印度在线零售大竞赛

接下来的15年,印度将比其他任何国家迎来更多的在线购物人群。

电子商务行业为了他们的客户已经展开疯狂的争夺。

2016年3月5日

孟买郊区,早晨,宁静、天气温和。

斑驳的阳光洒在尘土飞扬的街道,一只流浪狗在垃圾堆中翻找食物,一些小商铺的百叶窗已经打开。

一名男子推着一台装满橘子的车,堆得像金字塔的形状。

一名投递男孩,名叫阿尼尔,正在飞驰在他的路线上,摩托车是从他叔叔那借来的,他的投递背包和他一样大。

这男孩已经工作好几个小时了,规划路线,小心翼翼的将货物塞满他的背包,得确保到目的地之后可以在包的顶部拿出来。

阿尼尔走进一栋公寓楼,挤压背包以挤进狭窄的电梯,将一件衬衫送给一个21岁的出租车司机。

在临近的塔楼立他将一个智能手机的订单交给一位16岁的人,他使用几个应用程序为他的家庭成员购物。

不远处,一位78岁的老奶奶是特别高兴的客户——在她孙子的帮助下,她买了一些别的地方找不到的陶土罐,还有一些廉价的高品质莎丽(南亚妇女服饰)。对阿尼尔来说,这是一项艰苦的工作。但是他确信印度的电子商务已无处不在、处于上升期,他希望能跟着趋势一起飞。

接下来的15年,印度将比其他任何国家迎来更多的在线购物人群。

去年电商零售已经达到160亿美元;2020年,根据摩根士丹利的报告,在线零售市场可能增长7倍以上。

印度的这个销售预期增长比其它任何市场都要快。

这吸引了大量的电子商务公司,其影响可能远远不止是替代线下零售投资而已。

印度的小企业很少有机会获得贷款;其消费者的大部分没有信用卡,也不需要信贷。电子商务公司是投资物流、帮助商户借贷和为消费者提供新的支付工具。AmitAgarwal,负责运营 印度亚马逊,寄希望于"我们实际上可能变成一种改变印度的催化剂:印度的购买方式、印度的销售方式,甚至改变生活方式。"

王冠上的宝石

亚马逊希望将印度打造为仅次于美国的第二大市场。

尽管此时,仅有12%的市场占有率,它远落后于本地成长起来的企业,Flipkart (45%) ,Snapdeal (26%)。

以上三家企业,以及一些较小的竞争对手,支出速度惊人。

随着全球市场萎靡和硅谷独角兽的绊倒,国际资金枯竭的情况使之成为可能。

怀疑公司目前计划的可持续性被强调,在2 月26 日,一家摩根士丹利(morganstanley) 的共同基金,特别为此风险——将其在flipkart 公司股权的价值,减记27%。

