【Biomechanics】1 Biomechanics as an Interdiscipline

| 无 | 回到目录 | 第2章 |

|---|

文章目录

-

- 1.0 Introduction

- 1.1 Measurement, Description, Analysis, and Assessment

- 1.1.1 Measurement, Description, and Monitoring

-

- 1.1.2 Analysis

- 1.1.3 Assessment and Interpretation

- 1.2 Biomechanics and its Relationship with Physiology and Anatomy

- 1.3 Scope of the Textbook

-

- 1.3.1 Signal Processing

1.0 Introduction

The biomechanics of human movement can be defined as the interdiscipline that describes, analyzes, and assesses human movement. A wide variety of physical movements are involved—everything from the gait of the physically handicapped to the lifting of a load by a factory worker to the performance of a superior athlete. The physical and biological principles that apply are the same in all cases. What changes from case to case are the specific movement tasks and the level of detail that is being asked about the performance of each movement.

人类运动的生物力学可以定义为描述、分析和评估人类运动的跨学科领域。涉及到各种各样的身体动作,包括残障人士的步态、工厂工人的搬运以及优秀运动员的表现等。适用的物理和生物学原理在所有情况下都是相同的。不同的是每种情况下的具体运动任务和对每个运动表现的详细要求。

The list of professionals and semiprofessionals interested in applied aspects of human movement is quite long: orthopedic surgeons, athletic coaches, rehabilitation engineers, therapists, kinesiologists, prosthetists, psychiatrists, orthotists, sports equipment designers, and so on. At the basic level, the name given to the science dedicated to the broad area of human movement is kinesiology. It is an emerging discipline blending aspects of psychology, motor learning, and exercise physiology as well as biomechanics. Biomechanics, as an outgrowth of both life and physical sciences, is built on the basic body of knowledge of physics, chemistry, mathematics, physiology, and anatomy. It is amazing to note that the first real “biomechanicians” date back to Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Lagrange, Bernoulli, Euler, and Young. All these scientists had primary interests in the application of mechanics to biological problems.

对于对人类运动应用方面感兴趣的专业人士和半专业人士的名单非常长:骨科外科医生、运动教练、康复工程师、治疗师、运动学家、假肢制造师、精神科医生、矫形器制造师、体育器材设计师等等。在基础层面上,专注于人类运动广泛领域的科学被称为运动学。它是一门新兴学科,融合了心理学、运动学习、运动生理学以及生物力学的方面。生物力学作为生命科学和物理科学的产物,建立在物理学、化学、数学、生理学和解剖学的基础知识上。令人惊奇的是,第一批真正的"生物力学家"可以追溯到达·芬奇、伽利略、拉格朗日、伯努利、欧拉和杨。所有这些科学家都对将力学应用于生物问题有着主要兴趣。

1.1 Measurement, Description, Analysis, and Assessment

The scientific approach as applied to biomechanics has been characterized by a fair amount of confusion. Some descriptions of human movement have been passed off as assessments, some studies involving only measurements have been falsely advertised as analyses, and so on. It is, therefore, important to clarify these terms. Any quantitative assessment of human movement must be preceded by a measurement and description phase, and if more meaningful diagnostics are needed, a biomechanical analysis is usually necessary. Most of the material in this text is aimed at the technology of measurement and description and the modeling process required for analysis. The final interpretation, assessment, or diagnosis is movement specific and is limited to the examples given.

在应用于生物力学的科学方法中存在相当多的混淆。一些对人类运动的描述被误传为评估,一些仅涉及测量的研究被错误地宣传为分析等等。因此,澄清这些术语非常重要。任何对人类运动的定量评估都必须先经过测量和描述阶段,如果需要更有意义的诊断,通常需要进行生物力学分析。本文大部分内容都针对测量和描述的技术以及分析所需的建模过程。最终的解释、评估或诊断是与运动具体相关的,并且仅限于所给出的示例。

