by Lene Nielsen

The persona method has developed from being a method for IT system development to being used in many other contexts, including development of products, marketing, planning of communication, and service design. Despite the fact that the method has existed since the late 1990s, there is still no clear definition of what the method encompasses. Common understanding is that the persona is a description of a fictitious person, but whether this description is based on assumptions or data is not clear, and opinions also differ on what the persona description should cover. Furthermore, there is no agreement on the benefits of the method in the design process; the benefits are seen as ranging from increasing the focus on users and their needs, to being an effective communication tool, to having direct design influence, such as leading to better design decisions and defining the product’s feature set (Cooper, 1999; Cooper et al, 2007; Grudin & Pruitt, 2002; Long, 2009; Ma & LeRouge, 2007; Miaskiewicz & Kozar, 2011; Pruitt & Adlin, 2006).

A persona is not the same as an archetype or a person. The special aspect of a persona description is that you do not look at the entire person, but use the area of focus or domain you are working within as a lens to highlight the relevant attitudes and the specific context associated with the area of work.

30.1 An example persona

Background

When Dorte was very young she trained as an office clerk in the accounts department in a department store in Copenhagen. She was married at the age of 21 to Jan who had just got his skilled worker’s certificate. They have two grown-up sons who no longer live at home in the combined house and workshop/office. Their sons visit frequently as they still enjoy mum’s cooking.

Dorte likes to keep up with fashion. She often goes to the hairdresser, loves vibrant colours and elegant shoes. When she reads women’s magazines, she looks for small tips that she changes and makes her own. She is always smartly dressed and stays fit.

Dorte loves travelling to faraway countries; most recently, she and her family were on a trip to Vietnam this summer. Before they went, she spent time reading up on the country and also watched the film Indochine starring Catherine Deneuve. Dorte always discusses the vacations with Jan, who would prefer to go to Rhodes with old friends, but it is Dorte who has the final say about the destination.

In an average day, she tends to drink too many cups of coffee, and when the telephone rings all the time and she can’t reach the assistants, she also tends to smoke a bit too much.

Dorte makes payments to the Danish early retirement benefit scheme and looks forward to the day where she no longer has to be the “mum” of others any more and can spend more time travelling.

Computer use

Dorte does the accounts and the bookkeeping, VAT, taxes, vacation pay, the Danish Labour Market Supplementary Pension ATP, etc. She uses a mini financial management system that she has mastered after many years of use, but sometimes the system is not completely logical.

If she were to use other systems or use new, digital reporting, she would prefer it to be demonstrated to her by someone. She feels unable to learn something new when it is just explained to her, and she dislikes reading user guides. She says it takes her a long time to study anything new and familiarise herself with it, and she tends to see more limitations than possibilities in new IT. Dorte often underestimates her IT proficiency and overestimates the time that it will take to learn something new, so she stalls before she even gets started.

If she needs IT help, her oldest son and, less often, a woman friend provide the support. The friend works in a big company and is a super-user of the financial management software.

Reporting

Dorte handles the tax cards for the business. She deals with and reports the wages, vacations, sickness benefits, and maternity leaves of the staff. She does the VAT returns and annual accounts of the company. In addition, she fills in the reports for Statistics Denmark and the Employer’s Reimbursement System AER.

Dorte does not understand the logic of the IT system and does not trust everything to happen as it should. If she sends in a return form or report digitally, she likes a confirmation saying that the recipient has received the form.

Her workday:

She is not involved in the plumbing business as a trade, but she knows all the technical terms.

She tidies things up. She does not want the others (her husband and the assistants) to make a mess in the basement where the office is as she is the one who has to look at it all day “Tidy up! Your mum does not work here!”

She digs in and sometimes has to keep far too many balls in the air at the same time.

She holds the fort, but does not get a lot of professional recognition in the company from the boss/her husband.

She answers the telephone, handles mail, deliveries of goods (including invoices and delivery letters), and email.

She handles the accounts, does some bookkeeping and writes invoices.

She makes the coffee.

She has occasional contact with the accountant.

She does the invoicing of clients.

She sends/delivers mail every day.

She sends reminders.

She handles customer contact (including damage control).

She also walks the dog.

Future goals

Dorte dreams about a future where she no longer has to work and where she can spend more time travelling. She is still debating with Jan whether they should travel or buy a summer cottage where they can live all year round when they retire.

Figure 30.1: Persona for Virk.dk. Virk.dk is a portal for digital reporting. At Virk.dk, Danish companies can find all the forms needed for reporting to the authorities.

The persona approach stems from IT system development where in the late 1990s many researchers had begun reflecting on how you could communicate an understanding of the users. In literature, various concepts emerged, such as user archetypes, user models, lifestyle snapshots, and model users — as I termed it when I first wrote about the method in 1997. In 1999, Alan Cooper published his tremendously successful The Inmates are Running the Asylum (Cooper, 1999) where the persona as a concept to describe fictitious users was introduced for the first time. Despite the fact that a vast number of articles about using personas have been written, there is no unilateral understanding of the application of the method nor a definition of what a persona description is.

30.2 Four different perspectives

The literature today offers four different perspectives regarding personas: Alan Cooper’s goal-directed perspective; Jonathan Grudin, John Pruitt and Tamara Adlin’s role-based perspective; the engaging perspective that I myself use, which emphasizes how the story can engage the reader (Sønderstrup-Andersen, 2007); and the fiction-based perspective. The first three perspectives agree that the persona descriptions should be founded on data. However, the fourth perspective, the fiction-based perspective, does not include data as the basis for persona description, but creates personas from the designers’ intuition and assumptions; they have names such as ad hoc personas, assumption personas, and extreme characters.

30.2.1 The goal-directed perspective

Cooper characterizes his persona method as “Goal-Directed Design” and maintains that it makes the designer understand the user. Thus, Goal Directed Design is meant as an efficient psychological tool for looking at problems and a guide for the design process. The central core of the method is the hypothetical archetype that is not described as an average person, but rather as a unique character with specific details.

The method focuses on a move from initial personas to final personas. In the beginning of the process, a large number of personas are created based on in-depth ethnographic research. The initial personas grasp an intuitive understanding of user characteristics. Later on, these are condensed into final personas, one persona for each kind of user. Every project has its own set of personas (Floyd et al., 2008).

A persona is defined by its personal, practical, and company-oriented goals as well as by the relationship with the product to be designed, the emotions of the persona when using the product, and the goals of the persona in using the product (hence Goal-Directed).

In other words, it is the users’ (work) goals that are the focus of the persona descriptions, e.g. workflow, contexts, and attitudes. And, as implied, the advantage of the method is that it provides a focused design and a communication tool to finish discussions.

30.2.2 The role-based perspective

The role-based perspective shares goal direction with Cooper and also focuses on behaviour. The personas of the role-based perspective are massively data-driven and incorporate data from both qualitative and quantitative sources. Often, dozens of personas are shared among projects (Floyd et al, 2008).

The starting point of the role-based perspective was criticism of the traditional IT system development approaches and of Cooper’s approach to personas. The traditional use of scenarios is criticized for lacking clarity and consistency in the user descriptions. Therefore, the critics introduced user archetypes, which can communicate the most important knowledge about the users and thereby support the design process. Jonathan Grudin and John Pruitt criticized Alan Cooper for underestimating the value of user involvement and for seeing the method as one single method that can handle anything (Mikkelson & Lee, 2000),(Grudin & Pruitt, 2002).

