作者:Andrew S. Grove

出版社:Profile Business

发行时间:May 5th 2010 by Crown Business (first published April 1st 1988)

来源:下载的 epub 版本

Goodreads:3.95(4657 Ratings)

豆瓣:7.5(3000人评价)

概要

Grove reveals his strategy of focusing on a new way of measuring the nightmare moment every leader dreads -- when massive change occurs and a company must, virtually overnight, adapt or fall by the wayside.

作者介绍

Andrew Stephen 'Andy' Grove (born András István Gróf; 2 September 1936 – 21 March 2016) was a Hungarian-born American businessman, engineer, author and a pioneer in the semiconductor industry. He escaped from Communist-controlled Hungary at the age of 20 and moved to the United States where he finished his education. He was one of the founders and the CEO of Intel, helping transform the company into the world's largest manufacturer of semiconductors.

As a result of his work at Intel, along with his books and professional articles, Grove had a considerable influence on electronics manufacturing industries worldwide. He has been called the "guy who drove the growth phase" of Silicon Valley. In 1997, Time magazine chose him as "Man of the Year", for being "the person most responsible for the amazing growth in the power and the innovative potential of microchips." One source notes that by his accomplishments at Intel alone, he "merits a place alongside the great business leaders of the 20th century."

读后感

读这本书,一方面是因为乔布斯的推荐,另一方面是因为书名,了解一下为什么「只有偏执狂才能生存」,但是其实全书和这个书名没有多少关系,作者把书名起成这样,完全是出于任性:

I’m often credited with the motto, “Only the paranoid survive.” I have no idea when I first said this, but the fact remains that, when it comes to business, I believe in the value of paranoia. Business success contains the seeds of its own destruction.

全书围绕作者提出的「策略转折点(strategic inflection points)」这个概念展开,我觉得作者这么任性的用一本书去阐述这个其实并不是那么困难的概念,真的是有点杀鸡用牛刀,但是感觉这个概念并没有在后来获得足够的影响力,我觉得这个概念被后来的「破坏性创新」替代了

全书最大的亮点,是作者作为 Intel 联合创始人,一路发展的心路历程,这也是本书最大的看点,虽然本书的写作已经有30年了,但是对于现在的企业管理者而言,依然有非常「严肃」的意义,绝对不可轻视

摘录

But in capitalist reality, as distinguished from its textbook picture, it is not (price) competition which counts but the competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the source of supply, the new type of organization … competition which … strikes not at the margins … of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.

—Joseph A. Schumpeter,

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, 1942

Sooner or later something fundamental in your business world will change.

I’m often credited with the motto, “Only the paranoid survive.” I have no idea when I first said this, but the fact remains that, when it comes to business, I believe in the value of paranoia. Business success contains the seeds of its own destruction. The more successful you are, the more people want a chunk of your business and then another chunk and then another until there is nothing left. I believe that the prime responsibility of a manager is to guard constantly against other people’s attacks and to inculcate this guardian attitude in the people under his or her management.

The things I tend to be paranoid about vary. I worry about products getting screwed up, and I worry about products getting introduced prematurely. I worry about factories not performing well, and I worry about having too many factories. I worry about hiring the right people, and I worry about morale slacking off.

And, of course, I worry about competitors. I worry about other people figuring out how to do what we do better or cheaper, and displacing us with our customers.

But these worries pale in comparison to how I feel about what I call strategic inflection points.

I’ll describe what a strategic inflection point is a bit later in this book. For now, let me just say that a strategic inflection point is a time in the life of a business when its fundamentals are about to change. That change can mean an opportunity to rise to new heights. But it may just as likely signal the beginning of the end.

Strategie inflection points can be caused by technological change but they are more than technological change. They can be caused by competitors but they are more than just competition. They are full-scale changes in the way business is conducted, so that simply adopting new technology or fighting the competition as you used to may be insufficient. They build up force so insidiously that you may have a hard time even putting a finger on what has changed, yet you know that something has.

Let’s not mince words: A strategic inflection point can be deadly when unattended to. Companies that begin a decline as a result of its changes rarely recover their previous greatness.

We live in an age in which the pace of technological change is pulsating ever faster, causing waves that spread outward toward all industries. This increased rate of change will have an impact on you, no matter what you do for a living. It will bring new competition from new ways of doing things, from corners that you don’t expect.

The sad news is, nobody owes you a career. Your career is literally your business. You own it as a sole proprietor. You have one employee: yourself. You are in competition with millions of similar businesses: millions of other employees all over the world. You need to accept ownership of your career, your skills and the timing of your moves. It is your responsibility to protect this personal business of yours from harm and to position it to benefit from the changes in the environment. Nobody else can do that for you.

