我們學會思考的那一天——紀錄片文字記錄

The Day We Learned To Think - programme transcript

旁白(約翰·夏普尼爾):

NARRATOR (JOHN SHRAPNEL)

這是他們當中最偉大的一個。當我們從類人猿進化到現代人類時,我們是否獲得了交談的能力,給予我們周圍的世界以意義,去思考?我們什麼時候真正停止了動物性質的生活,進化成真正的人類呢?現在我們可能從一小塊石頭中尋求答案。這小片赭石最終能解開一個10萬年前的謎團,這是我們學會思考那一天的奧秘。在印度洋與大西洋相連的南非的野生海岸上,隱藏一個洞穴。今天它被遺棄了,但它曾經充滿了活力。就在這裏,幾萬年前,我們一些最早的祖先曾經生活在這裏。

南非海岸的洞穴

Caves on the coast of South Africa

克裏斯·亨施伍德教授(非洲遺產研究所):

PROF CHRIS HENSHILWOOD (African Heritage Research Institute)

我喜歡把這個海岸沿線的地區想象成伊甸的原始花園。你真的擁有了你所需要的一切。

旁白:

在過去的10年裏,這個洞穴一直是人類學家克裏斯·亨施伍德的人生。每年他都在這裏不斷地挖掘,越來越深入地尋找關於生活在這裏人類的線索,有一天他偶然發現了一些他從來未期望看到的東西,根據查閱所有的教科書,這些東西根本就不應該存在於這裏。

克裏斯·亨施伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

這絕對令人難以置信的圖像出現了,你能想象的到這足以使人產生巨大的興奮和激動。每個人都在這個地方跳來跳去。這是一個沒有人會產生爭議而又明確的圖像,是故意創造出来的。

旁白:

亨施伍德的發現有可能徹底改變我們對人類最大難題之一的理解。曆史書籍毫無疑問需要重新編寫,並且長期的理論也很可能被撕毀。因為他發現了其中之一偉大的科學偵探故事可能最終被解決:我們的祖先什麼時候不再是野蠻動物,何時首先成為真正的人類?我們什麼時候學會思考?思維是人類的決定性特征。它給了我們今天的機器、技術和力量。沒有其他動物有能力看到外面的世界並改變它。思考使我們成為了我們—— 這是有史以來最具優勢的物種。在所有其他動物日複一日生活的情況下,我們獨自計劃著前進,夢想和創造。

南非海岸的洞穴挖掘出的赭石

The South African coast caves excavated ochre

理查德·克萊恩(斯坦福大學古人類學家):

PROF RICHARD KLEIN (Stanford University)

那麼我想,如果我不得不孤立一種我認為會標志現代人類的特質,那麼就是它的創新性,創造性,以及隨時引入和發明新事物的能力。沒有其他動物物種在不斷地重塑和改變自己的行為。

旁白:

理查德·克萊恩教授認為,藝術是人類進化的裏程碑。毫無疑問,這是一種廣泛而普遍的藝術,表明你正在和我們這樣的人打交道。畢竟,沒有其他動物能夠把一幅畫定義為一種顏色和形狀的集合。這種能力是人類獨有的。但是這種創造性和主宰我們周圍世界的關鍵能力究竟發生在何時?找到我們學會思考的那一天,你會發現人類曆史上唯一最重要的時刻。

其他科學家也同意。他們認為藝術將人類定義為行為上的現代,它的開始必須與說話和使用語言的能力相一致。如果有人能想象出一種用藝術來描述他們的環境的共享方式,那麼他們就無法擁有語言和語言,這似乎是不可想象的。我們的祖先在行為上的探索和我們一樣,也是對第一個藝術證據的追尋。

艾利森·布魯克斯(喬治華盛頓大學):

PROF ALISON BROOKS (George Washington University)

我們基本上生活在我們頭腦中所創造的世界中。如果你環顧四周,你所生活的一切都是由人類創造的。這是一個令人著迷的發展。我們如何表現我們的行為方式?這是什麼時候發生的?

旁白:

尋找這個問題的答案已經成為科學最偉大的任務之一,但它不會是簡單的。思維不會留下任何痕跡。沒有任何僵化的思想等待著被挖掘出來並注明地點和日期。這就像調查一個沒有屍體的謀殺現場。因此科學家們不得不尋找間接的線索——而不是化石,但其他證據表明,當思維開始時,他們意識到,思維一定是與其他東西聯系在一起的。

蒙太奇的男士:

來吧,這有四磅一磅的香蕉......女士:哦,是的,我昨天試著和她說話。女士:是的,你不是......女士:不,我不知道......

思維也意味著說話。

男士:

給我一些......

旁白:

為了我們能夠改變世界,我們的思想需要交流。

女士:

非常感謝,謝謝。

旁白:

所以科學家得出結論,只有當我們具備了語言能力時,思維才會產生。

蒙太奇男士:

......完全空洞。男士:......做一個簡單的錯誤。男士:......有一天他發現了手機...... 喬治·布什:讀我的唇語。

蘭德爾·懷特教授(紐約大學考古學家):

PROF RANDALL WHITE (Archaeologist at New York university)

語言,這的確是一個至關重要的界限。擁有事物的能力,可以代表其他事物,在一種文化中,甚至在一個物種中代表某事物或者代表某種東西,或其他事物。

旁白:

但另一方面是考古學家們又一次遇到了同樣的問題。沒有古老的錄音磁帶,而寫作只是最近才發明的。

艾莉森·布魯克斯(ALISON BROOKS):

我們要找什麼?首先,它將給我們證據,證明人類的行為是現代的。

男士:

......她所受到的高度尊重。

艾莉森·布魯克斯(ALISON BROOKS):

我們對於如何獲得這些東西的證據感到困惑,所以我們尋找代理的方法。但是有一種考古學家可以找到的證據,是一種思想的證明和一種你希望看到的語言形式。

旁白:

但是考古學家們可以找到一種證據,一種可以證明思想的東西,和你希望看到的一種清晰的語言形式。

理查德·克萊恩(RICHARD KLEIN):

我們如何在考古記錄中發現創造力?一個明顯的證據就是藝術。當你得到了廣泛而普遍的無可置疑的藝術時,我認為你可以說你是在和像我們這樣的人打交道。

旁白:

只有人類能夠創造,並能理解藝術。

特倫斯·迪肯教授(加州大學伯克利分校):

PROF TERRENCE DEACON (University of California, Berkeley)

我相信在過去的幾年裏,有幾十只狗沿著這條路走下去,也許沒有人抬頭看一眼它,這是什麼意思呢?對狗來說,這是牆上的顏色,也許比那還要少。

旁白:

但是對一個人來說,繪畫遠不止是一堆顏色。它是一種語言,一種思想的表達。

特倫斯·迪肯(TERRENCE DEACON):

