CHAPTER 1

Losing Weight

Scott Carey knocked on the door of the Ellis condo unit, and Bob Ellis (everyone in Highland Acres still called him Doctor Bob, although he was five years retired) let him in. “Well, Scott, here you are. Ten on the dot. Now what can I do for you?”

Scott was a big man, six-feet-four in his stocking feet, with a bit of a belly growing in front. “I’m not sure. Probably nothing, but . . . I have a problem. I hope not a big one, but it might be.”

“One you don’t want to talk to your regular doctor about?” Ellis was seventy-four, with thinning silver hair and a small limp that didn’t slow him down much on the tennis court. Which was where he and Scott had met, and become friends. Not close friends, maybe, but friends, sure enough.

“Oh, I went,” Scott said, “and got a checkup. Which was overdue. Bloodwork, urine, prostate, the whole nine yards. Everything checked out. Cholesterol a little high, but still in the normal range. It was diabetes I was worried about. WebMD suggested that was the most likely.”

Until he knew about the clothes, that was. The thing with the clothes wasn’t on any website, medical or otherwise. It certainly had nothing to do with diabetes.

Ellis led him into the living room, where a big bay window overlooked the fourteenth green of the Castle Rock gated community where he and his wife now lived. Doctor Bob played the occasional round, but mostly stuck to tennis. It was Ellis’s wife who enjoyed golf, and Scott suspected that was the reason they were living here, when they weren’t spending winters in a similar sports-oriented development in Florida.

Ellis said, “If you’re looking for Myra, she’s at her Methodist Women’s group. I think that’s right, although it might be one of her town committees. Tomorrow she’s off to Portland for a meeting of the New England Mycological Society. That woman hops around like a hen on a hot griddle. Take off your coat, sit down, and tell me what’s on your mind.”

Although it was early October and not particularly cold, Scott was wearing a North Face parka. When he took it off and laid it beside him on the sofa, the pockets jingled.

“Would you like coffee? Tea? I think there’s a breakfast pastry, if—”

“I’m losing weight,” Scott said abruptly. “That’s what’s on my mind. It’s sort of funny, you know. I used to steer clear of the bathroom scale, because these last ten years or so, I haven’t been crazy about the news I got from it. Now I’m on it first thing every morning.”

Ellis nodded. “I see.”

No reason for him to avoid the bathroom scale, Scott thought; the man was what his grandmother would have called a stuffed string. He’d probably live another twenty years, if a wild card didn’t come out of the deck. Maybe even make the century.

“I certainly understand the scale-avoidance syndrome, saw it all the time when I was practicing. I also saw the opposite, compulsive weighing. Usually in bulimics and anorexics. You hardly look like one of those.” He leaned forward, hands clasped between his skinny thighs. “You do understand that I’m retired, don’t you? I can advise, but I can’t prescribe. And my advice will probably be for you to go back to your regular doctor, and make a full disclosure.”

Scott smiled. “I suspect my doc would want me in the hospital for tests right away, and last month I landed a big job, designing interlocking websites for a department store chain. I won’t go into details, but it’s a plum. I was very fortunate to get the gig. It’s a large step up for me, and I can do it without moving out of Castle Rock. That’s the beauty of the computer age.”

“But you can’t work if you fall ill,” Ellis said. “You’re a smart guy, Scott, and I’m sure you know that weight-loss isn’t just a marker for diabetes, it’s a marker for cancer. Among other things. How much weight are we talking about?”

“Twenty-eight pounds.” Scott looked out the window and observed white golf carts moving over green grass beneath a blue sky. As a photograph, it would have looked good on the Highland Acres website. He was sure they had one—everyone did these days, even roadside stands selling corn and apples had websites—but he hadn’t created it. He had moved on to bigger things. “So far.”

Bob Ellis grinned, showing teeth that were still his own. “That’s a fair amount, all right, but my guess is you could stand to lose it. You move very well on the tennis court for a big man, and you put in your time on the machines in the health club, but carrying too many pounds puts a strain not just on the heart but the whole kit and caboodle. As I’m sure you know. From WebMD.” He rolled his eyes at this, and Scott smiled. “What are you now?”

“Guess,” Scott said.

Bob laughed. “What do you think this is, the county fair? I’m fresh out of Kewpie dolls.”

“You were in general practice for what, thirty-five years?”

“Forty-two.”

“So don’t be modest, you’ve weighed thousands of patients thousands of times.” Scott stood up, a tall man with a big frame wearing jeans, a flannel shirt, and scuffed-up Georgia Giants. He looked more like a woodsman or a horse-wrangler than a web designer. “Guess my weight. We’ll get to my fate later.”

Doctor Bob cast the eye of a professional up and down Scott Carey’s seventy-six inches—more like seventy-eight, in the boots. He paid particular attention to the curve of belly over the belt, and the long thigh muscles built up by leg-presses and hack squats on machines Doctor Bob now avoided. “Unbutton your shirt and hold it open.”

Scott did this, revealing a gray tee with UNIVERSITY OF MAINE ATHLETIC DEPARTMENT on the front. Bob saw a broad chest, muscular, but developing those adipose deposits wiseass kids liked to call man-tits.

“I’m going to say . . .” Ellis paused, interested in the challenge now. “I’m going to say 235. Maybe 240. Which means you must have been up around 270 before you started to lose. I must say you carried it well on the tennis court. That much I wouldn’t have guessed.”