The role-based perspective used the criticism as a starting point to develop the method further. The most important additions are, firstly that both qualitative and quantitative materials must supplement the persona descriptions; and secondly that there should be a clear relationship between data and the persona description (Grudin & Pruitt, 2002). Personas can communicate more than design decisions to designers and clients; they can also communicate information from market research, usability tests, and prototypes to all participants in the project. Finally, the method is regarded as a usability method that cannot stand alone, but should be used in tandem with other methods. The persona description itself should contain information about several issues: how big a share of the market the individual persona takes up; how much market influence the persona has; the user’s computer proficiency, activities, and hopes and fears; and a description of a typical day or week in the life of the user. In addition to this are strategic and tactical considerations (Pruitt & Adlin, 2006).

The role-based perspective focuses on the users’ roles in the organization (Sønderstrup-Andersen, 2007). Personas are an efficient design tool because of our cognitive ability to use fragmented and incomplete knowledge to form a complete vision of the people who surround us. With personas, this ability comes into play in the design process, and the advantage is that a greater sense of involvement and a better understanding of reality will be created.

30.2.3 The engaging perspective

The engaging perspective is rooted in the ability of stories to produce involvement and insight. Through an understanding of characters and stories, it is possible to create a vivid and realistic description of fictitious people. The purpose of the engaging perspective is to move from designers seeing the user as a stereotype with whom they are unable to identify and whose life they cannot envision, to designers actively involving themselves in the lives of the personas. The other persona perspectives are criticized for causing a risk of stereotypical descriptions by not looking at the whole person, but instead focusing only on behaviour (Nielsen, 2004;Nielsen, 2011; Nielsen 2012).

The starting point for the engaging perspective is the way we as humans interact with other people. We experience specific meetings in time and place. We mirror ourselves in the people we meet. And we experience others as both identical to and different from ourselves. Also, we experience relationships that are not specific and where the person we meet is anonymous and represents a type. Here, we use our experiences to understand the person and to predict what actions he or she will perform. If the designers see the users as stereotypical representations, they mould a mental image of the users together with a number of typical and automated acts. These representations prevent insight into the unique situation of the users and reduce the value of the scenario as a tool to investigate and describe future solutions.

An engaging description requires a broad knowledge of the users, and data should include information about the social backgrounds of the users, their psychological characteristics, and their emotional relationship with the focus area. The persona descriptions balance data and knowledge about real applications and fictitious information that is intended to evoke empathy. This way, the persona method is a defence against automated thinking.

30.2.4 The fiction-based perspective

The personas in the fiction-based perspective are often used to explore design and generate discussion and insights in the field (Floyd et al., 2008). Ad hoc personas are based on the designers’ intuition and experience and used to create an empathetic focus in the design process (Norman, 2004). Extreme characters help to generate design insights and explore the edges of the design space (Djajadiningrat et al, 2000). Assumption personas are based on the project teams’ assumed understanding of their users (Adlin & Pruitt, 2006). Proto-personas originate from brainstorming workshops, where company participants try to encapsulate the organization’s beliefs (based on their domain expertise and gut feeling) about who is using their product or service and what is motivating them to do so. They give an organization a starting point from which to begin evaluating its products and to come up with some early design hypotheses (Gothelf, 2012). Pastiche scenarios create personas derived from fiction, like Bridget Jones or Ebenezer Scrooge, and help designers to be reflexive when creating scenarios (Blythe & Wright 2006). Examples of pastiche scenarios can be seen at Mark Blythe’s website.

These personas have spurred discussions about validity and value (see e.g. When does a Persona stop being a Persona and Assumption personas help overcome hurdles). In line with Adlin & Pruitt (2006), James Robertson (2008) in his article Beyond Fake Personas suggests a continuum from Persona Sketch, over Persona Hypothesis and Provisional Personas, to Robust Personas ending in Complete Personas.

30.2.5 Other perspectives

Floyd et. al. 2008 mention three additional types that they have come across: Quantitative data driven personas are extracted from natural groupings in quantitative data: User archetypes as personas are similar to personas, but more generic, usually defined by role or position: Finally Marketing personas are created for marketing reasons and not to support design.

30.2.6 Criticism

Criticism of the persona method pertains to empiricism, especially the relationship between data and fiction. The implementation of the persona method in companies has also come under fire (Chapman et al, 2008; Chapman & Milham, 2006; Portigal, 2008; Rönkkö et al, 2004).

Because the persona descriptions have fictitious elements, some find it difficult to see the relationship with real users and the way that the data used is collected and analysed. Furthermore, the fictitious elements apparently prevent the method from being regarded as scientific, as one of the criteria for a scientific method is that the study must be reproducible. This critique is based on an objectivistic scientific paradigm where science consists of statements that can be verified. In contrast to this is the interpretative paradigm where science is understood as the object of continual clarification and discussion (Kvale, 1997). The persona method is as such qualitative; deep knowledge of user needs, attitudes, and behaviour is gathered using qualitative methods. Thus this criticism can be disproven as the critics having misunderstood the starting point of the method.

The method has additionally been criticized for not being able to describe actual people as it only depicts characteristics.

When it comes to implementation, the method is criticized for preventing designers meeting actual users, as actual stories and encounters with real users are assumed to give a better understanding of the users’ needs. Yet another objection is that the method does not take into consideration internal politics, and that this can lead to limited use. Lately, the latter has been refuted, as can be seen in the suggested 10 steps to personas that involve the organisation in as many steps as possible.

30.3 The use of personas

I now provide a brief introduction to why the persona method is a useful design tool, what personas are used for, how they are constructed, how to use them, and what to consider in the communication of personas.

In the design process, we begin to imagine how the product is to work and look before any sketch is made or any features described. If the design team members have a number of persona descriptions in front of them while designing, the personas will help them maintain the perspective of the users. The moment the designers begin to imagine how a possible product is to be used by a persona, ideas will emerge. Thus, I maintain that the actual purpose of the method is not the persona descriptions, but the ability to imagine the product. In the following, I designate these product ideas as scenarios. It is in scenarios that you can imagine how the product is going to work and be used, in what context it will be used, and the specific construction of the product. And it is during the work with developing scenarios that the product ideas emerge and are described. The persona descriptions are thus a means to develop specific and precise descriptions of products.

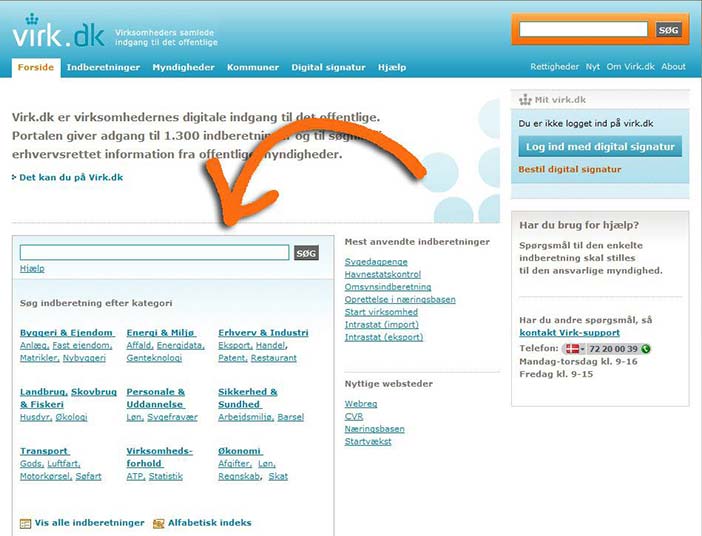

A scenario for Virk.dk could be described like this:

Dorte sits at the computer ready to handle the reporting. She goes to Virk.dk and looks at the front page. Dorte tries to take it all in. It is new and thus a little daunting, but at least it looks nice with those colours, she thinks, while at the same time she says to herself: “What do I do now I have installed my signature. I need to find the report form, but where? Well... look, in the middle of the page is a search box, maybe I can try searching for it.” Dorte writes “Apprentice refund” in the search field and launches the search. A new screen appears with a short list of hits. At the top is a link to the form she wanted.

