3. 结构型模式 - 组合模式

亦称: 对象树、Object Tree、Composite

意图

组合模式是一种结构型设计模式, 你可以使用它将对象组合成树状结构, 并且能像使用独立对象一样使用它们

问题

如果应用的核心模型能用树状结构表示, 在应用中使用组合模式才有价值。

例如, 你有两类对象: 产品和 盒子 。 一个盒子中可以包含多个 产品或者几个较小的 盒子 。 这些小 盒子中同样可以包含一些 产品或更小的 盒子 , 以此类推。

假设你希望在这些类的基础上开发一个定购系统。 订单中可以包含无包装的简单产品, 也可以包含装满产品的盒子…… 以及其他盒子。 此时你会如何计算每张订单的总价格呢?

订单中可能包括各种产品, 这些产品放置在盒子中, 然后又被放入一层又一层更大的盒子中。 整个结构看上去像是一棵倒过来的树。

你可以尝试直接计算: 打开所有盒子, 找到每件产品, 然后计算总价。 这在真实世界中或许可行, 但在程序中, 你并不能简单地使用循环语句来完成该工作。 你必须事先知道所有 产品和 盒子的类别, 所有盒子的嵌套层数以及其他繁杂的细节信息。 因此, 直接计算极不方便, 甚至完全不可行。

解决方案

组合模式建议使用一个通用接口来与 产品和 盒子进行交互, 并且在该接口中声明一个计算总价的方法。

那么方法该如何设计呢? 对于一个产品, 该方法直接返回其价格; 对于一个盒子, 该方法遍历盒子中的所有项目, 询问每个项目的价格, 然后返回该盒子的总价格。 如果其中某个项目是小一号的盒子, 那么当前盒子也会遍历其中的所有项目, 以此类推, 直到计算出所有内部组成部分的价格。 你甚至可以在盒子的最终价格中增加额外费用, 作为该盒子的包装费用。

组合模式以递归方式处理对象树中的所有项目

该方式的最大优点在于你无需了解构成树状结构的对象的具体类。 你也无需了解对象是简单的产品还是复杂的盒子。 你只需调用通用接口以相同的方式对其进行处理即可。 当你调用该方法后, 对象会将请求沿着树结构传递下去。

真实世界类比

部队结构的例子。

大部分国家的军队都采用层次结构管理。 每支部队包括几个师, 师由旅构成, 旅由团构成, 团可以继续划分为排。 最后, 每个排由一小队实实在在的士兵组成。 军事命令由最高层下达, 通过每个层级传递, 直到每位士兵都知道自己应该服从的命令。

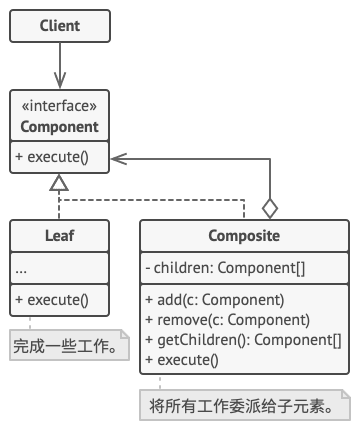

组合模式结构

-

组件 (Component) 接口描述了树中简单项目和复杂项目所共有的操作。

-

叶节点 (Leaf) 是树的基本结构, 它不包含子项目。

一般情况下, 叶节点最终会完成大部分的实际工作, 因为它们无法将工作指派给其他部分。

-

容器 (Container)——又名 “组合 (Composite)”——是包含叶节点或其他容器等子项目的单位。 容器不知道其子项目所属的具体类, 它只通过通用的组件接口与其子项目交互。

容器接收到请求后会将工作分配给自己的子项目, 处理中间结果, 然后将最终结果返回给客户端。

-

客户端 (Client) 通过组件接口与所有项目交互。 因此, 客户端能以相同方式与树状结构中的简单或复杂项目交互。

伪代码

在本例中, 我们将借助组合模式帮助你在图形编辑器中实现一系列的几何图形。

几何形状编辑器示例。

组合图形CompoundGraphic是一个容器, 它可以由多个包括容器在内的子图形构成。 组合图形与简单图形拥有相同的方法。 但是, 组合图形自身并不完成具体工作, 而是将请求递归地传递给自己的子项目, 然后 “汇总” 结果。

通过所有图形类所共有的接口, 客户端代码可以与所有图形互动。 因此, 客户端不知道与其交互的是简单图形还是组合图形。 客户端可以与非常复杂的对象结构进行交互, 而无需与组成该结构的实体类紧密耦合。

// 组件接口会声明组合中简单和复杂对象的通用操作。

interface Graphic is

method move(x, y)

method draw()

