Working with Images in Google's Android

Working with Images in Google's Android

Google's Android platform really took the developers' world by storm with the announcement of the 10 million dollar challenges. Since its inception in late 2007, almost 1,800 new software entries had been submitted from all over the world and some of them already made the technical news headlines because of their innovative ideas. A few interesting concepts have been introduced in this platform although, at the beginning, some developers thought it could be nothing but a combination of Linux and Java along with Google's own APIs. By way of focusing on image-related work, this article should give you an idea how easy it is to work with Android and how powerful this platform is.

What Do You Need to Start?

At the moment, there are very few references available about Android. The best source is from Google's own Android site at http://code.google.com/android/. It has all the necessary development tools, plug-ins, and sample codes you need to download. Simply follow the step-by-step instructions to get them all. It surely does not make much sense for me to repeat here. In addition to the online documentation, you can look for technical help by participating in the community forums. If you are a complete novice about Android, I would recommend you choose the free development tool Eclipse because it integrates better with Android SDK as well as the debugging software and emulators. There are other ways of building projects through command-line or batch scripts, but using Eclipse should be the easiest way to start, according to many fellow developers' experience.

What APIs Are Available for Processing Images?

- Post a comment

- Email Article

- Print Article

Android's APIs cover lots of great features, including:

- SQLite for structured data storage: You can embed a tiny database with your application without much effort.

- Graphics library support: Optimized 2D graphics library and 3D graphics based on the embedded version of OpenGL ES.

- Integrated web browser support

- Media support: This supports common audio, video, and still-image formats.

- Google APIs: Mapping capability allows third-party code to display and control a Google Map. It also supports P2P services via XMPP called GTalkService.

- Hardware-dependent support: There are many expected APIs for GSM Telephony, Bluetooth, EDGE, 3G, WiFi, camera, Location-Based Services (via GPS and so forth), compass, and accelerometer.

Out of the large collection of APIs, you'll mainly look at those under these two packages extracted from the online description:

- android.graphics: This provides low-level graphics tools such as canvases, color filters, points, and rectangles that let you handle drawing to the screen directly.

- android.graphics.drawable: This provides classes to manage a variety of visual elements that are intended for display only, such as bitmaps and gradients.

Images are bitmaps, so you'll rely heavily on the APIs under android.graphics.Bitmap.

File I/O and Supported Image Formats

Android supports several common still-image formats such as PNG, JPG, and GIF. In the example, you will use the JPG format. If you consider using the transparency feature for the image, the PNG format would be a better choice.

To read an image file that is packaged with your software, you should put it under the res/drawable folder relative to your software's root. Once the image is in the folder, a resource ID will be generated automatically when you re-compile the package. For example, you have the image file called pic1.jpg. It will become accessible programmatically through its resource ID R.drawable.pic1. You can see that the image file extension has been stripped off and the upper case R represents the overall resource file, R.java. R.java is generated automatically and should not be edited unless you have a pretty good understanding of how resources are structured in this file. Here is the code segment showing how you can refer to an image through its resource ID.

Bitmap mBitmap = BitmapFactory.decodeResource(getResources(), R.drawable.pic1); int pic_width = mBitmap.width(); int pic_height = mBitmap.height();

To read or write an image file without specifying the folder structure, it will be under /data/data/YourPackageName/files/ on the emulator. For example, you will create your package name for your example as package com.cyl.TutorialOnImages. Therefore, if you create a new image file at runtime, it will be under the /data/data/com.cyl.TutorialOnImages/files/ folder. Please note that each Android application will start with its own user and group ID, so some file folders are not accessible through your software unless they are specifically set to do so. Here is the code for when you want to output a bitmap onto a file called output.jpg.

try {

FileOutputStream fos = super.openFileOutput("output.jpg",

MODE_WORLD_READABLE);

mBitmap.compress(CompressFormat.JPEG, 75, fos);

fos.flush();

fos.close();

} catch (Exception e) {

Log.e("MyLog", e.toString());

}

Image View, Colors, and Transparency

Each Android application should have a screen layout. It can be created dynamically inside the software, or it can be specified through an external XML file. The default is main.xml. To contain an image, you use a View class called ImageView. Here is what the content of the main.xml file looks like:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <LinearLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/ apk/res/android" android:orientation="vertical" android:layout_width="fill_parent" android:layout_height="fill_parent" > <ImageView id="@+id/picview" android:layout_width="wrap_content" android:layout_height="wrap_content" /> </LinearLayout>

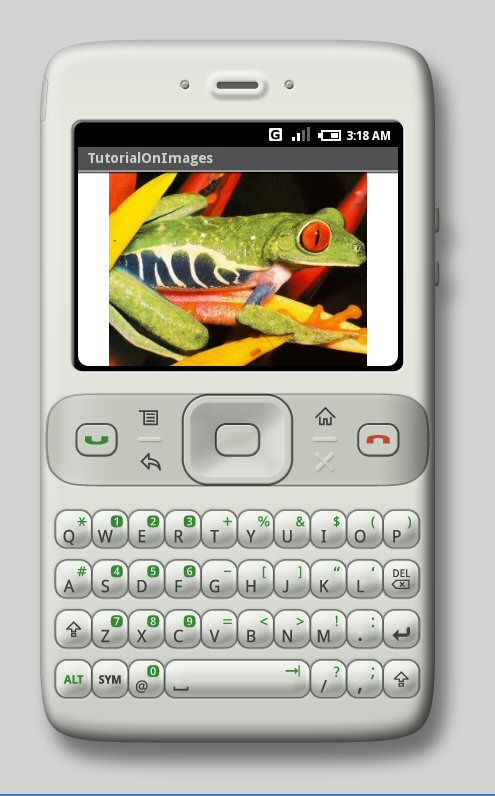

Just as the image file can be accessed through a resource ID, main.xml will have a resource ID called R.layout.main automatically generated in the global resource file R.java after compilation. Here is the initial view when the application first starts on the emulator.