Figure 30.2: Excerpt of scenario for Virk.dk.

In this case, the designers got the idea that there should be a search field in the middle of the homepage. This would support a shift from information push in the old version of the webpage to form retrieval in the new version.

Figure 30.3: The front page has an additional search field for Dorte, and focuses on reporting (2008). The latest version of the virk.dk portal has yet again an unclear focus on the front page as it includes both reporting and different guidelines, for example, for company start-ups

30.3.1 Personas for IT and for products

When personas are used for IT system development, it is mainly to explore interaction and navigation. On the other hand, they are not suited to describing what kind of information the system is to contain. For Virk.dk, four personas were created. One of these personas, Jesper, is an accountant. Jesper represents all the users reporting for other companies, not, however, including for example agricultural consultants. When Jesper is used in the scenario, he illustrates what demands those who report on behalf of companies have of the product, both how they think and how they would like to see the information presented. But Jesper does not represent what information and reporting forms should be available on the site. If he did, there would be no reporting forms for agricultural consultants.

In IT systems development, there are specific methods to describe the system navigation and interaction e.g. Unified Modelling Language or the user stories within agile development methods, where the scenarios are described in illustrated and narrative stories. It is quite easy to insert the personas into these methods.

As the persona method developed from a method for IT system development to also working within product development, a shift in the method occurred that has had an impact on how the method is used and what it can be used for. When personas are used for product development, the scenario takes a different path. Here, the users’ processes and interactions with the product can more easily be understood as role-playing and story-boarding, and the ways of capturing ideas are less formalized.

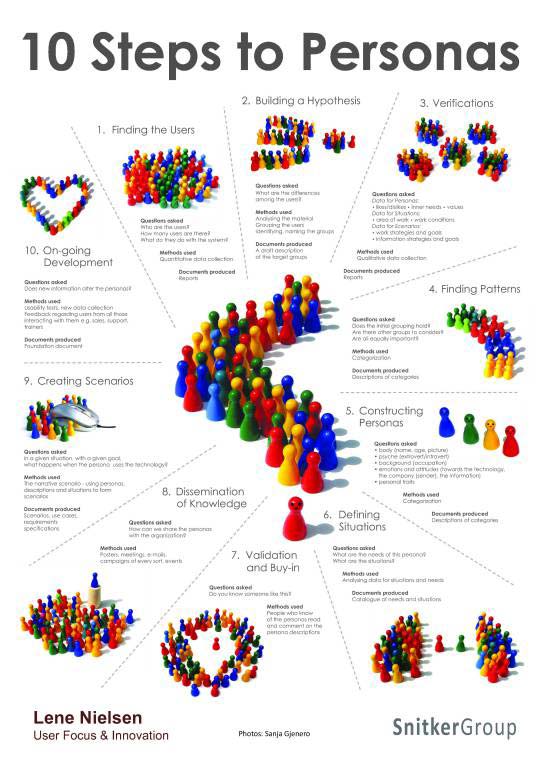

30.3.2 4 areas of importance, 10 steps to follow

The persona is ideally shaped according to user studies, and used for ideation. But the process varies; sometimes the idea comes first, and the persona is created later and used to verify or enrich the idea (Chang et al., 2008). Studies have shown that one of the main difficulties in the method is to get project participants to use it (Browne, 2011). In the following, I present a process model that sets out to cover this problem throughout the process. It contains four different main parts: data collection and analysis of data (steps 1, 2), persona descriptions (steps 4, 5), scenarios for problem analysis and idea development (steps 6, 9), and acceptance from the organization and involvement of the design team (steps 3, 7, 8, 10).

The 10 steps cover the entire process from the preliminary data collection, through active use, to continued development of personas. It is an ideal process, and sometimes it is not possible to include all steps in the project (Nielsen, 2011; Nielsen 2012).

*1. Collection of data. *In the first step, you collect as much knowledge about the users as possible. Data can come from many different sources, even from pre-existing knowledge in the organization.

2. You form a hypothesis. Based on the first data collection, you form a general idea of the various users within the focus area of the project, including in what ways the users differ from one another.

3. Everyone accepts the hypothesis. In this step, the goal is to support or reject the first hypothesis about the differences between the users. This happens by confronting project participants with the hypothesis and comparing it to existing knowledge.

4. A number is established. In this step, you decide the final number of personas.

5. You describe the personas. The purpose of working with personas is to be able to develop solutions based on the needs of the users, which you do through preparing persona descriptions that express enough understanding and empathy for the readers to understand the users.

6. You prepare situations. As already mentioned, the method is directed at creating scenarios that describe solutions. To that purpose, a number of specific situations that could trigger use of the product are described. In other words, situations are the basis, or the precursors, of a scenario.

7. Acceptance is obtained from the organization. It is a common thread throughout all 10 steps that the goal of the method is to involve the project participants. This means that as many as possible should participate in the development of the personas and that it is important to obtain the acceptance of the participants of the various steps. That is why all should contribute to and accept the situations. In order to achieve this, you can choose between two strategies: You can ask the participants for their opinion, or you can let them participate actively in the process.

8. You disseminate knowledge. In order for the method to be used by the project team, the persona descriptions should be disseminated to all. It is, therefore, important early on to decide how this knowledge is to be disseminated to those who have not participated directly in the process, to future new employees, and to possible external partners. The dissemination of knowledge also includes how the project participants will be given access to the underlying data.

9. Everyone prepares scenarios. As previously mentioned, personas have no value in themselves. Not until the moment where the persona is part of a scenario - the story about how the persona uses a future product - does it have real value.

10. On-going adjustments are made. The last step is the future life of the persona descriptions. The descriptions should be revised regularly, approximately once a year. There can be new information, or the world could change and new aspects may affect the descriptions. Decisions have to be made whether to rewrite the descriptions, or add new personas, or whether some of them possibly should be eliminated.

Figure 30.4: The poster covers 10 Steps to Personas

30.3.3 Why stories matter

One of the perceived benefits of personas is that they give the design team a mental model of a particular kind of user, which allows the team to predict user behaviour. The personas evoke empathy with users and prevent designers from projecting their own needs and desires onto the project (Floyd et al., 2008). For the persona to evoke empathy, the description needs to be crafted in such a way that the reader can imagine a real person, understand this person’s needs and desires, and predict the person’s future actions. In the following, I go into more details about how personas and scenarios are tightly interlinked with storytelling to evoke empathy and identification. Here, I am thinking both of the relationship between the fictitious characters and the story and the general narrative structures.

