gamma correction

UNDERSTANDING GAMMA CORRECTION

Gamma is an important but seldom understood characteristic of virtually all digital imaging systems. It defines the relationship between a pixel's numerical value and its actual luminance. Without gamma, shades captured by digital cameras wouldn't appear as they did to our eyes (on a standard monitor). It's also referred to as gamma correction, gamma encoding or gamma compression, but these all refer to a similar concept. Understanding how gamma works can improve one's exposure technique, in addition to helping one make the most of image editing.

WHY GAMMA IS USEFUL

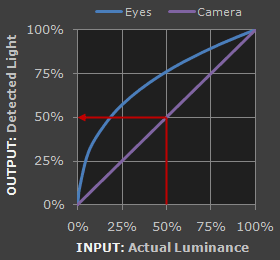

1. Our eyes do not perceive light the way cameras do. With a digital camera, when twice the number of photons hit the sensor, it receives twice the signal (a "linear" relationship). Pretty logical, right? That's not how our eyes work. Instead, we perceive twice the light as being only a fraction brighter — and increasingly so for higher light intensities (a "nonlinear" relationship).

|

|

|

| Reference Tone | ||

|

||

| Perceived as 50% as Bright by Our Eyes |

||

| Detected as 50% as Bright by the Camera |

Refer to the tutorial on the photoshop curves tool if you're having trouble interpreting the graph.

Accuracy of comparison depends on having a well-calibrated monitor set to a display gamma of 2.2.

Actual perception will depend on viewing conditions, and may be affected by other nearby tones.

For extremely dim scenes, such as under starlight, our eyes begin to see linearly like cameras do.

Compared to a camera, we are much more sensitive to changes in dark tones than we are to similar changes in bright tones. There's a biological reason for this peculiarity: it enables our vision to operate over a broader range of luminance. Otherwise the typical range in brightness we encounter outdoors would be too overwhelming.

But how does all of this relate to gamma? In this case, gamma is what translates between our eye's light sensitivity and that of the camera. When a digital image is saved, it's therefore "gamma encoded" — so that twice the value in a file more closely corresponds to what we would perceive as being twice as bright.

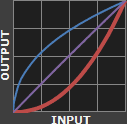

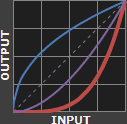

Technical Note: Gamma is defined by Vout = Vingamma , where Vout is the output luminance value and Vin is the input/actual luminance value. This formula causes the blue line above to curve. When gamma<1, the line arches upward, whereas the opposite occurs with gamma>1.

2. Gamma encoded images store tones more efficiently. Since gamma encoding redistributes tonal levels closer to how our eyes perceive them, fewer bits are needed to describe a given tonal range. Otherwise, an excess of bits would be devoted to describe the brighter tones (where the camera is relatively more sensitive), and a shortage of bits would be left to describe the darker tones (where the camera is relatively less sensitive):

| Original: | |

| ↓ Encoded using only 32 levels (5 bits) |

|

| Linear Encoding: |

|

| Gamma Encoding: |

|

Note: Above gamma encoded gradient shown using a standard value of 1/2.2

See the tutorial on bit depth for a background on the relationship between levels and bits.

Notice how the linear encoding uses insufficient levels to describe the dark tones — even though this leads to an excess of levels to describe the bright tones. On the other hand, the gamma encoded gradient distributes the tones roughly evenly across the entire range ("perceptually uniform"). This also ensures that subsequent image editing, color andhistograms are all based on natural, perceptually uniform tones.

However, real-world images typically have at least 256 levels (8 bits), which is enough to make tones appear smooth and continuous in a print. If linear encoding were used instead, 8X as many levels (11 bits) would've been required to avoid image posterization.

