the Java source code has been created. First, you can see that lookupswitch instruction has been used for switch() statement in Java bytecode. However, two lookupswitch instructions have been used, not the one lookupswitch instruction. When disassembling the case in which int has been added to switch() statement, only one lookupswitch instruction has been used. This means that the switch() statement has been divided into two statements to process the string. See the annotation of the #5, #39, and #53 byte instructions to see how the switch() statement has processed the string.

In the #5 and #8 byte, first, hashCode() method has been executed and switch(int) has been executed by using the result of executing hashCode() method. In the braces of the lookupswitch instruction, branch is made to the different location according to the hashCode result value. String "abc" is hashCode result value 96354, and is moved to #36 byte. String "123" is hashCode result value 48690, and is moved to #50 byte.

In the #36, #37, #39, and #42 bytes, you can see that the value of the str variable received as an argument is compared using the String "abc" and the equals() method. If the results are identical, '0' is inserted to the #3 index of the local variable array, and the string is moved to the #61 byte.

In this way, in the #50, #51, #53, and #56 bytes, you can see that the value of the str variable received as an argument is compared by using the String "123" and the equals() method. If the results are identical, '1' is inserted to the #3 index of the local variable array and the string is moved to the #61 byte.

In the #61 and #62 bytes, the value of the #3 index of the local variable array, i.e., '0', '1', or any other value, is lookupswitched and branched.

In other words, in Java code, the value of the str variable received as the switch() argument is compared using the hashCode() method and the equals() method. With the result int value, switch() is executed.

In this result, the compiled bytecode is not different from the previous JVM specifications. The new feature of Java SE 7, String in switch is processed by the Java compiler, not by the JVM itself. In this way, other new features of Java SE 7 will also be processed by the Java compiler.

Conclusion

I don't think that we need to review how Java has been developed to use Java well. So many Java developers develop great applications and libraries without understanding JVM deeply. However, if you understand JVM, you will understand Java more, and it will be helpful to solve the problems like the case we have reviewed here.

Besides the description mentioned here, the JVM has various features and technologies. The JVM specifications provide a flexible specification for JVM vendors to provide more advanced performance so that various technologies can be applied by the vendor. In particular, garbage collection is the technique used by most languages that provides usability similar to that of a VM, the latest and state-of-the-art technique in its performance. However, as this has been discussed in many more prominent studies, I did not explain it deeply in this article.

For Korean speakers, if you need more information on the internal structure of JVM, I recommend you to refer to "Java Performance Fundamental" (Hando Kim, Seoul, EXEM, 2009). The book is written in Korean so it is easy to read. I have referenced this book as well as the JVM specifications to write this article. For English speaking readers, there should be many books covering Java Performance topic.

By Se Hoon Park, Messaging Platform Development Team, NHN Corporation.