在很多方面,這變成了一種說話方式。這是一個故事。事實上,很多很多故事。聽者,讀者,旁觀者已解碼的故事,所以當你看到這幅壁畫,看到所有這些不同的圖像時,你不會看到這些圖片,你不看看這些圖片,你不看看這些顏色,你不看看這些對他們所做的,你看看他們的意思。

現代壁畫

Modern frescoes

旁白:

對於考古學家來說,藝術、語言和思想都是同一件事,這是一個巨大的突破。突然間他們要尋找的東西是很清楚的。因為發現最早的人類藝術形式,那麼你就會發現我們學會思考的那一天。幾十年前,考古學家開始尋找古老藝術的存在。他們觀察了一個顯而易見的地方:非洲,人類進化的搖籃,但他們在那裏什麼也沒找到。他們追溯了早期人類通過中東從非洲走出來的道路。在那裏也是什麼都沒有找到。因此考古學家轉向了歐洲,發現了一個前所未有的奇跡——第一個洞穴岩畫,驚人的制作和細節精美。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

這是他們對周圍世界的描述,所以當我走進其中一個洞穴時,我絕對會覺得,在很小的比例下,我能夠看到他們所看到世界的樣子。我們可以像這樣走進一個洞穴,說我理解,我理解這個謎。一個那時的現代人會這樣做,我也會這麼做。

旁白:

他們還發現了更多:精致的小雕像;數以千計的珠寶首飾。最後在歐洲,考古學家們一直在尋找一種具有象征意義的藝術,這種藝術只能由那些能夠說話和思考的人創造出來,就像我們一樣,而且都是在大約35000年前的同一時期。歐洲的證據是毋庸置疑的。這就像一個燈泡在人腦裏面,一個大爆炸的想法。出於某種原因,我們突然變成了真正的現代人。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

人類頭腦中的所有元素都在創造一切,創造出後來存在的一切——去月球,創造寫作,創造農業,完成我們在隨後的35000年裏所做的所有事情。

旁白:

看來,當我們學會思考的那一刻似乎已經找到了。人類曆史上這個具有裏程碑意義的時刻被稱為人類革命。這場人類革命的威力究竟有多大呢?已經被其他事情所證明,但這更是令人不安的事。因為當我們的祖先第一次到達歐洲的時候,35000到40000年前,已經有人在等待他們了,這是另一種人類,他們在歐洲生活了幾十萬年,他們被稱為尼安德特人。

讓-雅克·於布蘭教授(波爾多大學):

(PROF JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN,University of Bordeaux)

我們很難去接受甚至理解同一個世界上不同種類的人類的這種觀念。非常,非常的奇怪。

旁白:

尼安德特人與我們一樣,是人類大家庭的一部分,更接近於像黑猩猩一樣的動物,但因為他們早在我們的祖先之前就已經從非洲走出來了,他們的進化過程非常不同。

讓-雅克·於布蘭(JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN):

尼安德特人的臉部較長,他們臉的中部也很突出。尼安德特人可能有很大很突出的鼻子,這可能是一個非常突出的特征。

旁白:

在歐洲,尼安德特人的家園被一系列的冰河時代所破壞。這是一種非常艱難的環境,在這種環境下塑造了他們的整個外貌。

讓-雅克·於布蘭(JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN):

它們有長長的軀幹和相當短的四肢,這是能讓它們身體保持溫暖的體型。我想說它們看起來有點像愛斯基摩人。他們非常適應這個充滿挑戰和變化的環境,但在大約4萬年前,發生了一些以前從未發生過的事情。

旁白:

發生的事情是現代人類的到來。經過25萬年的生活,尼安德特人幾乎在一夜之間滅絕了。對於科學家來說,現代人的到來和尼安德特人的消失不僅僅是一種巧合。當他們研究尼安德特人的工具時,第一個了解到可能發生事件的線索。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

當你看到尼安德特人的某些方面,尼安德特人的考古記錄會讓你撓頭,因為你說我不明白,我不會那樣做,他們為什麼不這樣做呢?

旁白:

尼安德特人所使用的工具,在一些至關重要的方面與我們的截然不同:一切都簡單得多,最重要的是與那時的現代人類不同,尼安德特人沒有體現出藝術的作品,所以沒有證據證明這些原始人類可以思考。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

由這樣一群人就能夠很好的溝通,以便有能力更好地發明,面對那些在30萬年的傳統生活中沒有聚集起來的人群,可以使他們能夠更好地組織起來。在我看來,競爭不會持續很長時間。

旁白:

既然無法像我們這樣思考,顯然較差的尼安德特人被推到了滅絕的邊緣,直到最後他們完全消失了。這就是人類革命力量的最後證明。那些突如其來的思想使我們能夠超越我們最親近的親戚。人類革命給了我們征服這個世界的力量。但隨後的抱怨就開始了。一個奇怪的反常現象出現了,它與人類革命的故事不太相符。當科學家們開始尋找另一種被認為是思維的證據,不是藝術,而是語言的時候它就開始了。是生物人類學家傑弗裏·萊特曼(Jeffrey Laitman)引起的混亂,他是解剖學專家,特別是人體的一小部分的解剖,我們用來說話的部分:喉嚨。

傑弗雷·萊特曼教授(西奈山醫學院):

PROF JEFFREY LAITMAN (Mount Sinai School of Medicine)

喉部可以說是所有人體解剖學和生理學中最重要的區域。作為一名土生土長的紐約人,我喜歡把它想象成人類身體的中央車站。(背景聲音)這些都是很好的,這是一個非常清晰的畫面...

旁白:

萊特曼開始研究人聲盒,或喉部。他發現,在進化過程中,我們的喉頭已經轉移到了與其他所有哺乳動物截然不同的位置。

傑弗雷·萊特曼(JEFFREY LAITMAN):

在你和我身上發生了一些事情,而發生的事情卻相當驚人。我們的喉已經下降到喉嚨裏了。當然,一個關鍵的好處是,喉嚨裏的喉頭比喉部低,所以我們得到的是能夠使我們轉變的一種機制,它使我們的聲音變得明亮起來,成為小號的號角。(背景聲音)圍繞......我跟隨哪一個(一起談話)這裏漂亮,漂亮...

旁白:

下喉給我們的是說話的能力。(背景聲音)...上唇在這裏。對,你可以在...