对大量投递员来说,改变印度的语气可能是一种欺骗,而它不是因为好逸恶劳。

印度的远见者通过回忆中国的案例保持斗志。

从2010年到2014年,中国的电子商务增长了近600%,使这个国家今天成为世界上最大的电子商务市场。

这在很大程度上得益于土著公司的成长:强大的亚马逊只能咬在本土巨头阿里巴巴和JD.com;eBay 都已经离开了舞台。

而在这个过程中,中国顶尖的电子商务公司提供服务的范围大得惊人。

阿里巴巴,成立由马云于1999 年,如今市值美元1840亿,提供了最好的例证。

为了平息公众对网上购物的忧虑,阿里巴巴创建了支付宝,代管持有购物者的付款,直到他收到他的订单。

该工具已经演变成金融服务公司,蚂蚁金融,去年服务超过400 万支付宝账户,超过2 亿美元贷款给小企业和企业家。

为中国消费者提供外国商品进入该公司的服务包括但不限于:市场营销、运输和海关的帮助。

阿里巴巴现在为偏远的地区建设服务中心,在那里购物者可以预定,收货和出售货物,以及支付他们的账单。

这是一个长远步骤,表明它的企图不仅在于从中国人的消费增长中受益,还要塑造和加速这一进程。

从已经成功的案例中可以看出,电子商务企业越早介入一个国家的发展,它能发挥的作用可能就越宽。

对电子商务来说,印度在许多方面是比中国更严格市场。

它的人口更贫穷,它的基础设施更糟。但其前景看起来也引人注目。

人均收入,2014 年是$1,570,到2025年可能达到两倍。

三分之二的印度人不到35岁,其中通过手机访问互联网的人数非常庞大。

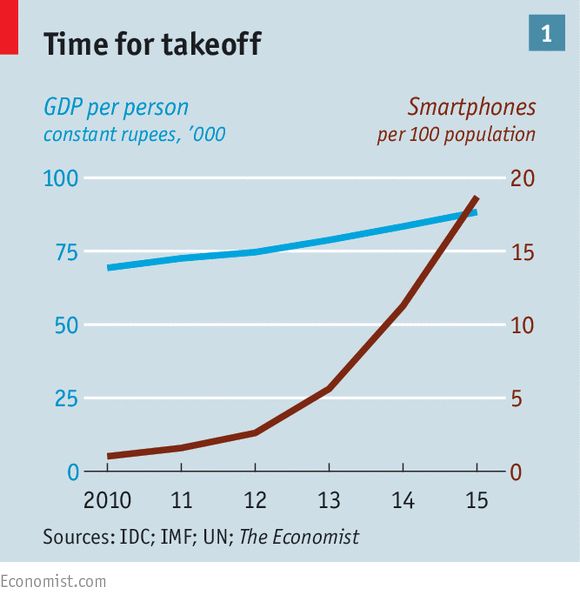

在2014 年12 月智能手机已经占印度手机的五分之一,根据高盛的数据。仅仅是六个月后,就达到了四分之一(见图表1)。

摩根士丹利预计互联网渗透率从2015年的32%上升到2020年的59%。到了2030年,印度预计将成为一亿人规模的数码市场。

增长到接近中国规模,第二大市场前景吸引了那些获得首轮融资的企业。

鲍勃 ·范戴克,Naspers首席执行官,一家南非公司,支持JD.com和腾讯(中国最大的社交媒体公司),说他寻找人口众多、智能手机的使用刚兴起,并且缺乏零售连锁店的地区投资。印度,在商场、超市和品牌的连锁店,或分析师所称的"有组织的零售",只是10%左右完全符合条件。

中间商

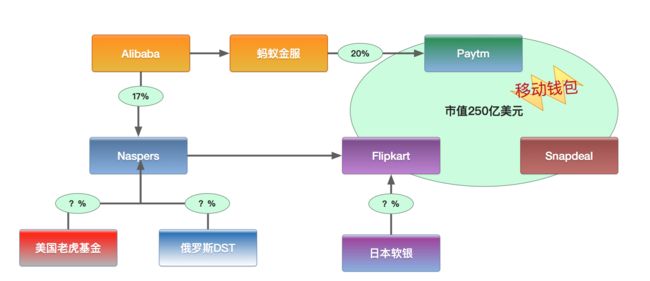

Naspers在Flipkart 公司拥有17%的股份;其他JD.com投资者亦支持本公司,包括纽约的老虎基金,一个俄罗斯的基金-DST全球。

日本的软银,阿里巴巴的大投资者,自2013 年开始支持Snapdeal,阿里巴巴本身也在去年8 月跟投。

同时阿里巴巴的蚂蚁金融在印度的Paytm,拥有20%的股份,并开始作为一个移动钱包公司与Snapdeal和flipkart 公司同在一个在线的市场竞争。

这三家公司市值加起来的几乎达到250亿美元。

与那些试图复制其在中国成功的投资者,亚马逊正在寻求弥补了它的失败。

为了减少去年到阿里巴巴的天猫网站上开店的耻辱,杰夫贝佐斯确定,这一次,积累了更多经验,而且是在更加开放的市场,局面将会不同。

Flipkart 公司成立于2007 年,当时亚马逊是它的榜样。

该公司开始为一家书店;两个工程师开启了它,萨尔萨钦和萨尔宾尼(不相关),曾经在亚马逊工作。

贝佐斯先生,虽然,他的意见是如果任何人如果想成为印度亚马逊,它应该是亚马逊。

在2014 年,flipkart 公司宣布获得10亿美元的投资后不久,贝佐斯先生穿上在班加罗尔的印度服饰,搭乘彩虹色卡车,交给Agarwal先生一张$20亿的支票。