Scott remembered how happy he had been when he’d finally mustered the courage to get on the scale earlier this month. Delighted, actually. The steady rate of the weight-loss since then was worrisome, yes, but only a little. It was the clothes thing that had changed worry to fright. You didn’t need WebMD to tell you that the clothes thing was more than strange; it was fucking outré.

Outside, a golf cart trundled past. In it were two middle-aged men, one in pink pants, one in green, both overweight. Scott thought they would have done themselves some good by ditching the cart and walking their round, instead.

“Scott?” Doctor Bob said. “Are you there, or did I lose you?”

“I’m here,” Scott said. “The last time we played tennis, I did go 240. I know, because that was when I finally got on the scale. I decided the time had come to drop a few pounds. I was starting to get all out of breath by the third set. But as of this morning, I weigh 212.”

He sat down again next to his parka (which gave another jingle). Bob eyed him carefully. “You don’t look like 212 to me, Scott. Pardon me for saying, but you look quite a bit heavier than that.”

“But healthy?”

“Yes.”

“Not sick.”

“No. Not to look at you, anyway, but—”

“Have you got a scale? I bet you do. Let’s check it out.”

Doctor Bob considered him for a moment, wondering if Scott’s actual problem might be in the gray matter above his eyebrows. In his experience, it was mostly women who tended to be neurotic about their weight, but it happened with men, too. “All right, let’s do that. Follow me.”

Bob led him into a study stocked with bookshelves. There was a framed anatomy chart on one wall and a line of diplomas on another. Scott was staring at the paperweight between Ellis’s computer and his printer. Bob followed his gaze and laughed. He picked the skull up off the desk and tossed it to Scott.

“Plastic rather than bone, so don’t worry about dropping it. A gift from my eldest grandson. He’s thirteen, which I think of as the Age of Tasteless Gifts. Step over here, and let’s see what we’ve got.”

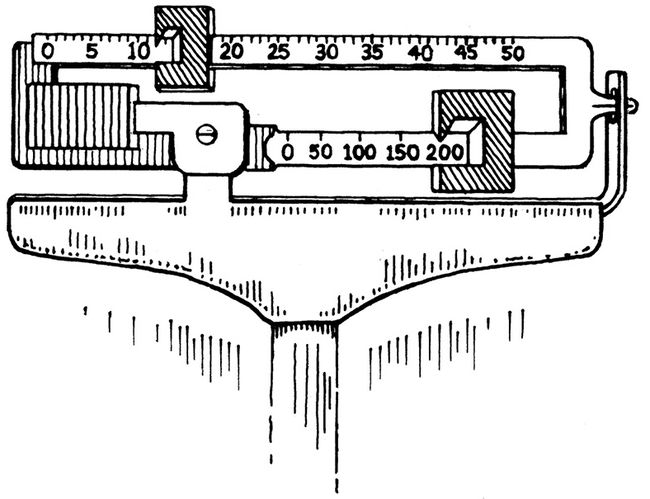

In the corner was a gantry-like scale upon which two weights, one big and one little, could be moved until the steel beam balanced. Ellis gave it a pat. “The only things I kept when I closed my office downtown were the anatomy chart on the wall and this. It’s a Seca, the finest medical scale ever made. A gift from my wife, many years ago, and believe me when I say no one ever accused her of being tasteless. Or cheap.”

“Is it accurate?”

“Let’s just say if I weighed a twenty-five-pound bag of flour on it, and the scale said it weighed twenty-four, I’d go back to Hannaford’s and demand a refund. You should take off your boots if you want something close to a true weight. And why did you bring your coat?”

“You’ll see.” Scott didn’t take off his boots but put the parka on instead, to the tune of more jingling from the pockets. Now not just fully dressed but dressed for the outside on a day much colder than this one, he stepped on the scale. “Let ’er rip.”

In order to allow for the boots and the coat, Bob ran the counterweight all the way to 250, then worked backward, first sliding the weight, then nudging it along. The needle of the balance bar remained grounded at 240, and 230, and 220, which Doctor Bob would have thought impossible. Never mind the coat and boots; Scott Carey simply looked heavier than that. He could have been off in his estimate by a few pounds, but he had weighed too many overweight men and women to be this far off.

The bar balanced at 212 pounds.

“I’ll be dipped in pitch,” Doctor Bob said. “I need to have this thing recalibrated.”

“Don’t think so,” Scott said. He stepped off the scale and put his hands in his coat pockets. From each, he took a fistful of quarters. “Been saving these in an antique chamber pot for years. By the time Nora left, it was almost full. I must have five pounds of metal in each pocket, maybe more.”

Ellis said nothing. He was speechless.

“Now do you see why I didn’t want to go to Dr. Adams?” Scott let the coins slide back into his coat pockets with another jolly jingle.

Ellis found his voice. “Let me be sure I have this right—you’re getting the same weight at home?”

“To the pound. My scale’s an Ozeri step-on, maybe not as good as this baby, but I’ve tested it and it’s accurate. Now watch this. I usually like a little bump-and-grind music when I strip, but since we’ve undressed together in the club locker room, I guess I can do without it.”

Scott took off his parka and hung it on the back of a chair. Then, balancing with first one hand and then the other on Doctor Bob’s desk, he took off his boots. Next came the flannel shirt. He unbuckled his belt, stepped out of his jeans, and stood there in his boxers, tee-shirt, and socks.