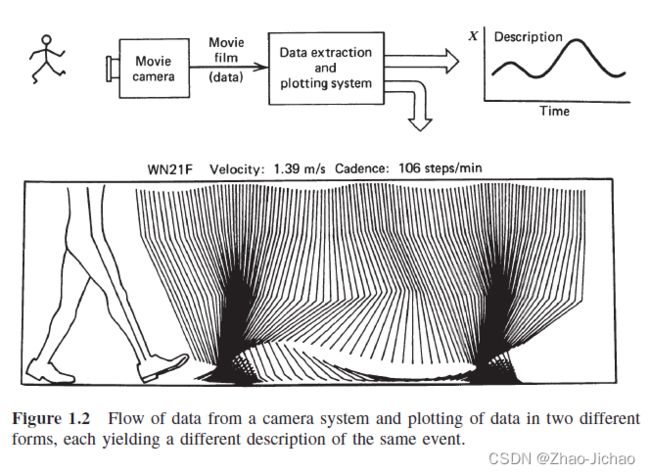

Figure 1.1, which has been prepared for the assessment of the physically handicapped, depicts the relationships between these various phases of assessment. All levels of assessment involve a human being and are based on his or her visual observation of a patient or subject, recorded data, or some resulting biomechanical analysis. The primary assessment level uses direct observation, which places tremendous “overload” even on the most experienced observer. All measures are subjective and are almost impossible to compare with those obtained previously. Observers are then faced with the tasks of documenting (describing) what they see, monitoring changes, analyzing the information, and diagnosing the causes. If measurements can be made during the patient’s movement, then data can be presented in a convenient manner to describe the movement quantitatively. Here the assessor’s task is considerably simplified. He or she can now quantify changes, carry out simple analyses, and try to reach a more objective diagnosis. At the highest level of assessment, the observer can view biomechanical analyses that are extremely powerful in diagnosing the exact cause of the problem, compare these analyses with the normal population, and monitor their detailed changes with time.

为了评估身体残疾人,已经为图1.1准备了一份图表,展示了评估的各个阶段之间的关系。所有评估层次都涉及到一个人类,并且基于他或她对患者或受试者的视觉观察、记录的数据或某种生物力学分析结果。主要的评估层次使用直接观察,这对于最有经验的观察者来说是巨大的负担。所有的测量都是主观的,几乎不可能与之前获得的结果进行比较。观察者面临的任务是记录(描述)他们所看到的情况,监测变化,分析信息和诊断原因。如果可以在患者的运动过程中进行测量,那么数据可以以便捷的方式定量描述运动。在这里,评估者的任务得到了极大的简化。现在他们可以量化变化,进行简单的分析,并尝试得出更客观的诊断。在评估的最高层次,观察者可以查看非常强大的生物力学分析结果,从而准确诊断问题的根本原因,将这些分析结果与正常人群进行比较,并随时间监测其详细变化。

The measurement and analysis techniques used in an athletic event could be identical to the techniques used to evaluate an amputee’s gait. However, the assessment of the optimization of the energetics of the athlete is quite different from the assessment of the stability of the amputee. Athletes are looking for very detailed but minor changes that will improve their performance by a few percentage points, sufficient to move them from fourth to first place. Their training and exercise programs and reassessment normally continue over an extended period of time. The amputee, on the other hand, is looking for major improvements, probably related to safe walking, but not fine and detailed differences. This person is quite happy to be able to walk at less than maximum capability, although techniques are available to permit training and have the prosthesis readjusted until the amputee reaches some perceived maximum. In ergonomic studies, assessors are likely looking for maximum stresses in specific tissues during a given task, to thereby ascertain whether the tissue is working within safe limits. If not, they will analyze possible changes in the workplace or task in order to reduce the stress or fatigue.

在运动项目中使用的测量和分析技术可能与评估截肢者步态的技术完全相同。然而,对于运动员能量优化的评估与截肢者稳定性的评估是完全不同的。运动员正在寻求非常详细但微小的改变,这些改变将使他们的表现提高几个百分点,足以将他们从第四名提升到第一名。他们的训练和锻炼计划以及重新评估通常会持续很长一段时间。另一方面,截肢者正在寻求重大的改善,可能与安全行走有关,但不涉及细微的差异。尽管存在一些训练和矫形装置调整的技术,使截肢者达到某种认知上的最大能力,但这个人很高兴能够以不到最大能力行走。在人体工程学研究中,评估者通常会寻找特定任务中特定组织的最大应力,以确定该组织是否在安全限制范围内工作。如果不是,他们将分析工作场所或任务中可能的变化,以减少压力或疲劳。

1.1.1 Measurement, Description, and Monitoring

It is difficult to separate the two functions of measurement and description. However, for clarity the student should be aware that a given measurement device can have its data presented in a number of different ways. Conversely, a given description could have come from several different measurement devices.

很难将测量和描述这两个功能分开。然而,为了清晰起见,学生应该意识到一个给定的测量设备可以以多种不同的方式呈现其数据。反过来,一个给定的描述可能来自几个不同的测量设备。