I teach a class strategic management at Stanford University’s business school as a part-time departure from my job as president and CEO of Intel Corporation. The way my co-teacher, Professor Robert Burgelman, and I normally grade the students is to go through the class roster right after each session and assess each student’s class performance while it is still fresh in our memories.

The process was taking a little longer than usual on the morning of November 22, 1994, the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, and I was about to excuse myself to call my office when the phone rang. It was my office calling me. Our head of communications wanted to talk to me—urgently. She wanted to let me know that a CNN crew was coming to Intel. They had heard of the floating point flaw in the Pentium processor and the story was about to blow up.

I have to backtrack here. First, a word about Intel. Intel in 1994 was a $10 billion-plus producer of computer chips, the largest in the world. We were twenty-six years old and in that period of time we had pioneered two of the most important building blocks of modern technology, memory chips and microprocessors. In 1994, most of our business revolved around microprocessors and it revolved very well indeed. We were very profitable, growing at around 30 percent per year.

Nineteen ninety-four was a very special year for us in another way. It was the year in which we were ramping our latest-generation microprocessor, the Pentium processor, into full-scale production. This was a very major undertaking involving hundreds of our direct customers, i.e., computer manufacturers, some of whom enthusiastically endorsed the new technology and some of whom didn’t. We were fully committed to it, so we were heavily advertising the product to get the attention of computer buyers. Internally, we geared up manufacturing plants at four different sites around the world. This project was called “Job 1” so all our employees knew where our priorities lay.

In the context of all this, a troubling event happened. Several weeks earlier, some of our employees had found a string of comments on the Internet forum where people interested in Intel products congregate. The comments were under headings like, “Bug in the Pentium FPU.” (FPU stands for floating point unit, the part of the chip that does the heavy-duty math.) They were triggered by the observation of a math professor that something wasn’t quite right with the mathematical capabilities of the Pentium chip. This professor reported that he had encountered a division error while studying some complex math problems.

We were already familiar with this problem, having encountered it several months earlier. It was due to a minor design error on the chip, which caused a rounding error in division once every nine billion times. At first, we were very concerned about this, so we mounted a major study to try to understand what once every nine billion divisions would mean. We found the results reassuring. For instance, they meant that an average spreadsheet user would run into the problem only once every 27,000 years of spreadsheet use. This is a long time, much longer than it would take for other types of problems which are always encountered in semiconductors to trip up a chip. So while we created and tested ways to correct the defect, we went about our business.

Meanwhile, this Internet discussion came to the attention of the trade press and was described thoroughly and accurately in afront-page article in one of the trade weeklies. The next week it was picked up as a smaller item in other trade papers. And that seemed to be it. That is, until that Tuesday morning before Thanksgiving.

That’s when CNN showed up wanting to talk to us, and they seemed all fired up. The producer had opened his preliminary discussion with our public relations people in an aggressive and accusatory tone. As I listened to our head of communications on the phone, it didn’t sound good. I picked up my papers and headed back to the office. In fact, it wasn’t good. CNN produced a very unpleasant piece, which aired the next day.

In the days after that, every major newspaper started reporting on the story with headlines ranging from “Flaw Undermines Accuracy of Pentium Chips” to “The Pentium Proposition: To Buy or Not to Buy.” Television reporters camped outside our headquarters. The Internet message traffic skyrocketed. It seemed that everyone in the United States keyed into this, followed shortly by countries around the world.

Users started to call us asking for replacement chips. Our replacement policy was based on our assessment of the problem. People whose use pattern suggested that they might do a lot of divisions got their chips replaced. Other users we tried to reassure by walking them through our studies and our analyses, offering to send them a white paper that we wrote on this subject. After the first week or so, this dual approach seemed to be working reasonably well. The daily call volumes were decreasing, we were gearing up to refine our replacement procedures and, although the press was still pillorying us, all tangible indicators—from computer sales to replacement requests—showed that we were managing to work our way through this problem.

Then came Monday, December 12. I walked into my office at eight o’clock that morning and in the little clip where my assistant leaves phone messages there was a folded computer printout. Itwas a wire service report. And as often happens with breaking news it consisted only of the title. It said something to this effect: IBM stops shipments of all Pentium-based computers.

All hell broke loose again. IBM’s action was significant because, well, they are IBM. Although in recent years IBM has not been the power they once were in the PC business, they did originate the “IBM PC” and by choosing to base it on Intel’s technology, they made Intel’s microprocessors preeminent. For most of the thirteen years since the PC’s inception, IBM has been the most important player in the industry. So their action got a lot of attention.