“I could shuck these as well,” he said, “but I think I’ve taken off enough to make the point. Because, see, this is what scared me. The thing about the clothes. It’s why I wanted to talk to a friend who could keep his mouth shut instead of my regular doc.” He pointed to the clothes and boots on the floor, then at the parka with its sagging pockets. “How much would you say all that stuff weighs?”

“With the coins? At least fourteen pounds. Possibly as much as eighteen. Do you want to weigh them?”

“No,” Scott said.

He got back on the scale. There was no need to move the weights. The beam balanced at 212 pounds.

* * *

Scott dressed and they went back to the living room. Doctor Bob poured them each a tiny knock of Woodford Reserve, and although it was only ten in the morning, Scott did not refuse. He took his down in a single swallow, and the whiskey lit a comforting fire in his stomach. Ellis took two delicate birdy sips, as if testing the quality, then tossed off the rest. “It’s impossible, you know,” he said as he put the empty glass on an endtable.

Scott nodded. “Another reason I didn’t want to talk to Dr. Adams.”

“Because it would be in the system,” Ellis said. “A matter of record. And yes, he’d have insisted you undergo tests in order to find out exactly what’s going on with you.”

Although he didn’t say so, Scott thought insisted was too mild. In Dr. Adams’s consulting room, the phrase that had popped into his head was taken into custody. That was when he’d decided to keep his mouth shut and talk to his retired medical friend instead.

“You look 240,” Ellis said. “Is that how you feel?”

“Not exactly. I felt a little . . . mmm . . .ploddy when I actually did weigh 240. I guess that’s not a real word, but it’s the best I can do.”

“I think it’s a good word,” Ellis said, “whether it’s in the dictionary or not.”

“It wasn’t just being overweight, although I knew I was. It was that, and age, and . . .”

“The divorce?” Ellis asked it gently, in his most Doctor Bobly way.

Scott sighed. “Sure, that too. It’s cast a shadow over my life. It’s better now, I’mbetter, but it’s still there. Can’t lie about that. Physically, though, I never felt bad, still worked out a little three times a week, never got out of breath until the third set, but just . . . you know, ploddy. Now I don’t, or at least not so much.”

“More energy.”

Scott considered, then shook his head. “Not exactly. It’s more like the energy I have goes further.”

“No lethargy? No fatigue?”

“No.”

“No loss of appetite?”

“I eat like a horse.”

“One more question, and you’ll pardon me, but I have to ask.”

“Ask away. Anything.”

“There’s no way this is a practical joke, right? Pulling the leg of the old retired sawbones?”

“Absolutely not,” Scott said. “I guess I don’t have to ask if you’ve ever seen a similar case, but have you ever read about one?”

Ellis shook his head. “Like you, it’s the clothes that I keep coming back to. And the quarters in your coat pockets.”

Join the club, Scott thought.

“No one weighs the same naked as they do dressed. It’s as much a given as gravity.”

“Are there medical websites you can go on to see if there are any other cases like mine? Even ones that are sort of similar?”

“I can and will, but I can tell you now there won’t be.” Ellis hesitated. “This isn’t just outside my experience, I’d say it’s outside human experience. Hell, I want to say it’s impossible. If, that is, your scale and mine weigh true, and I have no reason to believe otherwise. What happened to you, Scott? What was the genesis? Did you . . . I don’t know, get irradiated by something? Maybe get a lungful of some off-brand bug-spray? Think.”

“I have thought. So far as I can tell, there’s nothing. But one thing’s for sure, I feel better having talked to you. Not just sitting on it.” Scott stood up and grabbed his jacket.

“Where are you going?”

“Home. I’ve got those websites to work on. It’s a big deal. Although I have to tell you, it doesn’t seem quite as big as it did.”

Ellis walked with him to the door. “You say you’ve noted a steady weight-loss. Slow but steady.”

“That’s right. A pound or so a day.”

“No matter how much you eat.”

“Yes,” Scott said. “And what if it continues?”

“It won’t.”

“How can you be sure? If it’s outside of human experience?”

To this Doctor Bob had no answer.

“Keep your mouth shut about this, Bob. Please.”

“I will if you promise to keep me informed. I’m concerned.”

“That I can do.”

On the stoop, they stood side by side, looking at the day. It was a nice one. Foliage was nearing peak, and the hills were burning with color. “Moving from the sublime to the ridiculous,” Doctor Bob said, “how are you doing with the restaurant ladies up the street from you? Heard you were having some problems there.”

Scott didn’t bother asking Ellis where he had heard this; Castle Rock was a small town, and word got around. It got around faster, he supposed, when a retired doctor’s wife was on all sorts of town and church committees. “If Ms. McComb and Ms. Donaldson heard you calling them ladies, you’d be in their black books. And given my current problem, they’re not even on my radar.”

* * *

An hour later Scott sat in his own study, part of a handsome three-decker on Castle View, above the town proper. A pricier address than he had been comfortable with, but Nora had wanted it, and he had wanted Nora. Now she was in Arizona and he was left with a place that had been too big even when it had been the two of them. Plus the cat, of course. He had an idea she had found it harder to leave Bill than to leave him. Scott recognized that was a little bitchy, but how often the truth was.

In the center of his computer screen, in big letters, were the words HOCHSCHILD-KOHN DRAFT SITE 4 MATERIAL. Hochschild-Kohn wasn’t the chain he was working for, had been out of business for nearly forty years, but with a job as big as this one, it didn’t hurt to be mindful of hackers. Hence the pseudonym.