// 叶节点类代表组合的终端对象。叶节点对象中不能包含任何子对象。叶节点对象

// 通常会完成实际的工作,组合对象则仅会将工作委派给自己的子部件。

class Dot implements Graphic is

field x, y

constructor Dot(x, y) { …… }

method move(x, y) is

this.x += x, this.y += y

method draw() is

// 在坐标位置(X,Y)处绘制一个点。

// 所有组件类都可以扩展其他组件。

class Circle extends Dot is

field radius

constructor Circle(x, y, radius) { …… }

method draw() is

// 在坐标位置(X,Y)处绘制一个半径为 R 的圆。

// 组合类表示可能包含子项目的复杂组件。组合对象通常会将实际工作委派给子项

// 目,然后“汇总”结果。

class CompoundGraphic implements Graphic is

field children: array of Graphic

// 组合对象可在其项目列表中添加或移除其他组件(简单的或复杂的皆可)。

method add(child: Graphic) is

// 在子项目数组中添加一个子项目。

method remove(child: Graphic) is

// 从子项目数组中移除一个子项目。

method move(x, y) is

foreach (child in children) do

child.move(x, y)

// 组合会以特定的方式执行其主要逻辑。它会递归遍历所有子项目,并收集和

// 汇总其结果。由于组合的子项目也会将调用传递给自己的子项目,以此类推,

// 最后组合将会完成整个对象树的遍历工作。

method draw() is

// 1. 对于每个子部件:

// - 绘制该部件。

// - 更新边框坐标。

// 2. 根据边框坐标绘制一个虚线长方形。

// 客户端代码会通过基础接口与所有组件进行交互。这样一来,客户端代码便可同

// 时支持简单叶节点组件和复杂组件。

class ImageEditor is

field all: CompoundGraphic

method load() is

all = new CompoundGraphic()

all.add(new Dot(1, 2))

all.add(new Circle(5, 3, 10))

// ……

// 将所需组件组合为复杂的组合组件。

method groupSelected(components: array of Graphic) is

group = new CompoundGraphic()

foreach (component in components) do

group.add(component)

all.remove(component)

all.add(group)

// 所有组件都将被绘制。

all.draw()组合模式适合应用场景

如果你需要实现树状对象结构, 可以使用组合模式。

组合模式为你提供了两种共享公共接口的基本元素类型: 简单叶节点和复杂容器。 容器中可以包含叶节点和其他容器。 这使得你可以构建树状嵌套递归对象结构。

如果你希望客户端代码以相同方式处理简单和复杂元素, 可以使用该模式。

组合模式中定义的所有元素共用同一个接口。 在这一接口的帮助下, 客户端不必在意其所使用的对象的具体类。

实现方式

-

确保应用的核心模型能够以树状结构表示。 尝试将其分解为简单元素和容器。 记住, 容器必须能够同时包含简单元素和其他容器。

-

声明组件接口及其一系列方法, 这些方法对简单和复杂元素都有意义。

-

创建一个叶节点类表示简单元素。 程序中可以有多个不同的叶节点类。

-

创建一个容器类表示复杂元素。 在该类中, 创建一个数组成员变量来存储对于其子元素的引用。 该数组必须能够同时保存叶节点和容器, 因此请确保将其声明为组合接口类型。

实现组件接口方法时, 记住容器应该将大部分工作交给其子元素来完成。

-

最后, 在容器中定义添加和删除子元素的方法。

记住, 这些操作可在组件接口中声明。 这将会违反接口隔离原则, 因为叶节点类中的这些方法为空。 但是, 这可以让客户端无差别地访问所有元素, 即使是组成树状结构的元素。

组合模式优缺点

- 你可以利用多态和递归机制更方便地使用复杂树结构。

- 开闭原则。 无需更改现有代码, 你就可以在应用中添加新元素, 使其成为对象树的一部分。

- 对于功能差异较大的类, 提供公共接口或许会有困难。 在特定情况下, 你需要过度一般化组件接口, 使其变得令人难以理解。

与其他模式的关系

-

桥接模式、 状态模式和策略模式 (在某种程度上包括适配器模式) 模式的接口非常相似。 实际上, 它们都基于组合模式——即将工作委派给其他对象, 不过也各自解决了不同的问题。 模式并不只是以特定方式组织代码的配方, 你还可以使用它们来和其他开发者讨论模式所解决的问题。

-

你可以在创建复杂组合树时使用生成器模式, 因为这可使其构造步骤以递归的方式运行。

-

责任链模式通常和组合模式结合使用。 在这种情况下, 叶组件接收到请求后, 可以将请求沿包含全体父组件的链一直传递至对象树的底部。

-

你可以使用迭代器模式来遍历组合树。

-

你可以使用访问者模式对整个组合树执行操作。

-

你可以使用享元模式实现组合树的共享叶节点以节省内存。

-

组合和装饰模式的结构图很相似, 因为两者都依赖递归组合来组织无限数量的对象。 装饰类似于组合, 但其只有一个子组件。 此外还有一个明显不同: 装饰为被封装对象添加了额外的职责, 组合仅对其子节点的结果进行了 “求和”。 但是, 模式也可以相互合作: 你可以使用装饰来扩展组合树中特定对象的行为。

-

大量使用组合和装饰的设计通常可从对于原型模式的使用中获益。 你可以通过该模式来复制复杂结构, 而非从零开始重新构造。

代码示例

#include

#include

#include

#include

/**

* The base Component class declares common operations for both simple and

* complex objects of a composition.

