问题:

我们每天都要编写一些Python程序,或者用来处理一些文本,或者是做一些系统管理工作。程序写好后,只需要敲下python命令,便可将程序启动起来并开始执行:

$ python some-program.py

那么,一个文本形式的.py文件,是如何一步步转换为能够被CPU执行的机器指令的呢?此外,程序执行过程中可能会有.pyc文件生成,这些文件又有什么作用呢?

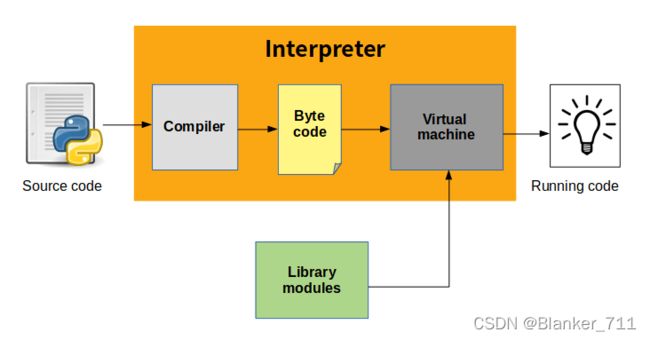

1. 执行过程

虽然从行为上看Python更像Shell脚本这样的解释性语言,但实际上Python程序执行原理本质上跟Java或者C#一样,都可以归纳为虚拟机和字节码。Python执行程序分为两步:先将程序代码编译成字节码,然后启动虚拟机执行字节码:

虽然Python命令也叫做Python解释器,但跟其他脚本语言解释器有本质区别。实际上,Python解释器包含编译器以及虚拟机两部分。当Python解释器启动后,主要执行以下两个步骤:

编译器将.py文件中的Python源码编译成字节码虚拟机逐行执行编译器生成的字节码

因此,.py文件中的Python语句并没有直接转换成机器指令,而是转换成Python字节码。

2. 字节码

Python程序的编译结果是字节码,里面有很多关于Python运行的相关内容。因此,不管是为了更深入理解Python虚拟机运行机制,还是为了调优Python程序运行效率,字节码都是关键内容。那么,Python字节码到底长啥样呢?我们如何才能获得一个Python程序的字节码呢——Python提供了一个内置函数compile用于即时编译源码。我们只需将待编译源码作为参数调用compile函数,即可获得源码的编译结果。

3. 源码编译

下面,我们通过compile函数来编译一个程序:

源码保存在demo.py文件中:

PI = 3.14

def circle_area(r):

return PI * r ** 2

class Person(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def say(self):

print('i am', self.name)

编译之前需要将源码从文件中读取出来:

>>> text = open('D:\myspace\code\pythonCode\mix\demo.py').read()

>>> print(text)

PI = 3.14

def circle_area(r):

return PI * r ** 2

class Person(object):

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def say(self):

print('i am', self.name)

然后调用compile函数来编译源码:

>>> result = compile(text,'D:\myspace\code\pythonCode\mix\demo.py', 'exec')

compile函数必填的参数有3个:

source:待编译源码

filename:源码所在文件名

mode:编译模式,exec表示将源码当作一个模块来编译

三种编译模式:

exec:用于编译模块源码

single:用于编译一个单独的Python语句(交互式下)

eval:用于编译一个eval表达式

4. PyCodeObject

通过compile函数,我们获得了最后的源码编译结果result:

>>> result

at 0x000001DEC2FCF680, file "D:\myspace\code\pythonCode\mix\demo.py", line 1>

>>> result.__class__

最终我们得到了一个code类型的对象,它对应的底层结构体是PyCodeObject

PyCodeObject源码如下:

/* Bytecode object */

struct PyCodeObject {

PyObject_HEAD

int co_argcount; /* #arguments, except *args */

int co_posonlyargcount; /* #positional only arguments */

int co_kwonlyargcount; /* #keyword only arguments */

int co_nlocals; /* #local variables */

int co_stacksize; /* #entries needed for evaluation stack */

int co_flags; /* CO_..., see below */

int co_firstlineno; /* first source line number */

PyObject *co_code; /* instruction opcodes */

PyObject *co_consts; /* list (constants used) */

PyObject *co_names; /* list of strings (names used) */

PyObject *co_varnames; /* tuple of strings (local variable names) */

PyObject *co_freevars; /* tuple of strings (free variable names) */

PyObject *co_cellvars; /* tuple of strings (cell variable names) */

/* The rest aren't used in either hash or comparisons, except for co_name,

used in both. This is done to preserve the name and line number

for tracebacks and debuggers; otherwise, constant de-duplication

would collapse identical functions/lambdas defined on different lines.