GAMMA WORKFLOW: ENCODING & CORRECTION

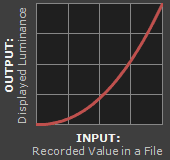

Despite all of these benefits, gamma encoding adds a layer of complexity to the whole process of recording and displaying images. The next step is where most people get confused, so take this part slowly. A gamma encoded image has to have "gamma correction" applied when it is viewed — which effectively converts it back into light from the original scene. In other words, the purpose of gamma encoding is for recording the image — not for displaying the image. Fortunately this second step (the "display gamma") is automatically performed by your monitor and video card. The following diagram illustrates how all of this fits together:

| RAW Camera Image is Saved as a JPEG File | JPEG is Viewed on a Computer Monitor | Net Effect | ||

|

+ |  |

= |  |

| 1. Image File Gamma | 2. Display Gamma | 3. System Gamma |

1. Depicts an image in the sRGB color space (which encodes using a gamma of approx. 1/2.2).

2. Depicts a display gamma equal to the standard of 2.2

1. Image Gamma. This is applied either by your camera or RAW development software whenever a captured image is converted into a standard JPEG or TIFF file. It redistributes native camera tonal levels into ones which are more perceptually uniform, thereby making the most efficient use of a given bit depth.

2. Display Gamma. This refers to the net influence of your video card and display device, so it may in fact be comprised of several gammas. The main purpose of the display gamma is to compensate for a file's gamma — thereby ensuring that the image isn't unrealistically brightened when displayed on your screen. A higher display gamma results in a darker image with greater contrast.

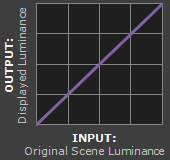

3. System Gamma. This represents the net effect of all gamma values that have been applied to an image, and is also referred to as the "viewing gamma." For faithful reproduction of a scene, this should ideally be close to a straight line (gamma = 1.0). A straight line ensures that the input (the original scene) is the same as the output (the light displayed on your screen or in a print). However, the system gamma is sometimes set slightly greater than 1.0 in order to improve contrast. This can help compensate for limitations due to the dynamic range of a display device, or due to non-ideal viewing conditions and image flare.

IMAGE FILE GAMMA

The precise image gamma is usually specified by a color profile that is embedded within the file. Most image files use an encoding gamma of 1/2.2 (such as those using sRGB and Adobe RGB 1998 color), but the big exception is with RAW files, which use a linear gamma. However, RAW image viewers typically show these presuming a standard encoding gamma of 1/2.2, since they would otherwise appear too dark:

If no color profile is embedded, then a standard gamma of 1/2.2 is usually assumed. Files without an embedded color profile typically include many PNG and GIF files, in addition to some JPEG images that were created using a "save for the web" setting.

Technical Note on Camera Gamma. Most digital cameras record light linearly, so their gamma is assumed to be 1.0, but near the extreme shadows and highlights this may not hold true. In that case, the file gamma may represent a combination of the encoding gamma and the camera's gamma. However, the camera's gamma is usually negligible by comparison. Camera manufacturers might also apply subtle tonal curves, which can also impact a file's gamma.

DISPLAY GAMMA

This is the gamma that you are controlling when you perform monitor calibration and adjust your contrast setting. Fortunately, the industry has converged on a standard display gamma of 2.2, so one doesn't need to worry about the pros/cons of different values. Older macintosh computers used a display gamma of 1.8, which made non-mac images appear brighter relative to a typical PC, but this is no longer the case.

Recall that the display gamma compensates for the image file's gamma, and that the net result of this compensation is the system/overall gamma. For a standard gamma encoded image file (—), changing the display gamma (—) will therefore have the following overall impact (—) on an image:

Diagrams assume that your display has been calibrated to a standard gamma of 2.2.

Recall from before that the image file gamma (—) plus the display gamma (—) equals the overall system gamma (—). Also note how higher gamma values cause the red curve to bend downward.

If you're having trouble following the above charts, don't despair! It's a good idea to first have an understanding of how tonal curves impact image brightness and contrast. Otherwise you can just look at the portrait images for a qualitative understanding.

How to interpret the charts. The first picture (far left) gets brightened substantially because the image gamma (—) is uncorrected by the display gamma (—), resulting in an overall system gamma (—) that curves upward. In the second picture, the display gamma doesn't fully correct for the image file gamma, resulting in an overall system gamma that still curves upward a little (and therefore still brightens the image slightly). In the third picture, the display gamma exactly corrects the image gamma, resulting in an overall linear system gamma. Finally, in the fourth picture the display gamma over-compensates for the image gamma, resulting in an overall system gamma that curves downward (thereby darkening the image).

The overall display gamma is actually comprised of (i) the native monitor/LCD gamma and (ii) any gamma corrections applied within the display itself or by the video card. However, the effect of each is highly dependent on the type of display device.