The phones started ringing furiously from all quarters. The call volume to our hotline skyrocketed. Our other customers wanted to know what was going on. And their tone, which had been quite constructive the week before, became confused and anxious. We were back on the defensive again in a major way.

A lot of the people involved in handling this stuff had only joined Intel in the last ten years or so, during which time our business had grown steadily. Their experience had been that working hard, putting one foot in front of the other, was what it took to get a good outcome. Now, all of a sudden, instead of predictable success, nothing was predictable. Our people, while they were busting their butts, were also perturbed and even scared.

And there was another dimension to this problem. It didn’t stop at the doors of Intel. When they went home, our employees had to face their friends and their families, who gave them strange looks, sort of accusing, sort of wondering, sort of like, “What are you all doing? I saw such and such on TV and they said your company is greedy and arrogant.” Our employees were used to hearing nothing but positive remarks when they said that they worked at Intel. Now they were hearing deprecating jokes like, “What do you get when you cross a mathematician with a Pentium? A mad scientist.” And you couldn’t get away from it. At every family dinner, at every holiday party, this was the subject of discussion. This change was hard on them, and it scarcely helped their spirits when they had to go back the next morning to answer telephone hotlines, turn production lines on their heads and the like.

I wasn’t having a wonderful time either. I’ve been around this industry for thirty years and at Intel since its inception, and I have survived some very difficult business situations, but this was different. It was much harsher than the others. In fact, it was unlike any of the others at every step. It was unfamiliar and rough territory. I worked hard during the day but when I headed home I got instantly depressed. I felt we were under siege—under unrelenting bombardment. Why was this happening?!

Conference room 528, which is located twenty feet from my office, became the Intel war room. The oval table there is meant to seat about twelve people, but at several times each day more than thirty people were jammed in the room, sitting on the credenza, standing against the wall, coming and going, bringing missives from the front and leaving to execute agreed-upon courses of action.

After a number of days of struggling against the tide of public opinion, of dealing with the phone calls and the abusive editorials, it became clear that we had to make a major change.

The next Monday, December 19, we changed our policy completely. We decided to replace anybody’s part who wanted it replaced, whether they were doing statistical analysis or playing computer games. This was no minor decision. We had shipped millions of these chips by now and none of us could even guess how many of them would come back—maybe just a few, or maybe all of them.

In a matter of days, we built up a major organization practically from scratch to answer the flood of phone calls. We had not been in the consumer business in any big way before, so dealing with consumer questions was not something we had ever had to do.Now, suddenly, we did from one day to another and on a fairly major scale. Our staffing first came from volunteers, from people who worked in different areas of Intel—designers, marketing people, software engineers. They all dropped what they were doing, sat at makeshift desks, answered phones and took down names and addresses. We began to systematically oversee the business of replacing people’s chips by the hundreds of thousands. We developed a logistics system to track these hundreds of thousands of chips coming and going. We created a service network to handle the physical replacement for people who didn’t want to do it themselves.

Back in the summer when we had first found the floating point flaw, we had corrected the chip design, checked it out very thoroughly to make sure the change didn’t produce any new problems, and had already started to phase the corrected version into manufacturing by the time these events took place. We now accelerated this conversion by canceling the usual Christmas shutdown in our factories, and speeded things up even further by pulling the old material off the line and junking it all.

Ultimately, we took a huge write-off—to the tune of $475 million. The write-off consisted of the estimates of the replacement parts plus the value of the materials we pulled off the line. It was the equivalent of half a year’s R&D budget or five years’ worth of the Pentium processor’s advertising spending.

And we embarked on a whole new way of doing business.

In the three months following the Pentium floating point incident, Microsoft’s new operating system, Windows 95, was delayed; Apple delayed the release of their new software, Copland; long-standing bugs in both the Windows calculator and Word for Macintosh were highlighted with substantial publicity in trade newspapers; and difficulties associated with Disney’s Lion King CD-ROM game and Intuit’s tax programs all became subjects of daily newspaper coverage. Something changed, not just for Intel but for others in the high-tech business as well.

I don’t think this kind of change is a high-tech phenomenon. Examples from industries of all different kinds stare at me from daily newspapers. All the turbulent actions of investments, takeovers and write-offs in the media and telecommunications companies, as well as in banking and healthcare, seem to point to industries in which “something has changed.” Technology has something to do with most of these changes only because technology gives companies in each of these industries the power to alter the order around them.