旁白:

所以,萊特曼開始思考:什麼時候這種下降的喉嚨實際上可以發聲的,又是什麼時候我們獲得了這種說話能力?他的研究顯示,在數百萬年的進化過程中,我們頭骨的形狀發生了變化,導致喉頭下降。

傑弗雷·萊特曼(JEFFREY LAITMAN):

最大的區別是當你找到了成年人類的時候。當你看他們的頭骨底部時,你會看到一個小山穀,一條溝壑,這是非常不同的,我們發現的關系是底部非常彎曲的頭骨,就像這樣,它與喉嚨不高的位置有關,而喉頭的位置則更低。

旁白:

帶有溝壑形狀的頭骨與說話的能力是密不可分的,所以萊特曼開始著手調查。語言這一關鍵發展是什麼時候發生的呢?從更遠的地方觀察頭骨,他發現了一些令人費解的東西。

傑弗雷·萊特曼(JEFFREY LAITMAN):

在我們的物種早期,智人,大約10萬到20萬年之前,我們開始看到和活著的人類擁有幾乎相同的特征。

旁白:

現代的溝壑形狀和說話能力至少在20萬年前就已經達到了,早在人類革命之前。

傑弗雷·萊特曼(JEFFREY LAITMAN):

所以他們解剖了它。他們是否像我們一樣說話?現在我們進入虛擬世界。我不在那裏。然而,如果你有一輛漂亮的汽車,大發動機和所有輪胎,你認為汽車將要運行,並且運行速度會非常快,否則為什麼它有那麼大的發動機,為什麼它有這些漂亮的輪胎?這就是我們正在處理的問題。

旁白:

然後在以色列發生了一些事情,甚至進一步加劇了情節。1989年,在一個考古遺址第一次挖掘出一塊尼安德特人的骨骼,被稱為舌骨。

瑪格麗特·克萊格博士(倫敦大學學院 ):

DR MARGARET CLEGG (University College London)

舌骨是你的聲道一根骨頭,它就在這裏,如果你用手指按壓,你實際上可以感受到骨頭的形狀。

旁白:

就像現代人類一樣,尼安德特人的舌骨在形成喉部的過程中起著至關重要的作用。科學家們第一次可以將我們的聲音與尼安德特人的聲音進行比較,結果他們大吃一驚。舌骨實際上是相同的。

瑪格麗特·克萊格博士(Dr MARGARET CLEGG):

在尼安德特人和現代人類中,舌骨和顱底以及面部和顱骨之間的關系是相同的,並且其含義是舌骨將與其現代人類在相同位置。它的喉嚨很低。

旁白:

換句話說,就像現代人,尼安德特人的喉部很低。這意味著他們的身體上已經具有了語言能力。事實上,在某些方面,他們甚至可能做得更好。

瑪格麗特·克萊格博士(Dr MARGARET CLEGG):

尼安德特人的特點是雖然他們的聲道與我們的相似,但在尼安德特人身上卻有著差異。他們有巨大的胸部,有巨大的鼻子和巨大的鼻竇。現在大的胸部和大鼻子會使他們產生更大的聲音,也許和一個普通的人比起來,他們更像一個歌劇演唱家。

旁白:

現在有一個明顯的矛盾。根據人類革命理論學說,我們四萬年前才學會思考,這就是歐洲突然出現的藝術證據,但是根據化石提供的證據,表明其他的思維和說話能力早在16萬年前就出現了,只是沒有意義了。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

這給我們的考古學家提出了一個嚴肅的問題,它提出了一個嚴肅的問題,因為它說,好的,你可以在10萬年前在非洲擁有解剖學上的現代人類,但為什麼他們只是解剖學意義上的現代人類,而不是他們能夠做出一切好東西,就像我們在歐洲所看到的最早的現代人類,為什麼看不到洞穴裏的岩石畫,為什麼沒有這些雕刻的實際物體?

旁白:

對於像理查德·克萊恩這樣的人類革命理論的支持者來說,現在遇到了一個真正的困難。如何調和藝術與解剖學之間出現的矛盾以及相關證據,克萊恩提出了一個激進的理論。即使人類早期有語言的解剖結構,但他們也沒有能力使用它。然而,與其他進化過程相比,變化在逐漸發生,人類的思維突然間被一個單一的、反常的基因突變所改變和打開。只有到那時,我們才開始思考、說話和創造藝術。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

我認為,發生在四萬年前或五萬年前的事情是,基因突變使人們比以前更具創造性,思考方式不同,並能夠提出問題,如果以這種方式制作的工具是什麼,結果會是怎樣,以前從來沒有人能夠做到。

旁白:

據克萊恩分析認為,思維並不是通過逐漸進化而出現的,但很可能是突然性或戲劇性產生的飛躍。這就好像我們被上帝遺傳了一樣。對克萊恩來說,這種突然的覺醒是如此的強大,這是我們為什麼要取代尼安德特人的唯一可能的解釋。我們具備了思維基因,但他們沒有。

蘭德爾·懷特(RANDALL WHITE):

我的觀點是肯定的,如果你喜歡肯定有基因的丟失,讓他們無法表現完全現代人類的方式,幫助我們理解為什麼當現代人類或許在四萬或四萬五千年前出現在歐洲之時,他們能夠完全取代了當地的尼安德特人。

旁白:

這是一個大膽的假設,也是一個令人信服的假設。人類革命理論仍然是我們學會思考的最好的解釋。但是,在2000年,在世界的另一端,從歐洲到非洲,出現了一些完全出乎意料的事情。在南非東海岸的布隆博斯(Blombos),人類學家克裏斯·亨希爾伍德在他的史前洞穴裏悄悄地挖掘了十多年。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

這是布隆博斯洞穴,一個非常特別的發現。我們真的在這裏看到了東西,就好像它昨天被放在這一樣。

旁白:

當他們在洞穴中挖掘時,他的團隊正回到數萬年前人類居住的遠古時代。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

我們來到這一層面,你可以看到這裏,這是非常了不起的。表面上躺著最漂亮的人工制品,骨頭點,矛尖,我立刻意識到我們已經走了很遠很遠的路。

旁白:

這些精美的工藝品早在人類革命之前就有七萬多年的曆史了,但仍然沒有證據證明洞穴裏的人是像我們這樣有思想的人。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

你總是希望並且認為,也許有一天你會找到一些確切的證據,告訴你這些人是現代人。我們是否會在這種環境中找到藝術,這些人甚至會制作藝術品嗎?我們不知道,我們根本不知道。

旁白:

然後有一種物品一遍又一遍地出現。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

我們注意到大量的赭石。赭石是一塊軟石頭,有紅色和黃色。如果你刮掉它,它就會產生粉末,這種粉末可以和動物脂肪混合,用作塗料。

旁白:

起初,沒有人能算出在洞裏的赭石能在幹什麼。這不是自然發生的。事實上,它來自數英裏之外的地方。它一定是出於某種原因被帶到那裏的,但是為什麼呢?