CRT Monitors. Due to an odd bit of engineering luck, the native gamma of a CRT is 2.5 — almost the inverse of our eyes. Values from a gamma-encoded file could therefore be sent straight to the screen and they would automatically be corrected and appear nearly OK. However, a small gamma correction of ~1/1.1 needs to be applied to achieve an overall display gamma of 2.2. This is usually already set by the manufacturer's default settings, but can also be set during monitor calibration.

LCD Monitors. LCD monitors weren't so fortunate; ensuring an overall display gamma of 2.2 often requires substantial corrections, and they are also much less consistent than CRT's. LCDs therefore require something called a look-up table (LUT) in order to ensure that input values are depicted using the intended display gamma (amongst other things). See the tutorial on monitor calibration: look-up tables for more on this topic.

Technical Note: The display gamma can be a little confusing because this term is often used interchangeably with gamma correction, since it corrects for the file gamma. However, the values given for each are not always equivalent. Gamma correction is sometimes specified in terms of the encoding gamma that it aims to compensate for — not the actual gamma that is applied. For example, the actual gamma applied with a "gamma correction of 1.5" is often equal to 1/1.5, since a gamma of 1/1.5 cancels a gamma of 1.5 (1.5 * 1/1.5 = 1.0). A higher gamma correction value might therefore brighten the image (the opposite of a higher display gamma).

OTHER NOTES & FURTHER READING

Other important points and clarifications are listed below.

- Dynamic Range. In addition to ensuring the efficient use of image data, gamma encoding also actually increases the recordable dynamic range for a given bit depth. Gamma can sometimes also help a display/printer manage its limited dynamic range (compared to the original scene) by improving image contrast.

- Gamma Correction. The term "gamma correction" is really just a catch-all phrase for when gamma is applied to offset some other earlier gamma. One should therefore probably avoid using this term if the specific gamma type can be referred to instead.

- Gamma Compression & Expansion. These terms refer to situations where the gamma being applied is less than or greater than one, respectively. A file gamma could therefore be considered gamma compression, whereas a display gamma could be considered gamma expansion.

- Applicability. Strictly speaking, gamma refers to a tonal curve which follows a simple power law (where Vout = Vingamma), but it's often used to describe other tonal curves. For example, the sRGB color space is actually linear at very low luminosity, but then follows a curve at higher luminosity values. Neither the curve nor the linear region follow a standard gamma power law, but the overall gamma is approximated as 2.2.

- Is Gamma Required? No, linear gamma (RAW) images would still appear as our eyes saw them — but only if these images were shown on a linear gamma display. However, this would negate gamma's ability to efficiently record tonal levels.

For more on this topic, also visit the following tutorials:

- Digital Exposure Techniques: Expose to the Right, Clipping & Noise

Learn why gamma and linear RAW files influence a photo's optimal exposure. - How to Calibrate Your Monitor Calibration for Photography

Learn how to accurately set your computer's display gamma.

Gamma 校正

问题:什么是Gamma曲线矫正?Gamma曲线矫正是什么意思?

Gamma曲线是一种特殊的色调曲线,当Gamma值等于1的时候,曲线为与坐标轴成45°的直线,这个时候表示输入和输出密度相同。高于1的Gamma值将会造成输出亮化,低于1的Gamma值将会造成输出暗化。总之,我们的要求是输入和输出比率尽可能地接近于1。在显示器、扫描仪、打印机等输入、输出设备中这是一个相当常见并且比较重要的概念。在计算机系统中,由于显卡或者显示器的原因会出现实际输出的图像在亮度上有偏差,而Gamma曲线矫正就是通过一定的方法来矫正图像的这种偏差的方法。一般情况下,当用于Gamma矫正的值大于1时,图像的高光部分被压缩而暗调部分被扩展,当Gamma矫正的值小于1时,图像的高光部分被扩展而暗调部分被压缩,Gamma矫正一般用于平滑的扩展暗调的细节。