If you work in one of these industries and you are in middle management, you may very well sense the shifting winds on your face before the company as a whole and sometimes before your senior management does. Middle managers—especially those who deal with the outside world, like people in sales—are often the first to realize that what worked before doesn’t quite work anymore; that the rules are changing. They usually don’t have an easy time explaining it to senior management, so the senior management in a company is sometimes late to realize that the world is changing on them—and the leader is often the last of all to know.

Here’s an example: I recently listened to evaluations of a certain highly touted new software from a company whose other products we already use. Our head of Information Technology told of unanticipated obstacles we were running into by trying to adopt this new software and therefore said that she was inclined to wait until the following generation of software was ready. Our marketing manager had heard of the same situation at other companies as well.

I called up the software company’s CEO to tell him what I was hearing and asked, “Are you considering changing your strategy and going directly to the new generation?” He said, “No way.” They were going to stay the course, they had heard of no one having any problems with their strategy.

When I reported this to the individuals who brought me the news, our IT manager said, “Well, that guy is always the last to know.” He, like most CEOs, is in the center of a fortified palace, and news from the outside has to percolate through layers of people from the periphery where the action is. Our IT manager isthe periphery. Our marketing manager also experiences the skirmishes there.

I was one of the last to understand the implications of the Pentium crisis. It took a barrage of relentless criticism to make me realize that something had changed—and that we needed to adapt to the new environment. We could change our ways and embrace the fact that we had become a household name and a consumer giant, or we could keep our old ways and not only miss an opportunity to nurture new customer relationships but also suffer damage to our corporate reputation and well-being.

The lesson is, we all need to expose ourselves to the winds of change. We need to expose ourselves to our customers, both the ones who are staying with us as well as those that we may lose by sticking to the past. We need to expose ourselves to lower-level employees, who, when encouraged, will tell us a lot that we need to know. We must invite comments even from people whose job it is to constantly evaluate and critique us, such as journalists and members of the financial community. Turn the tables and ask them some questions: about competitors, trends in the industry and what they think we should be most concerned with. As we throw ourselves into raw action, our senses and instincts will rapidly be honed again.

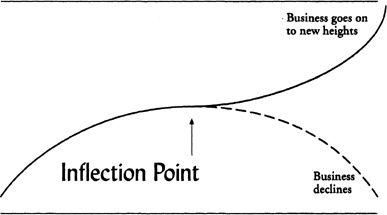

What is an inflection point? Mathematically, we encounter an inflection point when the rate of change of the slope of the curve (referred to as its “second derivative”) changes sign, for instance, going from negative to positive. In physical terms, it’s where a curve changes from convex to concave, or vice versa. As shown in the diagram, it’s the point at which a curve stops curving one way and starts curving the other way.

So it is with strategic business matters, too. An inflection point occurs where the old strategic picture dissolves and gives way tothe new, allowing the business to ascend to new heights. However, if you don’t navigate your way through an inflection point, you go through a peak and after the peak the business declines. It is around such inflection points that managers puzzle and observe, “Things are different. Something has changed.”

The arguments in the midst of an inflection point can be ferocious. “If our product worked a little better or it cost a little less, we would have no problems,” one person will say. And he’s probably partially right. “It’s just a downturn in the economy. Once capital spending rebounds, we’ll resume our growth,” another will say. And he’s probably partially right. Yet another person comes back from a trade show confused and perturbed, and says, “The industry has gone nuts. It’s crazy what people use computers for today.” He hardly gets a lot of serious attention.

So how do we know that a set of circumstances is a strategic inflection point?

Most of the time, recognition takes place in stages.

First, there is a troubling sense that something is different. Things don’t work the way they used to. Customers’ attitudes toward you are different. The development groups that have had a history of successes no longer seem to be able to come up with the right product. Competitors that you wrote off or hardly knew existed are stealing business from you. The trade shows seem weird.

Then there is a growing dissonance between what your company thinks it is doing and what is actually happening inside the bowels of the organization. Such misalignment between corporate statements and operational actions hints at more than the normal chaos that you have learned to live with.

Eventually, a new framework, a new set of understandings, a new set of actions emerges. It’s as if the group that was lost finds its bearings again. (This could take a year—or a decade.) Last of all, a new set of corporate statements is generated, often by a new set of senior managers.

单词列表:

| words | sentence |

|---|---|

| in vivo | The first represents a kind of in vivo lesson about managing change |

| in vitro | the second, its in vitro counterpart |

| moat | But every day, technology narrows that moat inch by inch |

| mammoth | companies we used to consider mammoth and gigantic compared to us just a few years ago |

| gingerly | turbulent rapids that even professional rafters approach gingerly |

| tsunami | There’s wind and then there’s a typhoon, there are waves and then there’s a tsunami |

| equilibrium | Eventually, a new equilibrium in the industry will be reached |