Using narratives is nothing new within IT system development (Madsen & Nielsen, 2006), where stories have been suggested as a starting point to collect data and as a method to theorize over various project types and project phases. At the same time, focus on stories can play a part in providing insight into what goes on outside and below the official course of events. Thereby, the many, often contradictory and competing, stories and interpretations that circulate in an organization can be revealed. Stories can also be used when you want to theorize about organizations, IT systems, and IT system development. An organization can be seen as a collective narrative system where members construct and play out sequences of events on an on-going basis, both individually and together, to be able to remember and to create meaning in past, present, and future events (Boje, 1991; Boje, 1995). These sequences can be used in the process of structuring both the IT system development process and the IT system itself. Here, the narrative contributes to establishing a partnership and a common understanding of the players involved and their goals. This applies in relation to both the development and the presentation of the system to the user (Gazan, 2005). Stories work on several levels, and also provide templates for gathering and analysing empirical data. This happens in interview situations when you need to determine system requirements. The developers can focus on the users’ stories about existing and future practice, analyse them, and thus become more aware of requirements (Alvarez & Urla, 2002). These requirements can later on be described in narrative scenarios that are easy to relate to and easy to remember. The scenarios draw on our ability to create meaning individually and together, and to arrange and concentrate information in a narrative form (Carroll, 2000). Subsequently, the stories can be used to analyse the process, the mistakes that occurred, and the political implications of the development and implementation process (Brown, 1998; Brown & Jones, 1998).

30.4 Field data and the engaging persona

To describe users as personas helps designers to engage in the users during the entire design process. It enables the design team to engage in the user and to focus the design on the user. But the descriptions can conflict with the preconceived perceptions the designers have — their stereotypical images.

When we encounter a stranger, we have a tendency to see the person as a stereotype. We do not see the person as possessing a unique constellation of characteristics, but add him to a previously formed category (Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2001). The stereotype is built on knowledge of previous meetings with others and ordered into categories that form the basis for the stereotype. One definition of stereotypes is that they are “socially constructed representations of categories of people” (Hinton, 2000). The stereotypes function as mental pictures for the designers, but being stereotypes, they prevent identification with the described person. The descriptions thereby influence the value of the scenarios as means to investigate and describe a possible future solution.

To move designers away from stereotyping and to get them to engage in the personas puts demands on the descriptions. The field data for personas has traditionally focused on behaviours and demographics (Goodwin, 2008) or goals and tasks in work-related environments (Carroll, 2000). Cooper et al. (2007) list three types of user goals that should be included in the persona descriptions: experience goals, end goals, and life goals. To collect field data for the engaging personas demands an awareness of other kinds of information such as background, psychology, emotions, and character traits.

Within the field of HCI, ethnographic material is collected, interpreted, and communicated, but the act of communicating the data to a design team is often overlooked. The foundation document (Pruitt & Adlin, 2006) is an example of a recommendation for what should be included in a material that can support the personas, but the choice of material does not reflect the process of perceiving the material.

The creative process of writing engaging personas is grounded both in the writer’s previous experiences and in the field data. To introduce field data to designers is an act of communication that involves both a selection of the data to present and selecting the form in which it is to be presented. During the presentation, the presenter must be aware of how the data is received and interpreted. As human beings we have a tendency to categorize persons, but by being aware of this and adding information that works against the tendency, we might prevent designers from conceiving stereotypes.

30.4.1 Engagement

INT. - THELMA’S KITCHEN - MORNING

THELMA is a housewife. It’s morning and she is slamming coffee cups from the breakfast table into the kitchen sink, which is full of dirty breakfast dishes and some stuff left from last night’s dinner which had to “soak”.

She is still in her nightgown. The TV is ON in the b.g. From the kitchen, we can see an incomplete wallpapering project going on in the dining room, an obvious “do-it-yourself” attempt by Thelma.

Figure 30.5: Beginning of the film script: Thelma and Louise (Khouri, 1990).

But what is it to engage a designer? And how can a persona description evoke empathy? In the following, I present a framework that emanates from a theoretical understanding of fictional “engaging characters” and character building and writing. Furthermore, it encompasses what elements a character description should include and how in the reading process we engage with a character when, as readers, we comprehend a written description of a human as complete. Take a look at the excerpt from the beginning of the film script for Thelma and Louise. The description of Thelma is quite vivid and in few lines tells the reader about her state of mind (unhappy), her status (housewife) and her character trait (sloppy).

The character perspective in fiction has commonalities with the persona description as the narrator is withdrawn and invisible. The invisible narrator is also seen in the script example where the description of Thelma is not seen from any specific perspective, but a neutral author comments on the scene by describing details that say something about Thelma and her surroundings.

The persona in the scenario has a function similar to the function of the character in the film script; it is through the description of the character that we understand the character’s actions and motivation for action, and it is the character’s actions that move the story forward.

30.4.2 Levels of engagement

To create an engaging persona is to provide the reader with a vivid description of a user, so vivid that the reader can identify with the user throughout the design process. The term “identification” covers the processes of recognition, alignment, and allegiance (Smith, 1995).

Recognition is the information that enables the reader to construct the character as an individual and human agent.

Alignment is the process whereby the reader is placed in relation to the character’s actions, knowledge, and emotions.

Allegiance is not only the moral evaluation the reader produces of the character, but also the moral evaluation the text allows the reader to produce. Allegiance depends on access to the character’s state of mind and the reader’s ability to understand the context wherein the action takes place.

The engagement is first and foremost provided through the ability to recognize — a recognition that originates from both the material presented and the reader’s knowledge that goes beyond this. The more material presented the less the reader has to draw on his own experiences.

What is not presented to the reader in the description of the persona, the reader must create himself from inferences, which are added to the story, so to speak.

To enable engagement in the character, the description of emotions as well as of alignment and allegiance is derived from the material. From the reader’s point of view, the description of the persona has certain demands, but as the engaging persona is to be part of a scenario, the narration generates demands of the character description too.

In order for the designer as reader to engage in the persona, the text must give access to:

Information that enables persona construction;

Information about the emotional status of the persona;

Information about context that enables an understanding of the character.

30.4.3 Flat character or rounded character

To the reader or viewer of fiction, the two basic types of stories are well known. The plot-driven story is seen in most action films where the hero has very few character-traits and the story moves from one action to the next. The character is defined as a flat character. In contrast to this, the character-driven story has a character that is described with several traits, and it is the development of the character that moves the story forward. This character is defined as a rounded character.

The difference between the characters in the character-driven and the plot-driven stories are the number of traits. In the plot-driven story, the character has a limited number of traits, and they function as catalyst for actions. This makes the character highly predictable and creates a flat character in a plot-driven story (Chatman, 1990).

In the character driven story, the character has multiple traits. The tension between the character traits creates unpredictable actions and this determines the story development.

30.4.4 Construction of the rounded character

A description of a human being should include physiognomic dimensions as well as sociological and psychological dimensions. Each of these has an impact on the character’s behaviours and actions. The descriptions of physiognomy, sociology, and psychology enable an understanding of the motivation behind the persona’s actions in the scenarios. The dimensions encompass both past and present, both the self and relations to others.

“If we understand that these three dimensions can provide the reason for every phase of human conduct, it will be easy for us to write about any character and trace his motivation to its source.” (Egri, 1960: p. 35).

Thus the character possesses both personal (inner) and inter-personal (social, public, and professional) elements. It is the diversity in experiences that constitute the character. All characters have personal needs and goals as well as interpersonal wishes and professional ambitions. These help define the character and create its own demands, restrictions, and privileges.

