#4# Jan 27th 2018

关键词:Social media and misinformation

WhatsApp: Mark Zuckerberg’s other headache

WhatsApp:马克扎克伯格的另一头疼事儿

The popular messaging service shows that Facebook’s efforts to fight fake news may fail

受欢迎的留言服务表明脸书努力打击虚假新闻可能会失败

“THERE’S too much sensationalism, misinformation and polarisation in the world today,” lamented(悲叹) Mark Zuckerberg, the boss of Facebook, recently. To improve things, the world’s largest social network will cut the amount of news in users’ feeds by a fifth and attempt to make the remainder more reliable by prioritising information from sources which users think are trustworthy.

“当今世界有太多哗众取宠、错误信息和两极分化。”脸书老总马克扎克伯格近来悲叹不已。为了改善事务,世界最大社交网络将推送给用户的新闻数量减少了1/5,通过优先选择用户所信赖的来源中的信息使剩下的新闻更可信赖。

Many publishers are complaining: they worry that their content will show up less in users’ newsfeeds, reducing clicks and advertising revenues. But the bigger problem with Facebook’s latest moves may be that they are unlikely to achieve much—at least if the flourishing of fake news on WhatsApp, the messaging app which Facebook bought in 2014 for $19bn, is any guide.

许多出版商抱怨:他们担心新闻内容会在用户新闻推送、降低点击数量和广告收入上减少一些。但脸书最近改变中更大的问题可能在于他们很有可能收效甚微——至少如果WhatsApp上虚假新闻遍地开花,脸书于2014年以190亿美元购买的该信息服务类软件就成了任意的向导。

In more ways than one, WhatsApp is the opposite of Facebook. Whereas posts on Facebook can be seen by all of a user’s friends, WhatsApp’s messages are encrypted. Whereas Facebook’s newsfeeds are curated by algorithms(算法) that try to maximise the time users spend on the service, WhatsApp’s stream of messages is solely generated by users. And whereas Facebook requires a fast connection, WhatsApp is not very data-hungry.

WhatsApp在不止一个方面和脸书大相径庭。发布在脸书上的信息可以被用户所有朋友看到,而WhatsApp上的信息却是加密的。脸书上会用算法统计新闻推送从而使用户花在该服务上的时间最大化,而WhatsApp上的信息流则仅仅由用户产生。脸书需要快速连接,而WhatsApp对数据的需求却没有那么饥渴。

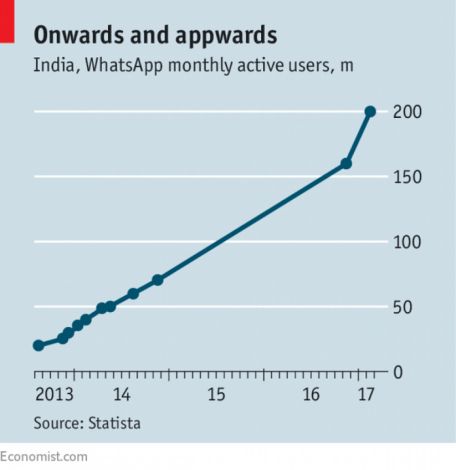

As a result, WhatsApp has become a social network to rival Facebook in many places, particularly in poorer countries. Of the service’s more than 1.3bn monthly users, 120m live in Brazil and 200m in India (see chart). With the exceptions of America, China, Japan and South Korea, WhatsApp is among the top three most-used social apps in all big countries.

结果,WhatsApp在许多地方尤其是更贫穷的国家成为了对手脸书的社交网络。在该服务超13亿的月度用户中,有1.2亿住在巴西,2亿在印度(见图表)。除了美国、中国、日本和韩国,WhatsApp在所有大国最常用的社交软件中已经排名前三。

Most of the 55bn messages sent every day are harmless, but WhatsApp’s scale attracts all sorts of mischief-makers. In South Africa the service is often used to spread false allegations of civic corruption and hoax warnings of storms, fires and other natural disasters. In Brazil rumours about people travel quickly: a mob recently set upon a couple they suspected of being child traffickers based on chatter on WhatsApp (the couple escaped).

每天发送的550亿信息中大多都是无害的,但是WhatsApp的规模却吸引了各种挑拨离间之人。在南非,该服务经常被用来散播对国内腐败的虚假指控和对暴风雨、火灾和其他自然灾害的警告骗局。在巴西,关于人民的谣言传播很快:近期一群暴徒袭击了一对他们根据WhatsApp上聊天记录认定是拐卖儿童贩子的情侣(这对情侣后来逃走了)。

But it is in India where WhatsApp has had the most profound effect. It is now part of the country’s culture: many older people use it and drive younger ones crazy by forwarding(转寄) messages indiscriminately(不加选择)—sometimes with tragic results. Last year, seven men in the eastern state of Jharkhand were murdered by angry villagers in two separate incidents after rumours circulated on WhatsApp warning of kidnappers in the area. In a gruesome(可怕的,阴森的) coda(结尾部分) to the incident, pictures and videos from the lynching also went viral.

