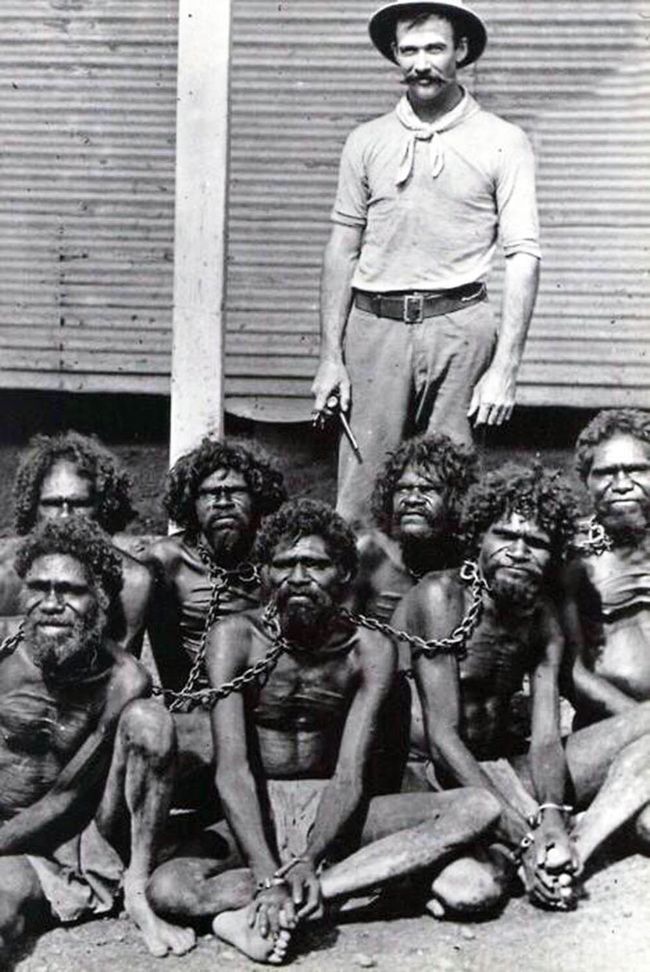

This picture is taken in the early 1900s at the Wyndham prison. Wyndam is the oldest and northernmost town in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. It was established in 1886 as a result of a gold rush at Halls Creek. However the circumstances and the story behind this picture remain unknown. The Aboriginals could have been arrested under the various local laws passed that forbid them from entering or being within a certain distance of named towns. They could also have been arrested for drinking or owning firearms which was illegal for them at various times. It’s also possible that they have been rounded up to be moved to a reserve areas which were being created at the time and that these individuals did not want to move. It could even be a staged picture for tourists/publicity reasons.

In the 19th century Australia each prisoner carried an iron chain around his neck (weighing approximately 5 pounds – 2.3 kg) in the open where temperatures usually ranged between 35 and 45 degrees Celsius. It was secured by a padlock and individual prisoners were then chained to another man. Chains of prisoners had as many as nine or ten men attached to each other. Later a new method of chaining Aboriginal prisoners was decided upon. They were to be chained from the ankles, the chain was to pass inside the leg of the prisoners trousers and supported by a heavy belt around the waist. Prisoners could then be chained in pairs and “allowed” to work outside the prison walls. There were iron rings bolted to the walls of some jail cells where prisoners were believed to be chained for chained for prison discipline.

While the Indigenous people of Australia were subject to forced labor and experienced slavery like conditions, there was no slave trading. By the time that the British effectively subdued the indigenous Australian population slave trading was already illegal in the British Empire. Moreover there was no need. While there was a manpower shortage in the early colonial settlements, the colonial government responded by making convict labor available to private individuals.

今天学习撒切尔夫人1976年1月19日的一个叫做“Britain Awake”的著名演讲:

The first duty of any Government is to safeguard its people against external aggression. To guarantee the survival of our way of life.

The question we must now ask ourselves is whether the present Government is fulfilling that duty. It is dismantling our defences at a moment when the strategic threat to Britain and her allies from an expansionist power is graver than at any moment since the end of the last war.

Military men are always warning us that the strategic balance is tilting against NATO and the west.

But the Socialists never listen.