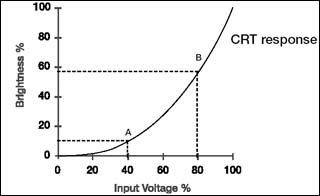

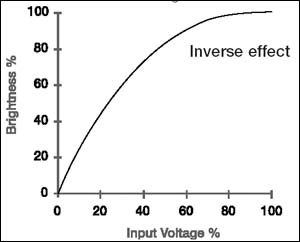

图1显示的是一般CRT显示器的亮度响应曲线,可以看到其输入电压提高一倍,亮度输出并不是提高一倍,而是接近于两倍,显然这样输出的图像同原来的图像相比就发生了输出亮化的现象,也就是说未经过Gamma矫正的CRT显示器其Gamma值是小于1的。

没有经过Gamma矫正的设备会影响最终输出图像的颜色亮度,比如一种颜色由红色和绿色组成,红色的亮度为50%,绿色的亮度为25%,如果一个未经过Gamma矫正的CRT显示器的Gamma值是2.5,那么输出结果的亮度将分别为18%和3%,其亮度大大的降低了。

图2 按图进行曲线补偿

图2 按图进行曲线补偿

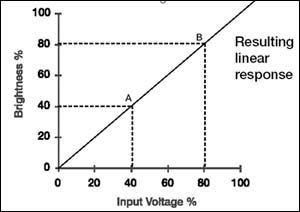

为了补偿这方面的不足,我们需要使用反效果补偿曲线来让显示器尽可能地输出同输入图像相同的图像,所以这个时候显示器的输入信号应该按照图2所示的曲线进行补偿,这样才能在显示器上得到比较理想的输出结果。

一般的反效果可以直接被赋予存储在帧缓存中的图像,使之Gamma曲线呈非线性,也可以通过RAMDAC进行这种反效果补偿(或者说是Gamma曲线矫正)。这样我们就可以在显示器上看到同我们输入的图像接近的图像了(如图3)。当然图3所示的曲线只是理想状态下的情况,在实际应用中我们并不可能得到如此完美的曲线,所以不同的厂商之间所竞争的就是谁能做到最接近于这个效果。

显示器的gamma值是用于定义一个显示器的显示特性的数学方法,是决定显示器从黑色到白色的值。简单的说,当显示一个颜色从黑到白时(也就是0到1),显示器的电压也要随之变化,但这个变化不是线性的。因为显示器的物理特性决定了如果电压的变化是线性的,显示出来的亮度就不是线性的,这时,显示的亮度就会很暗。所以,为了保整显示出来的亮度是正常(线性)的,就需要对显示器的电压变化加以校正,这个值就是我们通常所说的gamma值。通常情况只有在调整HDRI图片时和在做动画渲染时会用到。

原文:http://macx.cn/MINI/Default.asp?600-710444-0-0-0-0-0-a-.htm

γ校正(Gamma Correction,伽玛校正):所 谓伽玛校正就是对图像的伽玛曲线进行编辑,以对图像进行非线性色调编辑的方法,检出图像信号中的深色部分和浅色部分,并使两者比例增大,从而提高图像对比 度效果。计算机绘图领域惯以此屏幕输出电压与对应亮度的转换关系曲线,称为伽玛曲线(Gamma Curve)。以传统CRT(Cathode Ray Tube)屏幕的特性而言,该曲线通常是一个乘幂函数,Y=(X+e)γ,其中,Y为亮度、X为输出电压、e为补偿系数、乘幂值(γ)为伽玛值,改变乘幂 值(γ)的大小,就能改变CRT的伽玛曲线。典型的Gamma值是0.45,它会使CRT的影像亮度呈现线性。使用CRT的电视机等显示器屏幕,由于对于 输入信号的发光灰度,不是线性函数,而是指数函数,因此必需校正。

在电视和图形监视器中,显像管发生的电子束及其生成的图像亮度并不是随显像管的输入电压线性变化,电子流与输入电压相比是按照指数曲线变化的,输入 电压的指数要大于电子束的指数。这说明暗区的信号要比实际情况更暗,而亮区要比实际情况更高。所以,要重现摄像机拍摄的画面,电视和监视器必须进行伽玛补 偿。这种伽玛校正也可以由摄像机完成。我们对整个电视系统进行伽玛补偿的目的,是使摄像机根据入射光亮度与显像管的亮度对称而产生的输出信号,所以应对图 像信号引入一个相反的非线性失真,即与电视系统的伽玛曲线对应的摄像机伽玛曲线,它的值应为1/γ,我们称为摄像机的伽玛值。电视系统的伽玛值约为 2.2,所以电视系统的摄像机非线性补偿伽玛值为0.45。彩色显像管的伽玛值为2.8,它的图像信号校正指数应为1/2.8=0.35,但由于显像管内 外杂散光的影响,重现图像的对比度和饱和度均有所降低,所以现在的彩色摄像机的伽玛值仍多采用0.45。在实际应用中,我们可以根据实际情况在一定范围内 调整伽玛值,以获得最佳效果。

