From the day garments became part of people’s lives, they have been given different significance of social status, lifestyle, aesthetics and cultural concepts. Clothing has always been the truest and most straightforward reflection of the social and historical scenes of any given time. In this sense, the history of clothing is at the same time a vivid history of the development of civilization. (Chinese Clothing )

In the Chinese way of describing the necessities of life, clothing ranks at the top of “clothing, food, shelter, and means of travel.” In this country with a long history of garments and ornaments, there is a wealth of archeological findings showing the development of garments, as well as their portrayals in ancient mythology, history books, poems and songs, novels and drama.

The development of Chinese garments can be traced back to the late Paleolithic age. Archeological findings have shown that approximately 20,000 years ago, the primitives who lived in the now Zhoukoudian area of Beijing were already wearing personal ornaments, in the form of tiny white stone beads, olive-colored pebbles, animal teeth, clam shells, fish bones and bone tubes, all meticulously perforated. Archeologists have attributed these to be body ornaments. Aesthetics might not have been the only concern when people wore ornaments at that time — ornaments were used as a means of protection against evil. The unearthed bone needles were still intact with oval shaped needle hole, a sign that people at that time were no longer satisfied with utilizing animal and plant materials. They already learned the technology of sewing together animal skin.

Over 1,000 archeological sites of the Neolithic age (6,000 B.C.-2,000 B.C.) have been found in China, geographically covering almost the entire country. The major means of production have transformed from the primitive hunting and fishing to the more stable form of agriculture, while the division of labor first appeared in weaving and pottery making. Ancient painted pottery pots from 5,000 years ago were found in Qinghai Province of western China, decorated with dancers imitating the hunting scene. Some dancers wear decorative braids on their heads, while others have ornamental tails on the waist. Some wear full skirts that are rarely seen in traditional Chinese attire, but more similar to the whalebone skirt of the western world. In the neighboring province of Gansu, similar vessels were excavated, with images of people wearing what the later researchers called the “Guankoushan,” a typical style found in the early human garments: a piece of textile with a slit or hole in the middle from which the head comes through.

A rope is tied at the waist, giving the garment a dress-like appearance. Another vessel portrays an image of an attractive young girl, with short bangs on the forehead and long hair in the back. Against the delicate facial features and below the neck a continuous pattern is found with three rows of slanting lines and triangles. It may well have been a lively young girl in a beautiful dress with intricate patterns on the mind of the pottery maker. In addition to the clay vessels, images of primitive Chinese garments were found in rock paintings of the early people wearing ear ornaments. In the Daxi Neolithic site of Wushan, Sichuan, historical artifacts were found including ear ornaments made of jade, ivory, and turquoise in the round, oblong, trapezoid and even semi-circle shapes.

Along with the establishment of the different social strata, rituals distinguishing the respectable from the humble came into being, leading eventually to the formation of rules and regulations on daily attire. The Chinese rules on garments and ornaments started taking shape in the Zhou Dynasty (1,046 B.C.-256 B.C.), regulating the royalty down to the commoners, and these were recorded in the national decrees and regulations. As early as in the Zhou Dynasty, garments were already classified into sacrificial attire, court attire, army uniform, mourning attire, and wedding attire. This tradition was once broken during the Spring and Autumn Period (770 B.C.-476 B.C.) and the Warring States Period (475 B.C.-221 B.C.), in which numerous warlords fought for power and a hundred schools of thoughts contended. As a result, rigid rules on garments and ornaments were replaced by a diversity of style, and the aristocratic class went after extravagance.

The rulers of the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) used the Zhou Li — book on Zhou Dynasty Rituals as the blueprint and promulgated categorical rules on garments and ornaments. Dress colors were specified into spring green, summer red, autumn yellow and winter black to be in harmony with the seasons and the solar calendar, all in a style of sober simplicity. Women’s upper and lower garments became the model for the Han ethnicity of later generations.

The Wei, Jin and Southern and Northern Dynasties (220–589) was a period of ethnic amalgamation with, despite the frequent change in power and incessant wars, ideological diversity, cultural prosperity, and significant scientific development. In this period, there was not only the Wei and Jin aristocratic style that the intelligentsia took delight in talking about, but also the shocks and transformations on the traditional Han culture brought about by the northern nomadic tribes when they migrated into the central plains. These ethnic minority people settled down with the Han people. As a result, the way they dressed influenced the Han style, while at the same time it was influenced by the Han style.

