作者:Gary Sernovitz

出版社:St. Martin's Press

副标题:The Complete Story of the Shale Revolution, the Fight over Fracking, and the Future of Energy

发行时间:2016年2月23日

来源:下载的 epub 版本

Goodreads:4.14(22 Ratings)

豆瓣:无

概要

全书通过五个不同的视角(产业发展、地域、财政、全球、国家),介绍了最近20年席卷全球的「页岩油革命」的发展历程,作者在开篇介绍了自己撰写本书的使命:

This book’s mission is to explain the shale revolution, and its ambiguities, to allow us to make the best available decisions, ones beyond and more precise than either-or. To do so, we must start first with a total understanding, to know the green and the black, all the realities and possibilities of this once unimaginable shift. This is a book about where we have shockingly, excitingly, frighteningly found ourselves. Where we go from here, well, that’s up to us.

作者介绍

作者 Gary Sernovitz 曾经在高盛做能源产业的咨询研究,做了3年觉得这个行业已经走向枯竭所以离职开始做自由撰稿人,因为作者的视角一直没有离开能源行业,所以本书的含金量是可以的

Gary Sernovitz is a managing director at Lime Rock, an oil- and gas-focused private equity firm. He began his career as an oil equity research analyst at Goldman Sachs. He is a graduate of Cornell University.

个人观点

「页岩油革命」的发展历程中,环保组织担心会影响地下水源,政府在许多州立法禁止使用水力压裂技术开采页岩油,但是最后在 George Mitchell 的执着努力下,取得了技术性的突破,从而推动爆发了这样能源革命,这个老头子最让我钦佩的一点是关键技术突破的时候,他已经快80岁了

George Mitchell was the embodiment of the American dream. His father was a poor Greek immigrant, a goatherd who later ran a shoeshine shop in Galveston, Texas. Mr Mitchell had to work his way through university, but graduated top of his class. He left a fortune of more than $2 billion and a Texas landscape studded with examples of his philanthropy: he was particularly generous to university research departments and to Galveston.

Mr Mitchell was also the embodiment of the entrepreneurial spirit. He did not discover shale gas and oil: geological surveys had revealed them decades before he started. He did not even invent fracking: it had been in use since the 1940s. But few great entrepreneurs invent something entirely new. His greatness lay in a combination of vision and grit: he was convinced that technology could unlock the vast reserves of energy in the Barnett Shale beneath Dallas and Fort Worth, and he kept grappling with the unforgiving rock until it eventually surrendered its riches.

His stubbornness was, though, his most important quality. Investors and friends scoffed, but he spent two decades poking holes in the land around Fort Worth. “I never considered giving up,” he said, “even when everyone was saying, ‘George, you’re wasting your money’.” Then, in 1998, with Mr Mitchell approaching his 80s, his team hit on the idea of substituting water for gunky drilling fluids. This drastically cut the cost of drilling and turned the Barnett Shale into a gold mine.

从这张图来看,这场革命让美国在短短20年之内,彻底了解决了化石能源危机的问题,但是整个「页岩油革命」的完整历史,有100多年:《A Short History of Hydraulic Fracturing》

这场「页岩油革命」的意义对于美国非常的重要,正如作者所说:

If the U.S. shale revolution hadn’t happened, oil and gas prices would probably be triple what they are today, the United States might, like Europe, still be feebly climbing out of the global recession, our trade balance would be weaker, the dollar in the pits, American coal consumption and carbon emissions would be increasing, the Canadian oil sands would be the dominant source of new North American oil, poor people throughout the world would have less access to energy, the power of Putin and Middle Eastern monarchies would be dangerously magnified, and thriving Iran would be in a much better position to laugh off attempts to limit its quest for nuclear bombs.

企业的真正核心竞争力,是创新能力,带来「页岩油革命」的关键创新是支撑剂的构成和水平钻井技术,另一方面,即使没有「页岩油革命」的创新突破,也还有新能源领域的创新,特斯拉的电动汽车技术等等,这是一场全方位的围绕市场的创新竞争

前几年见到环保组织的反思,因为自身的反对而没有让核能技术更好的发展和运用,造成了现在一系列其他环境问题,我觉得这样的反思非常有意义,技术、产业、市场等等,都是非常有规律性的运作,首先要了解这一规律,然后再促进这一规律

但是另一方面,环保组织的反对,也让企业提升了环境意识,所以在运用水力压裂技术的时候,围绕而创新了深层水源的防污染技术,这是一种非常良性的反对,问题是环保组织让政府立法禁止,却增加了企业创新的难度

摘录

The shale revolution cut by 53 percent—$221 billion less—America’s annual net bill for importing oil, gas, and petroleum products. And it is having multiplier effects. With prices of its feedstock cheaper, the chemical industry has invested $138 billion “and counting” in new U.S. projects, perhaps stoking an American manufacturing revival. While the upstream and midstream oil and gas industry accounted for only 0.35 percent of the American workforce at the start of 2004, it created 6.4 percent of new jobs over the next ten years—over 400,000 in total, when good jobs were hard to find.