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

我認為赭石對這些人非常重要,我們可以看到,僅僅是因為大數人都需要它。僅在古老的過去就發現有8000塊赭石。這些赭石的使用,首先他們要得到粉末,我覺得其次他們可以用赭石的顏色直接應用到其他物品表面。

旁白:

後來有一天,亨希爾伍德發現了一塊不同於其他的赭石。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

一天下午,我們在這裏挖掘,發現了另一塊赭石。我們記錄下我們拿出所有赭石的片段。我們發現了這塊赭石,刷了一邊看到這裏擁有非常顯著的圖案,你能想象不出我們是多麼地激動。

旁白:

赭石似乎是用一個清晰的圖像標記出來的,看起來像是一個抽象的幾何圖形。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

這是一種特意在每個方向上刻畫出一連串的交叉陰影線,一條橫過頭頂的線,一條穿過中間的線和一條線在下面的線,所以它實際上限制了雕刻,就好像是他們做了十字架,他們也故意把它和其他的線包圍起來。

旁白:

亨希爾伍德相信他發現了世界上有史以來最古老的藝術作品,但他必須進一步確定。它真的很古老,真的是藝術嗎?所以首先它們是很早時期的赭石。它被發現的洞穴層面有七萬七千年的曆史,是人類革命時間的兩倍。那是藝術品嗎?考古學家弗朗西斯·德埃裏克是史前標記方面的專家。他必須核實這些線條是否被刻意設計成藝術品,並不是偶然的刀痕。

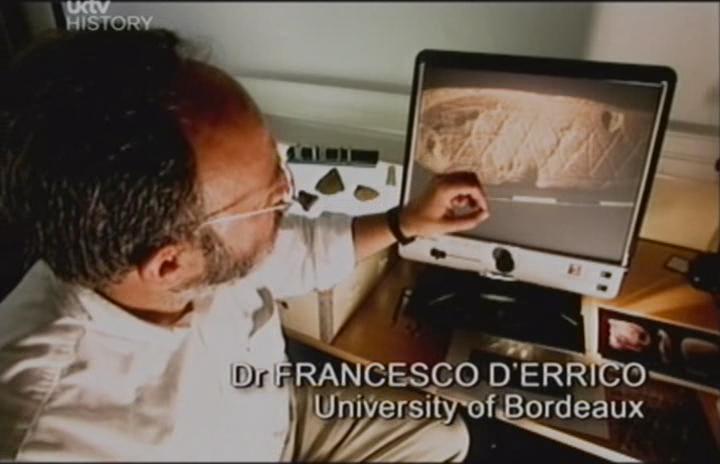

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克博士(波爾多大學):

DR FRANCESCO D'ERRICO (University of Bordeaux)

這些線條是用一個點而不是一把刀或一個切削工具產生的,因為線條在一點一點移動產生的,這些線條都有一定的上下搖擺性,所以這上面的線條是雕刻師經過深思熟慮,專門為一種目的而設計的。

旁白:

德埃裏克的分析表明,赭石板被仔細打磨後刻意雕刻。這意味著沒有更多的疑問。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

這是人類在人腦以外儲存東西能力所顯示出的第一個例子。你正在儲存信息,是其他人,他們是同一個群體的一部分,他們可以拿起,他們就會明白那意味著什麼。這就是藝術、寫作和其他一切事物的開端。

旁白:

這不是一次性的發現。亨希爾伍德發現了第二塊赭石,上面有一個類似的抽象圖案。他在布隆博斯的發現像野火一樣傳遍了科學界。

艾利森·布魯克斯(ALISON BROOKS):

我在一次科學會議上和弗朗西斯科坐在第四排和第五排,原來他口袋裏有一張這種東西的照片。他拿出這張照片給我看,我真的覺得我的頭發好像是豎立起來。這是一個確定的時刻,它不可能是任何東西,而是現代人類大腦的產物,然而卻是古老的。

旁白:

這不是一次性的發現。亨希爾伍德發現了第二塊赭石,上面有一個類似的抽象圖案。他在布隆博斯的發現像野火一樣傳遍了科學界。

艾利森·布魯克斯(ALISON BROOKS):

我在一次科學會議上和弗朗西斯科坐在第四排和第五排,原來他口袋裏有一張這種東西的照片。他拿出這張照片給我看,我真的覺得我的頭發好像是豎立起來。這是一個確定的時刻,它不可能是任何東西,而是現代人類大腦的產物,然而卻是古老的。

旁白:

布隆博斯的證據指明了一個結論:現代人類的行為並沒有在4萬年前的歐洲開始,但至少在非洲早在3萬年就開始了。人類革命理論必須是錯誤的。在布隆博斯發現之後,突然發現了非洲有許多其他令人費解的發現——從8萬年前開始的複雜石器工具;來自9萬多年前的錯綜複雜的魚叉;以及傑弗裏·萊特曼關於語言進化的研究——所有這些都被認為是思維和現代行為的標志,但現在一切都被重新考慮了。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

我們有一段時間。如果你喜歡鑲嵌圖案的話,人類思維的進化不僅僅局限於布隆博斯,而是在非洲各地不斷地湧現,不同的事情發生在不同的時間。

艾利森·布魯克斯(ALISON BROOKS):

這些行為是逐漸出現的而不是突然出現的。如果你回到13萬年前,你沒有找到整個套房,你只會找到其中的一部分。

旁白:

所以似乎沒有哪一天我們學會了思考。在歐洲發現的藝術品只是一個漫長過程的高潮,這一過程已經耗費了數十萬乃至數百萬年的時間。人類還沒有感受到上帝的遺傳影響。相反,就像自然界的其他一切一樣,思想和語言也逐漸出現,就像進化規律所說的那樣,但還有一個最終的難題仍然需要解決。如果思想在數十萬年的時間裏出現,那麼為什麼尼安德特人沒有進化出來,如果他們有,那麼為什麼他們被消滅了呢?在現代人到達歐洲之前,法國多爾多涅省佩什德拉澤(Pech de L'Aze)的洞穴是尼安德特人世代的家園。在20世紀60年代出土的所有東西似乎都符合尼安德特人作為原始物種的典型特征,不能像現代人那樣思考,但隨後克裏斯·亨希爾伍德的同事弗朗西斯·德埃裏克注意到一整套類別的證據被忽視掉了。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

這些錳元素在博物館的抽屜裏保存了30多年。(譯者注:錳被證實為6萬年前尼安德特人使用的筆)

旁白:

在洞穴的地層中發現了450塊黑色氧化錳。它是一種岩石,它的粉末可以用作顏料,就像赭石一樣,而且它似乎又被用於一個非常特殊的用途。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

其中的一些,像這個,是鉛筆的形狀。雙方一直在努力制造一個已經被磨損的點。然後把顏料塗在柔軟的表面上,我們對顏料的顯微鏡檢查顯示,這一定是在動物皮膚或人的皮膚上做的。

旁白:

如果德埃裏克是對的,而且顏料被用於制作了鉛筆,那就意味著尼安德特人一定能夠有某種形式的符號表達,某種形式的藝術。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