This, as well as the understanding of the rounded character, has several implications for the creation of the persona description:

The character develops in the story.

The character has two or more traits that interact.

The character belongs to a specific time and specific culture and interacts with the culture.

The persona description is characterised by:

More than one character trait;

Psychology, physiognomy, and a social background;

Personal needs and goals, interpersonal wishes, professional ambitions;

Context.

Furthermore the persona belongs to a specific time and specific culture and interacts with the culture, and the persona develops in the scenario.

The understanding of the rounded and engaging characters puts demands on the data from the field studies. Observations of work processes and segmentation of users as skilled versus non-skilled users do not provide the writer with the necessary information to describe the character traits and psychology of the persona. As the rounded character incorporates personality, emotions, and actions, these elements should also stem from the field data. During research, information about the users’ surroundings, character traits, emotional status, and background, as well as common demographics, actions, goals, and tasks should be observed.

30.5 Scenarios and stories

The move from creating engaging personas to scenarios reflects the move from a static character description to an active character in a story — a narrative. In the following, I draw on an understanding of narratives as both a process (mental story construction) and a product, both performance and text (Ryan, 2003; Boje, 1991).

There is an on-going discussion of what a narrative is, but it is agreed that it includes time — it is a way for humans to organize time. Is a narrative the barest organization of time as suggested by Abbott (2002) e.g. “She took her bicycle”? Or does it include causality, as suggested by Cobley (2001) e.g. “She took her bike and was hit by a bus”? I will not participate in the discussion, but take a pragmatic standpoint from a scenario point of view. In the scenarios, the narrative must include causality, as the focus is on the relationship between how the user’s action gives rise to system reaction and how system action provokes user reaction.

There is a distinction between narrative and story. The narrative is the organization of events, while the story includes prior events or events the reader must assume or guess.

**Narrative: **A movement from a start point to an end point, with digression that involves the showing or telling of story events. Narrative is a re-presentation of events and, chiefly, re-presents space and time.

Story: All the events which are to be depicted in a narrative and which are connected by the means of a plot (Cobley, 2001).

For a text (in the broadest sense of the word) to qualify as a narrative, it must (Ryan, 2003):

create a world and populate it with characters and objects; the world must undergo changes of state that are caused by non-routine physical events: either accidents/happenings or deliberate human action;

allow the reconstruction of an interpretive network of goals, plans, causal relations, and psychological motivations around the narrated events.

30.5.1 Stories and meaning

When we experience incidents, we try to understand and extract a meaning from the incidents. This meaning can either have the construction of a story with sequences organised in a narrative and linear structure or as meaning organised in a logical structure (Bruner 1990). When we read a scenario, a similar process begins. We are handed story elements that make us put together a narrative. Some information we do not receive as story elements; they are to be inferred from our expectations, knowledge of the area, and cultural background.

The creation of the narrative is an inter-subjective process constructed by the reader from presumptions and inference. An example: The woman takes the knife. The man hits the woman.

We infer a causal connection between the two elements of action, and we assume that the two actions will spur further action.

The narrative becomes different if the story-elements are the same, but are presented in reverse order, as in this example: The man hits the woman. The woman takes the knife.

30.5.2 Personas in stories - scenarios

In IT system development, the persona description is used as the foundation for outlining a scenario that investigates the use of an IT system from the particular user’s point of view. The persona method authors suggest different types of persona-scenarios. Cooper et al. (2007) suggest a progression from initial, high-level scenarios to more and more detailed ones with increasing emphasis on the user-product interaction. In order to describe this progression, they distinguish between problem scenarios, which are stories about a problem that exists prior to the introduction of technology, and design scenarios that convey a new vision of the situation after the introduction of technology. Pruitt & Adlin (2006) refer to Whitney Quesenbery’s (Quesenbery 2006) definition of different types of personas and to scenarios with different levels of detail placed in a continuum between evocative and prescriptive scenarios as well as along the development process. Mulder & Yaar (2006) focus exclusively on web development and propose one type of scenario that describes a persona’s journey through a website. The authors provide different lists of elements that could/should be included in a ’complete’ or ’good’ scenario. Below is presented an overview of these authors, the scenario elements they propose, and the scenario element definitions they give, if definitions are given (Madsen & Nielsen, 2009)

Cooper (Cooper et al., 2007)

Quesenbery (Quesenbery, 2006)

Pruitt & Adlin (Pruitt & Adlin, 2006)

Mulder & Yaar (Mulder & Yaar, 2006)

PERSONA

A persona encapsulates a distinct set of behaviour patterns

Characters The persona is the main character, but other characters might also be involved.

Specified user A persona.

Document the mission from the persona’s point of view. Others can be around, influencing the decisions.

CONTEXT

In what setting will the IT system be used?

Set the scene: Where is the persona? When does it happen? Who else is around?

BEGINNING

Context/situationThe beginning of the story, motivation for what happens, and a focus on what the persona is trying to do.

Particular task orsituation.

Establish the goal or conflict. Conflict: inner or outer conflict triggers the visit to a website.

ACTION

Is the personainterruptedfrequently? Will the IT system be used for extended amounts of time? Will other ITsystems or products be used? What are theprimary activitiesthe persona needs to perform to meet his or her goals? How muchcomplexity is permissible, given persona skill and frequency of use

Plot/action Focus on what happens during the scenario and what influences the decisions the persona has to make.Facts Gathered from user research.

Features orfunctionalityReferences to specific features or functionality the persona will need and/or use.Procedure or task flow information

Overcome crisisalong the way.Describe intermediate steps and decisions.Does the persona use other sites, email, phones etc.?How does the persona feel about the experience?

ENDING

What is the*expected *end result of using the IT system?

*Resolution The ending situation and a focus on what has changed during the story.

Clearly definedoutcome *or goalfor the task.

Achieve resolution Reach denouement - what happens after the resolution?

Table 30.1: An overview of the various scenario elements according to different authors.

The table shows that the lists of scenario elements are somewhat similar, but also that only Quesenbery (2006) and Mulder & Yaar (2006) explain the elements that should be included in a scenario — and this only in a brief manner. Mulder & Yaar (2006) state that the scenario elements they outline are the classic components of storytelling. However, they do not explain what classic storytelling is. In general, the persona literature is clearly inspired by, but does not explicitly refer to, narrative theory as an established knowledge base and source of already defined (if controversially discussed) key concepts, such as story elements. It is relevant to look more closely at the narrative aspect of persona-scenarios and to draw more explicitly on narrative theory in doing so.

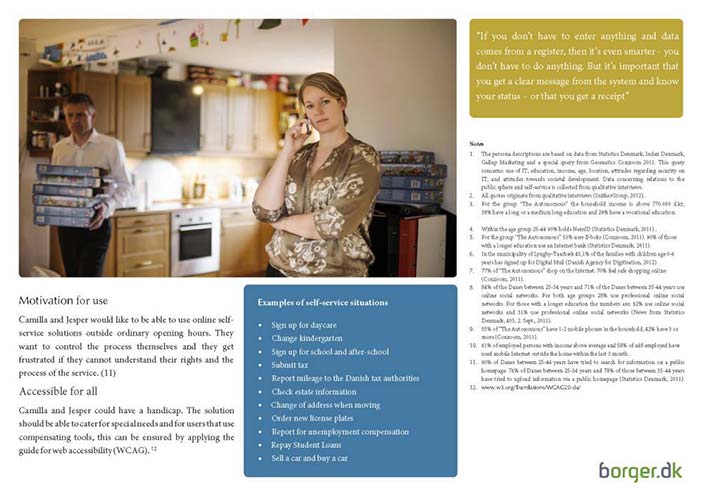

Figure 30.6: Personas for borger.dk. Each persona description has examples of situations that act as a starting point for scenarios. In this case, e.g. change of kindergarten, and change of address. Note that in this case, the persona is a couple.