但是受到WhatsApp影响最深远的国家却是印度。现在它已成为该国文化的一部分了:很多年纪稍长之人不加选择就转发信息,使得年轻人被搞得很抓狂,有时甚至带来悲剧。去年在东部的贾坎德邦,WhatsApp上面流传多则对绑架者进行警示的谣言之后,7个男人在两件独立事件中被暴怒的村民杀害。该事件可怖的结局就是该私刑的照片和视频被疯狂传播。

It is unclear how exactly such misinformation spreads, not least because traffic is encrypted. “It’s not that we have chosen not to look at it. It is impossible,” says Filippo Menczer of Indiana University’s Observatory(观察站) on Social Media, which tracks the spread of fake news on Twitter and other online services. Misinformation on WhatsApp is identified only when it jumps onto another social-media platform or, as in India, leads to tragic consequences.

这样的错误信息具体是如何散播的不得而知,最不可能的原因就是通道加密。“并非我们选择不看它,这是不可能的。”印第安纳大学社交媒体观察站的菲利波门采尔说。该观察站追踪推特和其他网络服务上虚假新闻的传播。WhatsApp上的错误信息只有跳到另一家社交平台或比如在印度导致悲剧时才被识别出来。

Some patterns are becoming clear, however. Misinformation often spreads via group chats, which people join voluntarily and whose members—family, colleagues, friends, neighbours—they trust. That makes rumours more believable. Misinformation does not always come in the form of links, but often as forwarded texts and videos, which look the same as personal messages, lending them a further veneer(外表,虚饰) of legitimacy(合法,合理). And since users often receive the same message in multiple groups, constant repetition makes them more believable yet.

然而,一些模式正愈发清晰可见。错误信息经常通过人们或者他们所信赖的家人、同事、朋友、邻居自愿加入的群聊散播出来。这就使得谣言更容易被相信。错误信息并非总是以链接的形式出现,但是经常作为看上去类似个人信息然后被转发出去的文本和视频出现,这样就给错误信息增添了一层合法外衣。由于用户经常在多个群中收到相同信息,不断的重复使得错误信息更容易被相信。

Predictably, propagandists have employed WhatsApp as a potent(有效的,强有力的) tool. In “Dreamers”, a book about young Indians, Snigdha Poonam, a journalist, describes visiting a political party’s “social media war room” in 2014. Workers spent their days “packaging as many insults as possible into one WhatsApp message”, which would then be sent out to party members to be propagated within their own networks. Similar tactics are increasingly visible elsewhere. Last month’s conference in South Africa of the African National Congress, at which delegates elected a new party leader, saw a flood of messages claiming victory for and conspiracy(阴谋) by both factions(派别). With elections due in Brazil and Mexico this year, and in India next year, expect more such shenanigans(诡计,恶作剧).

可以预测到,传播者运用了WhatsApp作为有力工具。《追梦人》一书描绘了年轻的印第安人、Snigdha Poonam和一名记者在2014年参观一政党的“社交战斗屋”的经历。工作人员整天把尽可能多的辱骂之言打包汇总成一则WhatsApp消息,然后发送给党内成员进行内网传播。我们在其他地方也逐渐可以见到相似的策略。在上个月非洲国会的南非会议中,代表们选出了一位新的党内领导人,两派声称胜利和阴谋的消息多如洪水。今年的巴西和墨西哥选举,明年的印度选举,都将会有更多这样的恶作剧出现。

Governments and WhatsApp itself are keenly(敏锐地,强烈地) aware of the problem. In India authorities now regularly block WhatsApp to stop the spread of rumours, for instance of salt shortages. Regulators in Kenya, Malaysia and South Africa have mooted(提出…供讨论) the idea of holding moderators (主持人,版主)of group chats liable for false information in their groups. WhatsApp is working on changing the appearance of forwarded messages in the hope that visual cues(提示,暗示) will help users tell the difference between messages from friends and those of unknown provenance(出处,起源). But ultimately it will be down to users to be more responsible and not blindly forward messages they receive.

政府和WhatsApp自身也强烈意识到这个问题。现在印度官方定期封锁WhatsApp阻止谣言传播,比如食盐短缺的谣言。肯尼亚、马来西亚和南非的调控人员已经提出拘留群内易出现虚假信息群主的想法。WhatsApp正致力于改变被转发消息的外观,以期通过视觉提示来帮助用户区分朋友发送的信息和来源不明的信息。但是最终还是要依赖用户更具责任感,不盲目转发他们接收到的信息。

It is as yet unclear whether fake news on Facebook will be less of a problem after it changes its algorithms. The experience of WhatsApp suggests, however, that the concerns will persist. “Even with all these countermeasures, the battle will never end,” Samidh Chakrabarti, a Facebook executive admitted on January 22nd. “Misinformation campaigns are not amateur operations. They are professionalised and constantly try to game the system.”

脸书改变算法后上面的虚假新闻是否会减少目前还不清楚。但是,WhatsApp的经历表明人们对其的关注还会继续。“甚至采取所有对抗措施,战争也绝不会结束。”脸书执行官Samidh Chakrabarti于1月22日坦言。“与错误信息的争斗并非业余行动。它们是专业化的,并持续尝试运用系统规则。”