*/

Py_ssize_t *co_cell2arg; /* Maps cell vars which are arguments. */

PyObject *co_filename; /* unicode (where it was loaded from) */

PyObject *co_name; /* unicode (name, for reference) */

PyObject *co_linetable; /* string (encoding addr<->lineno mapping) See

Objects/lnotab_notes.txt for details. */

void *co_zombieframe; /* for optimization only (see frameobject.c) */

PyObject *co_weakreflist; /* to support weakrefs to code objects */

/* Scratch space for extra data relating to the code object.

Type is a void* to keep the format private in codeobject.c to force

people to go through the proper APIs. */

void *co_extra;

/* Per opcodes just-in-time cache

*

* To reduce cache size, we use indirect mapping from opcode index to

* cache object:

* cache = co_opcache[co_opcache_map[next_instr - first_instr] - 1]

*/

// co_opcache_map is indexed by (next_instr - first_instr).

// * 0 means there is no cache for this opcode.

// * n > 0 means there is cache in co_opcache[n-1].

unsigned char *co_opcache_map;

_PyOpcache *co_opcache;

int co_opcache_flag; // used to determine when create a cache.

unsigned char co_opcache_size; // length of co_opcache.

};

代码对象PyCodeObject用于存储编译结果,包括字节码以及代码涉及的常量、名字等等。关键字段包括:

| 字段 | 用途 |

|---|---|

| co_argcount | 参数个数 |

| co_kwonlyargcount | 关键字参数个数 |

| co_nlocals | 局部变量个数 |

| co_stacksize | 执行代码所需栈空间 |

| co_flags | 标识 |

| co_firstlineno | 代码块首行行号 |

| co_code | 指令操作码,即字节码 |

| co_consts | 常量列表 |

| co_names | 名字列表 |

| co_varnames | 局部变量名列表 |

下面打印看一下这些字段对应的数据:

通过co_code字段获得字节码:

>>> result.co_code b'd\x00Z\x00d\x01d\x02\x84\x00Z\x01G\x00d\x03d\x04\x84\x00d\x04e\x02\x83\x03Z\x03d\x05S\x00'

通过co_names字段获得代码对象涉及的所有名字:

>>> result.co_names

('PI', 'circle_area', 'object', 'Person')

通过co_consts字段获得代码对象涉及的所有常量:

>>> result.co_consts

(3.14, , 'circle_area', , 'Person', None)

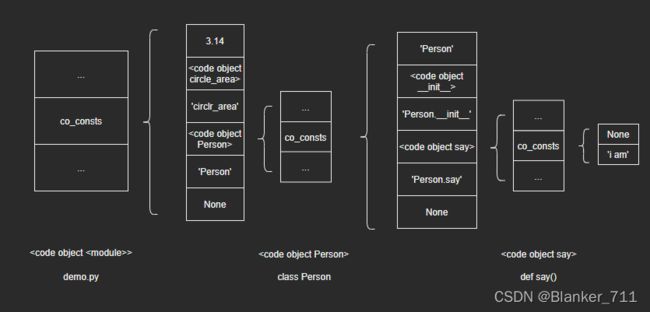

可以看到,常量列表中还有两个代码对象,其中一个是circle_area函数体,另一个是Person类定义体。对应Python中作用域的划分方式,可以自然联想到:每个作用域对应一个代码对象。如果这个假设成立,那么Person代码对象的常量列表中应该还包括两个代码对象:init函数体和say函数体。下面取出Person类代码对象来看一下:

>>> person_code = result.co_consts[3]

>>> person_code

>>> person_code.co_consts

('Person', , 'Person.__init__', , 'Person.say', None)

因此,我们得出结论:Python源码编译后,每个作用域都对应着一个代码对象,子作用域代码对象位于父作用域代码对象的常量列表里,层级一一对应。

至此,我们对Python源码的编译结果——代码对象PyCodeObject有了最基本的认识,后续会在虚拟机、函数机制、类机制中进一步学习。

5. 反编译

字节码是一串不可读的字节序列,跟二进制机器码一样。如果想读懂机器码,可以将其反汇编,那么字节码可以反编译吗?