这家公司2015年营业收入超过1000亿美元,因此股东们大约有更多的利润可以如此慷慨援助。

无论Flipkart 公司、亚马逊,或任何其他大的竞争对手都是跟随亚马逊在西方成功的零售战略。

印度法律规定外资电子商务公司不得拥有库存,这种情况下作为一个简单的零售商就不可能了。

因此印度顶尖的电子商务公司看起来更像阿里巴巴模式。

Flipkart 公司已经成为一个集市:卖家提供一切东西,从移动电话到洗衣机到手袋。Snapdeal、亚马逊和Paytm也是。

公司狂热地打价格战,打折正在吞噬他们自己的利润。长远来看,他们必须通过精细化服务,提高自己在卖家和消费者中的识别度,并向更多的印度人提供更好、更广泛的产品。

实现这一目标的第一步是增加平台公司上的卖家— —卖家,毕竟,他们将支付佣金和航运费用。

所以公司提供一系列的服务来吸引企业到他们的网站。

Flipkart 公司的方案包括:教卖家如何管理销售高峰,通过排灯节(印度节日)掌握时尚品牌的趋势和生产。

在2 月亚马逊发布了一个在轮子上的旅行工作室,提供培训、摄影和其他服务,以帮助商户走到线上。

但他们提供的最重要帮助是放宽信贷。

小企业,仅能给的少量的财务报表和有限的信用历史,长久以来从印度的银行获得贷款的非常困难。

他们常常依靠从邻居或家人获得昂贵的贷款。

电子商务公司有强烈的动机,使他们更好地提供信贷 — —因为他们有权访问在线销售数据,他们处于有利的地位,可用以帮助贷款人判断信用风险。

以SumitAgarwal为例(和亚马逊的加瓦没有关系),一个年轻的企业家,在2011 年开始在线制鞋企业。

在他新德里的仓库里,工人在鞋盒堆积的高塔中间打包、扫描。

早期的不确定性;他的家人开始时反对开公司,他说,是”见鬼!这家伙在做什么?” 如今在首都,这种企业家寻求资本借以生长,要容易多了。

当Agarwal先生登录到他在亚马逊印度上的卖方帐户,他的屏幕上列出了能提供的短期贷款,其费率根据他的交易数据计算得出。

其他电子商务公司有类似的计划。在一月Snapdeal宣布印度国家银行会立即批准高达37,000 美元贷款,如果它认可Snapdeal对借款人提供的数据。

一旦一个网站拥有卖家,第二个挑战是帮助消费者购买他们的商品。

阿尼尔需要在他的路线上携带一个笨重的信用卡读卡器,但大多数人付现金。

电子商务网站想要改变这一现状。Paytm允许客户将钱添加到数字钱包,然后被用于在线购物、手机充值、借钱给一个朋友,支付一份帐单或使用类似超级出租车的服务。它有1.2亿数字钱包账户,近六倍于印度的信用卡数量。

Snapdeal4月份买了它自己的移动支付公司。今年 2 月,亚马逊购买在线支付服务。

微妙的平衡

如果消费者购买产品,接下来的任务就是投递它。交付本身不是什么新鲜事。

印度人很久以前就有当地的送货员 Kirana 收到一罐黄油— —主宰印度零售的街头小店。

但能够提供更大的规模是一项挑战。该国的邮件服务,印度邮政,装备不良,等待顾客试穿衣服和思考返回它。

因此新进场者都在建设网络。但印度的交通混乱如地狱,地址也含糊不清。

一个名为Delhivery的公司已经启动,聘请超过15,000的工作人员,从研究员到高管都是从Facebook和顶级顾问公司挖来的。

其总部设在古尔冈,可以让一批工程师集中在一起,远离外界干扰,疯狂地敲键盘。

Delhivery,配合大量的电子商务公司,利用机器学习来细分印度的邮政编码,以更好地在地图上标记特殊的目的地。

SandeepBarasia,该公司的总经理说:"我们可以知道寺庙旁边的黄门的房子"。

本公司可以一夜之间将货物移到700(?)或小型配送中心,以避免在营业时间内通过拥挤主干道。

然后数以千计的投递男孩,全天从配送中心分发,在他们的自行车上承载超过20公斤。

电子商务公司也正在制定他们自己的解决方案。

一些投资,比如仓库,非常简单。其他人则不是这样。Flipkart 公司去年开始用孟买的著名网络dabbawallas,或午餐送货人,当他们拿起客户的午餐铁盒的时候送货。