30.5.3 The story structure

Basically, a story includes setting, goal, plot, and solution. It evolves in a dramaturgy of beginning, middle, and end. For the scenario, the dramatic elements are:

The beginning presents the user and what the persona wants to achieve.

The middle describes what the user does, e.g. the navigation and the information that is offered. And it describes the persona’s motivation for pursuing the goal.

The end describes whether the persona succeeds in his or her intentions.

The creative part of scenario construction is crucial; it is during this process that the field data evokes design ideas. Whether writing or drawing, producing a scenario can take place in a shared setting and as an act of communication. The scenario explores the creative situation, and this can be compared to the productive notion Tolstoy had when writing Anna Karenina:

“(...) after Vronsky and Anna had finally made love and Vronsky had returned to his lodging, he, Tolstoy, discovered to his amazement that Vronsky was prepared to commit suicide.” (Abbott, 2002: p. 18)

It is the acquaintance that Tolstoy has with the Vronsky character and the narrative that in itself provides the action. In this instance, it reflects the circumstances and the traits of the character, but when the story acts as a motor for creativity, it can both provide descriptions and solutions and, as here, also carry the writer away.

As the creative process has this ability, it becomes necessary for the producer of the scenario to look for consistency and closure in both the description of the persona and the scenario. In other words, the producer needs to look upon the scenario from a reader’s point of view to try to understand the story as an outside reader might understand it.

30.5.4 Story elements: Events

Events are essential to stories. A narrative is made up of both constituent events that are necessary for the story and supplementary events that do not seem essential, but add flavour and enrich the story (Abbott, 2002).

Setting is another common ingredient in stories. The setting is optional; “she took her bike and was run over by a bus” does not include a setting, but to a scenario, the setting is inevitable. It is the setting that pinpoints where the use takes place, the surroundings that may influence the use, the time of day, and other elements of context that might influence the use.

Dorte sits at the computer ready to handle the reporting. She goes to Virk.dk and looks at the front page. Dorte tries to take it all in. It is new and thus a little daunting, but at least it looks nice with those colours, she thinks, while at the same time saying to herself: “What do I do now,” I have installed my signature. I need to find the reporting, but where?“ Well... look, here in the middle of the page is a search box, maybe I can try searching for it” Dorte writes “Apprentice refund” in the search field and launches the search. A new screen appears with a short list of hits. At the top is a link to the form she wanted.

Figure 30.7: Excerpt of scenario for Virk.dk, 2007

If we again look at the scenario for Virk.dk, the setting is known from the persona description. The scenario includes the following events:

Dorte writes "virk.dk" and presses the enter key.

The webpage loads.

She searches for a form.

She gets a list of hits.

These are the events that lay the foundation for the system design.

30.5.5 Story elements: Closure and resolution

When a narrative resolves a conflict, it achieves closure (Abbott, 2002). Closure can be both for a single event and for the whole story. Resolution is one way of obtaining closure. When we read a story, we want to have closure to get answers to questions and to experience the end. We have a desire for the end. As Brooks puts it: “...narrative desire is ultimately, inexorably, desire *for *the end” (Brooks, 1984: p. 52). As we write the scenario, we do not know the end, but we have a desire to find the end through the creative process. During discussions and writing, endings will be created; if open-ended, the scenario can be an agenda for dialogue.

Scenario reading differs from scenario writing. As a natural cause of the reading process, closure and resolution is craved. If it is not provided, the reader will make it up (Abbott, 2002) — in the scenario example, the reader depicts Dorte in a setting: is she in her office — or sitting with her laptop in front of the television? If the scenario does not provide the information, the reader will make the setting up in the urge to obtain closure.

30.5.6 Story elements: Voice

The voice — whom do we hear — can be either a first person narrator or a third person narrator. The first person narrator “I took a bicycle” is limited to the view of the person, while the third person narrator “she took a bicycle” has the possibility to include comments that the person cannot know of — “she took a bicycle, but what she didn’t know was that the evil person had put a GPS on it to track her traces”.

Some suggest use of a first person narrator, e.g. (Mikkelson & Lee, 2000). Even though this provides information about the language used by the persona, the downsides are bigger. The possibility of adding omnipotent comments to the scenario should not be ruled out as they can function as containers of information that are not accessible for the persona. If dealing with scenarios for more personas, it can be very difficult to distinguish one character from the other with the use of “I”. Furthermore, it takes a very skilled writer to imitate and create a consistent language. This can be experienced in the scenario excerpt where the dialogue is very extensive and not as subtle as real-world dialogue.

30.5.7 Story elements: Plot

Plot is inevitable in a story; it is the linking of events in the plot that keeps the story moving (Cobley, 2001). Both plot-driven and character-driven stories include action; what separates them is the depth of the persona portrait. In the character-driven story, the character is seen as a personage rather than somebody who is the product of the plot and just participating in the story development. Instead, it is the character development that creates the story development, and the story development that spins the plot. If the designer is to engage with the persona, the scenario should include a strong central character with goals and desires that need fulfilment during the story, thus resembling the character-driven story.

30.5.8 Story elements: Obstacles

Understanding the obstacles of the users when using the product is essential in order to develop and redesign products. Often, the obstacles become visible during the collection of data, and they can stem from the system itself and from the surroundings. If we look again at the excerpt of the scenario for Dorte, the obstacle of installing a digital signature is not examined. It is a pre-requisite that she has installed the signature, and the story begins from this point. But how likely is it that she can do this herself when she needs help from her son to do her first digital reporting?

You often see scenarios, especially in IT, where just giving the persona an IT system solves all problems. I call this type of scenario “happy scenarios” as they always have a happy ending. They lack obstacles, and the solution is always that the IT product will make everything much easier. When you read this type of scenario, they seem unrealistic because of the lack of obstacles.

30.5.9 An overview of the scenario elements

The overview below is inspired by Jean Mandler’s reflections on the story form (Mandler, 1983). The story begins with a setting in which characters, location, problems, and time are presented. After this presentation, one or more episodes follow, each having a beginning and a development towards a goal. In the opening episode, the character reacts to the introductory events, sets a goal, and outlines a path to reach the goal. Each episode focuses on the goal, the attempts to reach the goal, and the obstacles in the way of reaching the goal. The attempts are understood as the causes of the outcome. Each episode links to the overall story, thereby building up the plot.

NARRATIVE ELEMENTS

NARRATIVE ELEMENTS IN A SCENARIO

Character(s): a protagonist as well as minor characters. A character can be any entity that has agency, that is, involved in the action.

In scenarios, the persona is the protagonist. (In scenario-based design, the main character and protagonist is the IT system.)

Time: both the time in which the actions take place, e.g. the future, and the story development over time - beginning, middle, and end.

Most scenarios are set in present time, but they can also concern a distant future.The story time can last minutes, days, months, etc.