When Scott double-clicked, a picture of an old-timey Hochschild-Kohn department store appeared (eventually to be replaced by a much more modern building, belonging to the actual company that had hired him). Below this: You bring the inspiration, we bring the rest.

It was this tossed-off tagline that had actually gotten him the job. Design skills were one thing; inspiration and clever sloganeering were another; when they came together, you had something special. He was special, this was his chance to prove it, and he intended to make the most of it. Eventually he would be working with an ad agency, he understood that, and they would tinker with his lines and graphics, but he thought that slogan would stay. Most of his basic ideas would also stay. They were strong enough to survive a bunch of New York City hotshots.

He double-clicked again, and a living room appeared on the screen. It was totally empty; there weren’t even light fixtures. Outside the window was a greensward that just happened to be part of the Highland Acres golf course, where Myra Ellis had played many rounds. On a few occasions, Myra’s foursome had included Scott’s own ex-wife, who was now living (and presumably golfing) in Flagstaff.

Bill D. Cat came in, gave a sleepy miaow, and rubbed along his leg.

“Food soon,” Scott murmured. “Few more minutes.” As though a cat had any concept of minutes in particular, or time in general.

As if I do, Scott thought. Time is invisible. Unlike weight.

Ah, but maybe that wasn’t true. You could feel weight, yes—when you were carrying too much, it made you ploddy—but wasn’t it, like time, basically just a human construct? Hands on a clock, numbers on a bathroom scale, weren’t they only ways of trying to measure invisible forces that had visible effects? A feeble effort to corral some greater reality beyond what mere humans thought of as reality?

“Let it go, you’ll drive yourself bugshit.”

Bill gave another miaow, and Scott returned his attention to the computer screen.

Above the barren living room was a search field containing the words Pick Your Style!Scott typed in Early American, and the screen came to life, not all at once, but slowly, as if each piece of furniture were being picked out by a careful shopper and added to the whole: chairs, a sofa, pink walls that were stenciled rather than papered, a Seth Thomas clock, a goodwife rag rug on the floor. A fireplace with a small cozy blaze within. The overhead fixture held hurricane lamps on wooden spokes. Those were a little over the top for Scott’s taste, but the salespeople he was dealing with loved them, and assured Scott that potential customers would, too.

He could swipe and furnish a parlor, a bedroom, a study, all in Early American. Or he could return to the search field and furnish those virtual-reality rooms in Colonial, Garrison, Craftsman, or Cottage style. Today’s job, however, was Queen Anne. Scott opened his laptop and began picking out display furniture.

Forty-five minutes later, Bill was back, rubbing and miaowing more insistently.

“Okay, okay,” Scott said, and got up. He went into the kitchen, Bill D. Cat leading the way with his tail up. There was a feline spring in Bill’s step, and Scott was damned if he didn’t feel pretty springy himself.

He dumped Friskies into Bill’s bowl, and while the cat chowed down, he went out on the front porch for a breath of fresh air before going back to Selby wing chairs, Winfrey settees, Houzz highboys, all with the famous Queen Anne legs. He thought it was the kind of furniture you saw in funeral parlors, heavy shit trying to seem light, but different strokes for different folks.

He was in time to see “the ladies,” as Doctor Bob had called them, coming out of their driveway and turning onto View Drive, long legs flashing beneath tiny shorts—blue for Deirdre McComb, red for Missy Donaldson. They were wearing identical tee-shirts advertising the restaurant they ran downtown on Carbine Street. Following them were their nearly identical boxers, Dum and Dee.

What Doctor Bob had said as Scott was leaving (probably wanting no more than to end their meeting on a lighter note) now recurred, something about Scott having a little trouble with the restaurant ladies. Which he was. Not a bitter relationship problem, or a mysterious weight-loss problem; more like a cold sore that wouldn’t go away. Deirdre was the really annoying one, always with her faintly superior smile—the one that seemed to say lord help me to bear these fools.

Scott made a sudden decision and hustled back to his study (taking a nimble leap over Bill, who was reclining in the hall) and grabbed his tablet. Running back to the porch, he opened the camera app.

The porch was screened, which made him hard to see, and the women weren’t paying any attention to him, anyway. They ran along the packed dirt shoulder on the far side of the Drive with their bright white sneakers scissoring and their ponytails swinging. The dogs, stocky but still young and plenty athletic, pounded along behind.

Scott had visited their home twice on the subject of those dogs, had spoken to Deirdre both times, and had borne that faintly superior smile patiently as she told him she really doubted that their dogs were doing their business on his lawn. Their backyard was fenced, she said, and in the hour or so each day when they were out (“Dee and Dum always accompany Missy and me on our daily runs”) they were very well-behaved.

“I think they must smell my cat,” Scott had said. “It’s a territorial thing. I get that, and I understand you not wanting to leash them when you run, but I’d appreciate you checking out my lawn when you come back, and policing it up if necessary.”

“Policing,” Deirdre had said, her smile never wavering. “Seems a bit militaristic, but maybe that’s just me.”

“Whatever you want to call it.”

“Mr. Carey, dogs may be, as you say, doing their business on your lawn, but they’re not our dogs. Perhaps it’s something else that’s concerning you? It wouldn’t be a prejudice against same-sex marriage, would it?”

Scott had almost laughed, which would have been bad—even Trumpian—diplomacy. “Not at all. It’s a prejudice against not wanting to step in a surprise package left by one of your boxers.”

“Good discussion,” she had said, still with that smile (not maddening, as she might have hoped, but definitely irritating), and closed the door gently but firmly in his face.