They don't seem to realise that the submarines and missiles that the Russians are building could be destined to be used against us.

Perhaps some people in the Labour Party think we are on the same side as the Russians!

But just let's look at what the Russians are doing.

She's ruled by a dictatorship of patient, far-sighted determined men who are rapidly making their country the foremost naval and military power in the world.

They are not doing this solely for the sake of self-defence.

A huge, largely land-locked country like Russia does not need to build the most powerful navy in the world just to guard its own frontiers.

No. The Russians are bent on world dominance, and they are rapidly acquiring the means to become the most powerful imperial nation the world has seen.

The men in the Soviet politburo don't have to worry about the ebb and flow of public opinion. They put guns before butter, while we put just about everything before guns.

They know that they are a super power in only one sense—the military sense.

They are a failure in human and economic terms.

But let us make no mistake. The Russians calculate that their military strength will more than make up for their economic and social weakness. They are determined to use it in order to get what they want from us.

Last year on the eve of the Helsinki Conference, I warned that the Soviet Union is spending 20 per cent more each year than the United States on military research and development. 25 per cent more on weapons and equipment. 60 per cent more on strategic nuclear forces.

In the past ten years Russia has spent 50 per cent more than the United States on naval shipbuilding.

Some military experts believe that Russia has already achieved strategic superiority over America.

But it is the balance of conventional forces which poses the most immediate dangers for NATO.

I am going to visit our troops in Germany on Thursday. I am going at a moment when the Warsaw Pact forces—that is, the forces of Russia and her allies—in Central Europe outnumber NATOs by 150,000 men nearly 10,000 tanks and 2,600 aircraft. We cannot afford to let that gap get bigger.

Still more serious gaps have opened up elsewhere—especially in the troubled area of Southern Europe and the Mediterranean.

The rise of Russia as a world-wide naval power, threatens our oil rigs and our traditional life-lines, the sea routes.

Over the past ten years, the Russians have quadrupled their force of nuclear submarines. They are now building one nuclear submarine a month.

They are searching for new naval base facilities all over the world, while we are giving up our few remaining bases.

They have moved into the Indian Ocean. They pose a rising threat to our northern waters and, farther east to Japan's vital sea routes.

The Soviet navy is not designed for self-defence. We do not have to imagine an all-out nuclear war or even a conventional war in order to see how it could be used for political purposes.

I would be the first to welcome any evidence that the Russians are ready to enter into a genuine detente. But I am afraid that the evidence points the other way.

I warned before Helsinki of the dangers of falling for an illusory detente. Some people were sceptical at the time, but we now see that my warning was fully justified.

Has detente induced the Russians to cut back on their defence programme?

Has it dissuaded them from brazen intervention in Angola?

Has it led to any improvement in the conditions of Soviet citizens, or the subject populations of Eastern Europe?

We know the answers.

At Helsinki we endorsed the status quo in Eastern Europe. In return we had hoped for the freer movement of people and ideas across the Iron Curtain. So far we have got nothing of substance.

We are devoted, as we always have been, to the maintenance of peace.

We will welcome any initiative from the Soviet Union that would contribute to that goal.

But we must also heed the warnings of those, like Alexander Solzhenitsyn , who remind us that we have been fighting a kind of ‘Third World War’ over the entire period since 1945—and that we have been steadily losing ground.

As we look back over the battles of the past year, over the list of countries that have been lost to freedom or are imperilled by Soviet expansion can we deny that Solzhenitsyn is right?

We have seen Vietnam and all of Indochina swallowed up by Communist aggression. We have seen the Communists make an open grab for power in Portugal, our oldest ally—a sign that many of the battles in the Third World War are being fought inside Western countries.

And now the Soviet Union and its satellites are pouring money, arms and front-line troops into Angola in the hope of dragging it into the Communist bloc.

We must remember that there are no Queensbury rules in the contest that is now going on. And the Russians are playing to win.

They have one great advantage over us—the battles are being fought on our territory, not theirs.

Within a week of the Helsinki conference, Mr Zarodov , a leading Soviet ideologue, was writing in Pravda about the need for the Communist Parties of Western Europe to forget about tactical compromises with Social Democrats, and take the offensive in order to bring about proletarian revolution.

