Labour-monitoring technologies raise efficiency—and hard questions

Pushing back against controlling bosses leaves workers more likely to be replaced by robots

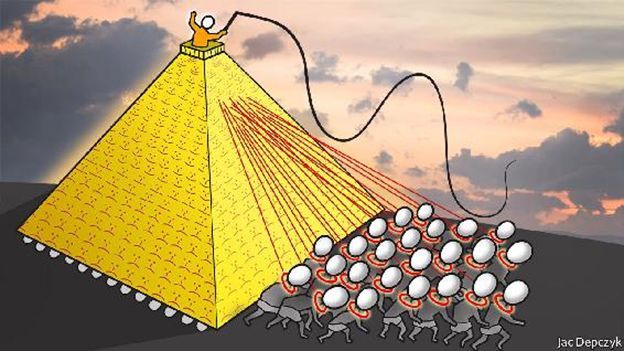

BOSSES have always sought control over how workers do their jobs. Whatever subtlety there once was to this art, technology is now obliterating. In February Amazon received patents for a wristband apparently intended to shepherd labourers in its warehouses through their jobs with maximum efficiency. The device, were Amazon to produce and use it, could collect detailed information about each worker’s whereabouts and movements, and strategically vibrate in order to guide their actions. Using such technology seems an obvious step for firms seeking to maximise productivity. Whether workers should welcome the trend, or fear it, is harder to say.

Workplace discipline came into its own during the Industrial Revolution. As production came to depend ever more on expensive capital equipment, bosses, not keen to see that equipment sitting idle, curtailed their workers’ freedom, demanding they work during set hours, in co-ordination with other employees, at a pace dictated by the firm. Technology creates new opportunities for oversight. Editors can see which of their journalists attract the most readers (though many wisely focus on other measures of quality). Referees at sporting events are subject to reviews that check their decisions to within millimetres.

obliterate: to destroy (something) completely so that nothing is left

老板或者资本家就是希望他们的员工努力的干活,为了监控他们是否努力干活,科技手段就很重要了,亚马逊出了一个专利手带,检测仓库里的员工动态,在哪里,晃动的频率等!

Workers and labour activists have often attacked strict discipline as coercive, unfair and potentially counterproductive. Textbook economics suggests, though, that in a competitive labour market any attempt to coerce people into working harder than they want will fail, since workers can simply switch jobs. Studies of factory work paint a more complicated picture, however. People would like to work hard and earn high wages, this story goes. But they struggle with self-control and do not work as hard as they wish they would. They consequently choose to work for firms that use disciplinary measures to push them. During industrialisation,workers “effectively hired capitalists to make them work harder”, says Gregory Clark of the University of California, Davis, in a seminal paper on the subject.

If that seems an implausibly sunny description of life in 19th-century factories, researchers have found evidence for such behaviour in modern contexts. Supreet Kaur, of Columbia University, and Michael Kremer and Sendhil Mullainathan, of Harvard University, ran a13-month experiment using data-entry workers, who were paid according to the amount of work successfully completed. Some struggled with self-control, the authors determined, as shown by their tendency to slack off for much of each month but put in more effort as payday approached. When workers were offered contracts that penalised them for failing to hit performance targets, those who struggled to stay on-task disproportionately accepted, and achieved big gains in output and pay as a result.

coercive: using force or threats to make someone do something

slack: to give little or no effort or attention to work

In many settings, pay is less clearly linked to performance. Whether additional effort translates into higher wages depends on the other options available to workers and on their bargaining power—in particular, whether they feel able to leave if the pay is not worth the trouble. Indeed, in the past, high turnover helped motivate some factory owners to share the gains from workplace discipline with workers. The “$5 day” introduced by Henry Ford in 1914 was an “efficiency wage”, according to Daniel Raff, of the University of Pennsylvania, and Larry Summers, of Harvard University. Workers on Ford’s assembly lines spent entire shifts doing mind-numbingly repetitive work, and many could not stick it for long. Ford’s solution was to pay a wage well above what workers could earn elsewhere. That helped compensate them for their suffering. More important, it led to a long queue of eager applicants, and the knowledge that anyone who left would quickly be replaced and could not easily return.

But high turnover does not appear to bother Amazon much. The past decade’s weak labour markets have meant queues of willing workers even without the promise of above-market pay. The same technologies that monitor workers can also reduce the training time needed to prepare new employees, since the gadgets around them guide most of their activity.

And new disciplinary technologies create an additional risk for workers. Heaps of data about their activities within a workspace are gathered, while their cognitive contribution is reduced. In both ways, such technologies pave the way for automation, much as the introduction of regimentation and discipline in factories facilitated the replacement of humans by machines. The potential for automation increases the power of firms over workers. Anyone thinking of demanding higher pay, or of joining a union in the hope of organising to grab a share of the returns to increased efficiency, can be cowed with the threat of robots.

福特公司为了留住工厂流水线员工,给出了比平均市场工资要高的薪水,这一举措让来应聘的申请者众多,尽管他们要在流水线上干重复的劳动,一个员工走了立马有人替上,辞职的员工就再难回来了,因为位置被占了!

cow: to make someone too afraid to do something: intimidate

Who watches the watch, man

White-collar workers are not spared oppressive bosses. Indeed, as the New York Times reported in 2015, Amazon has experimented with data-driven management techniques known to drive some white-collar workers to tears. (Others, though, told the Times that they thrived at Amazon, “because it pushed them past what they thought were their limits”.)

The high pay of workers with exacting jobs in finance or technology can reasonably be seen as compensation for their burdensome working conditions. And unhappy professionals can usually find less oppressive work that pays a lower but still decent wage. As Amazon and other firms embrace new tools to monitor and direct their workers, the difference between progress and dystopia comes down to whether workers feel comfortable demanding raises, and whether they can quit without fear of serious hardship.Indeed, firms could ponder such matters themselves before the inevitable backlash.

oppressive: very cruel or unfair

ponder: to think about or consider (something)carefully

白领工人们也没有被老板们放过,亚马逊的数据驱动型管理技术让这些白领们工作到哭,也有人称他们在被推着超过他们认为自己的极限!

总结:天下打工的都一样,被人推着干,被人管着干,努力成为老板才是关键~

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Results

Lexile®Measure: 1200L - 1300L

Mean Sentence Length: 19.89

Mean Log Word Frequency: 3.16

Word Count: 895

这篇文章的蓝思值是在1200-1300L, 是经济学人里中等难度的

使用kindle断断续续地读《经济学人》三年,发现从一开始磕磕碰碰到现在比较顺畅地读完,进步很大,推荐购买!点击这里可以去亚马逊官网购买~