With his mysterious weight-loss the farthest thing from his mind for the first time in days, Scott watched the two women running toward him with their dogs loping gamely along in their wake. Deirdre and Missy were talking as they ran, laughing about something. Their flushed cheeks shone with sweat and good health. The McComb woman was clearly the better runner of the two, and just as clearly holding back a bit to stay with her partner. They were paying zero attention to the dogs, which was hardly neglect; View Drive wasn’t a hotbed of traffic, especially in the middle of the day. And Scott had to admit that the dogs were good about keeping out of the road. In that, at least, they were well-trained.

Not going to happen today, he thought. It never does when you’re prepared. Yet it would be pleasant to wipe that little quirk of a smile off Ms. McComb’s—

But it did happen. First one of the boxers swerved, then the other followed. Dee and Dum ran onto Scott’s lawn and squatted side by side. Scott raised his tablet and snapped three quick photos.

* * *

That evening, after an early supper of spaghetti carbonara followed by a wedge of chocolate cheesecake, Scott got on his Ozeri scale, hoping as he always did these days that things had finally started going the right way. They had not. In spite of the big meal he had just put away, the Ozeri informed him that he was down to 210.8 pounds.

Bill was watching him from the closed toilet seat, his tail curled neatly around his paws. “Well,” Scott told him, “it is what it is, right? As Nora used to say when she came home from those meetings of hers, life is what we make it and acceptance is the key to all our affairs.”

Bill yawned.

“But we also change the things we can, don’t we? You hold the fort. I’m going to pay a visit.”

He grabbed his iPad and jogged the quarter mile to the renovated farmhouse where McComb and Donaldson had lived for the last eight months or so, since opening Holy Frijole. He knew their schedule pretty well, in the offhand way one gets to know one’s neighbors’ comings and goings, and this would be a good time to catch Deirdre alone. Missy was the chef at the restaurant, and usually left to start dinner prep around three. Deirdre, who was the out-front half of the partnership, came around five. She was the one in charge, Scott believed, both at work and at home. Missy Donaldson impressed him as a sweet little thing who looked at the world with a mixture of fear and wonder. More of the former than the latter, he guessed. Did McComb see herself as Missy’s protector as well as her partner? Maybe. Probably.

He mounted the steps and rang the doorbell. At its chime, Dee and Dum began to bark in the backyard.

Deirdre opened the door. She was dressed in a pretty, figure-fitting dress that would no doubt look smashing as she stood at the hostess stand and then showed parties to their various tables. Her eyes were her best feature, a bewitching shade of greeny-gray and uptilted a bit at the corners.

“Oh, Mr. Carey,” she said. “How really nice to see you.” And the smile, which said how really boring to see you. “I’d love to invite you in, but I have to get down to the restaurant. Lots of reservations tonight. Leaf-peepers, you know.”

“I won’t keep you,” Scott said, smiling his own smile. “I just dropped by to show you this.” And he held up his iPad, so she could observe Dee and Dum squatting on his front lawn and shitting in tandem.

She looked at it for a long time, the smile fading. Seeing that didn’t give him as much pleasure as he had expected.

“All right,” she said at last. The artificial lilt had gone out of her voice. Without it she sounded tired and older than her years, which might number thirty. “You win.”

“It’s not about winning, believe me.” As it came out of his mouth, Scott remembered a college teacher once remarking that when someone added believe me to a sentence, you should beware.

“You’ve made your point, then. I can’t come down and pick it up now, and Missy’s already at work, but I will after we close. You won’t even need to turn on your porch light. I should be able to see the . . . leavings . . . by the streetlight.”

“You don’t need to do that.” Scott was starting to feel slightly mean. And in the wrong, somehow. You win, she’d said. “I’ve already bagged it up. I just . . .”

“What? Wanted to get one up on me? If that was it, mission accomplished. From now on Missy and I will do our running down in the park. There will be no need for you to report us to the local authorities. Thank you, and good evening.” She started to close the door.

“Wait a second,” Scott said. “Please.”

She looked at him through the half-closed door, face expressionless.

“Going to the animal control guy over a few piles of dog crap never crossed my mind, Ms. McComb. Look, I just want us to be good neighbors. My only problem was the way you brushed me off. Refused to take me seriously. That isn’t how good neighbors do. At least not around here.”

“Oh, we know exactly how good neighbors do,” she said. “Around here.” The slightly superior smile came back, and she closed the door with it still on her face. Not before, however, he had seen a gleam in her eyes that might have been tears.

We know exactly how good neighbors do around here, he thought, walking back down the hill. What the hell did that mean?

* * *

Doctor Bob called him two days later, to ask if there had been any change. Scott told him things were progressing as before. He was down to 207.6. “It’s pretty damn regular. Getting on the bathroom scale is like watching the numbers go backward on a car odometer.”

“But still no change in your physical dimensions? Waist size? Shirt size?”

“I’m still a forty waist and a thirty-four leg. I don’t need to tighten my belt. Or let it out, although I’m eating like a lumberjack. Eggs, bacon, and sausage for breakfast. Sauces on everything at night. Got to be at least three thousand calories a day. Maybe four. Did you do any research?”

“I did,” Doctor Bob said. “So far as I can tell, there’s never been a case like yours. There are plenty of clinical reports about people whose metabolisms are in overdrive—people who eat, as you say, like lumberjacks and still stay thin—but no cases of people who weigh the same naked and dressed.”