Miraculously, the United States achieved these benefits without directly aggravating climate change. The opposite was true: cheap natural gas displaced 200 million tons of coal consumed by Americans each year, all of it twice as polluting as gas. From 2007 to 2012, largely thanks to natural gas, U.S. annual carbon dioxide emissions fell by a world-leading 725 million metric tons, equivalent to the total emissions from Germany.

More alarming, oil, gas, and coal still account for 86 percent of the primary energy consumed in the world. We used to think we would reduce our emissions from fossil fuels because we would have no choice: demand would soon exceed our capacity to produce the fuels, especially oil, at reasonable prices. Alternative energies or radically transformed fuel efficiency would be necessary. But with oil and gas cheaper and more abundant after the shale revolution, we are now more likely to continue to consume fossil fuels. Americans are now buying fewer fuel efficient cars and trucks. And while U.S. carbon emissions are down, global emissions in 2013 were 31 percent higher than a decade before. And the world continues to get hotter by the year.

The boom is the Internet of oil, a spark from and to existing technologies that led to an industrial change of such magnitude and speed that we have woken up, after a short nap, in a once impossible world. Yet public understanding of the changes brought by the shale revolution has severely—dangerously, I believe—lagged behind understanding the Internet. This has cleared the way for hype, scaremongering, bad policy—real rips in the equilibrium that need repairing. It has prevented us from seeing the positive values in collision or candidly discussing the urgent moral, technical, and environmental challenges before us. Because of that partial understanding, we risk losing some of the benefits of America’s energy revolution. Fracking has been banned in the state where I live, by the governor I voted for. It has been outlawed in other cities, too. The Internet of oil won’t be unplugged, but it will have outages.

This book ends with an uneasy but precise equilibrium. Along the way, it presents the whole story and the essential facts. I spend my days and too many nights discussing oil and gas with my colleagues, oil company executives, and (most central to my paycheck) institutional investors who look to us to invest their capital and help them understand what the shale revolution means to them, as fiduciaries and citizens. Those conversations, the crucible of this book, have convinced me that explaining the shale revolution should rest on two near paradoxical premises. First, I believe that each of five primary perspectives on the boom—industrial, local, financial, global, and national—must inform the others. Second, I believe that each perspective must be isolated to be studied up close, to understand it in full and not to retreat from its practical and ethical challenges. Each section of this book thus takes on a different point of view: the industrial perspective of how the old iron laws of the oil and gas business were broken; the local perspective of what drilling and fracking mean to the communities where it is happening; the financial perspective of how individuals and companies made money, by disruption and luck; the global perspective, of how the shale revolution is helping and hindering the fight against climate change; and the national perspective of how the revolution could be altering America’s economy and relationships in the world.

Yet when I see a billboard like the one put up by Yoko Ono and Sean Lennon asking New York City drivers to “Imagine there’s no fracking,” I cringe. That’s because I imagine it. If the U.S. shale revolution hadn’t happened, oil and gas prices would probably be triple what they are today, the United States might, like Europe, still be feebly climbing out of the global recession, our trade balance would be weaker, the dollar in the pits, American coal consumption and carbon emissions would be increasing, the Canadian oil sands would be the dominant source of new North American oil, poor people throughout the world would have less access to energy, the power of Putin and Middle Eastern monarchies would be dangerously magnified, and thriving Iran would be in a much better position to laugh off attempts to limit its quest for nuclear bombs.

The shale revolution is a testament to American engineering, rowdiness, and cocky refusal to give up. It came so suddenly, from such small adaptations to how the oil business was usually done, and from such seemingly unnatural places—rural Pennsylvania and North Dakota rather than Silicon Valley—that it is hard to measure how fundamentally it has already reshaped our prospects.