亚马逊有一个试点项目,客户在线订购食品,让距离他们最近的 kirana送货。

总的来说,电子商务公司称,这些实验可以创建新的真正的全国市场。

Neelkanth米什拉的一家银行,瑞信指出那些道路施工,电气化和手机大大增加了农村的工资水平,以及对商品的需求(见图表2)。

Flipkart 公司说,其约一半的销售额来自印度境外的大城市。Snapdeal声称超过60%。它最近推出了七个区域语言版本的网站。

他们建立了市场公司向小企业提供援助。

"亚马逊网站上的一些大卖家在班加罗尔一个角落里只有一家商店;他们乐于卖到每个商店周围的五公里,”亚马逊的Agarwal先生说到。

"现在他们航运订单到克什米尔和印度东部。"亚马逊正在帮助超过印度中小企业出口。

Snapdeal 的若斯特沙利文巴尔同样乐观:”我们追求的是帮助印度的小企业规模扩大的同时,实现社会、经济和地理的卓越平衡。”

这些大胆的计划事实上还有两个顽固的阴影。

第一,消费折扣,营销活动和新的招聘意味着公司并无任何赚钱。

访问任何公司的大厅,你会看到成群的求职者。像阿尼尔一样的投递男孩子是抢手货— —在其分支机构的最高执行者,他挣的钱约14,000卢比(约合200 美元)每个月。

可以预见的是,亚马逊远超其竞争对手。

去年的销售额是其损失的三分之二大小。阿加瓦尔先生并不介意缺乏利润。"增长优先,"他解释道。

AnkitNagori,Flipkart 公司的首席商务官说,他的公司的最重要指标不是利润率而是新客户数、他们多久购物,他们买多少和交货速度。"如果你为解决这四件事,"他争辩说,”然后总收入和账面利润将会步入正轨"。

更多的投递员

第二个问题是监管。

拥有库存的代价是禁止外资公司。企业在他们的网站仅能实现有限的产品质量控制,摩根士丹利(morganstanley)帕拉古普塔指出,他们不能精简该国的分散的供应链。Flipkart 公司已成为相互关联的实体,包括一家控股公司在新加坡,在追求利润最大化同时要遵守印度的规则。

尽管如此,印度政府可能受到贸易保护主义压力。

传统零售商称在线市场无视对外国直接投资规则。Facebook最近废置了计划为印度人提供免费的互联网服务,包括其自身,引起了关于"数字殖民主义”风险的轩然大波。

线下零售商正在聚精会神地看着这一切。

Kiranas是相对地保护,感谢较低的税收法案和有限的持有的成本(他们存储很少)。大商店和商场是另一个故事(见图表3)。

“令我关注的是在很短的时间,电子商务已占据一半的有组织的市场,"波士顿咨询集团的Abheek说。

"两年跌落这条线,三年跌落这条线,电子商务市场将更庞大。”

大型外国零售商— — 如宜家,瑞典家具公司,年后的混乱最后可能开放印度的商店 — — 不能直接在线销售。

事项简单为印度零售商,但他们的路线依然是多云。信实工业企业集团,超过1 万平方米的车间,规划了自己的电子商务创业。未来组,开创了我国大型超市,舾装小店主和企业家与数字目录,以便消费者可以订购未来集团产品在那里永远不会有的地方一家商店。然而该公司已经缩放回一些电子商务及其更雄心勃勃的计划。"你做的越多销售,你会失去更多的钱,"缪斯对此感兴趣,未来集团创始人。"你需要有持续的资金资助和人家背你"。

其时,大公司的部门有那些需求得到满足。"你必须有足够深的口袋,至少三个,可能四个大玩家"说先生进行。"它会打很高的成本"。阿里巴巴和亚马逊这样的公司看看那作为值得付出部分,因为,正如他们应用他们在中国和印度学到的了,所以它们将使用其印度的经验在他们进入下一个市场的成本。阿里巴巴,不满足于回Paytm和Snapdeal,也直接在印度企业试图拉拢。在12 月,它说它将有助于印度公司融资与物流,所以他们可能会使用阿里巴巴的平台,出口到中国和超越。最终,马英九喜欢说,任何一个消费者应该能够从任何卖方,在世界任何地方购买。那些购买的越多,经历了一个他的公司,越好。

Matters 是原始的印度零售商,但是它们的路线并不明朗。

Reliance工业企业集团, 拥有超过1 万平方米的车间,规划了自己的电子商务创业。

未来集团,开创了这个国家的大型超市,为小店主和企业家提供数字目录,以便消费者无论在那里,都可以订购未来集团产品。然而该公司已经压缩了一些电子商务及其更雄心勃勃的计划。"你做的越多销售,你会失去更多的钱,"缪斯对此感兴趣,未来集团创始人。"你需要有持续的资金资助和众人支持"。

