A Short History of Neoliberalism (And How We Can Fix It)

by Jason Hickel

維吉尼亞大學人類學博士,主要研究領域為民主、暴力、全球化及非洲發展,現職為倫敦政經學院(LSE)人類學系研究員

譯者:吳奕辰(倫敦大學發展研究碩士生)

----------------------------------------------------------

身為大學老師,我經常發現我的學生將今日主流的經濟意識形態(也就是新自由主義)當作理所當然的、自然的、不可避免的。這並不意外,因為他們許多人都生於獨尊新自由主義的1990年代。在1980年代,柴契爾夫人(Margaret Thatcher)還需要說服人們除了新自由主義之外別無選擇。但今日這個假設已經是現成的、如水一般自然、是每日生活的用品。然而,這並不一直都是如此的。新自由主義有其獨特歷史,而認識其歷史是克服其霸權的解藥,這段歷史說明了今日的秩序並非自然的、亦非不可避免的;相反的,這是新的、來自某些地方的、且由特定的人群為了特定的利益而設計。

構成當今基本政策的標準經濟意識形態,在二十世紀大部分的時間裡會是被視為荒謬可笑的。類似的政策曾經被嘗試過,但造成災難性後果,而大部分經濟學家們轉而擁抱凱因斯主義,或其他形式的社會民主。如同Susan George所述:「市場應作為主要社會和政治決策、國家應該自願放棄其在經濟中的角色、企業應該被賦予完全自由、工會應該被遏止、公民的社會保險應該減少……這些想法完全背離了那段時間的主流精神。」

那麼事情是怎麼變化的?新自由主義來自何處?以下我將描繪一個簡要的歷史軌跡,告訴我們今日的運作方式是怎麼來的。我將說明新自由主義政策是西方與全球的經濟成長衰退以及社會不公急遽升高的直接因素。最後我將提出一些解決這些問題的建議。

西方脈絡下的新自由主義

故事從1930年代的大恐慌開始。大恐慌是經濟學家們所謂「過度生產危機(crisis of over-production)」產生的結果。資本主義透過增加生產和減少薪資來不斷擴張,但是這造成嚴重的不均,逐漸侵蝕人們的消費力,並且造成貨物供過於求,沒有市場出路。為了解決危機並且避免其在未來再度發生,當時的經濟學家們(以凱因斯(John Maynard Keynes)為主)建議國家應該要介入並管制資本主義。他們認為,藉由降低失業率、提高薪資、增加消費者對物品的需求,國家可以確保持續的經濟成長和社會福祉。這是資本和勞動力之間的階級妥協,防止了未來可能的不穩定。

這樣的經濟模型被稱為「鑲嵌式自由主義(embedded liberalism)」,他是資本主義的一種,鑲嵌在社會中、被政治考量所制約、致力於社會福利。他試圖創造出一批溫順而有生產力的中產勞動力,他們會有能力消費大量生產的基礎商品。這些原則被廣泛運用在二戰之後的美歐。決策者們相信他們可以將凱因斯主義的原則用來確保世界的經濟穩定和社會福祉,進而避免另一場世界大戰。他們發展出「布雷頓森林體系(Bretton Woods Institutions)」(隨後成為世界銀行、國際貨幣基金組織(IMF)、世界貿易組織(WTO)),試圖解決收支平衡的問題,並且促進戰後歐洲的重建與發展。

鑲嵌式自由主義在1950和60年代達成了高度的經濟成長,大部分發生在工業化的西方,但許多後殖民國家也得到成長。然而到了1970年代初期,鑲嵌式自由主義面臨了「停滯性通貨膨脹(stagflation)」,一種高度通貨膨脹和經濟停滯的結合。在美歐地區,通貨率從1965年的3%竄升到1975年的12%。經濟學家們在當時激烈爭辯停滯性通膨的原因。進步派學者例如克魯曼(Paul Krugman)指出兩點。首先是越戰的高額花費使美國的收支出現二十世紀首次的赤字,這使得國際投資者感到擔憂,進而拋售美元,導致通貨膨脹。尼克森加劇了通膨,為了盡快支付戰爭不斷製造的花費,他在1971年將美元與黃金脫鉤。如此一來金價一飛衝天,而美元則跌落深淵。其次,1973年的石油危機造成物價升高,拉漫了生產和經濟的成長。但是,保守派學者則反對這些解釋。他們認為停滯性通膨是繁重的富人稅和過多的經濟管制造成的。他們認為鑲嵌式自由主義已經走入死胡同,該是廢除他的時候了。

此時,保守派得到富人的支持。大衛哈維(David Harvey)認為[1],此時的富人企圖重建他們的階級在鑲嵌式自由主義中失去的權力。在戰後的美國,前1%收入者佔全國總收入從16%下降到8%。不過這並沒有造成傷害,因為經濟仍在成長,使得他們能在快速長大的果實中持續取得利潤。然而當成長停頓且通膨在1970年代爆炸,造成他們的財富開始嚴重瓦解。於是,他們除了尋求回復停滯性通膨對他們的財富所造成的影響,還要將危機當作是瓦解鑲嵌式自由主義的藉口。

他們在「沃爾克震撼(Volcker Shock)」得到解決方案。保羅沃爾克(Paul Volcher)在1979年被卡特總統任命為美國聯邦準備系統主席。在芝加哥學派經濟學家們(如Milton Friedman等)的建議下,沃爾克認為唯有藉由提升利率來壓住通膨才能解決危機。作法是箝制貨幣供給、增強儲蓄,進而增加幣值。當雷根總統於1981年就職,他再次任命沃爾克,持續推升利率,從低個位數一路上升到20%。這造成大規模衰退,引發超過10%的失業率,以及勞工組織能量的瓦解(勞工組織在鑲嵌式自由主義中是平衡資本家造成大恐慌的關鍵)。沃爾克震撼對勞工階級造成災難性影響,但是他解決了通貨膨脹。

