Hive 数据类型 文件格式

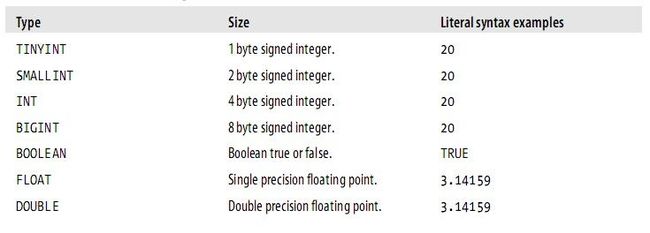

Primitive Data Types --Hive 支持数据类型

Hive supports several sizes of integer and floating-point types, a Boolean type, and

character strings of arbitrary length. Hive v0.8.0 added types for timestamps and binary

fields.

What if you run a query that wants to interpret a string column as a number? You can

explicitly cast one type to another as in the following example, where s is a string

column that holds a value representing an integer:

... cast(s AS INT) ...;

(To be clear, the AS INT are keywords, so lowercase would be fine.)

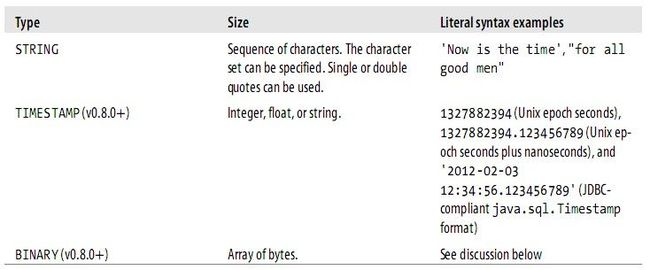

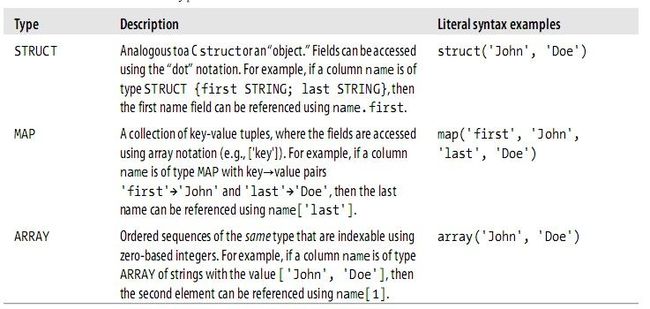

Collection Data Types -- 特殊数据类型

Hive supports columns that are structs, maps, and arrays.

Here is a table declaration that demonstrates how to use these types, an employees table

in a fictitious Human Resources application:

CREATE TABLE employees ( name STRING, salary FLOAT, subordinates ARRAY<STRING>, deductions MAP<STRING, FLOAT>, address STRUCT<street:STRING, city:STRING, state:STRING, zip:INT>);

Text File Encoding of Data Values -- 文本文件编码

Let’s begin our exploration of file formats by looking at the simplest example, text files.

You are no doubt familiar with text files delimited with commas or tabs, the so-called

comma-separated values (CSVs) or tab-separated values (TSVs), respectively. Hive can

use those formats if you want and we’ll show you how shortly. However, there is a

drawback to both formats; you have to be careful about commas or tabs embedded in

text and not intended as field or column delimiters. For this reason, Hive uses various

control characters by default, which are less likely to appear in value strings. Hive uses

the term field when overriding the default delimiter, as we’ll see shortly.

Taxes^C.05^BInsurance^C.1^A1 Michigan Ave.^BChicago^BIL^B60600

Mary Smith^A80000.0^ABill King^AFederal Taxes^C.2^BState Taxes^C.

05^BInsurance^C.1^A100 Ontario St.^BChicago^BIL^B60601

Todd Jones^A70000.0^AFederal Taxes^C.15^BState Taxes^C.03^BInsurance^C.

1^A200 Chicago Ave.^BOak Park^BIL^B60700

Bill King^A60000.0^AFederal Taxes^C.15^BState Taxes^C.03^BInsurance^C.

1^A300 Obscure Dr.^BObscuria^BIL^B60100

This is a little hard to read, but you would normally let Hive do that for you, of course.

Let’s walk through the first line to understand the structure. First, here is what it would

look like in JavaScript Object Notation (JSON), where we have also inserted the names

from the table schema:

{

"name": "John Doe",

"salary": 100000.0,

"subordinates": ["Mary Smith", "Todd Jones"],

"deductions": {

"Federal Taxes": .2,

"State Taxes": .05,

"Insurance": .1

},

"address": {

"street": "1 Michigan Ave.",

"city": "Chicago",

"state": "IL",

"zip": 60600

}

}

You’ll note that maps and structs are effectively the same thing in JSON.

Now, here’s how the first line of the text file breaks down:

• John Doe is the name.

• 100000.0 is the salary.

• Mary Smith^BTodd Jones are the subordinates “Mary Smith” and “Todd Jones.”

• Federal Taxes^C.2^BState Taxes^C.05^BInsurance^C.1 are the deductions, where

20% is deducted for “Federal Taxes,” 5% is deducted for “State Taxes,” and 10%

is deducted for “Insurance.”

• 1 Michigan Ave.^BChicago^BIL^B60600 is the address, “1 Michigan Ave., Chicago,

60600.”

You can override these default delimiters. This might be necessary if another applica-

tion writes the data using a different convention. Here is the same table declaration

again, this time with all the format defaults explicitly specified:

CREATE TABLE employees ( name STRING, salary FLOAT, subordinates ARRAY<STRING>, deductions MAP<STRING, FLOAT>, address STRUCT<street:STRING, city:STRING, state:STRING, zip:INT> ) ROW FORMAT DELIMITED FIELDS TERMINATED BY '\001' COLLECTION ITEMS TERMINATED BY '\002' MAP KEYS TERMINATED BY '\003' LINES TERMINATED BY '\n' STORED AS TEXTFILE;