“Oh, but it’s so much more,” Scott said. He was smiling again. He smiled a lot these days, which was probably crazy, given the circumstances. He was losing weight like a late-stage cancer patient, but the work was going like gangbusters and he had never felt more cheerful. Sometimes, when he needed a break from the computer screen, he put on Motown and danced around the room with Bill D. Cat staring at him as if he’d gone mad.

“Tell me the more.”

“This morning I weighed 208 flat. Straight out of the shower and buck naked. I got my hand-weights out of the closet, the twenty-pounders, and stepped on the scales with one in each hand. Still 208 flat.”

Silence on the other end for a moment, then Ellis said, “You’re shitting me.”

“Bob, if I’m lyin, I’m dyin.”

More silence. Then: “It’s as if you’ve got some kind of weight-repelling force-field around you. I know you don’t want to be poked and prodded, but this is an entirely new thing. And it’s big. There could be implications we can’t even conceive of.”

“I don’t want to be a freak,” Scott said. “Put yourself in my place.”

“Will you at least think about it?”

“I have, a lot. And I have no urge to be a part of Inside View’s tabloid hall of fame, with my picture right between the Night Flier and Slender Man. Also, I’ve got my work to finish. I’ve promised Nora a share of the money even though the divorce was final before I got the job, and I’m pretty sure she can use it.”

“How long will that take?”

“Maybe six weeks. Of course there’ll be revisions and test runs that will keep me busy into the new year, but six weeks to finish the main job.”

“If this continues at the same rate, you’d be down around 165 by then.”

“But still looking like a mighty man,” Scott said, and laughed. “There’s that.”

“You sound remarkably cheery, considering what’s going on with you.”

“I feel cheerful. That might be nuts, but it’s true. Sometimes I think this is the world’s greatest weight-loss program.”

“Yes,” Ellis said, “but where does it end?”

* * *

One day not long after his phone conversation with Doctor Bob, there came a light knock at Scott’s front door. If he’d had his music turned up any louder—today it was the Ramones—he never would have heard it, and his visitor might have gone away. Probably with relief, because when he opened the front door, Missy Donaldson was standing there, and she looked scared half to death. It was the first time he’d seen her since taking the photos of Dee and Dum relieving themselves on his lawn. He supposed Deirdre had been as good as her word, and the women were now exercising their dogs in the town park. If they were allowing the boxers to run free down there, they really might run afoul of the animal control guy, no matter how well-behaved the dogs were. The park had a leash law. Scott had seen the signs.

“Ms. Donaldson,” he said. “Hello.”

It was also the first time he’d seen her alone, and he was careful not to step over the threshold or make any sudden moves. She looked like she might leap down the steps and run away like a deer if he did. She was blond, not as pretty as her partner, but with a sweet face and clear blue eyes. There was a fragility about her, something that made Scott think of his mother’s decorative china plates. It was hard to imagine this woman in a restaurant kitchen, moving from pot to pot and skillet to skillet through the steam, plating veggie dinners and bossing around the help while she did it.

“Can I help you? Would you like to come in? I have coffee . . . or tea, if you prefer.”

She was shaking her head before he was halfway through these standard offers of hospitality, and doing it hard enough to make her ponytail flip from one shoulder to the other. “I just came to apologize. For Deirdre.”

“There’s no need to do that,” he said. “And no need to take your dogs all the way down to the park, either. All I ask is that you carry a couple of poop bags and check out my lawn on your way back. That’s not too much to ask, is it?”

“No, not at all. I even suggested it to Deirdre. She almost snapped my head off.”

Scott sighed. “I’m sorry to hear that. Ms. Donaldson—”

“You can call me Missy, if you like.” Looking down and blushing slightly, as if she’d made a remark that might be taken for risqué.

“I would like that. Because all I want is for us to be good neighbors. Most of the folks up here on the View are, you know. And I seem to have gotten off on the wrong foot, although how I could have gotten off on the right one, I don’t know.”

Still looking down, she said, “We’ve been here for almost eight months, and the only time you’ve really talked to us—either of us—was when our dogs messed on your lawn.”

This was truer than Scott would have liked. “I came up with a bag of doughnuts after you moved in,” he said (rather weakly), “but you weren’t at home.”

He thought she would ask why he hadn’t tried again, but she didn’t.

“I came to apologize for Deirdre, but I also wanted to explain her.” She raised her eyes to his. It took an obvious effort—her hands were clenched together at the waist of her jeans—but she did it. “She’s not mad at you, really . . . well, she is, but you’re not the only one. She’s mad at everybody. Castle Rock was a mistake. We came here because the place was almost business-ready, the price was right, and we wanted to get out of the city—Boston, I mean. We knew it was a risk, but it seemed like an acceptable one. And the town is so beautiful. Well, you know that, I guess.”

Scott nodded.

“But we’re probably going to lose the restaurant. If things don’t turn around by Valentine’s Day, for sure. That’s the only reason she let them put her on that poster. She won’t talk about how bad things are, but she knows it. We both do.”

“She said something about the leaf-peepers . . . and everyone says last summer was especially good . . .”

“The summer was good,” she said, speaking with a little more animation now. “As for the leaf-peepers, we get some, but most of them go further west, into New Hampshire. North Conway has all those outlet stores to shop in, and more touristy stuff to do. I guess when winter comes we’ll get the skiers passing through on their way to Bethel or Sugarloaf . . .”

Scott knew most skiers bypassed the Rock, taking Route 2 to the western Maine ski areas, but why bum her out more than she already was?