如果貨幣緊縮政策是新自由主義在1980s年代初期誕生時的第一個元素,那麼第二個就是「供給端的經濟(supply-side economics)」。雷根想要給富人更多錢來促進經濟成長。其背後假設是,他們將會投資以及升生產能量,創造更多財富,接著逐漸「涓滴(trickle down)」到社會全體(但我們隨後將發現,這實際上並沒有發生)。最後,他將頂層的邊際稅率(marginal tax rate)從70%削減到28%,並且減少最大資本利得稅(capital gains tax)到20%,這是大恐慌以來的最低。同時,雷根也提高了勞動階級的工資稅(payroll tax),達成了共和黨單一稅(flat tax)的目標。雷根經濟計劃第三個是要素是金融部門的去管制化。因為沃爾克拒絕支持這項政策,雷根在1987年任命葛林斯潘(Alan Greenspan)取代之。葛林斯潘(貨幣主義者,推動減稅和社會保險私有化)被共和黨和民主黨持續任命直到2006年。他所推動的去管制化最終造成2008年的全球金融危機,導致上百萬人失去家園。[2]

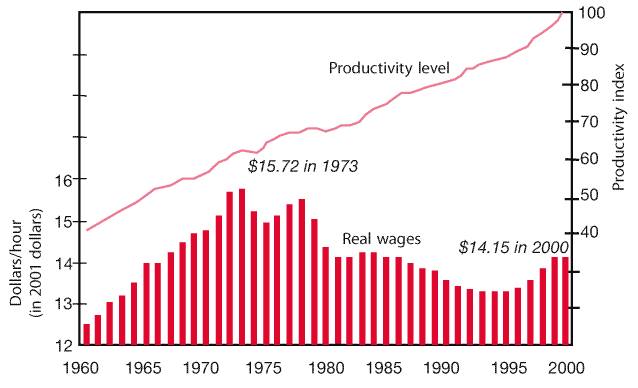

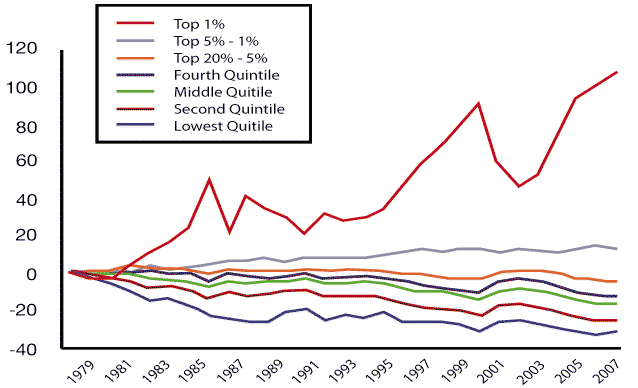

綜觀以上,這些政策(同時也在英國由柴契爾夫人執行,並且實施更強烈的私有化)導致美國的社會不均達到前所未有的頂峰。圖一顯示生產力持續穩定上升,而在1973年沃爾加震撼後薪資大跌,剩餘價值有效地從工作人口轉移到資本掌握者手中。在此潮流的背後,CEO的薪水在1990年代增加400%,工作人口薪水增加少於5%,聯邦最低薪資減少超過9%。[3] 圖二顯示最高1%收入族群占全國總收入在1980年代從8%增倍為18%(同樣的事也發生在英國,從6.5%上升到13%),這是十九世紀末鍍金時代(Gild Age)以來從未出現過的水準。普查資料顯示,美國前5%的家戶所得從1980年起增加到72.7%,而中等收入家戶則停滯,後四分之一家戶收入下降到7.4%。[4]

圖一、攻擊勞工:美國1960-2000年的實際薪資和生產力 Source: R. Pollin, Contours of Descent (New York, Verso, 2005).

圖一、攻擊勞工:美國1960-2000年的實際薪資和生產力 Source: R. Pollin, Contours of Descent (New York, Verso, 2005).

圖二、1979-2008全美收入分配 Source: Mother Jones magazine, based on US Census data

圖二、1979-2008全國收入分配 Source: Mother Jones magazine, based on US Census data

最後,關於「涓滴效應」;套用劍橋經濟學家張夏准的描述:「使富人更富有並不會使其他人也一起富有」,也不會刺激經濟成長,而這是供給端經濟學的基礎。實際上,事與願違:從新自由主義誕生以來,工業化國家的人均成長率已經從3.2%下降到2.1%。[5] 數據顯示,在推動經濟發展這部分,新自由主義徹底失敗了,但是他卻機靈地成為富有的精英重建權力的工具。

如果新自由主義政策對大部分社會是如此地破壞性,政治決策者們又為何要採行?部分原因是勞工組織在沃爾加震撼之後的瓦解。工會被妖魔化為官僚且封閉的,而左派也在蘇聯解體之後試圖和社會主義切割,美式風格的消費主義也在此時興起成為主流。企業在美國政治系統裡頭的遊說造成的影響力大增,以及華爾街資助的經濟學各學派最近爆發的利益衝突也是原因之一。但最重要的或許是在意識形態層次上。新自由主義成功地將自己行銷為典型的美國價值之一,也就是「個人自由(individual liberty)」。[6] 保守派智庫,例如朝聖山學社(Mont Pelerin Society)、美國傳統基金會(the Heritage Foundation)、商業圓桌會議(Business Roundtable)等,在過去40年致力於宣揚個人自由(liberty)唯有透過市場自由(freedom)才能達成。對他們來說,任何形式的國家介入都容易導致專制主義。這樣的立場在海耶克(Frederich Von Hayek)和傅利曼(Milton Friedman)獲得瑞典銀行紀念諾貝爾經濟學獎之後得到廣泛認同與信任。

國際層次的新自由主義

當美英等西方國家的經濟經歷了新自由主義,他們也積極地(且經常是暴力地)強迫後殖民世界採行,甚至是用極端的措施。

國際層次的新自由主義起源於1973年,為了回應當年OPEC的石油禁運,美國威脅將軍事介入阿拉伯國家,除非他們同意將油元(petrodollars)透過華爾街的投資銀行來流通。他們做到了。華爾街的銀行接著必須設法運用這些現金。此時國內經濟正在停滯,他們決定以高利率貸款的形式投資到海外,此時發展中國家正需要資金來弭平油價高漲造成的創傷,況且此時他們也正經歷高通膨。銀行認為這筆投資沒有風險,因為他們假設國家政府不太可能欠錢不還。

他們錯了。由於貸款是美元,他們和美國的利率波動連了起來。當沃爾加震撼在1980年代初期催高了利率,脆弱的發展中國家(從墨西哥開始)陷入債務泥淖,造成今日所謂的「第三世界債務危機(third world debt crisis)」。債務危機幾乎要摧毀了華爾街銀行,造成國際金融體系的瓦解。為了避免危機擴大,美國介入並確保墨西哥以及其他國家能夠還債。他們重新設計了IMF。在過去,IMF使用自身的經費協助發展中國家處理收支平衡問題;但今日,美國將使用IMF來確保第三世界國家能夠清還私人投資銀行的債務。依照哈維的說法,與此同時(1982年起),布雷頓森林體系系統性地清除了凱因斯學派的影響力,成為新自由主義意識形態的喉舌。

計畫是這樣進行的:IMF提供方案解決發展中國家的債務,但條件是他們要同意進行一系列的「結構調整方案(structural adjustment programs, SAPs)」。結構調整方案推動劇烈的市場去管制化,認為這將自動提升經濟效率、增加經濟成長,最後達成債務清償。他們藉由削減政府補貼(如食物、健康照護、交通運輸);公部門私有化;減少勞工、資源使用、人口等管制;以及移除貿易壁壘以創造「投資機會」和打開新的消費市場。他們也試圖維持低通膨,這樣第三世界對IMF的債務才不會減少,縱使這打擊了政府們推動成長的能力。這其中許多政策是為推動多國企業的利益而量身打造的,使這些企業有更多自由購買公共資產、投標政府契約、將利潤帶回國內等等。

同樣的新自由主義信條也透過世界銀行被推廣到發展中國家。世界銀行將發展計畫的貸款和許多經濟的附加條件(conditionalities)掛勾,強制推動市場自由化(特別是在1980年代)。換句話說,IMF和世界銀行將債務作為操縱其他主權國家經濟的槓桿。世界貿易組織(以及各式各樣的雙邊自由貿易協定,例如北美自由貿易協定)也藉由要求發展中國家撤除貿易壁壘換取進入西方國家市場來推動新自由主義,而這破壞了窮國的地方產業。這些組織沒有一個是民主的。IMF和世界銀行的投票權,如同企業一般,是根據各國的財務所有權來分配。主要決策需要85%才能通過,美國在兩者握有大約17%的票,意味著實質上的否決權。在世貿組織,市場大小決定了談判權力,於是富國幾乎能夠遂行其志。若窮國選擇不服從這些傷害他們經濟的貿易規則,富國能夠用制裁來報復。

新自由主義在全球化階段的最終影響是廣泛的「逐底競爭(race-to-the-bottom)」:由於多國企業能夠在全球中漫遊找尋「最佳的」投資環境,發展中國家必須相互競爭提供最廉價的勞力和資源,甚至出現免稅天堂和外資自由輸入。這對西方(以及今日的中國)多國企業的利潤來說無異是美麗新世界。但在如此之下,新自由主義的結構調整方案不再是原本該做的幫助窮國,而是摧毀窮國。在1980年代以前,發展中國家人均成長率超過3%。但是在新自由主義時代,成長率減半,只剩1.7%。[7] 撒哈拉以南非洲也展現出同樣的下墜趨勢。從1960到70年代,人均收入成長率1.6%。但是當新自由主義療方從1979年塞內加爾開始被強制在大陸上執行後,人均收入開始下降為0.7%。非洲國家平均GNP在結構調整的新自由主義年代萎縮了10%。[8] 結果,非洲生活在貧窮線以下的人數從1980年以來增倍。[9] 圖三顯示同樣的劇情也在拉丁美洲上演。前世銀經濟學家Easterly說明,一國拿到更多的結構調整貸款,就更有可能造成經濟崩潰。[10]

圖三、1950-2003年拉丁美洲實質人均收入指數與走向 Source: W. Easterly, The White Man's Burden (London, Penguin, 2006).

圖三、1950-2003年拉丁美洲實質人均收入指數與走向 Source: W. Easterly, The White Man's Burden (London, Penguin, 2006).

這些事情的發生我們不該感到意外。明目張膽的雙重標準在這裡頭進行:西方決策者要求發展中國家將經濟體自由化來推動成長,但在西方世界經濟發展的歷程中,他們自身做的完全不同。如劍橋經濟學家張夏准所述:今日的每一個富國都透過保護主義措施來發展自身的經濟。實際上直到今日,美國和英國還是兩個世界最侵略性的保護主義國家:他們藉由政府補貼、貿易壁壘、智慧財產權限制等措施建造自身的經濟力量──這些每樣都是新自由主義劇本嚴厲聲討的。Easterly認為,沒有徹底執行自由市場原則的非西方國家,反而發展地相當順利,包含日本、中國、印度、土耳其、以及亞洲四小龍。

關鍵在於,新自由主義選擇性地使用有利於經濟強權的自由市場原則。例如,美國決策者樂意擁抱市場自由,使企業能剝削海外廉價勞工、瓦解國內工會。但是另一方面,他們卻拒絕WTO要求他們放棄的大量農業補貼(這扭曲了第三世界的比較利益),因為這將違反國內有影響力的遊說團體的利益。2008年銀行救濟的行為也是另一個雙重標準。真正的自由市場會讓銀行為他們自己的錯誤付出代價。然而新自由主義在此時變成國家介入富人、自由市場留給窮人。的確,許多新自由主義製造出的問題可以藉由採行更公平的市場原則來解決。以農業貿易為例,窮國將因為更多的市場自由化而得利。另一個典型則是德國的系統:在所謂的「秩序自由主義(ordo-liberalism)」中,德國運用國家介入避免壟斷,並鼓勵中小企業的競爭。

在新自由主義全球化之下,世界前五分之一和後五分之一人口的收入斷層,從1980年的44:1竄升到1997年的74:1。[11] 圖四顯示了這個走向。美國發展經濟學家Lant Pritchett將其形容為「大離散(divergence, big time)」。今日,在這些政策的影響之下,地球上最富有的358人握有和全球最窮的45%人口(23億)同樣的財富。更驚人的是,世界前三大億萬富翁擁有的財富相當於最低開發國家(Lowest Developed Countries)(6億人)的總和。[12] 這些統計數據代表著大量的財富和資源從窮國轉移到富國。今日,世界最有錢的1%人口控制40%的財富,最有錢的10%人口控制85%的世界財富,而最窮的50%人口只握有1%的財富。[13]

圖四、1970-1995年富國和窮國收入的離散 Source: World Bank World Development Report 1999/2000.

圖四、1970-1995年富國和窮國收入的離散 Source: World Bank World Development Report 1999/2000.

若新自由主義政策導致更糟的經濟成長(在許多案例中是停滯或衰退),那麼富人和富國快速的財富累積就不只是來自某些地方的微量成長,而是有效地竊取窮人的財富。舉例來說,根據經濟學人(Economist)最近一篇文章,在美國,幾乎所有的金融危機重建所得都跑到了前1%的收入者手中。全球金融誠信(Global Financial Integrity)一篇新的研究也顯示,多國企業自1970起藉由價格轉怡和其他形式的逃稅,帳面上已經從非洲竊取了1.17兆美元。

另一個世界是有可能的

要脫離這段歷史的關鍵在於,新自由主義模型原本就是由特定的人群刻意設計的。也因為他是由人所創造,那麼就可以由人來解除。這不是自然的力量、這也不是不可避免的─另一個世界實際上是有可能的。

但我們要如何作呢?在美國,第一步關鍵會是修改憲法以排除企業人格地位(corporate personhood)。近期的「聯合公民訴聯邦選舉委員會案(Citizens United vs. FEC)」中,「言論自由」包含了允許企業無限制地投資政治宣傳,於是許多競選也朝此目標前進。第二步會是強化勞工的力量,以作為平衡資本力量的槓桿。這可以藉由聯邦最低薪資和通貨膨脹掛勾、通過「雇員自由選擇法案(Employee Free Choice Act)」允許工人在不受恐嚇的環境下組織工會、修正「勞資關係法(Taft-Hartley Act)」允許工會工廠(union shop)和代理工廠(agency shop)機構商店等等來達成。第三步會是藉由恢復「1933年銀行法(Glass-Steagall Act)」來重新制定金融部門管理方式。該法在1999年被廢除前,平衡了金融投機行為,並將商業和投資銀行分開。

2008年金融危機開始後,大眾對新自由主義的抗拒開始升高。不僅是危機暴露了極端去管制化的弊端,保守派政客也試圖將衰退用作樽節措施的藉口,號稱要「減少赤字」。樽節措施包含了大砍健康照護、教育、住房、糧食、以及其他社會救助計畫(與此同時,上兆的稅金被送進了私人銀行手中)。換句話說,政客們藉由更多的新自由主義來修補新自由主義下的資本主義危機。這不只發生在美國,也發生在歐洲。毫不意外的,赤裸裸的奪權已經激起了新興的社會運動,例如占領華爾街(Occupy Wall Street)、西班牙和希臘的indignados、以及英國50年來最大波的學潮和罷工。

在國際層次,最常見的減貧方式是「發展援助(development aid)」。然而40年來,開發援助並沒有達到目標。這種矛盾並不意外。這種與發展模型核心的矛盾並不意外,他們在施捨援助的同時要求經濟結構調整。經濟學家Robert Pollin指出,就算西方達到了聯合國的千禧年發展計畫,並且增加開發中國家援助到每年1050億美元(本身就不太可能達到),這總額仍遠遠比不上發展中國家從1980年代結構調整以來所失去的──每年4800億美元生產毛額。援助的荒謬性在於,他們運用如同走私一般的經濟政策創造了更多的問題。這也是形塑今日經濟的新自由主義意識形態的霸權。

解決這些實際議題的方案如下:首先,要將世銀、IMF、世貿組織等等民主化,確保發展中國家有能力捍衛自身的經濟利益。因為批評世銀而被開除的世銀前主任經濟學家Joseph Stiglitz,目前致力於完成這項計畫。第二,免除所有第三世界的債務以減少富國對窮國的經濟槓桿。第三,廢除附帶在對外援助和發展貸款之上的結構調整,承認每個國家有其獨特的需求。第四,設立與地方生活水平掛勾的國際最低薪資,以避免「逐底競爭」。第五,允許窮國運用進口壁壘、補貼、邊際財政赤字、低利率、資金轉移限制、國家投資幼稚產業等手段,重建到新自由主義年代前的成長水準。

最後,也是最重要的。我們必須重新詮釋自由(freedom)的意涵。我們要拒絕新自由主義版本的自由,例如市場去管制化這種實際上只是富有者累積和剝削的執照、少數人得利多數人受害的作法。我們必須認知到,週到的管制是可以推廣自由的,而這裡的自由代表的是免於匱乏的自由;擁有身為人基本尊嚴的自由,包含良好的教育、住房、健康照護;以及在一整天辛苦工作後能賺取足夠的薪資以支付像樣的生活的自由。自由不該是將經濟拉離民主社會的,我們必須認知到,真正的自由,是使經濟活動能幫助我們達到特定的社會福祉,且以民主、共同批准的方式來達到。

A Short History Of Neoliberalism (And How We Can Fix It)

by Jason Hickel

How did neoliberalism come to supplant Fordism and social democracy to the extent that it is now so widely accepted as part of the common-sense furniture of everyday life? And how can it be uprooted?

First published: 09 April, 2012 | Category:Corporate power, Economy, History, International, Vision/Strategy

As a university lecturer I often find that my students take today’s dominant economic ideology – namely, neoliberalism – for granted as natural and inevitable. This is not surprising given that most of them were born in the early 1990s, for neoliberalism is all that they have known. In the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher had to convince people that there was “no alternative” to neoliberalism. But today this assumption comes ready-made; it’s in the water, part of the common-sense furniture of everyday life, and generally accepted as given by the Right and Left alike. It has not always been this way, however. Neoliberalism has a specific history, and knowing that history is an important antidote to its hegemony, for it shows that the present order is not natural or inevitable, but rather that it is new, that it came from somewhere, and that it was designed by particular people with particular interests.

For most of the 20th century, the basic policies that comprise today’s standard economic ideology would have been rejected as absurd. Similar policies had been tried before with disastrous effects, and most economists had moved on to embrace Keynesian thought or some form of social democracy.As Susan George has put it, “The idea that the market should be allowed to make major social and political decisions; the idea that the State should voluntarily reduce its role in the economy, or that corporations should be given total freedom, that trade unions should be curbed and citizens given less rather than more social protection – such ideas were utterly foreign to the spirit of the time.”

So how did things change? Where did neoliberalism come from? In the following paragraphs I offer a simple sketch of the historical trajectory that got us to where we are today. I demonstrate that neoliberal policy is directly responsible for declining economic growth and rapidly increasing rates of social inequality – both in the West and internationally – and I make a few suggestions for how to tackle these problems.

Neoliberalism in the Western Context

The story begins with the Great Depression in the 1930s, which was a consequence of what economists call a “crisis of overproduction.” Capitalism had been expanding by increasing productivity and decreasing wages, but this generated deep inequalities, gradually eroded people’s ability to consume, and created a glut of goods that could not find a market. To solve this crisis and prevent it recurring in the future, economists of the time – led by John Maynard Keynes – suggested that the state should get involved in regulating capitalism. They argued that by lowering unemployment, raising wages, and increasing consumer demand for goods, the state could guarantee continued economic growth and social well-being – a sort of class compromise between capital and labor that would forestall further instability.

This economic model is known as “embedded liberalism” – it was a form of capitalism that was embedded in society, constrained by political concerns, and devoted to social welfare. It sought to exchange a decent family wage for a docile, productive, middle-class workforce that would have the means to consume a mass-produced set of basic commodities. These principles were widely applied after World War II in the United States and Europe. Policymakers believed that they could use Keynesian principles to ensure economic stability and social welfare around the world, and thus prevent another world war. They developed the Bretton Woods Institutions (which would later become the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO) toward this end, in order to smooth out balance of payment problems and to foster reconstruction and development in war-torn Europe.

Embedded liberalism delivered high growth rates through the 1950s and 1960s – mostly in the industrialized West, but also in many postcolonial nations. By the early 1970s, however, embedded liberalism was beginning to face a crisis of “stagflation”, which means a combination of high inflation and economic stagnation. In the US and Europe, inflation rates soared from about 3% in 1965 to about 12% ten years later. Economists debate the reasons for stagflation during this period. Progressive scholars such as Paul Krugman point to two factors. First, the high cost of the Vietnam War left the US with a balance-of-payments deficit – the first of the 20th century – to the point where worried international investors began to offload their dollars, which set inflation rates rising. Nixon exacerbated inflation when, scrambling to pay for the spiraling costs of the war, he unpegged the dollar from the gold standard in 1971: the price of gold skyrocketed while the value of the dollar plummeted. Second, the oil crisis of 1973 drove prices up and caused production and economic growth to slow down, leading to stagnation. But conservative scholars reject these reasons. Instead, they hold to a narrative that sees stagflation as a consequence of onerous taxes on the wealthy and too much economic regulation, claiming that it represented the inevitable endpoint of embedded liberalism and justified scrapping the whole system.

At the time, the latter argument held a great deal of appeal for the wealthy, who – according to David Harvey[1] – were looking for a way to restore their class power in the wake of embedded liberalism. In the US, the share of national income that went to the top 1% of earners fell from 16% to 8% during the post-war decades. This didn’t hurt them a great deal so long as economic growth remained strong, since they were getting a still-large share of a fast-growing pie. But when growth stalled and inflation exploded in the 1970s, their wealth began to collapse in a much more serious way. In response, they sought not only to reverse the effects of stagflation on their income, but also to leverage the crisis as an excuse to dismantle embedded liberalism itself.

They got their solution in the form of the “Volcker Shock.” Paul Volcker became the chairman of the US Federal Reserve in 1979, appointed by President Carter. Following the recommendations of Chicago School economists like Milton Friedman, Volcker argued that the only way to halt the crisis was to quell inflation by raising interest rates. The idea was to clamp down on the supply of money, incentivize savings, and thus increase the value of currency. When Reagan took office in 1981, he reappointed Volcker to continue to jack interest rates up from the low single digits to as high as 20%. This caused a massive recession, led to unemployment rates of over 10%, and consequently decimated the power of organized labor, which – under embedded liberalism – had been the crucial counterbalance to the capitalist excess that had lead to the Great Depression. The Volcker Shock had devastating effects on the working class; but it cured inflation.

If tight monetarist policy (i.e., targeting low inflation) was the first component of neoliberalism to be put in place in the early 1980s, the second was supply-side economics. Reagan wanted to give more money to the already-rich as a way of stimulating economic growth, the assumption being that they would invest it in productive capacity and create a windfall that would gradually “trickle down” to the rest of society (which didn’t work, as we will see). Toward this end, he cut the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 28%, and reduced the maximum capital gains tax to 20%, the lowest since the Great Depression. The lesser-known correlate of these cuts is that Reagan also raised payroll taxes on the working class, moving toward the Republican goal of an across-the-board “flat tax”. A third component of Reagan’s economic plan was to deregulate the financial sector. Because Volcker refused to support this policy, Reagan appointed Alan Greenspan to take his place in 1987. Greenspan – a monetarist who promoted tax cuts and the privatization of Social Security – was reappointed by a succession of both Republican andDemocratic presidents until 2006. The deregulations he pushed eventually precipitated the global financial crisis of 2008, during which millions of people lost their homes to foreclosure.[2]

Together, these policies (which were mirrored by Margaret Thatcher in Britain during exactly the same period, in addition to rampant privatization) drove social inequality in the United States up at an unprecedented rate, as the following graphs illustrate. Graph 1 shows how productivity continued to increase steadily during this period while wages plummeted after the Volcker Shock in 1973, effectively shifting an increasing proportion of surplus value from workers to the owners of capital. Further illustrating this trend, CEO salaries increased by an average of 400% during the 1990s while workers’ wages increased by less than 5% and the federal minimum wage decreased by more than 9%.[3]Graph 2 shows how the share of national income captured by the top strata of society has increased at an alarming rate: the portion going to the top 1% has more than doubled since 1980 from 8% to 18% (the same is true of Britain, with a jump from 6.5% to 13% during this period), restoring levels not seen since the Gilded Age. According to Census data, the top 5% of American households have seen their incomes increase by 72.7% since 1980, while median household incomes have stagnated and the bottom quintile have seen their incomes fall by 7.4%.[4]

Figure 1. The attack on labour: real wages and productivity in the US, 1960-2000

Source: R. Pollin, Contours of Descent (New York, Verso, 2005).

Figure 2. Share of national income, 1979-2008

Source: Mother Jones magazine, based on US Census data

So much for the trickle-down effect; as Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang has so aptly put it, “Making rich people richer doesn’t make the rest of us richer.” Nor does it stimulate economic growth, which is the sole justification for supply-side economics. In fact, quite the opposite is true: since the onset of neoliberalism, the industrialized world has seen average per capita growth rates fall from 3.2% to 2.1%.[5]As these numbers show, neoliberalism has completely failed as a tool for economic development, but it has worked brilliantly as a tool for restoring power to the wealthy elite.

If neoliberal policy has been so destructive to most of society, how have politicians managed to pass it off? Part of it has to do with the decimation of organized labor after the Volcker Shock, the demonization of unions as “stifling” and “bureaucratic,” attempts by the Left to distance itself from socialism after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the rise of the “consumer” as the key figure of American citizenship. We might also point to the increasing influence of corporate lobbying in the U.S. political system, and the recently exposed conflicts of interest among academic economists bankrolled by Wall Street. But perhaps most importantly, on an ideological level, neoliberalism has been successfully marketed under the quintessential American value of “individual liberty.”[6]Conservative think tanks like the Mont Pelerin Society, the Heritage Foundation, and the Business Roundtable have devoted the past forty years to peddling the idea that individual liberty can only be properly achieved through market “freedom”. For them, any form of state intervention is liable to lead to totalitarianism. This position was given credence when the two icons of neoliberal theory – Frederich Von Hayek and Milton Friedman – each won the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in the 1970s, an award commonly referred to as the Nobel Prize in Economics even though it is granted by Swedish bankers instead of the Nobel Foundation.

Neoliberalism on the International Scene

While Western countries like the United States and Britain have experimented with neoliberalism in their own economies, they have also aggressively – and often violently – forced it on the postcolonial world, and in even more extreme measures.

The history of neoliberalism on the international scene begins in 1973. Responding to the OPEC oil embargo that year, the US threatened military action against the Arab states unless they agreed to circulate their excess petrodollars through Wall Street investment banks, which they did. The banks then had to figure out what to do with all of this cash and, since the domestic economy was stagnating, they decided to spend it abroad in the form of high-interest loans to developing countries that needed funds to ease the trauma of rising oil prices, particularly given the high inflation rates of the time. The banks thought this was a safe investment because they assumed that governments would be very unlikely to default.

They were wrong. Since the loans were made in US dollars, they were linked to fluctuations in US interest rates. When the Volcker Shock hit in the early 1980s and interest rates skyrocketed, vulnerable developing countries – beginning with Mexico – slid to the edge of default, setting off what is now known as the “third world debt crisis”. The debt crisis looked set to destroy Wall Street banks and thus undermine the entire international financial system. In order to prevent such a crisis, the United States stepped in to make sure that Mexico and other countries could repay their loans. They did this by repurposing the IMF. In the past, the IMF had used its own money to assist countries in addressing balance of payments problems, but now the United States was going to use the IMF to ensure that third world countries would repay their loans to private investment banks. According to David Harvey, during this same period – beginning in 1982 – the Bretton Woods institutions were systematically “purged” of Keynesian influences and became mouthpieces of neoliberal ideology.

This is how the plan was supposed to work: the IMF offered to roll over the debts of developing countries on the condition that they would agree to a series of “structural adjustment programs”. Structural adjustment programs promote radical market deregulation on the assumption that this will automatically enhance economic efficiency, increase economic growth, and thus enable debt repayment. They do this by cutting government subsidies for things like food, healthcare, and transportation, by privatizing the public sector, by curbing regulations on labor, resource use, and pollution, and by cutting trade tariffs in order to create “investment opportunities” and open new consumer markets. They also aim to keep inflation low so that the value of third-world debt to the IMF does not diminish, even though this reduces governments' ability to spur growth. Many of these policies are specifically designed to promote the interests of multinational corporations, which are often given the freedom to buy up public assets, bid on government contracts, and repatriate profits at will.

These same neoliberal principles are pushed on developing countries through the World Bank, which gives loans for development projects that come attached with economic “conditionalities” that entail forced market liberalization (this was particularly true during the 1980s). In other words, the IMF and World Bank leverage debt as a tool for manipulating the economies of sovereign states. The World Trade Organization – along with various bilateral Free Trade Agreements, such as NAFTA – also promotes neoliberalism by granting developing countries access to Western markets only in exchange for tariff reductions, which have the effect of undermining local industry in poor countries. None of these institutions are democratic. Voting power in the IMF and World Bank is apportioned according to each nation’s share of financial ownership, just like in corporations. Major decisions require 85% of the vote, and the United States, which holds about 17% of the shares in both corporations, wields de facto veto power. At the WTO, market size determines bargaining power, so rich countries almost always get their way. If poor countries choose to disobey trade rules that hurt their economies, rich countries can retaliate with crushing sanctions.

The ultimate effect of this neoliberal phase of globalization has been a widespread race-to-the-bottom: since multinational corporations can rove the globe in search of the “best” investment conditions, developing countries have to compete with one another to offer the cheapest labor and resources, often to the point of granting extended tax holidays and free inputs to foreign investors. This has been fantastic for the profits of Western (and now Chinese) multinational corporations. But instead of helping poor countries, as they were supposedly designed to do, neoliberal structural adjustment policies have basically destroyed them. Prior to the 1980s, developing countries enjoyed a per capita growth rate of more than 3%. But during the neoliberal era growth rates were cut in half, plunging to 1.7%.[7]Sub-Saharan Africa illustrates this downward trend well. During the 1960s and 70s, per capita income grew at a modest rate of 1.6%. But when neoliberal therapy was forcibly applied to the continent, beginning with Senegal in 1979, per capita income began to fall at a rate of 0.7% per year. The GNP of the average African country shrank by around 10% during the neoliberal period of structural adjustment.[8] As a result of this, the number of Africans living in basic poverty has more than doubled since 1980.[9]Graph 3 illustrates how the same thing has happened in Latin America. Former World Bank economist William Easterly has shown that the more structural adjustment loans a country receives, the more likely its economy is to collapse.[10]

Figure 3. Per capita income index in Latin America - actual and trend 1950-2003

Source: W. Easterly, The White Man's Burden (London, Penguin, 2006).

We shouldn’t be surprised that this has happened. There is a flagrant double standard at play here: Western policymakers have been telling developing countries that they have to liberalize their economies in order to grow, but that’s exactly what the West did not do during its own period of economic consolidation. As Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang has shown, every one of today’s rich countries developed their economies through protectionist measures. In fact, until recently, the United States and Britain were the two most aggressively protectionist countries in the world: they built their economic power using government subsidies, trade tariffs, restricted patents – everything that the neoliberal playbook denounces today. William Easterly notes that the non-Western countries that did notimplement across-the-board free market principles managed to develop reasonably well, including Japan, China, India, Turkey, and the East Asian “Tigers”.

The key point to be gleaned here is that neoliberalism is a selective use of free market principles in favor of powerful economic actors. For instance, US policymakers gladly embrace market freedom if it allows corporations to exploit cheap labor abroad and undermine domestic unions. But on the other hand they refuse to heed the WTO’s demands that they abolish their massive agricultural subsidies (which distort the competitive advantage of third world countries), because that would run against the interests of a powerful corporate lobby. The 2008 bank bailouts provide another prime example of this double standard. A true free market would have left the banks to pay for their own mistakes. Neoliberalism, however, often means state intervention for the rich and free markets for the poor. Indeed, many of the problems produced by neoliberalism could be mitigated by a more equitable application of market principles. In the case of the agriculture trade, for instance, poor countries would benefit hugely from more market liberalization. Another good example is Germany’s system. Working on a theory known as ordoliberalism, Germany uses state intervention to prevent monopolies and encourage competition among small and medium-sized businesses.

As a result of neoliberal globalization, the income gap between the fifth of the world’s people living in the richest countries and the fifth in the poorest has widened significantly, moving from 44:1 in 1980 to 74:1 in 1997.[11] Graph 4 illustrates this trend, which analyst Lant Pritchett has aptly described as “divergence, big time”. Today, as a consequence of these policies, the richest 358 people on earth have the same wealth as the poorest 45% of the world’s population, or 2.3 billion people. Even more shocking, the top 3 billionaires have the same wealth as all of the Lowest Developed Countries put together, or 600 million people.[12]These statistics flag a massive transfer of wealth and resources from poor countries to rich countries, and from poor individuals to rich individuals. Today, the wealthiest 1% of the world’s population controls 40% of the world’s wealth, the wealthiest 10% control 85% of the world’s wealth, and the bottom 50% control a mere 1% of the world’s wealth.[13]

Figure 4. Diverging incomes of rich and poor countries 1970-1995

Source: World Bank World Development Report 1999/2000.

If neoliberal policy has led to worse (and in many cases stagnant or declining) economic growth rates, then the rapid accumulation of wealth by rich people and rich countries has happened not only by appropriating what little growth does happen, but effectively by stealing it from poorer ones. For example, according to a recent article in the Economist, almost all of the gains from the post-crisis recovery in the United States have accrued to the top 1% of earners. Or consider the new study by Global Financial Integrity that shows how multinational corporations have literally stolen as much as $1.17 trillion from Africa alone since 1970 through transfer pricing and other forms of tax evasion.

Another World is Possible

The key point to take away from this history is that the neoliberal model was made – intentionally – by specific people. And because it was made by people, then it can be undone by people. It is not a force of nature, and it is not inevitable; another world is in fact possible.

But how do we get there? In the United States, a first crucial step would be to amend the Constitution so as to preclude the possibility of corporate personhood. Following the recent Citizens United vs. FEC ruling, which allows corporations to spend unlimited amounts of money on political advertising as an exercise of “free speech”, a number of campaigns have made headway toward this goal. A second step would be to strengthen the power of labor to act as a counterbalance against the excess power of capital. This could be done by keeping the federal minimum wage pegged to inflation, by passing the Employee Free Choice Act with a “card-check” provision that would allow workers to form unions without fear of employer intimidation, and by amending the Taft-Hartley Act to allow union shops and agency shops. A third step would be to re-regulate the financial sector by reinstating the Glass-Steagall Act, which – until its repeal in 1999 – moderated financial speculation and separated commercial from investment banking.

Popular resistance against neoliberalism has mounted since the financial crisis of 2008. Not only did the crisis expose the flaws of extreme deregulation, but conservative policymakers have sought to leverage the recession to justify unprecedented austerity measures in the name “deficit reduction”, including deep cuts to healthcare, education, affordable housing, food stamps, and other social programs (while funnelling trillions of taxpayer dollars to private banks). In other words, policymakers hope to fix the crisis of neoliberal capitalism by prescribing yet more neoliberalism. This is true not only in the United States but across Europe as well. Not surprisingly, this naked power grab has spurred the rise of new social movements like Occupy Wall Street, the “indignados” in Spain and Greece, and in Britain the biggest spate of student protests and labor strikes for over fifty years.

On the international scene, the most common solution to the poverty crisis has been “development aid”, which – after some forty years – has failed to make a meaningful impact. This is hardly surprising given the contradiction at the heart of the development model, which doles out aid at the same time as it mandates economic structural adjustments. As economist Robert Pollin has pointed out, even if the West met the recommendations of the UN Millennium Development Project and increased aid to developing countries to $105 billion per year (an improbable wish in the first place), this sum would still pale in comparison to how much developing countries have lost as a result of structural adjustment since the 1980s, which amounts to roughly $480 billion per year in potential GDP. Again, the absurdity of aid is that it usually gets used as a way of smuggling in the exact same economic policies that created the problem in the first place. Such is the hegemony of neoliberal ideology in today’s economics.

Solutions that address the actual issues at stake might include the following: First, democratize the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO to ensure that developing countries have the capacity to defend their economic interests. Joseph Stiglitz, who was fired from his post as Chief Economist of the World Bank for his critique of these institutions, has devoted his career to developing proposals toward this end. Second, forgive all third world debt – the rallying cry of the alter-globalization movement – so as to reduce the leverage that rich countries have over the economies of poor countries. Third, get rid of blanket structural adjustment conditions associated with foreign aid and development loans, recognizing that each country has unique needs. Fourth, instate an international minimum wage pegged to local costs of living as a way of putting a floor on the “race to the bottom.” Fifth, allow poor countries to restore the levels of growth that they enjoyed prior to the neoliberal period by using strategic measures such as import tariffs, subsidies, marginal fiscal deficits, low interest rates, restrictions on transfer pricing, and state investment in infant industries.

Finally, perhaps most importantly, we need to reclaim the idea of freedom. We have to reject the neoliberal version of freedom as market deregulation, which is really just license for the rich to accumulate and exploit, and license for the few to gain at the expense of the many. We have to assert that thoughtful regulation can in fact promote freedom, if by freedom we mean freedom from poverty and want, freedom to have the basic human dignity afforded by good education, housing, and healthcare, and freedom to earn a decent living wage from a hard day’s work. Instead of accepting that freedom means unhinging the economy from the constraints of democratic society, we need to assert that true freedom entails harnessing the economy to help us achieve specific social goods that are democratically arrived at and collectively ratified.

This piece was revised and expanded slightly on October 22, 2012

[1] Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. London: Oxford University Press.

[2] Stiglitz, Joseph. 2010. Freefall. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

[3] Executive Excess 2006, the 13th annual CEO compensation survey from the Institute for Policy Studies and United for a Fair Economy.

[4] U.S. Census Bureau, Historical Income Tables: Families.

[5] Chang, Ha-Joon. 2007. Bad Samaritans: The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity. London: Random House. Pg. 26.

[6] Hickel, Jason and Arsalan Khan. 2012. “The Culture of Capitalism and the Crisis of Critique,” Anthropological Quarterly 85(1).

[7] Chang. 2007. Pg. 27.

[8] Chang. 2007. Pg. 28.

[9] World Bank. 2007. World Development Indicators.

[10] Easterly, William. 2007. The White Man’s Burden. Penguin Books.

[11] United National Development Programme. 1999. Human Development Report 1999: Globalization with a Human Face. New York. P. 38.

[12] Milanovic, Branko. 2002. “True World Income Distribution, 1988 and 1993.” Economic Journal, 112(476).

[13] United Nations University. 2009. 2008 Annual Report.