States of Integrity Constraints

States of Integrity Constraints

As part of constraint definition, you can specify how and when Oracle Database should enforce the constraint, thereby determining the constraint state.

Checks for Modified and Existing Data

The database enables you to specify whether a constraint applies to existing data or future data. If a constraint is enabled, then the database checks new data as it is entered or updated. Data that does not conform to the constraint cannot enter the database. For example, enabling a NOT NULL constraint on employees.department_id guarantees that every future row has a department ID. If a constraint is disabled, then the table can contain rows that violate the constraint.

You can set constraints to validate (VALIDATE) or not validate (NOVALIDATE) existing data. If VALIDATE is specified, then existing data must conform to the constraint. For example, enabling a NOT NULL constraint on employees.department_id and setting it to VALIDATE checks that every existing row has a department ID. If NOVALIDATE is specified, then existing data need not conform to the constraint.

The behavior of VALIDATE and NOVALIDATE always depends on whether the constraint is enabled or disabled. Table 5-4 summarizes the relationships.

Table 5-4 Checks on Modified and Existing Data

| Modified Data | Existing Data | Summary |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Existing and future data must obey the constraint. An attempt to apply a new constraint to a populated table results in an error if existing rows violate the constraint. |

|

|

|

The database checks the constraint, but it need not be true for all rows. Thus, existing rows can violate the constraint, but new or modified rows must conform to the rules. |

|

|

|

The database disables the constraint, drops its index, and prevents modification of the constrained columns. |

|

|

|

The constraint is not checked and is not necessarily true. |

See Also:

Oracle Database SQL Language Reference to learn about constraint statesDeferrable Constraints

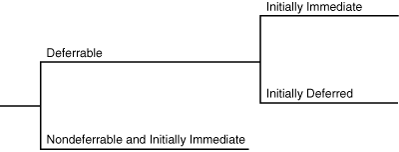

Every constraint is either in a not deferrable (default) or deferrable state. This state determines when Oracle Database checks the constraint for validity. The following graphic depicts the options for deferrable constraints.

Description of the illustration cncpt313.gif

Nondeferrable Constraints

If a constraint is not deferrable, then Oracle Database never defers the validity check of the constraint to the end of the transaction. Instead, the database checks the constraint at the end of each statement. If the constraint is violated, then the statement rolls back.

For example, assume that you create a nondeferrable NOT NULL constraint for the employees.last_name column. If a user attempts to insert a row with no last name, then the database immediately rolls back the statement because the NOT NULL constraint is violated. No row is inserted.

Deferrable Constraints

A deferrable constraint permits a transaction to use the SET CONSTRAINT clause to defer checking of this constraint until a COMMIT statement is issued. If you make changes to the database that might violate the constraint, then this setting effectively lets you disable the constraint until all the changes are complete.

You can set the default behavior for when the database checks the deferrable constraint. You can specify either of the following attributes:

-

INITIALLY IMMEDIATEThe database checks the constraint immediately after each statement executes. If the constraint is violated, then the database rolls back the statement.

-

INITIALLY DEFERREDThe database checks the constraint when a

COMMITis issued. If the constraint is violated, then the database rolls back the transaction.

Assume that a deferrable NOT NULL constraint on employees.last_name is set to INITIALLY DEFERRED. A user creates a transaction with 100 INSERT statements, some of which have null values for last_name. When the user attempts to commit, the database rolls back all 100 statements. However, if this constraint were set to INITIALLY IMMEDIATE, then the database would not roll back the transaction.

If a constraint causes an action, then the database considers this action as part of the statement that caused it, whether the constraint is deferred or immediate. For example, deleting a row in departments causes the deletion of all rows in employees that reference the deleted department row. In this case, the deletion from employees is considered part of the DELETE statement executed against departments.

See Also:

Oracle Database SQL Language Reference for information about constraint attributes and their default valuesExamples of Constraint Checking

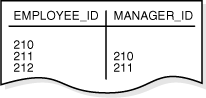

Some examples may help illustrate when Oracle Database performs the checking of constraints. Assume the following:

-

The

employeestable has the structure shown in Figure 5-2. -

The self-referential constraint makes entries in the

manager_idcolumn dependent on the values of theemployee_idcolumn.

Insertion of a Value in a Foreign Key Column When No Parent Key Value Exists

Consider the insertion of the first row into the employees table. No rows currently exist, so how can a row be entered if the value in the manager_id column cannot reference any existing value in the employee_id column? Some possibilities are:

-

A null can be entered for the

manager_idcolumn of the first row, if themanager_idcolumn does not have aNOTNULLconstraint defined on it.Because nulls are allowed in foreign keys, this row is inserted into the table.

-

The same value can be entered in the

employee_idandmanager_idcolumns, specifying that the employee is his or her own manager.This case reveals that Oracle Database performs its constraint checking after the statement has been completely run. To allow a row to be entered with the same values in the parent key and the foreign key, the database must first run the statement (that is, insert the new row) and then determine whether any row in the table has an

employee_idthat corresponds to themanager_idof the new row. -

A multiple row

INSERTstatement, such as anINSERTstatement with nestedSELECTstatement, can insert rows that reference one another.For example, the first row might have 200 for employee ID and 300 for manager ID, while the second row has 300 for employee ID and 200 for manager. Constraint checking is deferred until the complete execution of the statement. All rows are inserted first, and then all rows are checked for constraint violations.

Default values are included as part of an INSERT statement before the statement is parsed. Thus, default column values are subject to all integrity constraint checking.

An Update of All Foreign Key and Parent Key Values

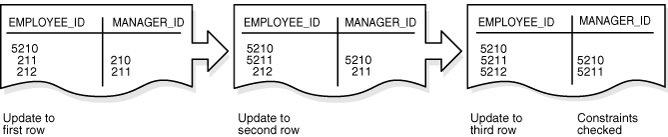

Consider the same self-referential integrity constraint in a different scenario. The company has been sold. Because of this sale, all employee numbers must be updated to be the current value plus 5000 to coordinate with the employee numbers of the new company. Because manager numbers are really employee numbers (see Figure 5-3), the manager numbers must also increase by 5000.

Figure 5-3 The employees Table Before Updates

Description of "Figure 5-3 The employees Table Before Updates"

You could execute the following SQL statement to update the values:

UPDATE employees SET employee_id = employee_id + 5000, manager_id = manager_id + 5000;

Although a constraint is defined to verify that each manager_id value matches an employee_id value, the preceding statement is legal because the database effectively checks constraints after the statement completes. Figure 5-4 shows that the database performs the actions of the entire SQL statement before checking constraints.

The examples in this section illustrate the constraint checking mechanism during INSERT and UPDATE statements, but the database uses the same mechanism for all types of DML statements. The same mechanism is used for all types of constraints, not just self-referential constraints.

Note:

Operations on a view or synonym are subject to the integrity constraints defined on the base tables.