“Only when winter comes, we’d need the locals to pull us through. You know how it is, you must. The locals trade with other locals during the cold weather, and it’s just enough to tide them over until the summer people come back. The hardware store, the lumberyard, Patsy’s Diner . . . they make do through the lean months. Only not many locals come to Frijole. Some, but not enough. Deirdre says it’s not just because we’re lesbians, but because we’re married lesbians. I don’t like to think she’s right . . . but I think she is.”

“I’m sure . . .” He trailed off. That it isn’t true? How in hell did he know, when he’d never even considered it?

“Sure of what?” she asked. Not in a snotty way, but in an honestly curious one.

He thought of his bathroom scale again, and the relentless way the numbers rolled back. “Actually, I’m sure of nothing. If it’s true, I’m sorry.”

“You should come down for dinner some night,” she said. This might have been a snide way of telling him she knew he’d never taken a meal at Holy Frijole, but he didn’t think so. He didn’t think this young woman had much in the way of snideness in her.

“I will,” he said. “I assume you do have frijoles?”

She smiled. It lit her up. “Oh yes, many kinds.”

He smiled back. “Stupid question, I guess.”

“I have to go, Mr. Carey—”

“Scott.”

She nodded. “All right, Scott. It’s good to talk to you. It took all my courage to come down here, but I’m glad I did.”

She held out her hand. Scott shook it.

“Just one favor. If you happen to see Deirdre, I’d appreciate you not mentioning that I came to see you.”

“Done deal,” Scott said.

* * *

The day after Missy Donaldson’s visit, while he was sitting at the counter in Patsy’s Diner and finishing his lunch, Scott heard someone behind him at one of the tables say something about “that crack-snackin’ restaurant.” Laughter followed. Scott looked at his half-eaten wedge of apple pie and the scoop of vanilla ice cream now puddling around it. It had looked good when Patsy set it down, but he no longer wanted it.

Had he heard such remarks before, and just filtered them out, the way he did with most overheard but unimportant (to him, at least) chatter? He didn’t like to think so, but it was possible.

Probably going to lose the restaurant, she’d said. We’d have to count on the locals to pull us through.

She’d used the conditional tense, as if Holy Frijole already had a FOR SALE OR LEASE sign in the window.

He got up, left a tip under his dessert plate, and paid his check.

“Couldn’t finish the pie?” Patsy asked.

“My eyes were a little bigger than my stomach,” Scott said, which wasn’t true. His eyes and stomach were the same size they’d always been; they just weighed less. The amazing thing was that he didn’t care more, or even worry much. Unprecedented it might be, but sometimes his steady weight-loss slipped his mind completely. It had when he’d been waiting to snap photos of Dee and Dum squatting on his lawn. And it did now. What was on his mind at this moment was that crack about crack-snackers.

Four guys were sitting at the table the remark had come from, beefy fellows in work clothes. A row of hardhats sat in a line on the windowsill. The men were wearing orange vests with CRPW stenciled on them: Castle Rock Public Works.

Scott walked past them to the door, opened it, then changed his mind and went to the table where the road crew sat. He recognized two of the men, had played poker with one of them, Ronnie Briggs. Townies, like him. Neighbors.

“You know what, that was a shitty thing to say.”

Ronnie looked up, puzzled, then recognized Scott and grinned. “Hey, Scotty, how you doin?”

Scott ignored him. “Those women live just up the road from me. They’re okay.” Well, Missy was. About McComb he wasn’t so sure.

One of the other men crossed his arms over his broad chest and stared at Scott. “Were you in this conversation?”

“No, but—”

“Right. So butt out.”

“—but I had to listen to it.”

Patsy’s was small, but always crammed at lunchtime and filled with chatter. Now the talk and the busy gnash of forks on plates stopped. Heads turned. Patsy stood beside the cash register, alert for trouble.

“Once again, buddy, butt out. What we talk about is none of your business.”

Ronnie got up in a hurry. “Hey, Scotty, why don’t I walk out with you?”

“No need,” Scott said. “I don’t need an escort, but I have to say something first. If you eat there, the food is your business. You can criticize it all you want. What those women do in the rest of their lives is not your business. Got it?”

The one who had asked Scott if he had been invited into their conversation uncrossed his arms and stood up. He wasn’t as tall as Scott, but he was younger and muscular. Red had crept up his broad neck and into his cheeks. “You need to take your loud mouth out of here before I punch it for you.”

“None of that, none of that, now,” Patsy said sharply. “Scotty, you need to leave.”

He stepped out of the diner without argument, and took a deep breath of the cool October air. There was a knock on the glass from behind him. Scott turned and saw Bull Neck looking out. He raised a finger as if to say hang on a second. There were all sorts of posters in Patsy’s window. Bull Neck pulled one of them free, walked to the door, and opened it.

Scott balled his fists. He hadn’t been in a fist-fight since grammar school (an epic battle that had lasted fifteen seconds, six punches thrown, four of them clean misses), but he was suddenly looking forward to this one. He felt light on his feet, more than ready. Not angry; happy. Optimistic.

Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, he thought. Come on, big boy.

But Bull Neck didn’t want to fight. He crumpled up the poster and threw it on the sidewalk at Scott’s feet. “Here’s your girlfriend,” he said. “Take it home and jerk off over it, why don’t you? Short of rape, it’s the closest you’ll ever get to fucking her.”