在這些顏料中肯定的具有某種象征性的意義,但在尼安德特人與現代人類沒有接觸的時期,這一時期與現代人類在非洲使用紅色赭石是一樣的。

旁白:

德埃裏克研究了其他證據,比如這些令人驚歎的尼安德特人制作的珠寶首飾,這些珠寶首飾證明了他們與來到歐洲的現代人類曾經並肩在一起生活過。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

這些文物是由尼安德特人制造的,由尼安德特人打磨而成,同樣也由尼安德特人使用。對我來說,這是最後一個尼安德特人能夠具有象征性思維的證據。

旁白:

換句話說,有證據表明尼安德特人可能也在思考和說話,他們甚至在遇到我們的祖先之前就已經在思考了。這些被揭露的事實意味著尼安德特人的傳統觀點是野蠻的,原始的物種正在被拋棄。這意味著它們的消失可能並不像一個高級物種的滅絕那麼簡單。相反,德埃裏克懷疑是其他的東西所起的的作用,一些更普通的和隨機的,比如疾病。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

尼安德特人的消失至今仍是個謎。由於新疾病的出現,這很可能是流行病學的原因,就像人們侵入新界時經常發生的一樣。

旁白:

這不會是曆史上第一次入侵人口導致另一個物種的意外滅絕。這是北美和南美的土著居民的命運,他們被西方人帶來的流感和天花所摧毀。也許這是一個類似的結局,在幾萬年前降臨到我們最後的人類表兄弟身上。

弗朗西斯·德埃裏克(FRANCESCO D'ERRICO):

我認為,如果尼安德特人沒有消失,他們將毫無疑問地發展出他們自己的現代行為,也許是一種與我們自己的不一樣的現代行為。

旁白:

我們對尼安德特人的描述還遠未確定,但確實有令人著迷的可能性。如果曆史發生了不同的轉變,也許尼安德特人會活到今天。這是一個非凡的想法。人類革命理論的崩潰意味著現代人類並沒有像教科書所說的那樣突然出現在歐洲。它在很久以前就開始出現在南非的布隆博斯這樣的地方。這是早在7萬多年前第一批真正的現代人生長的地方。

克裏斯·亨希爾伍德(CHRIS HENSHILWOOD):

我喜歡思考,當人們住在這個洞穴時,他們的想法和行為。我們和7萬年前的人坐在同一個地方。他們在做什麼,他們在想什麼?我相信和我們現在正在做的事情是一樣的。他們具有象征性的思想。換句話說,他們可以談論昨天、今天和明天。這是一個了不起的進步。

The Day We Learned To Think - programme transcript

NARRATOR (JOHN SHRAPNEL):

It is one of the greatest whodunits of them all. When, in the course of our evolution from apes to modern humans, did we acquire the ability to talk, to give meaning to the world around us, to think? When did we really stop being animals and become truly human? Now one small stone may hold the answer. This piece of ochre could at last solve a 100,000 year old mystery, the mystery of the day we learned to think. Hidden on the wild coast of South Africa where the Indian Ocean joins the Atlantic, there is a cave. Today it's abandoned, but once it teemed with life. For here, tens of thousands of years ago, some of our earliest ancestors lived.

PROF CHRIS HENSHILWOOD (African Heritage Research Institute):

I like to think of areas along this coast as being the original Gardens of Eden. You really had everything that you needed.

NARRATOR:

For the last 10 years this cave has been anthropologist Chris Henshilwood's life. Every year he's dug further and further down back into time searching for clues about the people who lived here and one day he came across something he never expected to see, something that, according to all the textbooks, just shouldn't have been there at all.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

This absolutely incredible image appeared. There was enormous excitement as you can imagine. Everybody was jumping around the place. Here was a definitive image that nobody would argue with was deliberately created.

NARRATOR:

Henshilwood's discovery is threatening to revolutionise our understanding of one of humanity's biggest puzzles. History books may have to be rewritten and long-held theories torn up. Because of what he found one of the great scientific detective stories may finally have been solved: when did our ancestors cease being brute animals and first become truly human? When did we learn to think? Thinking is the defining trait of humankind. It has given us machines, technology, power. No other animal has the ability to look at the world outside and transform it. Thinking makes us what we are - the most dominant species to have ever strode the earth. Where all other animals live from day to day we alone plan ahead, dream and create.

PROF RICHARD KLEIN (Stanford University):

Well I suppose if I had to isolate one trait that I would say marks modern humans, its innovativeness, creativity, the ability to introduce and invent new things all the time. No other animal species is continually reinventing its own behaviour.

NARRATOR:

Prof Richard Klein believes art is a landmark in human evolution. Unquestionable art that's widespread and common suggests you're dealing with people just like us. No other animals, after all, are able to define a painting as anything other than a collection of colours and shapes. This ability is unique to humans. But when did this crucial ability to be creative and to dominate the world around us actually happen? Find the day we learned to think and you would have identified perhaps the single most important moment in human history.

Other scientists agree. They believe art defines humans as behaviourally modern, and its beginning must coincide with the ability to speak and use language. If someone has the imagination to devise a shared way to describe their environment using art then it seems inconceivable that they could not possess language and speech. The search for the moment our ancestors became behaviourally just like us is also the hunt for the first evidence of art.

PROF ALISON BROOKS (George Washington University):

We essentially live in a world that we create in our heads. If you look around us everything that you live in is created by humans. This is a fascinating development. How do we come to behave the way we did? When did this happen?

NARRATOR:

The search for the answer to that question has become one of science's greatest missions, but it was not going to be simple. Thinking leaves no traces. There are no fossilised thoughts waiting to be dug out of the ground and dated. It was like investigating a murder scene without a body. So scientists had to look for indirect clues - not fossils, but other evidence for when thought began and then they realised that thought must have come hand-in-hand with something else.

MONTAGE MAN:

Come on, four pound a pound banana... WOMAN: Oh yes, I tried to speak to her yesterday. WOMAN: Yes, did you not... WOMAN: No, I didn't know...

NARRATOR:

Thinking also means talking.

MAN:

Give me a few...

NARRATOR:

For us to be able to transform the world our thoughts need communication.

WOMAN:

Thanks very much, thank you...

NARRATOR:

So scientists concluded thinking could only have happened when we developed language.

MONTAGE MAN:

...utterly vacuous. MAN: ...make a simple mistake. MAN: ...some day he discovered mobiles...

GEORGE BUSH:

Read my lips.

PROF RANDALL WHITE (New York University):

Language, it's really a critical threshold to cross. The ability to have things stand for other things and to recognise and to agree within a culture or, or even within a species that a certain thing stands for something, something else.

NARRATOR:

But then archaeologists ran into the same problem all over again. There are no ancient tape-recordings and writing was only invented recently.

ALISON BROOKS:

What are we going to look for? First of all it's going to give us evidence that humans were behaving in a modern way.

MAN:

...the high esteem in which she's held.

