思维导图

本篇文章来源于2018.6.30经济学人Science and technology版块。

译文为参考译文。

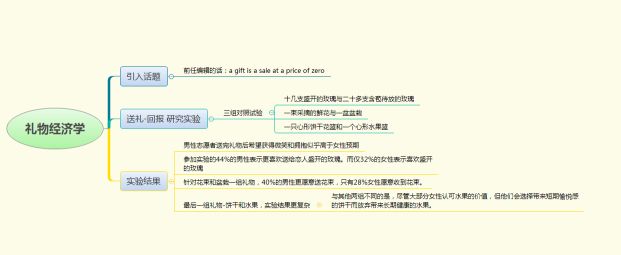

The economics of gifts

Presents of mind

A paradoxat the heart of gift-giving

A FORMEReditor of this newspaper once said that“a gift is a sale at a price of zero”. In strict monetary terms this is true. But most people do expect to be paid for gifts, albeit in the non-monetary currency known as “gratitude”. This has many denominations: words of appreciation, hugsand kisses and, particularly, smiles. The wider point our ex-editor was making, though, is pertinent. A gift will cause a misallocation of resources if the recipient would have preferred something else that would have been no more expensive for the donor to acquire.

In this context, a study just published in Psychological Science, by Adelle Yang at the National University ofSingapore and Oleg Urminsky at the University of Chicago, looks illuminating. Dr Yang and Dr Urminsky have studied the currency of gratitude and think it may be creating poor incentives. Their hypothesis is that the reason gift-givers sometimes appear to make bad decisions (that is, choose gifts the receiver would not have chosen him or herself) is not always that they do not know what the recipient wants. Sometimes it is that the receiver rewards the giver with signals of gratitude that do not seem to correspond with a gift’s long-term utility.

To test this idea, Dr Yang and Dr Urminsky framed an experiment around St Valentine’s day. They picked three pairs of appropriate gifts: a dozen roses in full bloom versus two dozen rose buds that wereabout to blossom; a bouquet of freshly cut flowers versus a bonsai; and a heartshaped basket of biscuits versus a similar basket of fruit. In each pair they hypothesised that the first, with its immediate visual appeal, strongscent orflavour, was more likely to induce a powerful appreciative response in the recipient but that the second, because of its greater quantity, durability or wholesomeness, was likely to be more satisfying in the long term. They also checked that these beliefs were not mere personal prejudice by confirming them with 104 volunteers recruited online.

They then recruited a further 295 online volunteers on February 13th, the day before St Valentine’s, in order to catch people in an appropriate mood for the experiment. Volunteers were required to be in a romantic heterosexual relationship and were paid $2 each to evaluate the pairs of gifts. Men were asked which of each pair they would prefer to give to their inamorata. Women were asked which they would prefer to receive. Both sexes were also asked to predict how much ofan “affective reaction”, as psychologists label such things as smiles and hugs, the receiver would show in response to a particular gift and which would create the greater longterm satisfaction.

As far as affective reaction and satisfaction were concerned, this second group of volunteers agreed with the first group about which gifts would elicit what response. Even so, men went for the smiles and hugs more often than it would seem that women would have wished. Specifically, 44% of them said that they would prefer to give roses in full bloom while only 32% ofthe women said they preferred that gift to the two dozen buds. Similarly, with the bouquet and the bonsai, 40% of the men preferred to give the bouquet but only 28% of the women preferred to receive it. Both of these results are in line with Dr Yang’s and Dr Urminsky’s hypothesis. The case of the biscuits or the fruit, though, is more complicated. As predicted, men preferred to give the biscuits more often than women preferred to receive them. But the relevant numbers were 73% and 61%. In other words, unlike the other two cases, a majority of women did also prefer the gift with immediate, sugary appeal rather than long-term wholesomeness, despite what they had said about the longterm value offruit.

None of this, however, explains why recipients should be willing to pay more enthusiastically in the currency of gratitudedisplays for short-term pleasure rather than long-term satisfaction. Ifthe gratitude market were working correctly, buds would trump flowers, bonsais bouquets and fruit cookies. Yet they don’t. ▇

精读笔记

The economics of gifts礼物经济学

Presents of mind心灵的礼物

A paradoxat the heart of gift-giving送礼的悖论

A FORMEReditor of this newspaper once said that“a gift is a sale at a price of zero”. In strict monetary terms this is true. But most people do expect to be paid for gifts, albeit in the non-monetary currency known as“gratitude”. This has many denominations: words of appreciation, hugs and kisses and, particularly, smiles. The wider point our ex-editor was making, though, is pertinent. A gift will cause a misallocation of resources if the recipient would have preferred something else that would have been no more expensive for the donor to acquire.

本刊前任编辑曾说:“礼物也是一种交易,而价格为零”。 从严格的货币意义上来说,这种说法是正确的。但大部分人送礼时还是期望得到回报。虽然只是非货币形式— “感激”之情。这种感激有许多形式:感激的言辞,拥抱以及亲吻,特别是微笑。 就广义而言,我们前任编辑所表达的观点是中肯的。如果收礼人偏爱别的礼物,而且这个礼物不比送礼人当前送的礼物贵,这就会造成资源不合理分配的情况。

长难句分析】

A gift will cause a misallocation of resources if the recipient would have preferred something else that would have been no more expensive for the donor to acquire.

[if !supportLists](1)[endif]【语法解析】

这句话是if引导的条件状语从句。 常见的条件状语从句的引导词是if和unless

你一定记得这句话:If winter comes, can spring be far behind?

本主句用将来时,叙说的是一个将来可能发生的事实。

(2)if the recipient would have preferred something else that would have been no more expensive for the donor to acquire.表示一种假设

翻译技巧】

增词与减词

增范畴词:如水平,方法,情况,方面,问题等。

王力《中国语法理论》中着重讲了“水平”,方式,方法,问题,情况,途径,方面 这七个词。

如何判断是否范畴词。汉语中出现这些词时,有两种方法,一是这些词出现在句末,词末,有可能是范畴词;二是和前面有大小关系。比如本段In strict monetary terms this is true.从严格的货币意义上来说,这种说法是正确的。增加了范畴词 “意义”。

更多笔记见公众号。

经济学人三期招新(8月15日到9月15日),还差几个名额,等你来上车!

QQ 群: