作者:埃里克·坎德尔,科学家。1929年11月7日出生于奥地利的维也纳,二战期间随家人移居美国,获美国国籍。1956年毕业于纽约大学,一生效力于精神病学和生理学研究领域并获得杰出贡献。因为在研究中发现了如何改变突触的效能,以及其中涉及了哪些分子机制,2000年获得了诺贝尔生理学与医学奖。

这本书是一本英文原版书,虽然很长,但是融合了解剖学、心理学、神经学的一本好书。 讲了 艺术、文学、潜意识、意识、大脑皮层的反应、精神分析、认知心理……

书的篇幅太长了 。 挑一些有趣的点:作者认为:艺术就好比心理学里的催眠一样都是反映潜意识。不同的是 一个用笔 一个用语音来引导出潜意识 。

The central challenge of science in the twenty-first century is to understand the human mind in biological terms. The possibility of meeting that challenge opened up in the late twentieth century, when cognitive psychology, the science of mind, merged with neuroscience, the science of the brain. The result was a new science of mind that has allowed us to address a range of questions about ourselves: How do we perceive, learn, and remember? What is the nature of emotion, empathy, thought,and consciousness? What are the limits of free will?

This new science of mind is important not only because it provides a deeper understanding of what makes us who we are, but also because it makes possible a meaningful series of dialogues between brain science and other areas of knowledge. Such dialogues could help us explore the mechanisms in the brain that make perception and creativity possible, whether in art, the sciences, the humanities, or everyday life. In a larger sense, this dialogue could help make science part of our common cultural experience.

Zuckerkandl told his audience that with “a drop of blood, a little bit of brain substance, you will be transported to a fairy-tale world.”

Carl von Rokitansky also contributed to brain research. In 1842, when he was only thirty-eight years old, he discovered that stress and other instinctual responses derive from the brain—specifically, from a region called the hypothalamus, a small cone-shaped structure that lies deep in the brain. Rokitansky found that infections at the base of the brain that affect the hypothalamus interfere with normal functioning of the stomach and often lead to massive bleeding in the stomach. This work was later extended by the brain surgeon Harvey Cushing, who showed that damage to the hypothalamus produces stress that can cause what we now call “stress ulcers” in the stomach. Subsequent work by other scientists showed that the hypothalamus controls the pituitary gland and the autonomic nervous system and therefore plays a central role in mediating sexual, aggressive, and defensive behavior and in controlling hunger, thirst, and other homeostatic functions.

In his classic text of 1886, Psychopathia Sexualis, with Special Regard to Contrary Sexual Feeling, Krafft-Ebing described a spectrum of sexual behavior and anticipated the importance of sexual instincts, two ideas that were later to emerge in psychoanalysis. Indeed, he outlined the importance of sexual instincts not only for normal and abnormal sexual functioning, but also for art, poetry, and other forms of creativity.

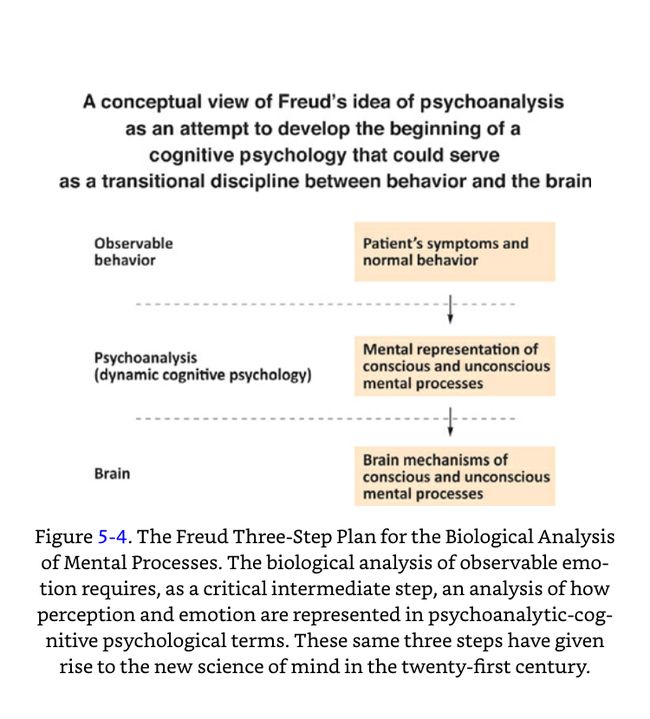

Psychoanalysis, which arose from the pioneering work with Breuer, was developed by Freud as a dynamic, introspective psychology, a precursor of modern cognitive psychology. But psychoanalysis suffered from a serious weakness: it was not empirical and was therefore not amenable to experimental testing. As a result, it is not surprising that components of Freud’s theory of mind have been proven wrong and that the assumptions of a number of other components of psychoanalytic theory have not yet been tested. Nevertheless, three of Freud’s key ideas have held up well and are now central to modern neural science. The first idea is that most of our mental life, including most of our emotional life, is unconscious at any given moment; only a small component is conscious. The second major idea is that the instincts for aggressive and for sexual strivings, like the instincts to eat and to drink, are built into the human psyche, into our genome; moreover, these instinctual drives are evident early in life. The third idea is that normal mental life and mental illness form a continuum and that mental illnesses often represent exaggerated forms of normal mental processes. As a result of these key ideas, the consensus is that Freud’s theory of mind is a monumental contribution to modern thought. Despite the obvious weakness of not being empirical, it still stands, a century later, as perhaps the most influential and coherent view of mental activity that we have.

Freud learned that a person under hypnosis remembers and expresses painful emotions but upon awakening does not remember anything he or she had just expressed—as if the conscious components of personality had not taken part in the experience. He concluded that hysterical symptoms are manifestations of emotions so painful that the patient cannot confront or express them freely, whether in the form of emotional release (such as crying or laughing), motor action, or normal social interaction. Guided by Charcot’s demonstrations and his own observations with Breuer, Freud discovered repression, a cornerstone of what would later become psychoanalytic theory. Repression is a defensive reaction, the mind’s resistance to recognizing unacceptable emotions, wishes, and patterns of action. Freud’s search for a way of overcoming repression ultimately led him to free association.

As Freud explained in his earlier, beautifully written and well-argued book On Aphasia, published in 1891: “The relationship between the chain of physiological events in the nervous system and the mental processes is probably not one of cause and effect.… The psychic is a process parallel to the physiological.”

In developing this view, Freud was employing a strategy that had been applied repeatedly in science, one based on the belief that insights into causes are most likely to emerge if a subject has first been systematically observed and described. Newton’s discovery of gravity, for example, emerged from Kepler’s astronomical observations, and Darwin’s ideas about evolution were based on the detailed classification of animals and plants by Linnaeus. Perhaps the most direct influence on Freud was the thinking of Hermann von Helmholtz. A close friend and colleague of Brücke’s and one of the most remarkable scientists of the nineteenth century, Helmholtz helped bring physiology together with physics and chemistry. In his work on visual perception, Helmholtz came to see psychology as fundamental to an understanding of brain physiology.