Later Mr Brezhnev made a statement in which he gave this article his personal endorsement.

If this is the line that the Soviet leadership adopts at its Party Congress next month, then we must heed their warning. It undoubtedly applies to us too.

We in Britain cannot opt out of the world.

If we cannot understand why the Russians are rapidly becoming the greatest naval and military power the world has ever seen if we cannot draw the lesson of what they tried to do in Portugal and are now trying to do in Angola then we are destined—in their words—to end up on ‘the scrap heap of history’.

We look to our alliance with American and NATO as the main guarantee of our own security and, in the world beyond Europe, the United States is still the prime champion of freedom.

But we are all aware of how the bitter experience of Vietnam has changed the public mood in America. We are also aware of the circumstances that inhibit action by an American president in an election year.

So it is more vital then ever that each and every one of us within NATO should contribute his proper share to the defence of freedom.

Britain, with her world-wide experience of diplomacy and defence, has a special role to play. We in the Conservative Party are determined that Britain should fulfil that role.

We're not harking back to some nostalgic illusion about Britain's role in the past.

We're saying—Britain has a part to play now, a part to play for the future.

The advance of Communist power threatens our whole way of life. That advance is not irreversible, providing that we take the necessary measures now. But the longer that we go on running down our means of survival, the harder it will be to catch up.

In other words: the longer Labour remains in Government, the more vulnerable this country will be. (Applause.)

What has this Government been doing with our defences?

Under the last defence review, the Government said it would cut defence spending by £4,700 million over the next nine years.

Then they said they would cut a further £110 million.

It now seems that we will see further cuts.

If there are further cuts, perhaps the [ Roy Mason ] Defence Secretary should change his title, for the sake of accuracy, to the Secretary for Insecurity.

On defence, we are now spending less per head of the population than any of our major allies. Britain spends only £90 per head on defence. West Germany spends £130, France spends £115. The United States spends £215. Even neutral Sweden spends £60 more per head than we do.

Of course, we are poorer than most of our NATO allies. This is part of the disastrous economic legacy of Socialism.

But let us be clear about one thing.

This is not a moment when anyone with the interests of this country at heart should be talking about cutting our defences.

It is a time when we urgently need to strengthen our defences.

Of course this places a burden on us. But it is one that we must be willing to bear if we want our freedom to survive.

Throughout our history, we have carried the torch for freedom. Now, as I travel the world, I find people asking again and again, "What has happened to Britain?" They want to know why we are hiding our heads in the sand, why with all our experience, we are not giving a lead.

Many people may not be aware, even now, of the full extent of the threat.

We expect our Governments to take a more far-sighted view.

To give them their due, the Government spelled out the extent of the peril in their Defence White Paper last year, But, having done so, they drew the absurd conclusion that our defence efforts should be reduced.

The Socialists, in fact, seem to regard defence as almost infinitely cuttable. They are much more cautious when it comes to cutting other types of public expenditure.

They seem to think that we can afford to go deeper into debt so that the Government can prop up a loss-making company. And waste our money on the profligate extension of nationalisation and measures such as the Community Land Act.

Apparently, we can even afford to lend money to the Russians, at a lower rate of interest that we have to pay on our own borrowings.

But we cannot afford, in Labour's view, to maintain our defences at the necessary level—not even at a time when on top of our NATO commitments, we are fighting a major internal war against terrorism in Northern Ireland, and need more troops in order to win it.

There are crises farther from home that could affect us deeply. Angola is the most immediate.

In Angola, the Soviet-backed guerrilla movement, the MPLA, is making rapid headway in its current offensive, despite the fact that it controls only a third of the population, and is supported by even less.

The MPLA is gaining ground because the Soviet Union and its satellites are pouring money, guns and front-line troops into the battle.

Six thousand Cuban regular soldiers are still there.

But it is obvious that an acceptable solution for Angola is only possible if all outside powers withdraw their military support.

You might well ask: why on earth should we think twice about what is happening in a far-away place like Angola?

There are four important reasons.

The first is that Angola occupies a vital strategic position. If the pro-Soviet faction wins, one of the immediate consequences will almost certainly be the setting up of Soviet air and naval bases on the South Atlantic.