The shale revolution also urgently poses a hard question: is there any way to retain all of its world-changing, world-improving benefits without any of its global or local costs? I wish there were a simple answer. When the planet is at stake, answers never seem to be unambiguous enough. This book’s mission is to explain the shale revolution, and its ambiguities, to allow us to make the best available decisions, ones beyond and more precise than either-or. To do so, we must start first with a total understanding, to know the green and the black, all the realities and possibilities of this once unimaginable shift. This is a book about where we have shockingly, excitingly, frighteningly found ourselves. Where we go from here, well, that’s up to us.

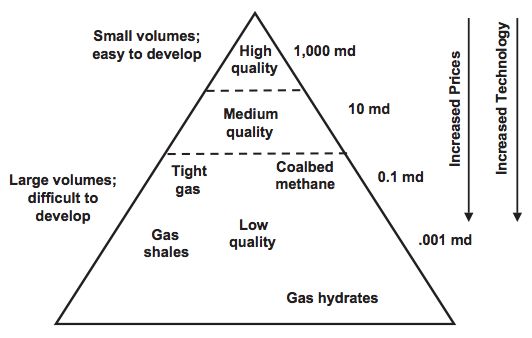

I may not have learned about the Resource Triangle on my first day in the oil business in 1995, but it couldn’t have been long after. The world, I was taught before I was taught much else, operates according to clear rules: the distribution of oil and natural gas follows a triangle shape. On the top is the good stuff: the gushers, oil almost as light as gasoline, natural gas rich with methane. The triangle gets broader with a greater volume of increasingly poorer reservoirs—less permeable, in smaller fields, the oil and gas of lower quality. Like a Life in the Middle Ages Triangle or a Contemporary Novel Triangle, the distribution is straightforward: the crappier it gets, the more of it you get.

The triangle has another feature, though: the crappier it gets, the more of it you get, the more costly to extract it gets. A century and a half of oil business experience had confirmed this.

Field declines force the industry to remain dynamic. To supply the exact same amount of oil and gas, the industry must constantly develop new fields to make up for the declining production from old ones. For companies that own drilling rigs and the like, this is the most wonderful feature in the natural order of the universe. (It’s as if you ran a construction company and your dearest fantasy came true: 4 to 5 percent of the world’s buildings disappeared every January 1, needing to be replaced.) Field declines are supportive of reasonable oil and gas prices, too: even if there is no growth in demand—and global oil demand usually grows only 1 to 2 percent per year—prices have to be stable and high enough for companies to make a profit, or hope that they can make a profit, from new wells.

At all times, the oil and gas industry needs to find new sources of hydrocarbons. In 1995, the cliché that would dominate the first dozen or so years of my career was already in use: we were at the end of the era of easy oil and gas. The easiest oil and gas, at the tip of the Resource Triangle, are the fields in which if you drill a well, the pressure of the earth spouts the oil into the sky, and 100 years later Daniel Day-Lewis wins an Oscar for being you. There are massive older fields still producing easy oil and gas today. People are still fighting over Kirkuk in Iraq, first discovered in 1927. The Ghawar field in Saudi Arabia, the biggest in history, has been in production since 1951 and still makes 5 million barrels of oil per day—about 5.3 percent of what the world needs.

But these tip-of-the-triangle fields have already been found. The last giant million-barrel-per-day-plus fields discovered were Prudhoe Bay in Alaska in 1968 and Cantarell in Mexico eight years later. While some large fields have been discovered over the last thirty years (albeit at an increasingly diminishing rate), the industry in which I learned the business was focused on developing oil and gas fields that weren’t easy: ones in inconvenient locations, collected in smaller pools, trapped in complicated geology, or containing heavier oil that requires more effort to refine (such as the Canadian oil sands).

The second thing to know about Mitchell’s advance is that the successes and failures over those seventeen years were not all binary outcomes; there was no fifty-game losing streak that ended with a stomping victory. In fields with traps sealing in the reservoir, results are often a win or a loss: you have either a producer or a duster—a dry hole. There are, however, other oil and gas reservoirs in which the outcomes are more subtle. The questions are not whether there are hydrocarbons or not, but how much, and can you produce enough of them to make money. In an ongoing source rock like the Barnett Shale, there is no doubt that there is gas underground. But as a friend likes to remind others in our business, what we do is no different than making widgets. It’s all about the margin: a well that costs $5 million to drill and recovers only $1 million worth of gas is just as bad as a duster. The S. H. Griffin #4 well was not the first well ever to produce gas from the Barnett Shale. It was the first widget to make money.