ALISON BROOKS:

We're very stumped for how we're going to get evidence of these kinds of things, so we look in a way for proxies.

NARRATOR:

But there was one kind of evidence archaeologists could look for, something that was proof of thought and as clear a form of language as you could ever hope to see.

RICHARD KLEIN:

How do we detect creativity in the, in the archaeological record? One obvious line of evidence is art. When you get unquestionable art that's widespread and common I think you could say that you're dealing with people just like us.

NARRATOR:

Only humans create, and can make sense of, art.

PROF TERRENCE DEACON (University of California, Berkeley):

I'm sure that dozens of dogs have walked down this street in the past years and perhaps not one has glanced up in awe or wonder and thought to himself what does this mean? For a dog this is colour on a wall, perhaps even less than that.

NARRATOR:

But to a human being a painting is far more than just a collection of colours. It is a language, an expression of thought.

TERRENCE DEACON:

In a lot of ways this becomes a way of talking. This is a story. In fact many, many stories. The listener, the reader, the onlooker has to decode the story, so when you look at this mural and see all of these different images you don't look at these for the pictures, you don't look at these for the colour, you don't look at these for what they do to the building, you look through them to meaning.

NARRATOR:

For archaeologists this realisation that art, language and thought were all the same thing was a huge breakthrough. Suddenly what they had to look for was clear. Discover the earliest forms of human art and you would have found the day we learned to think. So starting decades ago archaeologists went hunting for art. They looked in the obvious place: Africa, the cradle of human evolution itself, but they found nothing. They traced the path the early humans took out of Africa through the Middle East. Still nothing. So archaeologists turned to Europe and then a wonder- the first ever cave paintings, stunningly crafted and detailed.

RANDALL WHITE:

This is their representation of the world around them, so when I walk into one of these caves it just, absolutely gives me chills to think that in some miniscule percentage I'm able to actually peek into the way that they saw their world. We can walk into a cave like that and say I understand, I understand the mystery. A modern human would have done that, I would have done that.

NARRATOR:

And they found far more: intricately worked statuettes; thousands of pieces of jewellery. Here at last in Europe was the evidence archaeologists had been searching for - symbolic art that could only have been made by people who could talk and think, like us, and it all dated from the same period - around 35,000 years ago. The European evidence was beyond doubt. It was as if a light bulb had gone on inside the human brain, a thinking Big Bang. For some reason we'd suddenly become truly modern humans.

RANDALL WHITE:

All of the elements of the human mind were in place to create everything that exists subsequently - to go to the Moon, to create writing, to create agriculture, to do all of the things that we've done over the subsequent 35,000 years.

NARRATOR:

And so, it seemed, the moment we'd learned to think had been found. This landmark moment in human history became known as the Human Revolution. Just how powerful this Human Revolution must have been was shown by something else, something more disturbing. For when our ancestors first arrived in Europe 35,000-40,000 years ago there were people already waiting for them, another species of human who'd been living in Europe for hundreds of thousands of years. They were called the Neanderthals.

PROF JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN (University of Bordeaux):

It's difficult for us to, to accept, even to understand this notion of different species of humans living in the same world. Very, very strange.

NARRATOR:

The Neanderthals were as much a part of the human family as we are, closer to us thaen any living animal like chimpanzees, but because they'd come out of Africa long before our immediate ancestors they had evolved along very different lines.

JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN:

The face of a Neanderthal is a very long face and it's also very projecting in the middle portion of the face. It's very likely that Neanderthals had very big and very projecting nose. That was probably a very spectacular feature.

NARRATOR:

The Europe the Neanderthals had made their home had been wracked by a succession of Ice Ages. It was a punishing environment and one which shaped their whole physical appearance.

JEAN-JACQUES HUBLIN:

They have long trunk and rather short limbs which is something which allows to retain some warmth in the body. I would say they look a little bit like Eskimos. They were very well adapted to this very challenging and very changing environment, but about 40,000 years ago something happened to them that never happened before.

NARRATOR:

What happened was the arrival of the modern humans. After 250,000 years of life the Neanderthal species was wiped out almost overnight. For scientists the arrival of the modern humans and the disappearance of the Neanderthals had to be more than a coincidence. The first clues to understanding what might have happened emerged when they studied Neanderthal tools.

RANDALL WHITE:

When you're confronted with certain aspects of Neanderthal, of the Neanderthal archaeological record you scratch your head because you say I don't understand, I wouldn't have done it that way, why didn't they do it this way?

NARRATOR:

Neanderthal tools were very different to ours in one crucial respect: everything was much simpler and above all, unlike the modern humans, there was no Neanderthal art and so no evidence these primitive humans could actually think.

RICHARD KLEIN:

Neanderthals don't seem to have produced anything that we would really call art. They don't seem to have produced personal ornaments. They were in fact truly primitive people. Sure they were human, they just weren't modern human.

NARRATOR:

And so archaeologists put together a theory to explain their disappearance. 40,000 years ago modern humans arrived in Europe and suddenly started to think. This gave them a unique advantage over the Neanderthals. In the battle for the scarce resources left by the Ice Age brains won out over brawn as our superior minds allowed us to defeat our physically tougher neighbours.

RANDALL WHITE:

One population capable of communicating better, capable of inventing better, capable of organising better in the face of a population that had none of that in their 300,000 year tradition. It seems to me that the, the competition would not have lasted very long.

NARRATOR:

Unable to think like us the apparently inferior Neanderthals were pushed to the brink of extinction until, finally, they vanished altogether. This then was the final proof of the power of the Human Revolution. That sudden dawning of thought had allowed us to surpass even our nearest relatives. The Human Revolution had given us the power to take over the world. But then the mutterings started. A strange anomaly emerged that didn't quite fit with the Human Revolution story. It began when scientists started looking for the first traces of that other supposed proof of thinking, not art but language. It was Jeffrey Laitman who started the confusion. He's an expert in anatomy and in particular one small part of the human body, the part we use to speak: the throat.

PROF JEFFREY LAITMAN (Mount Sinai School of Medicine):

The throat is arguably the most important region in all of human anatomy and physiology. As a native New Yorker I like to think of this as the Grand Central Station of the human body. (Background voice) These are really nice. This is a really clear picture...

NARRATOR:

Laitman began studying the human voice box, or larynx. He discovered that in the course of evolution our larynx had moved to a very different position to that of all other mammals.

JEFFREY LAITMAN:

Something has happened in you and me and what's happened has been rather remarkable. Our larynx has descended in the throat. One key gain, of course, is that by the larynx being lower in the throat you have space above it, so what we get in the deal is a mechanism which has turned us, sound-wise and turned us vocal-wise from being a, a bugle to being a trumpet. (Background voices) Around the... Which one am I following (TALKING TOGETHER) Beautifully here, beautifully...