Problem: a loss, a need, a lack of something, an obstacle to overcome, a conflict.

The persona has a problem.

Setting: presentation of characters, location, problems, and time.

The scenario begins with a presentation of the persona, his or her problems, the place where the action takes place and the time (present time/distant future).

Opening episode: the character reacts to the problem, sets a goal, and outlines a path to the goal.

The persona defines the goal and starts to act.

Episodes: development toward the goal. Episodes consist of:Beginning

Attempts

Events (accidents, obstacles, happenings, deliberate human actions)

Development

The scenario develops through a sequence of episodes that concern the problem, the goal and the attempts to reach the goal, the events involved in these attempts, and the obstacles hindering fulfilment of the goal.

Resolution: the problem is solved and the goal is reached - or it is not.

There are two types of scenarios - one where the problem is solved and the goal is reached, and one where they are not.

Plot: the linkage and order of the episodes.

Most scenarios are presented in a linear manner, without deviations from the story line.

Overall story: starts with a beginning, goes through a middle, and arrives at the end.The overall story is sensitive towards what is considered ordinary social practice within a given culture and explains deviations from accepted social practice.

Each episode links to and has to be meaningful in relation to the overall story.The scenario has to explain why non-routine actions and events happen and how they are dealt with.

Narrator’s perspective: The narrative is told by someone.

Most scenarios are told in third person allowing the narrator to be omnipotent.

Table 30.2: An overview of the story form and a ’translation’ hereof to a scenario context (Madsen & Nielsen, 2010)

30.5.10 Benefits and pitfalls

To sum up, the benefit of the scenarios are that they are specific and use a language that is easily understood and accessible for both users and designers. This is a contrast to other models that require knowledge and expertise in order to be understood. The scenario enables a design process focused on use and explains vividly why a system is necessary. The scenario enables an understanding of the experiences that most likely results in a successful accomplishment of theuser’s goals and it offers a task-oriented decomposition (Sutcliffe, 2003; Bliss, 2000; Jarke, 1999; Kyng, 1992).

This overview suggests a shared understanding of the scenario method as a means to provoke discussions and generate ideas in a specific language easily shared by users and designers. It enables experiences to be shared and anchors the empirical data in a specific form.

The downsides of the scenario are that it can confirm beliefs and create obsession with details, and it can create a false reassurance, as it is hard to know when the design area is covered. The downside is also a lack of clarity in evidence of field data and a lack in focus on the user.

The benefits of the scenario are:

The scenario enables specific knowledge and supports reflection in action.

It supports communication and shared understanding between the members of the design team and between users and designers. It can help design knowledge to accumulate across problem instances when categorized and abstracted.

It supports idea generation, including abandoning of design ideas and is easily revised and written for many purposes and at many levels.

It constitutes a theoretical anchoring of an empirical “chaos”.

(Bødker, 1999; Bødker & Christiansen, 1997; Carroll, 1999, Carroll 2000; Erickson, 1995; Sutcliffe, 2003).

The downsides of the scenario are:

The scenario can create a false sense of assurance that all aspects are covered by a small number of scenarios and can supply minimal evidence to confirm a belief.

As the scenario is detailed, it can bias people away from the big picture and create obsession with unnecessary details.

The scenario method lacks clarity in defining the user: it does not capture the essence of the user as representation is covered by attributes such as age, job, and title and might not faithfully represent the user’s tasks and contexts or the user’s interests.

The method lacks focus on the user and does not create engagement.

The scenario design tradition lacks evidence of how data is gathered and on which basis the scenarios are formed.

(Grudin & Pruitt, 2002; Mikkelson & Lee, 2000; Nardi, 1996; Nielsen, 2003; Sutcliffe, 2003).

Alan Cooper (1999) links personas and scenarios. He describes the scenario as the investigation of tasks. “A scenario is a concise description of a user using a software-based product to achieve a goal” (Ibid p. 179), where the goals stem from the persona description.

Even though it seems natural that there should be a link between personas and scenarios, they have often been viewed as separate methods.

30.6 A useful tool around the globe

In 2010, Forrester claimed that a redesign with personas can provide a return of investment on up to four times (Drego & Dorsey, 2010). In a later study, it was demonstrated that a number of areas affect the success of the method (Browne, 2011). The criteria of success are:

Personas should be used for identifying concrete decisions and products that should be based on personas.

Qualitative research should have high priority.

The persona descriptions should be properly made.

The descriptions should be used for design decisions.

The descriptions should be evaluated and updated at regular intervals.

Reported failures seem to be due to:

Sloppy research and data gathering.

Many do not understand the method and think it is the same as demographically based segmentations and customer profiles.

Too few resources are put into the project.

The quality of the persona descriptions is inconsistent. Some are well-written stories and engage stakeholders using supportive material. Other descriptions are unrealistic and badly written and do not think of those using the descriptions.

Those who are to use the descriptions find it hard to understand how to use them.

Similar studies have been carried out in Denmark in 2009 (Vorre Hansen, 2009) and 2011. These studies showed that there is a difference between consultant agencies and in-house development as some agencies have a world-view or a lens with which they collect and analyse the data, e.g. motives and barriers for product use or shared values between sender and recipient. For in-house development, the specific values seem not to be present. One finding was that those interviewed in the study assessed that personas should be checked regularly and updated if necessary every 1-2 years.

The interviewed judged the value of the method as well as the challenges. From the studies, patterns of what the companies use the method for appeared. Personas are used for a variety of purposes and with different values:

In concept and product development, to maintain focus on the users in the entire development process. The personas can be integrated directly in the development processes, in preparing test scenarios and in concept testing. Some companies use them for requirement specification.

As a strategic tool. Some companies use them as a strategic tool to target future user groups. The method makes it possible to make strategic decisions regarding target groups. The companies are able to identify both their primary target group and groups that are either secondary groups ornotto be addressed.

They are used for recruitment of users for usability tests, interviews, and focus groups, and for preparing test scenarios and questionnaires.

The method offers a common communication platform for the company or internally in the project group. It ensures that discussions are based on a common understanding of the user and not based on pre-existing understanding of and personal experience with the users.

It provides a qualified understanding of the users. The method communicates data and thus increases the internal knowledge about the target groups of the company.

The method shifts focus from the well-known users to the lesser known, thus ensuring that the target groups that the company knows less about are also included in the deliberations of the projects.

It can focus and validate the final product. By including the users early on in a development process, the likelihood that there will be recipients for the product is greater.

The method creates documentation and argumentation for specific solutions. To be able to refer to a specific persona and the underlying data is part of supporting the choice of one solution over another.

It supports working across departments. Especially in larger organizations, the method can contribute to abolishing “silo” thinking. When focus is shifted from the organizational structure to the users, the method makes different departments collaborate.

It has a long shelf life. Personas can be included in more and in new projects long after their development.

Surprising areas of application. The persona descriptions can be used in areas that are unexpected e.g. to develop test scenarios and questionnaires.

A number of challenges are reported, especially in the following areas:

Making the method visible in the organization. It can be difficult to disseminate knowledge about and ownership of the method to other departments in the company.

It is challenging to get supporting knowledge about the persona method as there is no exchange of experiences across companies and there is no platform for knowledge sharing.

It is difficult to differentiate the communication and to operationalize the personas to various work groups; for example, some groups might emphasize that they have insight into the data behind the personas, while other groups dislike the fictional elements. There is a lack of tools to develop differentiated forms of communication.