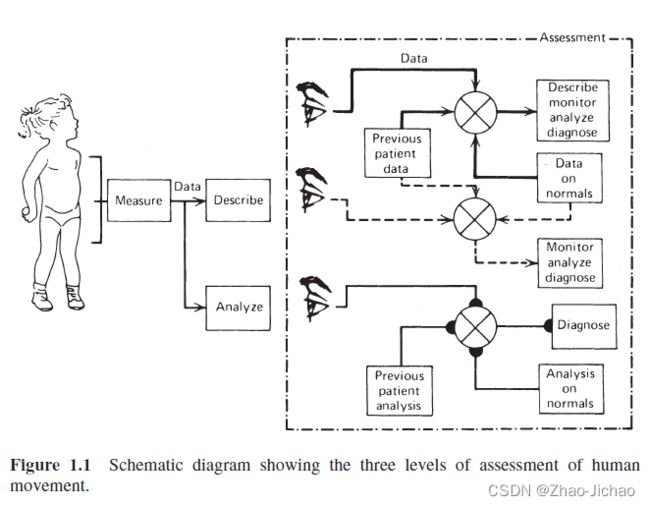

Earlier biomechanical studies had the sole purpose of describing a given movement, and any assessments that were made resulted from visual inspection of the data. The description of the data can take many forms: pen recorder curves, plots of body coordinates, stick diagrams, or simple outcome measures such as gait velocity, load lifted, or height of a jump. A movie camera, by itself, is a measurement device, and the resulting plots form the description of the event in time and space. Figure 1.2 illustrates a system incorporating a cine camera and two different descriptive plots. The coordinates of key anatomical landmarks can be extracted and plotted at regular intervals in time. Time history plots of one or more coordinates are useful in describing detailed changes in a particular landmark. They also can reveal to the trained eye changes in velocity and acceleration. A total description in the plane of the movement is provided by the stick diagram, in which each body segment is represented by a straight line or stick. Joining the sticks together gives the spatial orientation of all segments at any point in time. Repetition of this plot at equal intervals of time gives a pictorial and anatomical description of the dynamics of the movement. Here, trajectories, velocities, and accelerations can by visualized. To get some idea of the volume of the data present in a stick diagram, the student should note that one full page of coordinate data is required to make the complete plot for the description of the event. The coordinate data can be used directly for any desired analysis: reaction forces, muscle moments, energy changes, efficiency, and so on. Conversely, an assessment can occasionally be made directly from the description. A trained observer, for example, can scan a stick diagram and extract useful information that will give some directions for training or therapy, or give the researcher some insight into basic mechanisms of movement.

早期的生物力学研究仅仅是为了描述特定的运动,而任何进行的评估都是基于对数据的目视检查。数据的描述可以采用多种形式:笔记录器曲线、身体坐标的图形、棍子图或简单的测量指标,如步态速度、举起的负荷或跳跃的高度。电影摄像机本身就是一个测量设备,由此产生的图形形成了对事件在时间和空间中的描述。图1.2展示了一个集成了电影摄像机和两种不同描述图形的系统。关键解剖标志物的坐标可以在固定时间间隔内提取和绘制。一个或多个坐标的时间历史图在描述特定标志物的详细变化方面非常有用。它们还可以向经过训练的眼睛展示速度和加速度的变化。棍子图提供了运动平面上的整体描述,其中每个身体段都用一条直线或棍子表示。将这些棍子连接在一起可以在任何时间点上给出所有段的空间定位。以相等的时间间隔重复绘制此图形可以形象地描述运动的动力学特征。在这里,轨迹、速度和加速度可以被可视化。为了对棍子图中所包含的数据量有一些概念,学生应该注意到,为了对事件进行完整的描述,需要一整页的坐标数据。坐标数据可以直接用于任何所需的分析:反作用力、肌肉力矩、能量变化、效率等。反过来,有时可以直接从描述中进行评估。例如,经过训练的观察者可以扫描棍子图并提取有用信息,为训练或疗法提供一些指导,或者为研究人员提供有关运动基本机制的洞察。

The term monitor needs to be introduced in conjunction with the term describe. To monitor means to note changes over time. Thus, a physical therapist will monitor the progress (or the lack of it) for each physically disabled person undergoing therapy. Only through accurate and reliable measurements will the therapist be able to monitor any improvement and thereby make inferences to the validity of the current therapy. What monitoring does not tell us is why an improvement is or is not taking place; it merely documents the change. All too many coaches or therapists document the changes with the inferred assumption that their intervention has been the cause. However, the scientific rationale behind such inferences is missing. Unless a detailed analysis is done, we cannot document the detailed motor-level changes that will reflect the results of therapy or training.

术语“monitor”需要与术语“describe”一起引入。监测意味着记录随时间的变化。因此,物理治疗师将监测每个接受治疗的身体残障人士的进展情况(或缺乏进展情况)。只有通过准确可靠的测量,治疗师才能监测到任何改善,并因此对当前治疗的有效性进行推断。监测并不能告诉我们为什么会出现改善或没有改善;它只是记录变化。很多教练或治疗师只是记录变化,并暗示他们的干预是原因。然而,这种推断背后缺乏科学的合理性。除非进行详细的分析,否则我们无法记录反映治疗或训练结果的详细运动水平的变化。

1.1.2 Analysis

1.1.3 Assessment and Interpretation

1.2 Biomechanics and its Relationship with Physiology and Anatomy

1.3 Scope of the Textbook

1.3.1 Signal Processing

| 无 | 回到目录 | 第2章 |

|---|