Click here for a larger image.

Figure 1: Software first starts on the emulator

Each image pixel is represented as a 4-byte integer. The highest byte is for the alpha channel; in other words, the opacity/transparency control. A value 255 means the pixel is completely opaque; 0 means it is entirely transparent. The next byte is for the red channel; 255 represents a fully saturated red. Similarly, the next two bytes are for the green and blue channels respectively.

Manipulating Image Pixels

- Post a comment

- Email Article

- Print Article

Now, you can proceed to work on individual pixels. getPixels in the android.graphics.Bitmap API is used to load the pixels into an integer array. In this example, you are tinting each image pixel by an angle in degrees. After the process, all pixels are made sure to fall within the byte range from 0 to 255. setPixels in the android.graphics.Bitmap API is used to load the integer array onto an image. The last step is to update the screen through the ImageView variable mIV. Here is the code segment for performing the tinting process.

private void TintThePicture(int deg) {

int[] pix = new int[picw * pich];

mBitmap.getPixels(pix, 0, picw, 0, 0, picw, pich);

int RY, GY, BY, RYY, GYY, BYY, R, G, B, Y;

double angle = (3.14159d * (double)deg) / 180.0d;

int S = (int)(256.0d * Math.sin(angle));

int C = (int)(256.0d * Math.cos(angle));

for (int y = 0; y < pich; y++)

for (int x = 0; x < picw; x++)

{

int index = y * picw + x;

int r = (pix[index] >> 16) & 0xff;

int g = (pix[index] >> 8) & 0xff;

int b = pix[index] & 0xff;

RY = ( 70 * r - 59 * g - 11 * b) / 100;

GY = (-30 * r + 41 * g - 11 * b) / 100;

BY = (-30 * r - 59 * g + 89 * b) / 100;

Y = ( 30 * r + 59 * g + 11 * b) / 100;

RYY = (S * BY + C * RY) / 256;

BYY = (C * BY - S * RY) / 256;

GYY = (-51 * RYY - 19 * BYY) / 100;

R = Y + RYY;

R = (R < 0) ? 0 : ((R > 255) ? 255 : R);

G = Y + GYY;

G = (G < 0) ? 0 : ((G > 255) ? 255 : G);

B = Y + BYY;

B = (B < 0) ? 0 : ((B > 255) ? 255 : B);

pix[index] = 0xff000000 | (R << 16) | (G << 8) | B;

}

Bitmap bm = Bitmap.createBitmap(picw, pich, false);

bm.setPixels(pix, 0, picw, 0, 0, picw, pich);

// Put the updated bitmap into the main view

mIV.setImageBitmap(bm);

mIV.invalidate();

mBitmap = bm;

pix = null;

}

Figure 2: Result after hitting the middle button

Putting All the Pieces Together

From having read previous sections, you know how to import and export an image file, create a view for it, and process each pixel in the image. One thing you want to add is to provide a simple user interaction so that a sequence of events can happen in response to the user's input. The APIs in android.view.KeyEvent allow you to handle the key presses. The software is set to wait for the key press event of the direction pad's center key. When it is pressed, it will tint the picture by an angle of 20 degrees and save the result into a file.

public boolean onKeyDown(int keyCode, KeyEvent event) {

if (keyCode == KeyEvent.KEYCODE_DPAD_CENTER) {

// Perform the tinting operation

TintThePicture(20);

// Display a short message on screen

nm.notifyWithText(56789, "Picture was tinted",

NotificationManager.LENGTH_SHORT, null);

// Save the result

SaveThePicture();

return (true);

}

return super.onKeyDown(keyCode, event);

}

Some Advice Before Moving In

- If it takes too long to process all the image pixels (approximately five seconds), you could get a popup dialog called Application Not Responding, or ANR. You should create a child thread, and do the complicated calculation there. That should keep the main thread running without interruption.

- If the child thread needs to change the main view (for example, update the image), you should use a message handler in the main thread to listen for the notification from the child thread and then update the view accordingly. A child thread cannot modify the view in the main thread directly.

- Some enhancements can be made. For example, it can be modified to read the image file from browsing the folders or from a URL. Image animation can be done carefully through multi-threading and message handling along with rectangle clipping to produce smooth transition effects.

Conclusion

Hopefully, the information provided here has given you a rough idea how Android works. I hope you come up with your own application for the challenge as well.

References

- Download and save the entire software project

- Android: An Open Handset Alliance Project at http://code.google.com/android/

- Android Development Community at http://www.anddev.org

- Androidlet at http://www.androidlet.com

- Rafael C. Gonzalez and Richard E. Woods, Digital Image Processing, Addison-Wesley Publishing, 1994

About the Author

- Post a comment

- Email Article

- Print Article

Chunyen Liu has been with the engineering department at a world's leading GPS company for a while. Some of his applications were among winners at programming contests administered by SUN, ACM, and IBM. He also had co-authored U.S. patents and written articles for various publishers. He holds advanced degrees in computer science and operates a hobby site called The J Maker. On the non-technical side, he is a tournament-rated table tennis player, certified umpire, and certified coach of USA Table Tennis.