He went back in and sat down with his mates, looking satisfied: case closed. Aware that everyone in the diner was looking at him through the window, Scott bent down, picked up the crumpled poster, and walked away toward noplace in particular, just wanting not to be stared at. He didn’t feel ashamed of himself, or stupid for starting something in the diner where half of the Rock ate lunch, but all those interested eyes were annoying. It made him wonder why anyone would want to get up on a stage to sing or act or tell jokes.

He smoothed out the ball of paper, and the first thing he thought of was something Missy Donaldson had said: That’s the only reason she let them put her on that poster. “Them,” it seemed, was the Castle Rock Turkey Trot Committee.

In the center of the sheet was a photo of Deirdre McComb. There were other runners, most of them behind her. A big number 19 was pinned to the waistband of her tiny blue shorts. Above them was a tee-shirt with NEW YORK CITY MARATHON 2011 on the front. On her face was an expression Scott would not have associated with her: blissful happiness.

The caption read: Deirdre Mc Comb, co-owner of Holy Frijole, Castle Rock’s newest fine dining experience, nears the finish line of the New York City Marathon, where she finished FOURTH in the Women’s Division! She’s announced that she will run in this year’s Castle Rock 12K, the Turkey Trot. HOW ABOUT YOU?

The details were below the caption. Castle Rock’s annual Thanksgiving race would take place on the Friday following the holiday, starting at the Rec Department on Castle View and finishing downtown, at the Tin Bridge. All ages were welcome, adult entrance fee five dollars for locals, seven dollars for out-of-towners, and two dollars for those under fifteen, sign up at the Castle Rock Rec Department.

Looking at the bliss on the face of the woman in the photo—runner’s high at its purest—Scott understood that Missy hadn’t been exaggerating about Holy Frijole’s life-expectancy. Not in the slightest. Deirdre McComb was a proud woman with a high opinion of herself, and quick—much too quick, in Scott’s opinion—to take offense. Her allowing her picture to be used this way, probably just for that mention of “Castle Rock’s newest fine dining experience,” had to be a Hail Mary pass. Anything, anything at all, to bring in a few more customers, if only to admire those long legs standing beside the hostess station.

He folded the poster, tucked it into the back pocket of his jeans, and walked slowly down Main Street, looking in shop windows as he went. There were posters in all of them—posters for bean suppers, posters for this year’s giant yard sale in the parking lot of Oxford Plains Speedway, posters for Beano at the Catholic church and a potluck dinner at the fire station. He saw the Turkey Trot poster in the window of Castle Rock Computer Sales & Service, but nowhere else until he reached the Book Nook, a tiny building at the end of the street.

He went in, browsed a little, and grabbed a picture book from the discount table: New England Fixtures and Furnishings. Might not be anything in it he could use in his project—where the first stage was nearing completion, anyway—but you never knew. While he was paying Mike Badalamente, the owner and sole employee, he remarked on the poster in the window, and mentioned that the woman on it was his neighbor.

“Yeah, Deirdre McComb was a star runner for almost ten years,” Mike said, bagging up his book. “She would have been in the Olympics back in ’12, except she broke her ankle. Tough luck. Never even tried out in ’16, I understand. I guess she’s retired from the major competitions now, but I can’t wait to run with her this year.” He grinned. “Not that I’ll be running with her long, once the starting gun goes off. She’ll blow the competition away.”

“Men as well as women?”

Mike laughed. “Buddy, they didn’t call her the Malden Flash for nothing. Malden’s where she originally came from.”

“I saw a poster in Patsy’s, and one in the window of the computer store, and the one in your window. Nowhere else. What’s up with that?”

Mike’s smile went away. “Nothing to be proud of. She’s a lesbian. That would probably be okay if she kept it to herself—no one cares what goes on behind closed doors—but she has to introduce that one who cooks at Frijole as her wife. Lot of people around here see that as a big old screw you.”

“So businesses won’t put up the posters, even though the entry fees benefit the Rec? Just because she’s on them?”

After having Bull Neck throw the poster from the diner at him, these weren’t even real questions, just a way of getting it straight in his mind. In a way he felt as he had at ten, when the brother of his best friend had sat the younger boys down and told them the facts of life. Now as then, Scott had had a vague idea of the whole, but the specifics were still amazing to him. People really did that? Yes, they did. Apparently they did this, as well.

“They’re going to be replaced with new ones,” Mike said. “I happen to know, because I’m on the committee. It was Mayor Coughlin’s idea. You know Dusty, the king of compromise. The new ones will show a bunch of turkeys running down Main Street. I don’t like it, and I didn’t vote for it, but I understand the rationale. The town just gives the Rec a pittance, two thousand dollars. That’s not enough to maintain the playground, let alone all the other stuff we do. The Turkey Trot brings in almost fivethousand, but we have to get the word out.”

“So . . . just because she’s a lesbian . . .”

“A married lesbian. That’s a deal-breaker for lots of folks. You know what Castle County’s like, Scott, you’ve lived here for what, twenty-five years?”

“Over thirty.”

“Yeah, and solid Republican. Conservative Republican. The county went for Trump three-to-one in ’16 and they think our stonebrain governor walks on water. If those women had kept it on the down-low they would have been fine, but they didn’t. Now there are people who think they’re trying to make some kind of statement. Myself, I think they were either ignorant about the political climate here or plain stupid.” He paused. “Good food, though. Have you been there?”

“Not yet,” Scott said, “but I plan to go.”

“Well, don’t wait too long,” Mike said. “Come next year at this time, there’s apt to be an ice cream shop in there.”