The second reason is that the presence of Communist forces in this area will make it much more difficult to settle the Rhodesian problem and achieve an understanding between South Africa and black Africa.

The third reason is even more far-reaching.

If the Russians have their way in Angola, they may well conclude that they can repeat the performance elsewhere. Similarly, uncommitted nations would be left to conclude that NATO is a spent force and that their best policy is to pursue an accommodation with Russia.

Fourthly, what the Russians are doing in Angola is against detente.

They seem to believe that their intervention is consistent with detente.

Indeed, Izvestiya recently argued that Soviet support for the Communist MPLA is "an investment in detente"—which gives us a good idea of what they really mean by the word.

We should make it plain to the Russians that we do not believe that what they are doing in Angola is consistent with detente.

It is usually said that NATO policy ends in North Africa at the Tropic of Cancer. But the situation in Angola brings home the fact that NATOs supplylines need to be protected much further south.

In the Conservative Party we believe that our foreign policy should continue to be based on a close understanding with our traditional ally, America.

This is part of our Anglo-Saxon tradition as well as part of our NATO commitment, and it adds to our contribution to the European Community.

Our Anglo-Saxon heritage embraces the countries of the Old Commonwealth that have too often been neglected by politicians in this country, but are always close to the hearts of British people.

We believe that we should build on our traditional bonds with Australia, New Zealand and Canada, as well as on our new ties with Europe.

I am delighted to see that the Australians and the New Zealanders have concluded—as I believe that most people in this country are coming to conclude—that Socialism has failed.

In their two electoral avalanches at the end of last year, they brought back Governments committed to freedom of choice, governments that will roll back the frontiers of state intervention in the economy and will restore incentives for people to work and save.

Our congratulations go to Mr Fraser and Mr Muldoon .

I know that our countries will be able to learn from each other.

What has happened in Australasia is part of a wider reawakening to the need to provide a more positive defence of the values and traditions on which Western civilisation, and prosperity, are based.

We stand with that select body of nations that believe in democracy and social and economic freedom.

Part of Britain's world role should be to provide, through its spokesmen, a reasoned and vigorous defence of the Western concept of rights and liberties: The kind that America's Ambassador to the UN, Mr Moynihan , has recently provided in his powerfully argued speeches.

But our role reaches beyond this. We have abundant experience and expertise in this country in the art of diplomacy in its broadest sense.

It should be used, within Europe, in the efforts to achieve effective foreign policy initiatives.

Within the EEC, the interests of individual nations are not identical and our separate identities must be seen as a strength rather than a weakness.

Any steps towards closer European union must be carefully considered.

We are committed to direct elections within the Community, but the timing needs to be carefully calculated.

But new problems are looming up.

Among them is the possibility that the Communists will come to power through a coalition in Italy. This is a good reason why we should aim for closer links between those political groups in the European Parliament that reject Socialism.

We have a difficult year ahead in 1976.

I hope it will not result in a further decline of Western power and influence of the kind that we saw in 1975.

It is clear that internal violence—and above all political terrorism—will continue to pose a major challenge to all Western societies, and that it may be exploited as an instrument by the Communists.

We should seek close co-ordination between the police and security services of the Community, and of Nato, in the battle against terrorism.

The way that our own police have coped with recent terrorist incidents provides a splendid model for other forces.

The message of the Conservative Party is that Britain has an important role to play on the world stage. It is based on the remarkable qualities of the British people. Labour has neglected that role. MT apparently omitted the following passage in delivery. She noted, "If short of time go to top of page 32 (We are often told)." Pages 29–31 of the text are clipped together.

Our capacity to play a constructive role in world affairs is of course related to our economic and military strength.

Socialism has weakened us on both counts. This puts at risk not just our chance to play a useful role in the councils of the world, but the Survival of our way of life.

Caught up in the problems and hardships that Socialism has brought to Britain, we are sometimes in danger of failing to see the vast transformations taking place in the world that dwarf our own problems, great though they are.

But we have to wake up to those developments, and find the political will to respond to them.

Soviet military power will not disappear just because we refuse to look at it.

And we must assume that it is there to be used—as threat or as force—unless we maintain the necessary deterrents.

We are under no illusions about the limits of British influence. End of passage probably omitted in delivery.