*/

class Component {

/**

* @var Component

*/

protected:

Component *parent_;

/**

* Optionally, the base Component can declare an interface for setting and

* accessing a parent of the component in a tree structure. It can also

* provide some default implementation for these methods.

*/

public:

virtual ~Component() {}

void SetParent(Component *parent) {

this->parent_ = parent;

}

Component *GetParent() const {

return this->parent_;

}

/**

* In some cases, it would be beneficial to define the child-management

* operations right in the base Component class. This way, you won't need to

* expose any concrete component classes to the client code, even during the

* object tree assembly. The downside is that these methods will be empty for

* the leaf-level components.

*/

virtual void Add(Component *component) {}

virtual void Remove(Component *component) {}

/**

* You can provide a method that lets the client code figure out whether a

* component can bear children.

*/

virtual bool IsComposite() const {

return false;

}

/**

* The base Component may implement some default behavior or leave it to

* concrete classes (by declaring the method containing the behavior as

* "abstract").

*/

virtual std::string Operation() const = 0;

};

/**

* The Leaf class represents the end objects of a composition. A leaf can't have

* any children.

*

* Usually, it's the Leaf objects that do the actual work, whereas Composite

* objects only delegate to their sub-components.

*/

class Leaf : public Component {

public:

std::string Operation() const override {

return "Leaf";

}

};

/**

* The Composite class represents the complex components that may have children.

* Usually, the Composite objects delegate the actual work to their children and

* then "sum-up" the result.

*/

class Composite : public Component {

/**

* @var \SplObjectStorage

*/

protected:

std::list children_;

public:

/**

* A composite object can add or remove other components (both simple or

* complex) to or from its child list.

*/

void Add(Component *component) override {

this->children_.push_back(component);

component->SetParent(this);

}

/**

* Have in mind that this method removes the pointer to the list but doesn't

* frees the

* memory, you should do it manually or better use smart pointers.

*/

void Remove(Component *component) override {

children_.remove(component);

component->SetParent(nullptr);

}

bool IsComposite() const override {

return true;

}

/**

* The Composite executes its primary logic in a particular way. It traverses

* recursively through all its children, collecting and summing their results.

* Since the composite's children pass these calls to their children and so

* forth, the whole object tree is traversed as a result.

*/

std::string Operation() const override {

std::string result;

for (const Component *c : children_) {

if (c == children_.back()) {

result += c->Operation();

} else {

result += c->Operation() + "+";

}

}

return "Branch(" + result + ")";

}

};

/**

* The client code works with all of the components via the base interface.

*/

void ClientCode(Component *component) {

// ...

std::cout << "RESULT: " << component->Operation();

// ...

}

/**

* Thanks to the fact that the child-management operations are declared in the

* base Component class, the client code can work with any component, simple or

* complex, without depending on their concrete classes.

*/

void ClientCode2(Component *component1, Component *component2) {

// ...

if (component1->IsComposite()) {

component1->Add(component2);

}

std::cout << "RESULT: " << component1->Operation();

// ...

}

/**

* This way the client code can support the simple leaf components...

*/

int main() {

Component *simple = new Leaf;

std::cout << "Client: I've got a simple component:\n";

ClientCode(simple);

std::cout << "\n\n";

/**

* ...as well as the complex composites.

*/

Component *tree = new Composite;

Component *branch1 = new Composite;

Component *leaf_1 = new Leaf;

Component *leaf_2 = new Leaf;

Component *leaf_3 = new Leaf;

branch1->Add(leaf_1);

branch1->Add(leaf_2);

Component *branch2 = new Composite;

branch2->Add(leaf_3);

tree->Add(branch1);

tree->Add(branch2);

std::cout << "Client: Now I've got a composite tree:\n";

ClientCode(tree);

std::cout << "\n\n";

std::cout << "Client: I don't need to check the components classes even when managing the tree:\n";

ClientCode2(tree, simple);

std::cout << "\n";

delete simple;

delete tree;

delete branch1;

delete branch2;

delete leaf_1;

delete leaf_2;

delete leaf_3;

return 0;

}

执行结果

Client: I've got a simple component: RESULT: Leaf Client: Now I've got a composite tree: RESULT: Branch(Branch(Leaf+Leaf)+Branch(Leaf)) Client: I don't need to check the components classes even when managing the tree: RESULT: Branch(Branch(Leaf+Leaf)+Branch(Leaf)+Leaf)