Often, the method is dependent on individuals, and it is a challenge to anchor the method in management. This creates a feeling that the method depends on individual members of staff, and if they disappear from the department, the method will not survive.

It may also be difficult to get external suppliers to use the method and to communicate personas to them. It is important to get the suppliers to use or at least know the method as in certain contexts it is the subcontractors that develop the final product.

Maintaining the persona descriptions is also a challenge. Often, there is no one employee responsible for updating the personas so the descriptions are updated at random. Funding for this might also be difficult as there is no budget for updating, but only a budget for the actual persona development project.

In the book "Personas - User Focused Design" (Nielsen, 2012), I asked 6 UX professionals from Australia, Brazil, Finland, India, Russia, and UK, to give a short overview of the status of persona use in their country. The common experience is that it is often large companies that are drivers: banks, newspapers, insurance companies, or government bodies. Some companies report from product design (Japan, India), while most use still seems to be within IT-related areas. Few companies develop their own method, and many refer to Alan Cooper and the goal-directed design method. The Russian UIDesign Group had to translate and define the term of personas into Russian when they started and has now developed its own method that has a strong focus on the use of personas for requirement gathering. Around the globe, there seems to be a uniform format of the descriptions, with photos and short descriptions of an individual character. While most companies report that the use of the method is still in its infancy, Daishinsha Inc. in Japan has used the method for product innovation since 2000, following an introduction from Forrester research and Alan Cooper.

30.7 Future directions

As we have seen, the persona method is not a uniform method, and it is used in different ways. With a shift from a method used for IT systems design to include more areas such as marketing and communication, the method is constantly evolving. Some companies do not fully understand the potential of the method as a design method and instead devise marketing archetypes and call these personas. I hope that in the future much more focus will be on use, on the scenarios, and on a better understanding of how data collection should be part of proper persona descriptions.

One constant in the persona method has so far been its focus on users and not on including users in the design process, as can be seen in participatory design and co-design (see e.g. Ned Koch’s chapter on action research). In the following, I present a novel way of using personas for innovation and ideation where the users are involved in the design process — personas as part of role-playing scenarios with users (co-design). Furthermore, I present an experiment with actors acting as personas to help designers become immersed in and understand the daily lives of the personas (enactment).

30.7.1 Personas and co-design

Arla Foods a.m.b.a., the leading dairy company in Scandinavia, wanted to innovate within the, until then, unknown area of canteens. For the purpose of creating new products from user knowledge, an innovation process was launched. It consisted of: scientific data gathering, customer data gathering, and data analysis. From the analysis, two personas were produced. The material was used in an innovation workshop lasting two days. The participants were to use the persona descriptions in various scenarios and come up with product ideas based on the scenarios.

The innovating participants were concept developers, marketing managers, engineers, and canteen managers. Even though the canteen managers came on the second day of the workshop, they entered the groups without hesitation and became engaged in the creative process. It was easy for them to relate to the persona descriptions and they felt on equal footing with the designers. This resulted in more than twenty ideas out of which four were picked for further development.

Another case of users innovating with personas is from a student session. This case had only one participant, but proved as successful as the first industrial case. The aim was to develop a tool that could support communication between soccer trainers, children, and parents. Prior to the session, data was gathered from observations and focus groups.

From this, two personas that had different behaviour and media use were created as well as a number of scenarios that varied in situation and context. The user was asked to go through all the scenarios from the point of view of the two personas, with the intention of creating novel solutions.

Figure 30.8: The user explains to the moderator how the persona will act in the given scenario.

The participant, the mother of a soccer-playing child, had no problem in switching between the two personas, even though only one resembled herself. She was able to draw on her knowledge of other parents and their preferences and behaviour, but when she acted as the persona that resembled herself, she often commented on the likeness, how she herself would react, and her own needs.

The two cases show how users 1) are able to act as personas and be as creative as professional designers 2) use their understanding of the area in focus to create scenarios from both the perspective of personas that are similar to them, and from personas that are different from them because they are familiar with different behaviours within the given design area.

It also shows how the users immediately are able to role-play through the scenarios and to do this both alone and together with designers and other project participants.

The use of personas enables project participants to discuss from the same understanding of context and needs and at the same time allows the users to enter the discussion as experts and relate to the innovation from their concrete knowledge of culture and work tasks. This way, the personas take the focus away from the users as the single domain experts — as is seen in participatory design — and aligns designers and users in the role as innovators.

30.7.2 Persona actors

A recent experiment by Line Mulvad, shows how actors can perform as personas and thereby enhance the engagement and understanding of the users. For the website borger.dk that is aimed at all citizens in Denmark, six personas were developed during spring of 2012. The personas vary in their knowledge of what it takes to be a citizen, their understanding of the public sector, their use of and competences within IT, and their use of digital self-services. As an experiment, Line Mulvad, producer and actor, took two persona descriptions as the point of departure - a male carpenter, age 44, single parent who found reading long text difficult; and a female healthcare assistant, age 56 and originally from Bosnia, thus speaking Danish with an accent. From the descriptions, the producer and the two actors improvised a series of scenes that introduced the personas as characters and a couple of scenarios that showed the problems they have in using public websites — for both, when it comes to understanding the language, and for the woman, the understanding of the systems. All was filmed and edited into two small films of app. 4 minutes length. The films had a dogma style with hand-held camera and the actors talking to the camera, which gave an authentic impression.

Figure 30.9: The actor Jeppe Christoffersen plays a carpenter who has problems with reading long texts and therefore wants to be absolutely sure he has done it right when he reports digitally.

The films were shown to an audience, and the following discussion showed that almost all felt that they got a better understanding of the personas from the movies than from a written description; they felt it was easier to engage in the personas and come up with design ideas. Also, the spectators never felt that they were watching actors, but were convinced that they were watching real users. A downside of this method is the second part of the movie, which incorporated a present-day scenario. The scenarios gave the film action and plot, but as the present day scenarios will change when redesign is being performed, they do not have a long-lasting effect. In the future, we will have to test the difference between the written persona descriptions and the enacted descriptions, and work out how to incorporate action and drama without focusing on problems from the present day scenarios. But by using actors instead of real users, it becomes possible to focus on exactly the information and problems you want to put forward.

30.8 Where to learn more

There are very few books written on personas, but many papers based on single case studies. Here is an overview of the books I have come across.

The goal-directed perspective:

Cooper, 1999: The Inmates Are Running the Asylum - the first book to mention the concept of personas.

Cooper, 2007: About Face 3.0: The Essentials of Interaction Design - has two chapters on personas and scenarios.

Goodwin, 2009: Designing for the Digital Age: How to Create Human-Centered Products and Services. - gives an overview of goal-directed design including personas.

The role-based perspective

Pruitt and Adlin, 2006: The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind Throughout Product Design - a thorough introduction to all steps in personas and scenario construction.

The engaging perspective

Nielsen, 2004: Engaging Personas and Narrative Scenarios - a PhD dissertation, rather heavy on theory.

Nielsen, 2011: Persona: Brugerfokuseret design. - introduces the 10 steps, step by step. (in Danish).

Nielsen, 2012: Personas - User Focused Design. Human-Computer Interaction. Springer. - introduces the 10 steps, step by step.

Web-based design:

*Mulder and Yaar 2006: The User Is Always Right: A Practical Guide to Creating and Using Personas for the Web. *- focuses solely on web

Formal