原文:http://www.52rd.com/blog/Detail_RD.Blog_lifeboy262_16204.html

今天有个朋友问γ校正的用处,这里简单说一下

伽马校正最初是由于显示器的阴极现象管(也就是物理上所说的示波管的阴极射线版)的成像扭曲引起的,为了不使画面失真所以就用先特殊算法进行校正,此之谓γ校正。

γ校正的原理是修改显示系统的配色方案,本来显示系统输出的r g b电子枪线性的根据显存中的各个颜色值输出对应的控制电压,但是通过伽码校正可以把某个颜色值对应的输出电压调整高或调整低。达到校正显示系统色泽的目的。

同时可以用软件的方法校正,就是对一副图片设定某个颜色的颜色值变换成新的颜色值的对照表,然后用新的颜色值取代原来图片中对应的颜色就行了呀。比如你先编写一个控制rgb各个分量对应关系的曲线调节器,在曲线调节器里面调整控制曲线设置原来颜色多少对应目标颜色多少,然后根据设定的关系,修改要调整色泽的图片每一个像素的颜色就可以了。

在一些游戏里面有Gamma校正这一个选项,关系到画面的亮度问题,如果画面太暗可以适当调高。

原文:http://hi.baidu.com/eiloxcn/blog/item/3d28b00f6809482c6159f338.html

数学公式可以深刻和精确的把握一个概念,却不能表达概念的物理意义和本质含义,本贴试图摆脱数学公式的陈述和推导,用言语来解释gamma的本质含义。

1什么是gamma?

对于CRT显示器,输入电压信号将在屏幕上产生亮度输出,但是显示器的亮度与输入的电压信号不成正比,存在一种失真,如果输入的是黑白图像信号,这种失真将使被显示的图像的中间调偏暗,从而使图像的整体比原始场景偏暗,如果输入的是彩色图像信号,这种失真除了使显示的图像偏暗以外,还会使显示的图像的色调发生偏移。gamma就是这种失真的度量参数。对于CRT显示器,无论什么品牌的,由于其物理原理的一致性,其gamma值几乎是一个常量,为2.5。(注意,gamma=1.0时不存在失真),由于存在gamma失真,输入电压信号所代表的图像,在屏幕上显示时比原始图像暗。如下图所示。

原始图像电压信号

屏幕输出图像(失真)

2 gamma概念的演化

gamma本来是显示器的输出图像对输入信号失真的度量参数。

2.1 gamma概念的第一演化(系统gamma和显示器gamma)

由于存在显示失真,这样的图像不能应用,所以需要校正这种失真。上文讲到,对于显示器来说,gamma值是常量,不可改变,所以校正过程就只能针对输入的图像电压信号了。这种校正就是将正常的图像电压信号向显示器失真的相反方向去调整,既然失真使图像的中间调变暗,那么在图像电压信号输入到显示器之前,先将该电压信号的中间调调亮,然后再输入到显示器,这样就可以抵消显示器的失真了,如图所示。

原始图像电压信号

校正后的图像电压信号

屏幕输出图像(不失真)

由于显示器的gamma值是常量,所以这种校正的幅度也是相对固定的,这种校正幅度的度量参数也叫gamma,这是gamma概念的第一次演化,为了区别这两种不同的概念,此处的gamma又叫做系统gamma(因为对图像电压信号的校正过程发生在电脑系统中),显示器的固有的gamma又叫做显示器gamma。

2.2 gamma概念的第二次演化

显示器gamma表示一种失真,系统gamma表示一种校正,这两者共同之处是都表示对原始信号的一种变换,所以gamma概念发展到这里,其一般性含义已经又两层含义,a表示对原始信号的一种变换, b表示这种变换的度量参数。

2.3 gamma概念的第三次演化(文件gamma)

既然gamma的一般性含义是对原始信号的一种变换,可想而知,文件gamma也一定表示一种变换,这是一种什么样的变换呢?