When China was reunited in the Sui Dynasty (581- 618), the Han dress code was pursued again. In the Tang Dynasty (618–907) that followed, the strong national power and an open social order led to a flourishing of garment and ornament style that is both luxuriant and refreshing, typically with women wearing low cut short shirtdress or narrow-sleeved men’s attire. By Song Dynasty (960–1279), the Han women developed the habit of chest- binding, giving popularity to the popular overcoat Beizi, whose elegant and simplistic style was favored by women of all ages and all social strata. Yuan Dynasty (1206–1368) was established by the Mongols when they unified China. As Mongols at that time wore Maoli or triangular hat, and men commonly wore earrings, the official dress code became a mixture of the inherited Han system with the Mongol elements. When power again changed hands to the Han people, the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) rulers promulgated decrees prohibiting the use of the previous dynasty’s Mongol attire, language, and surnames, returning to the dress style of the Tang Dynasty. The official uniform of the Ming Dynasty was intent on seeking a sense of dignity and splendor, as shown in the complex forms, styles and dressing rituals of the emperor down to officials of all levels.

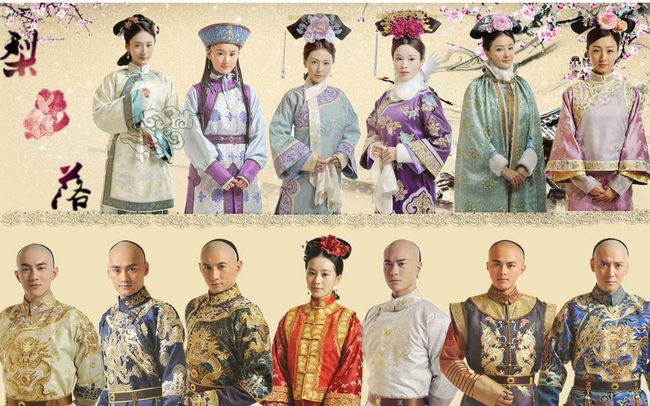

More than 200 years of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) was a period with the most significant changes in garment style. The Manchu dress style which the rulers tried to force on the Han people was met with strong resistance, but a later compromise by the government led to a silent fusion of the two dress styles. The long mandarin gown (Changpao) and jacket (Magua) style have become the quintessential Qing style whenever the topic of Qing dress is brought up.

After 1840, China entered the contemporary era. Seaport cities, especially metropolis like Shanghai, led the change towards western-style under the influence of the European and American fashion trends. Industrialization in the textile weaving and dying in the west brought about the import of low-cost materials, gradually replacing domestic materials made traditionally. Intricately made and trendy ready-to-wear garments in western style also found their way into the Chinese market, gaining the upper hand over the time-consuming traditional techniques of hand rolling, bordering, inlay and embroidery with its large scale machine operated dress-making.

Looking in retrospect at Chinese garments of the 20th century, we see an array of styles of Qipao, Cheongsam, the Sun Yat-sen’s uniform, student uniform, western suits, hat, silk stockings, high heels, workers’ uniform, Lenin jacket, the Russian dress, army style, jacket, bell-bottoms, miniskirts, bikinis, professional attire, punk style and T-shirt, all witnessing the days gone by… The qipao dress, now regarded as the typical Chinese dress style, only became popular in the 1920s. Originating in the Manchu women’s dress, incorporating techniques of the Han ladies’ garments and absorbing styles of the 20th century western dresses, it has now evolved into a major fashion element to be reckoned with in the international fashion industry.

China, as a country made up of 56 ethnic groups that continually influenced each other, has undergone a continuous transformation in dress style and customs. The distinction not only existed among dynasties but also quite pronounced even in different periods within the same dynasty. The overall characteristics of the Chinese garments can be summarized as bright colors, refined artisanship, and ornate details.

Diversity in style can be seen among different ethnic groups, living environments, local customs, lifestyles, and aesthetic tastes. Chinese folk garments are deeply rooted in the daily life and folk activities of the common people, full of rustic flavor and exuberant with vitality. Many of the folk dresses are still popular today, for example, the red velvet flower hairpiece, the embroidered keepsakes between lovers, coil hats and raincoats made of natural fiber, not to mention the handmade tiger hats, tiger shoes, pig shoes, cat shoes, and the child buttock shields.

The progress of modernization is effacing the ethnic characters of the urban dress style. However in the vast rural areas, especially in areas with a high concentration of ethnic minority people, a wide array of beautiful garments and ornaments are still part of the local lifestyle, offering a unique folk scene together with the local landscape.