通过dis模块可以将字节码反编译:

>>> import dis >>> dis.dis(result.co_code) 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (0) 2 STORE_NAME 0 (0) 4 LOAD_CONST 1 (1) 6 LOAD_CONST 2 (2) 8 MAKE_FUNCTION 0 10 STORE_NAME 1 (1) 12 LOAD_BUILD_CLASS 14 LOAD_CONST 3 (3) 16 LOAD_CONST 4 (4) 18 MAKE_FUNCTION 0 20 LOAD_CONST 4 (4) 22 LOAD_NAME 2 (2) 24 CALL_FUNCTION 3 26 STORE_NAME 3 (3) 28 LOAD_CONST 5 (5) 30 RETURN_VALUE

字节码反编译后的结果和汇编语言很类似。其中,第一列是字节码的偏移量,第二列是指令,第三列是操作数。以第一条字节码为例,LOAD_CONST指令将常量加载进栈,常量下标由操作数给出,而下标为0的常量是:

>>> result.co_consts[0]3.14

这样,第一条字节码的意义就明确了:将常量3.14加载到栈。

由于代码对象保存了字节码、常量、名字等上下文信息,因此直接对代码对象进行反编译可以得到更清晰的结果:

>>>dis.dis(result)

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (3.14)

2 STORE_NAME 0 (PI)

3 4 LOAD_CONST 1 ()

6 LOAD_CONST 2 ('circle_area')

8 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

10 STORE_NAME 1 (circle_area)

6 12 LOAD_BUILD_CLASS

14 LOAD_CONST 3 ()

16 LOAD_CONST 4 ('Person')

18 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

20 LOAD_CONST 4 ('Person')

22 LOAD_NAME 2 (object)

24 CALL_FUNCTION 3

26 STORE_NAME 3 (Person)

28 LOAD_CONST 5 (None)

30 RETURN_VALUE

Disassembly of :

4 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (PI)

2 LOAD_FAST 0 (r)

4 LOAD_CONST 1 (2)

6 BINARY_POWER

8 BINARY_MULTIPLY

10 RETURN_VALUE

Disassembly of :

6 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (__name__)

2 STORE_NAME 1 (__module__)

4 LOAD_CONST 0 ('Person')

6 STORE_NAME 2 (__qualname__)

7 8 LOAD_CONST 1 ()

10 LOAD_CONST 2 ('Person.__init__')

12 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

14 STORE_NAME 3 (__init__)

10 16 LOAD_CONST 3 ()

18 LOAD_CONST 4 ('Person.say')

20 MAKE_FUNCTION 0

22 STORE_NAME 4 (say)

24 LOAD_CONST 5 (None)

26 RETURN_VALUE

Disassembly of :

8 0 LOAD_FAST 1 (name)

2 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

4 STORE_ATTR 0 (name)

6 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

8 RETURN_VALUE

Disassembly of :

11 0 LOAD_GLOBAL 0 (print)

2 LOAD_CONST 1 ('i am')

4 LOAD_FAST 0 (self)

6 LOAD_ATTR 1 (name)

8 CALL_FUNCTION 2

10 POP_TOP

12 LOAD_CONST 0 (None)

14 RETURN_VALUE

操作数指定的常量或名字的实际值在旁边的括号内列出,此外,字节码以语句为单位进行了分组,中间以空行隔开,语句的行号在字节码前面给出。例如PI = 3.14这个语句就被会变成了两条字节码:

1 0 LOAD_CONST 0 (3.14)

2 STORE_NAME 0 (PI)

6. pyc

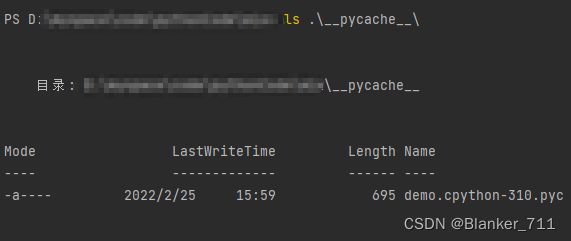

如果将demo作为模块导入,Python将在demo.py文件所在目录下生成.pyc文件:

>>> import demo

pyc文件会保存经过序列化处理的代码对象PyCodeObject。这样一来,Python后续导入demo模块时,直接读取pyc文件并反序列化即可得到代码对象,避免了重复编译导致的开销。只有demo.py有新修改(时间戳比.pyc文件新),Python才会重新编译。

因此,对比Java而言:Python中的.py文件可以类比Java中的.java文件,都是源码文件;而.pyc文件可以类比.class文件,都是编译结果。只不过Java程序需要先用编译器javac命令来编译,再用虚拟机java命令来执行;而Python解释器把这两个过程都完成了。

以上就是Python字节码与程序执行过程详解的详细内容,更多关于Python程序执行字节码的资料请关注脚本之家其它相关文章!