We are often told how this country that once ruled a quarter of the world is today just a group of offshore islands.

Well, we in the Conservative Party believe that Britain is still great.

The decline of our relative power in the world was partly inevitable—with the rise of the super powers with their vast reserves of manpower and resources.

But it was partly avoidable too—the result of our economic decline accelerated by Socialism.

We must reverse that decline when we are returned to Government.

In the meantime, the Conservative Party has the vital task of shaking the British public out of a long sleep.

Sedatives have been prescribed by people, in and out of Government, telling us that there is no external threat to Britain, that all is sweetness and light in Moscow, and that a squadron of fighter planes or a company of marine commandos is less important than some new subsidy.

The Conservative Party must now sound the warning.

There are moments in our history when we have to make a fundamental choice.

This is one such moment—a moment when our choice will determine the life or death of our kind of society,—and the future of our children.

Let's ensure that our children will have cause to rejoice that we did not forsake their freedom.

今天学习的TED是 Julian Treasure 的《How to speak so that people want to listen》:

Julian Treasure is the chair of the Sound Agency, a firm that advises worldwide businesses -- offices, retailers, hotels -- on how to use sound. He asks us to pay attention to the sounds that surround us. How do they make us feel: productive, stressed, energized, acquisitive?

The human voice: It's the instrument we all play. It's the most powerful sound in the world, probably. It's the only one that can start a war or say "I love you." And yet many people have the experience that when they speak, people don't listen to them. And why is that? How can we speak powerfully to make change in the world?

What I'd like to suggest, there are a number of habits that we need to move away from. I've assembled for your pleasure here seven deadly sins of speaking. I'm not pretending this is an exhaustive list, but these seven, I think, are pretty large habits that we can all fall into.

First, gossip. Speaking ill of somebody who's not present. Not a nice habit, and we know perfectly well the person gossiping, five minutes later, will be gossiping about us.

Second, judging. We know people who are like this in conversation, and it's very hard to listen to somebody if you know that you're being judged and found wanting at the same time.

Third, negativity. You can fall into this. My mother, in the last years of her life, became very negative, and it's hard to listen. I remember one day, I said to her, "It's October 1 today," and she said, "I know, isn't it dreadful?"

It's hard to listen when somebody's that negative.

And another form of negativity, complaining. Well, this is the national art of the U.K. It's our national sport. We complain about the weather, sport, about politics, about everything, but actually, complaining is viral misery. It's not spreading sunshine and lightness in the world.

Excuses.

We've all met this guy. Maybe we've all been this guy. Some people have a blamethrower. They just pass it on to everybody else and don't take responsibility for their actions, and again, hard to listen to somebody who is being like that.

Penultimate, the sixth of the seven, embroidery, exaggeration. It demeans our language, actually, sometimes. For example, if I see something that really is awesome, what do I call it?

And then, of course, this exaggeration becomes lying, and we don't want to listen to people we know are lying to us.

And finally, dogmatism. The confusion of facts with opinions. When those two things get conflated, you're listening into the wind. You know, somebody is bombarding you with their opinions as if they were true. It's difficult to listen to that.

So here they are, seven deadly sins of speaking. These are things I think we need to avoid. But is there a positive way to think about this? Yes, there is. I'd like to suggest that there are four really powerful cornerstones, foundations, that we can stand on if we want our speech to be powerful and to make change in the world. Fortunately, these things spell a word. The word is "hail," and it has a great definition as well. I'm not talking about the stuff that falls from the sky and hits you on the head. I'm talking about this definition, to greet or acclaim enthusiastically, which is how I think our words will be received if we stand on these four things.

So what do they stand for? See if you can guess. The H, honesty, of course, being true in what you say, being straight and clear. The A is authenticity, just being yourself. A friend of mine described it as standing in your own truth, which I think is a lovely way to put it. The I is integrity, being your word, actually doing what you say, and being somebody people can trust. And the L is love. I don't mean romantic love, but I do mean wishing people well, for two reasons. First of all, I think absolute honesty may not be what we want. I mean, my goodness, you look ugly this morning. Perhaps that's not necessary. Tempered with love, of course, honesty is a great thing. But also, if you're really wishing somebody well, it's very hard to judge them at the same time. I'm not even sure you can do those two things simultaneously. So hail.

