【导读】作为一段特定历史的产物,日本的朝鲜人学校,渐渐地在时代大势中失去立足之地。

North Korean schools in Japan:

日本的朝鲜人学校

Class action

群起攻之

An accident of history may soon disappear

这历史中的偶然,或许很快便要消失

Jun 15th 2013 | TOKYO |From the print edition

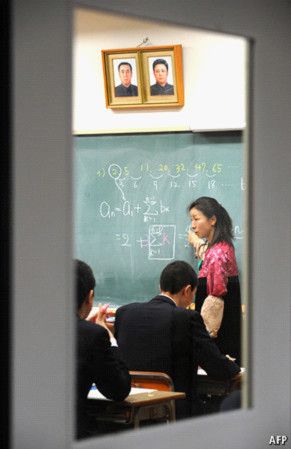

School’s out

学校一景

A TOKYO schoolyard is an unlikely venue to find North Korea’s red star fluttering in the wind. Children inside the Tokyo Korean Middle and High School study textbooks in Korean beneath portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il. When classes end, the girls shed their traditional jeogori dresses for anonymous teenage clothes and blend back into the city.

在东京的一所学校中,似乎不太可能看到迎风飘扬的朝鲜红蓝五角星旗。不过,东京朝鲜人中学里的孩子们,却正在金日成和金正日的画像之下念着课本。等一下课,姑娘们便脱下那毫无个性的传统少年服装“赤古里”,重新融入那城市的生活。

This school and around 70 more like it in Japan are an unusual legacy of Japan’s difficult relationship with Korea. Large numbers of Koreans came or were brought to Japan during the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula between 1905 and 1945. At the end of the second world war, about 700,000 of them stayed on rather than return to their homeland, which was by then sliding into the Korean war that would split the country into two bitterly opposed states. They were stateless for 20 years until 1965 when Japan recognised South Korea, at which point Koreans in Japan could become South Korean. Those who didn’t became North Korean by default and went to North Korean schools. The schools are an accident of history, often more about continuing a connection to the homeland than about ideological indoctrination.

这所学校,以及同在日本的另70所,都是日朝之间艰难关系的非常遗产。自1905年到1945年,日本占领朝鲜半岛期间,许多朝鲜人或主动或被动地来到了日本。二战结束后,他们中大约有七十万人没有选择返乡,留在了日本。随后朝鲜战争的爆发,使得他们的祖国分裂成两个相互敌对的国家。所以这些人一直过着没有国籍的生活,直到1965年,日本承认韩国独立,使他们可以获得韩国国籍。而那些没能自动加入朝鲜国籍的便入了朝鲜人学校。这些学校是历史的偶然,更多地代表了与故土的牵连,而非为了去塑造意识形态。

Students in the North Korean schools do, however, learn that some of their ancestors were brought to Japan as wartime slave labour, and that it was Washington and its “puppet” ally in Seoul that started the Korean war. For years, Japanese critics have seen the institutions as the enemy within and fought to have them closed. Now, it looks as if that could happen.

然而,在朝鲜人学校就读的学生们却往往被告知,他们的一些先人是作为战时奴工而被掠至日本的,而且是华盛顿与其在首尔的傀儡盟友发动了朝鲜战争。许多年来,日本评论家们都将这些学校看做打入本国的敌人,并争取要关停它们。而现在看来,这好像真的会发生。

Japan’s government excluded the schools from a scheme to waive tuition fees in other schools two years ago. Shinzo Abe, the prime minister, is now focusing on public funding. Tokyo has led the way, ending its 6m yen ($63,000) annual subsidy to this Korean high school. Local authorities around Japan are following suit. “We’ll survive, but many won’t,” laments the headmaster, Shin Gil-ung.

两年前,日本政府将这些学校从免学费计划的院校名单中排除。首相安倍晋三现正忙于为减免计划寻求财政补贴。东京都身先士卒,取消了对这所朝鲜人中学600万日元(63000美元)的年度补贴。各地方政府也纷纷效仿。“我们能坚持下来,但其他的那些就不一定了。”朝鲜人学校校长申吉安(音)哀叹道。

The funding assault is part of what may be the end-game in a low-level war between Japanese conservatives and the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan, known as Chongryon. The organisation, which runs the schools, is North Korea’s de facto embassy and is suspected of involvement in the North’s bizarre abduction of over a dozen Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 1980s. The Japanese want the surviving citizens returned. The North Koreans say they are all dead.

断供资金,是日本的保守派与在日本朝鲜人总联合会——俗称总联——之间暗战收尾的一部分。这个组织运营着这些学校,并且是事实上的朝鲜大使馆。它被怀疑参与了七八十年代那些奇异的绑架事件,受害者包括十几位日本公民。日方要求幸存的受害者回国。朝鲜称他们全已死亡。

Since failed attempts at normalising ties in 2002 and 2004, and a string of nuclear tests by North Korea, relations have turned toxic once again. The association’s headquarters in central Tokyo has been seized by the government-backed Resolution and Collection Corporation in an attempt to collect outstanding loans of nearly 63 billion yen. A private attempt this month by a Buddhist temple to buy the headquarters failed, amid allegations of government pressure.

由于2002年至2004年间的邦交正常化工作失败,并且朝鲜又实施了一系列核试验,所以双边关系已然又一次严重恶化。拥有政府背景,并追讨其630亿日元未尝贷款的日本清盘与托收公司,已经将东京市中心的总联总部查封。在政府的压力下,一所寺庙也放弃了买下这座总部大楼的个人努力。

The schools and the community they serve are in deep trouble anyway. Thousands of Koreans are abandoning their ethnic identities to take Japanese citizenship. Enrolment at Mr Shin’s school has fallen to 600 students from a high of 2,300 when he attended in the late 1960s. Parents pay for 80% of the institution’s costs; cash from North Korea, once a lifeline, has dried up.

总之,总联所营的学校与社团是有麻烦了。数以千计的朝鲜人放弃了种族身份,加入日本国籍。申先生的学校里,登记入学的人数,也从六十年代晚期他初来此时的2300多人下滑到如今的600人。家长们承担了80%的学校经费;而曾经的生命线——来自朝鲜的资助,已然枯竭。

Ethnic Koreans in Japan, who have grown up in a society that distrusts them, struggle with profound identity issues, says Sonia Ryang, a graduate of a North Korean school in Japan, and now a professor of anthropology at the University of Iowa. Many dislike the regime in Pyongyang but remain loyal out of respect for their parents or the desire to preserve their heritage.

在一个对他们充满不信任的社会中生长起来的朝鲜侨民,会陷入深层次的身份认同问题,曾经是在日朝鲜人学校的毕业生梁松亚(音)如是说。他如今是爱荷华州立大学的人类学教授。许多侨民厌恶平壤政权,但由于尊崇长辈,并希望继承遗产,他们仍选择忠于朝鲜。

The education minister, Hakubun Shimomura, said recently that, given the lack of progress on the abduction issue, people “will not understand” continued public funding for such schools. Ms Ryang is blunter about their future: “If you were to just leave Chongryon alone, it will die off in three years.”

文部科学大臣下村博文最近称,鉴于绑架问题没有进展,民众“将不会理解”为这些朝鲜人学校继续提供财政补贴。而梁先生对他们的未来坦白道:“如果都不管总联的话,那三年内总联就会慢慢消失了。”

From the print edition: Asia