The profitability of the S. H. Griffin #4 was, to some extent, due to the increased probability of success at anything after a larger number of attempts. Yet what really allowed the S. H. Griffin #4 to come to be was that Steinsberger worked for a company led by a stubborn optimist with plenty of money and a corporate structure that permitted him to do whatever the hell he wanted to. Mitchell Energy, which was never an energy giant, spent $250 million on the Barnett Shale over seventeen years with very little to show for it. Any sane company would have shut down trying in the fifth year. And if it was engineers like Steinsberger to the rescue—and engineers smile that they are always to the rescue—with a fracking technique that finally worked, that technique was comprised of proppant, water, and a creative, entrepreneurially relentless American business culture that celebrated audacity.

I have found that horizontal drilling is one of the more difficult things for people to visualize. People can intuit how fracking works: if I aim water from a high-pressure hose at a brick wall, anarchy ensues. But it is harder to picture how to drill a well two miles deep and then turn it horizontal, especially when drilling is done with thirty-foot sections of hard steel pipe. The steel isn’t being bent by Underground Superman, nor is there some gadget that shoots a pipe horizontally from a vertical well. A well becomes horizontal after it curves over great distances. While wells vary, a typical shale well will turn from vertical to horizontal over 500 to 800 vertical feet.

Imagine a drill pipe as a pencil: it would take 300 pencils attached end to end, the height of a seventeen-story building, to get to a typical shale reservoir vertically, 9,000 feet deep. If you’re going horizontal, you first guide the pencils straight down, each new pencil driving the whole drill string deeper, for fourteen floors. Over the three lowest floors, you communicate to a motor on the bottommost pencil to angle that pencil 2 to 4 degrees closer to horizontal from the direction of the previous one. You repeat this action, with each new pencil at a gently different angle. Over forty to fifty pencils or so, in a sweet good night, the pencil string goes from being upright to lying on its side. Reality is messier than pencils, of course. In an oil or gas well, the move from vertical to horizontal is not always a calm slumber. There is considerable “tortuosity” and variance in each angle of repose as the well responds to rock.

单词列表:

| words | sentence |

|---|---|

| Maine | I had never been to Northeast Harbor, Maine, before |

| obscenely | The July weather was obscenely perfect |

| gusher | leaps in productivity were aggregating into a gusher of American oil and gas production |

| canapés | was not that amid the canapés we were discussing seventy-year-old |

| emissions | Isn’t it decreasing carbon emissions? |

| extrapolates | each blind man touches only part of an elephant and extrapolates from the part he feels |

| pervasive | But too much has changed, the effects are too pervasive |

| abundant | we now live in a country of abundant—maybe too abundant—oil and gas |

| contemplating | And policymakers outside the United States are contemplating their own national direction |

| thorny | are trying to answer the thorny questions |

| wildcatter | I couldn’t tell you what a wildcatter was or what Texas was like |

| Goldman Sachs | In my first job out of college, at Goldman Sachs |

| pasta sauce | stretched a jar of pasta sauce over as many noodles as it could go |

| LeBron | We knew that America could conquer the world with iPhones and LeBron and #hashtag |

| apocalypse | Mad Max apocalypse as we battled each other |

| tenfold | From 2007 to 2014, U.S. shale gas production increased tenfold |

| breakneck | an almost 60 percent decline in oil prices in four breakneck months |

| left-for-dead | this U.S. shale renaissance has happened in left-for-dead places like West Texas |

| per capita | North Dakota now has double the oil production per capita of Kuwait |

| Methane | Methane might or might not be an issue |

| yappy | when they try to promote a too easy equilibrium, I get frustrated and yappy |

| billboard | when I see a billboard like the one put up by Yoko Ono |

| boredom | But the consumers’ unimpressed boredom may be the boom’s most conspicuous achievement |

| conspicuous | But the consumers’ unimpressed boredom may be the boom’s most conspicuous achievement |

| backwaters | I suspect I was assigned to the backwaters because I came to the firm armed with all the stock market savvy a History degree could provide |

| imperialism | had been spent researching British working-class attitudes toward imperialism |

| circa | circa 1902, a topic that didn’t even excite the British |

| Gulf War | except for the brief oil price spike around the first Gulf War |

| drilling rigs | For companies that own drilling rigs and the like |

| seismic | for which the first seismic surveys were conducted in 1993 |

| quarterback | The oil industry then was like a star quarterback at the end of his career |

| Fort Worth | a natural gas play outside Fort Worth |