NARRATOR:

What the lower larynx gives us is the ability to speak.

(Background voice) ...the upper lip is over here. Right, you can see it clearly on the...

NARRATOR:

So Laitman started to wonder: when did this lowering of the larynx actually happen, when did we acquire this ability to speak? His research revealed that over the course of millions of years of evolution the shape of our skulls had changed in a way that had caused the larynx to descend.

JEFFREY LAITMAN:

The big difference is when you find adult humans. When you look at the bottom of their skulls you see a little valley, a gully, which is very different and the relationship we found were that skulls that are very bent bottom, like this, relate to a larynx not positioned high on up, but a larynx that has gone much further down.

NARRATOR:

The gully-shaped skull went hand-in-hand with the ability to speak, so Laitman began to investigate. When had this key development needed for language actually happened? Looking at skulls from further and further back in time he found something deeply puzzling.

JEFFREY LAITMAN:

By the time of early members of our own species, Homo sapiens, some 100,000-200,000 years before the present, we start to see features that are almost identical to living humans.

NARRATOR:

The modern gully shape and so the ability to speak had been reached at least 200,000 years ago, long before the Human Revolution.

JEFFREY LAITMAN:

So they had the anatomy for it. Were they speaking like us? Now we get into the world of hypothesising. I wasn't there. However, if you have a car that has a nice, big engine and all the tyres you assume that car is going to run and it's going to run pretty fast otherwise why does it have that big engine and why does it have all those nice tyres? That's what we're dealing with.

NARRATOR:

And then in Israel something happened to thicken the plot even further. In 1989 an archaeological site yielded for the first time a tiny and precious piece of a Neanderthal skeleton called the hyoid bone.

DR MARGARET CLEGG (University College London):

The hyoid bone is a bone in your vocal tract and it sits about here and if you press with your fingers you can actually feel the shape of the bone.

NARRATOR:

Just as in modern humans the Neanderthal hyoid would have been crucial in forming the larynx. For the first time scientists could compare our ability to make sounds with the Neanderthals and they were in for a surprise. The hyoid bones were virtually identical.

MARGARET CLEGG:

The relationship between the hyoid bone and the cranial base and the face and the skull is the same in the Neanderthals as it is in modern humans and the implication of that is that the hyoid bone is going to sit in the same place as it does in modern humans. It's going to be low in the throat.

NARRATOR:

In other words, like modern humans the Neanderthals had a low larynx. It meant they too would have been physically capable of speech. In fact in some ways they might even have done it better.

MARGARET CLEGG:

The thing about the Neanderthals is that although they would have had a similar sort of vocal tract to ours there were differences in the Neanderthals. They've got great big chests, they've got huge noses and massive sinuses. Now the big chest and large nose is going to give them a much bigger sound, much more in common, perhaps, with an opera singer than with an ordinary person.

NARRATOR:

There was now a clear paradox. The Human Revolution theory said we only learned to think 40,000 years ago and the proof of that was the sudden appearance of art in Europe, but according to the fossils that other apparent proof of thought, speech, had emerged 160,000 years earlier. It just didn't make sense.

RANDALL WHITE:

That raised a serious question for us archaeologists, it raised a serious question because it said OK, you can have anatomically modern humans in Africa 100,000 years ago, but why if they're anatomically modern aren't they doing all this good stuff that we see among the earliest moderns in Europe, why are, why aren't there painted caves, why aren't there all of these engraved objects etc?

NARRATOR:

For supporters of the Human Revolution theory, like Richard Klein, there was now a real difficulty. How to reconcile the contradictory evidence of the art and the anatomy, so Klein proposed a radical theory. Even if humans had the anatomy for speech much earlier they didn't have the ability to use it. Then, in contrast to every other process in evolution, where change happens gradually, the human mind had been switched on suddenly through a single, freak genetic mutation. Only then did we start to think, to talk and to create art.

RICHARD KLEIN:

I think that what happened 40,000 or 50,000 years ago was that there was a genetic mutation that allowed people to be very much more creative than they had been before, to think differently, to ask questions about what if I make my tools this way, what would be the result, in a way that no one had been able to do before.

NARRATOR:

According to Klein thought had not emerged through gradual evolution, but in a sudden, dramatic leap forward. It was as if we'd been genetically touched by God. For Klein this sudden awakening was so powerful it was the only possible explanation for why we'd replaced the Neanderthals. We had the thinking genes and they didn't.

RICHARD KLEIN:

My belief is yes, there were genes missing, if you like that made it impossible for them to behave in a fully modern way and that helps us to understand why when modern humans appeared in Europe beginning perhaps 40,000 or 45,000 years ago they were able to replace the Neanderthals so completely.

NARRATOR:

It was a bold hypothesis and a compelling one. The Human Revolution theory remained the best explanation of the day we learned to think. But then, in the year 2000, on the other side of the world from Europe, in Africa, came something utterly unexpected. At Blombos, on the east coast of South Africa, anthropologist Chris Henshilwood had been quietly excavating his prehistoric cave for over a decade.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

This is Blombos cave, a very special find. We're really looking at what has been left here almost as if it was put down yesterday.

NARRATOR:

As they dug down through the floor of the cave his team were going back to an ancient time of human habitation tens of thousands of years ago.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

We came down onto this layer you can see over here which really was quite remarkable. On the surface were lying the most beautifully made artefacts, bone points, spear points as well and immediately I realised we'd gone back a very, very long way in time.

NARRATOR:

The beautifully crafted objects were dated to over 70,000 years ago, long before the Human Revolution, but there was still no proof the people in the cave were thinking people, like us.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

You always hope and think that perhaps one day you will find some really definitive evidence that'll tell you these people were modern. Are we going to find art in this environment, did these people even produce art? We didn't know that, we had no idea at all.

NARRATOR:

Then one type of item started appearing over and over again.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

We noticed large numbers of pieces of ochre. Ochre is a soft stone, comes in reds and yellows. If you scrape it it'll produce a powder and that powder can be mixed with animal fat, for example, and used as a paint.

NARRATOR:

At first no one could work out what the ochre was doing in the cave. It didn't occur there naturally. In fact, it could only have come from miles away. It must have been brought there for a reason, but why?

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

I think ochre is very important to these people and we can see that simply because of the great numbers. 8,000 pieces of ochre in the old levels alone. They have scraped these pieces of ochre to, first of all, obtain the powder and I think secondly, so they could use the ochre to apply colour directly to other surfaces.

NARRATOR:

Then one day Henshilwood found a piece of ochre that was different from the rest.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

One afternoon we were excavating here we found another piece of ochre. We'd been recording all the pieces of ochre we'd taken out. We found this piece of ochre, brushed up the side and there was this absolutely remarkable pattern revealed. There was huge excitement you can imagine.