从宏观上讲,被照相机拍摄的物体的亮度是连续变化的,如果将亮度连续变化的被摄物体的图像转换成数字文件(计算机文件)时,无论用数码相机还是扫描仪,都要面临用离散的数值去近似表示连续的物理量的问题。具体来说,一个8位的二进制数字文件,如何编码才能比较精确的表示反差很大的一幅图像?

这要从人的视觉原理说起。人的眼睛感觉到亮度增加一级的时候,光强(光的能量)将增加一倍,同样,当人的眼睛感觉到亮度减小一级的时候,光强将减少一半。就是说,人的眼睛感觉到的亮度的成比例的线性变化,是由光强的倍数变化引起的。如果将一段连续变化的亮度从暗到亮等差分成a b c d e f g 七段,那么这七段亮度对应的光强不是1 2 3 4 5 6 7,而是1 2 4 8 16 32 64。打个数学比方,人眼感觉到的亮度是等差数列,而光强的物理实在是等比数列!为何如此,因为这样可以确保人眼即适应高亮度的阳光下的景物,又能在夜晚看清星光下的猎物,这是大自然的造化。

数码相机或扫描仪的感光元件,将会把光强变成电信号,然后由模-数转换器件转换成数字信号,继而再存储为数字文件。为了便于讨论,以黑白图像为例,一个黑白图片数字文件中每个象素用一个8位二进制编码表示,8位二进制编码只有256个量级,从0到255。就是说,一幅图片,最亮的地方用255表示,最暗的地方用0表示。这里有一个问题需要我们思考一下:比最亮处(编码255)暗一级的象素的编码值是多少?

答案是128,因为人眼感觉暗一级,光强将减小一半,这样感光元件的输出电压值将减小一半,从而模-数转换器件得到的数字值也是255的一半,即128。

依此类推,比最亮的象素(编码255)暗两级的象素的编码值是64,暗三级是32,暗四级是16,暗五级是8,暗六级是4,暗七级是2,暗八级是1。于是矛盾就出现了:

第一问题是,亚当斯将曝光区分为11个等级,这种8位二进制编码方法无法表示11个分区,只表示了9个分区,分别对应的二进制编码值是0-1,1-2,2-4,4-8,8-16,16-32,32-64,64-128,128-255。

更严重的是第二个问题,最亮的分区(128-255)占有8位二进制编码256个量级的一半量级资源,即占有128个量级,分别是128,129,130,……,253,254,255。而最暗的分区只占有8位二进制编码256个量级中的两个量级,分别是0和1,比最亮分区暗四级的分区只占有8位二进制编码256个量级中的8个量级,分别是8,9,……,15,16。这表明这种编码方法在最亮的分区中,表达的亮度细节非常的丰富,超过人眼的识别能力(人眼在亮处可以识别1%的亮度变化),可是在较暗的分区中,表达的亮度细节就少的可怜了,会出现马赛克!

所以需要对感光元件的输出的电压值在模-数转换时做一种变换,使得较暗的分区占有的二进制编码量级多一些,较亮的分区占有的二进制编码量级少一些,从而不至于使图像暗处出现马赛克,也使亮部占有的量级刚好满足人眼的最大识别能力。这样编码的数字文件可以较好的表示反差很大的一幅图像。文件gamma是表示这种变换的度量参数。Windows系统,WWW和sRGB规定文件gamma值为2.2。

2.4 gamma概念的第四次演化

a表示对原始信号的一种变换,泛指显示器gamma,系统gamma,文件gamma。

b表示这种变换的度量参数。

c 在不同的上下文环境中,会特指显示器gamma,系统gamma,文件gamma三个概念中的某个具体概念,注意领会。

2.5 概念总结(四种gamma)

2.5.1 gamma

gamma在不同的上下文环境中,有不同的含义,一个意思是表示对原始信号的一种变换,另一个意思是表示这种变换的度量参数,还可能表示显示器gamma,系统gamma,文件gamma三个概念中的某个具体概念。

2.5.2 显示器gamma

是显示器的物理属性,固定的,不变的,不可校正的。显示器gamma在不同的上下文环境中,有不同的含义,一个意思是指显示器的输出图像对输入信号的失真,另一个意思是指这种失真的具体数值。

2.5.3 文件gamma

对一个给定的数码相片文件,按照相关标准规范, 这个gamma是一个定值,所以无需对其校正。如果出于某种特殊需要,一定要改变某数码相片文件的gamma值,这种改变也不能称作“校正”,而是称作“变换”。

2.5.4 系统gamma

系统gamma所表示的变换,是计算机系统在读取了照片数字文件之后,在输出到显示器之前的一种变换,对于windows系统它存在于显卡中,是可调节的,可校正的。

3在使用计算机处理数码相片时总要提到gamma校正,这里的gamma校正过程校正什么?