Also, now that's what you say, and it's like the old song, it is what you say, it's also the way that you say it. You have an amazing toolbox. This instrument is incredible, and yet this is a toolbox that very few people have ever opened. I'd like to have a little rummage in there with you now and just pull a few tools out that you might like to take away and play with, which will increase the power of your speaking.

Register, for example. Now, falsetto register may not be very useful most of the time, but there's a register in between. I'm not going to get very technical about this for any of you who are voice coaches. You can locate your voice, however. So if I talk up here in my nose, you can hear the difference. If I go down here in my throat, which is where most of us speak from most of the time. But if you want weight, you need to go down here to the chest. You hear the difference? We vote for politicians with lower voices, it's true, because we associate depth with power and with authority. That's register.

Then we have timbre. It's the way your voice feels. Again, the research shows that we prefer voices which are rich, smooth, warm, like hot chocolate. Well if that's not you, that's not the end of the world, because you can train. Go and get a voice coach. And there are amazing things you can do with breathing, with posture, and with exercises to improve the timbre of your voice.

Then prosody. I love prosody. This is the sing-song, the meta-language that we use in order to impart meaning. It's root one for meaning in conversation. People who speak all on one note are really quite hard to listen to if they don't have any prosody at all. That's where the word "monotonic" comes from, or monotonous, monotone. Also, we have repetitive prosody now coming in, where every sentence ends as if it were a question when it's actually not a question, it's a statement?

And if you repeat that one, it's actually restricting your ability to communicate through prosody, which I think is a shame, so let's try and break that habit.

Pace.

I can get very excited by saying something really quickly, or I can slow right down to emphasize, and at the end of that, of course, is our old friend silence. There's nothing wrong with a bit of silence in a talk, is there? We don't have to fill it with ums and ahs. It can be very powerful.

Of course, pitch often goes along with pace to indicate arousal, but you can do it just with pitch. Where did you leave my keys? (Higher pitch) Where did you leave my keys? So, slightly different meaning in those two deliveries.

And finally, volume. (Loud) I can get really excited by using volume. Sorry about that, if I startled anybody. Or, I can have you really pay attention by getting very quiet. Some people broadcast the whole time. Try not to do that. That's called sodcasting,

Imposing your sound on people around you carelessly and inconsiderately. Not nice.

Of course, where this all comes into play most of all is when you've got something really important to do. It might be standing on a stage like this and giving a talk to people. It might be proposing marriage, asking for a raise, a wedding speech. Whatever it is, if it's really important, you owe it to yourself to look at this toolbox and the engine that it's going to work on, and no engine works well without being warmed up. Warm up your voice.

Actually, let me show you how to do that. Would you all like to stand up for a moment? I'm going to show you the six vocal warm-up exercises that I do before every talk I ever do. Any time you're going to talk to anybody important, do these. First, arms up, deep breath in, and sigh out, ahhhhh, like that. One more time. Ahhhh, very good. Now we're going to warm up our lips, and we're going to go Ba, Ba, Ba, Ba, Ba, Ba, Ba, Ba. Very good. And now, brrrrrrrrrr, just like when you were a kid. Brrrr. Now your lips should be coming alive. We're going to do the tongue next with exaggerated la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la, la. Beautiful. You're getting really good at this. And then, roll an R. Rrrrrrr. That's like champagne for the tongue. Finally, and if I can only do one, the pros call this the siren. It's really good. It starts with "we" and goes to "aw." The "we" is high, the "aw" is low. So you go, weeeaawww, weeeaawww.

Fantastic. Give yourselves a round of applause. Take a seat, thank you.

Next time you speak, do those in advance.

Now let me just put this in context to close. This is a serious point here. This is where we are now, right? We speak not very well to people who simply aren't listening in an environment that's all about noise and bad acoustics. I have talked about that on this stage in different phases. What would the world be like if we were speaking powerfully to people who were listening consciously in environments which were actually fit for purpose? Or to make that a bit larger, what would the world be like if we were creating sound consciously and consuming sound consciously and designing all our environments consciously for sound? That would be a world that does sound beautiful, and one where understanding would be the norm, and that is an idea worth spreading.

Thank you.