NARRATOR:

The ochre piece appeared to have been marked with a clear image, what seemed like an abstract geometric pattern.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

This was a deliberate construction of a series of cross-hatchings in each direction, a line across the top, a line through the middle and a line down the bottom, so it actually circumscribed that engraving as if it was they'd made the crosses and they'd deliberately surrounded it with these other lines as well.

NARRATOR:

Henshilwood believed he'd found what was possibly the world's oldest ever work of art, but he had to be sure. Was it really that old and was it really art? So first they dated the ochre. The cave layers it was found in showed it to be 77,000 years old, twice as old as the Human Revolution. Then was it art? Archaeologist Francesco d'Errico is a specialist in prehistoric markings. He had to verify whether the lines were deliberately created to form a work of art and were not accidental knife marks.

DR FRANCESCO D'ERRICO (University of Bordeaux):

These lines were produced with a point rather than a knife or a cutting tool because there is movement, there is a certain wobbly character to the line, so the lines on the piece are the results of a deliberate series of actions by the engraver with a tool specially designed for that purpose.

NARRATOR:

D'Errico's analysis showed the slab of ochre had been specially rubbed down before being carefully, and deliberately, engraved. It meant there could be no more doubt.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

Here is the first example of the ability of humans to store something outside the human brain. You are storing the message that somebody else, who's part of that same group, could pick up and they would understand what that meant. This is the beginning of things like art, writing and everything else that follows.

NARRATOR:

And this was no one-off find. Henshilwood found a second slab of ochre with a similar, abstract pattern. His discoveries at Blombos spread like wildfire through the scientific community.

ALISON BROOKS:

I was at a scientific meeting and Francesco, who was sitting in the fourth or fifth row, turned out to have a photograph of this thing sort of in his pocket. He pulled out this photograph and I, I really felt as if my hair stood on end. It was like a definitive moment to see it. It couldn't be anything but the product of a modern human brain and yet it was old.

NARRATOR:

The evidence of Blombos pointed to one conclusion: modern human behaviour had not started in Europe 40,000 years ago, but in Africa at least 30,000 years earlier. The Human Revolution theory had to be wrong. In the wake of the Blombos finds suddenly a whole host of other puzzling discoveries in Africa made sense - sophisticated stone tools that dated from 80,000 years ago; intricate harpoon points from over 90,000 years ago; and Jeffrey Laitman's research on the evolution of speech - all had been dismissed as signs of thinking and modern behaviour, but now everything is being reconsidered.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

We've a period. a mosaic if you like, of the evolution of the human mind that is not just focussed on Blombos, but spread across Africa and different things are happening at different times.

ALISON BROOKS:

There's a very gradual emergence of these behaviours rather than a sudden appearance of all of them. If you go back 130,000 years ago you don't find the whole suite, you only find part of it.

NARRATOR:

So it seems there was no single day we learned to think. The art found in Europe was just the culmination of a long process that had taken hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years. Human beings had not been genetically touched by God. Instead, like everything else in nature, thought and language had emerged gradually, just as the laws of evolution said they should, but there was one final puzzle that still needed to be solved. If thought had emerged over hundreds of thousands of years then why hadn't the Neanderthals evolved it too and if they had, then why had they been wiped out? The cave of Pech de L'Aze in France was home to generations of Neanderthals before the arrival of the modern humans in Europe. Excavated in the 1960s everything found here seemed to fit the typical picture of the Neanderthals as a primitive species, incapable of thinking like the modern humans, but then Chris Henshilwood's colleague, Francesco d'Errico noticed a whole class of evidence had been overlooked.

FRANCESCO D'ERRICO:

These pieces of manganese have remained in museum drawers for more than 30 years.

NARRATOR:

450 pieces of black manganese oxide had been found in the layers of the cave. It's a rock whose powder can be used as a pigment, just like ochre, and again it seemed to have been used for a very particular purpose.

FRANCESCO D'ERRICO:

Some of the pieces, like this one, are in the shape of a pencil. The two sides have been worked to produce a point which has been worn down. The pigments were then rubbed on a soft surface and our microscopic examination of the pigments show this must have been done on either animal skin or on human skin.

NARRATOR:

If d'Errico was right and the pigment was used as a pencil it meant the Neanderthals must have been capable of some form of symbolic expression, some form of art.

FRANCESCO D'ERRICO:

Some of these pigments must have been used symbolically, but from a period when the Neanderthals were not in contact with modern humans, a period which was the same as when red ochre was being used by modern humans in Africa.

NARRATOR:

And d'Errico examined other evidence, like these stunning pieces of Neanderthal jewellery that dated from the time they were living side-by-side with modern humans.

FRANCESCO D'ERRICO:

These objects were made by the Neanderthals, polished by the Neanderthals and equally worn by the Neanderthals. For me this is the proof the last Neanderthals were capable of symbolic thought.

NARRATOR:

In other words, the evidence suggested that the Neanderthals may have been thinking and speaking too and they might have been doing it even before they met our ancestors. These revelations have meant the traditional view of the Neanderthals as a brutish, primitive species is being discarded. It means their disappearance may not have been as simple as the extermination of an inferior species by a superior one. Instead, d'Errico suspects something else may have been at work, something more mundane and random, like disease.

FRANCESCO D'ERRICO:

The disappearance of the Neanderthals is still today a mystery. It could well be for epidemiological reasons due to the arrival of new illnesses, as has often happened when people invaded new territories.

NARRATOR:

It would not have been the first time in history one invading population had led to the accidental extinction of another. It was the fate of the North and South American native peoples, devastated by 'flu and smallpox, brought in by Westerners. Perhaps it was a similar end that befell our last human cousins tens of thousands of years earlier.

FRANCISCO D'ERRICO:

I think that if the Neanderthals had not disappeared they would have no doubt developed their own kind of modern behaviour, perhaps of a kind not so different from our own.

NARRATOR:

Our picture of the Neanderthals is still far from definite, but it does raise a fascinating possibility. Had history taken a different turn perhaps the Neanderthals would have survived to be living amongst us today. It's an extraordinary thought. The collapse of the Human Revolution theory means that modern humanity did not suddenly arise in Europe as the textbooks once said. It began to emerge slowly long ago in places like Blombos in South Africa. This is where the first truly modern humans grew up over 70,000 years ago.

CHRIS HENSHILWOOD:

I like to think about what the people must have thought and done when they lived at this cave. We sit in the same place those people sat 70,000 years ago. What were they doing, what were they thinking? I believe very much the same as we're doing right now. They were capable of symbolic thought. In other words, they could talk about yesterday and today and tomorrow. That is a remarkable step forward.

(文字来自:BBC Home Science & Nature Horizon)

文字:《傑特遜工作室》(JENTSON STUDIO) 制作

視頻:《傑特遜工作室》(JENTSON STUDIO) 紀錄片數據庫BBC-021號

翻譯:趙永安