由于显示器gamma和文件gamma是固定不变的,gamma校正过程是校正计算机的系统gamma!,使得显示器gamma、系统gamma、文件gamma三个变换的叠加为1.0,从而使最终显示器的图像和原始场景一样,不存在失真。

这就好比密码通信,文件gamma是加密过程,系统gamma和显示器gamma是文件gamma的一种反作用,是解密过程,最后看到的结果和原始信息一样。

原文:http://bbs.photoshopcn.com/viewthread.php?tid=376356

还有篇文章不错,要看的话搜索 Gamma校正的快速算法及其C语言实现

这里简单说下他的算法,我也不知道为什么要弄个

如一个像素(r,g,b)

以r来说 先归一化,转到[0,1]

temp = (r+0.5)/256

预补偿公式temp = temp ^(1/gamma) 其中gamma一般是2.2

最后转化回RGB

r = temp*256 – 0.5

这里计算比较耗损,可以先建立一个映射表(数组),然后查表来做

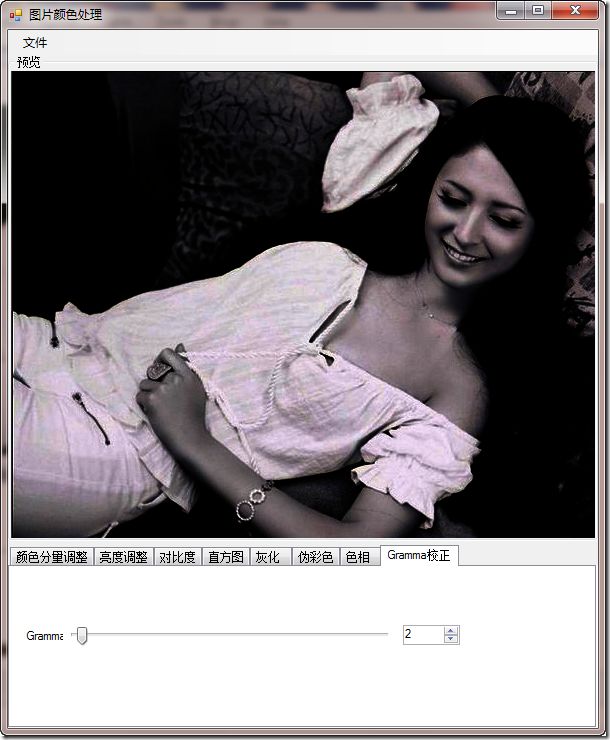

原图很明显太亮衣服纹理不清晰

处理后衣服条文清晰,当然这是为了太亮而设置的,实际上很多时候是太黑设置。

这里的数目我偷懒了,本来gamma的取值范围应该是[0.1,5]的。

而且我算法,最亮也没有采取255而是,从图像中用加权平均值拿了最大的,因为我认为这个主要是为了处理图像的中间过渡色的,平衡颜色,也没有采取查表方式。

代码如下:

public static Bitmap SetGramma(Bitmap b, double gramma) { int maxGray=0; ColorDelegate grayMaxDelegate = (ref int red, ref int green, ref int blue) => { int gray = (int)(red * 0.299 + green * 0.587 + blue * 0.114); if (gray > maxGray) maxGray = gray; }; LoopPixel(b, grayMaxDelegate); double maxLight = maxGray; double g = 1/gramma; ColorDelegate colorDelegate = (ref int red, ref int green, ref int blue) => { red = (int)((maxLight * Math.Pow(red / maxLight, g)) + 0.5); green = (int)((maxLight * Math.Pow(green / maxLight, g)) + 0.5); blue = (int)((maxLight * Math.Pow(blue / maxLight, g)) + 0.5); }; return LoopPixel(b, colorDelegate); }