与此同时,这个行业的大公司也将面临一些问题。

"你必须有足够深的口袋,至少三个,可能是四个大玩家” 辛格先生说。

"它会产生很高的成本"。阿里巴巴和亚马逊这样的公司会评估那些成本是否值得付出,因为,正如他们应用他们在中国和印度学到的,它们将使用其印度的经验当他们进入下一个市场的时候。阿里巴巴,不满足于仅仅持有Paytm和Snapdeal,也在试图直接拉拢印度企业。

在12 月,它说它将有助于印度公司融资与物流,如果它们使用阿里巴巴的平台,出口到中国或更多地方。

最终,马云喜欢说,任何一个消费者应该能够从任何卖方,在世界任何地方购买。通过他的公司购买的越多,越多好处。

与此同时,面对这些无处不在的巨头,本土企业家希望他们本地的触觉会给他们划定边缘,并寻找海外投资者支持他们。

其中许多人将会失败:印度在它之前还不能提供给一个例子,如何赚取利润,而且它可能需要很长的时间。

但只要其中一些努力生存下去,他们将为速度进步和创新,在市场中发展壮大。

正如亚马逊的先生阿格沃尔说,"如果数以百万计的小、中型企业在那里,制造商和零售商,能将他们的产品卖到世界任何地方— — 这就是转型。"

Online retailing in India

The great race

In the next 15 years, India will see more people come online than any other country. E-commerce firms are in a frenzied battle for their custom

Mar 5th 2016

IT IS a quiet morning on the outskirts of Mumbai, the air still mild. Dusty streets are dappled with sunlight, a stray dog rummages through some rubbish, the shutters are lifted on a few tiny shops. A man pushes a cart bearing a pyramid of oranges. And a delivery boy named Anil is already racing along his route on a motor bike borrowed from his uncle, his delivery backpack as large as he is. He has been up for hours, planning his route and carefully filling his bag with the packages to be dropped off first stacked near the top.

Anil enters a block of flats, squeezes his backpack into a narrow lift and delivers a shirt to a 21-year-old taxi driver. In a neighbouring tower he hands a smartphone case to a 16-year-old who uses several apps to do the shopping for his family. A short ride away, a 78-year-old grandmother is a particularly pleased customer—with help from her grandson, she has bought some clay pickling jars that she couldn’t find elsewhere and some high-quality saris at a knock-down price. For Anil, it is gruelling work. But he is betting that e-commerce in India has nowhere to go but up, and he wants to ride up with it. In the next 15 years India will see more people come online than any other country. Last year e-commerce sales were about $16 billion; by 2020, according to Morgan Stanley, a bank, the online retail market could be more than seven times larger. Such sales are expected to grow faster in India than in any other market. This has attracted a flood of investment in e-commerce firms, the impact of which may go far beyond just displacing offline retail.

India’s small businesses have limited access to loans; most of its consumers do not have credit cards, or for that matter credit. The e-commerce companies are investing in logistics, helping merchants borrow and giving consumers new tools to pay for goods. Amit Agarwal, who runsAmazon.in, holds out the hope that “We could actually be a catalyst to transform India: how India buys, how India sells, and even transform lives.”

The jewel in the crown

Amazon wants to make India its second-biggest market, after America. For the time being, though, with just 12% of the market, it lags behind the home-grown successes, Flipkart (45%) and Snapdeal (26%). All three, as well as some smaller competitors, are spending at a blistering rate. As global markets dip and Silicon Valley unicorns stumble, the international funding that makes this possible may dry up. Doubts about the sustainability of the companies’ present plans were underlined when, on February 26th, one of Morgan Stanley’s mutual funds marked down the value of its stake in Flipkart by 27%. If the prospect of changing India a billion deliveries at a time is a beguiling one, it is not for the faint-hearted.

India’s visionaries keep their spirits up by remembering the example of China. Chinese e-commerce grew by nearly 600% between 2010 and 2014, making the country the biggest e-commerce market in the world today. It managed this largely through the growth of indigenous companies: mighty Amazon merely nips at the heels of home-grown giants Alibaba andJD.com; eBay has all but left the stage. And in the process China’s top e-commerce firms came to offer an astonishing range of services.

Alibaba, founded by Jack Ma in 1999 and now valued at $184 billion, provides the best illustration. To calm anxieties about buying online Alibaba created Alipay, which holds a shopper’s payment in escrow until he receives his order. The tool has evolved into a financial-services company, Ant Financial, which last year serviced more than 400m Alipay accounts and made over 2m loans to small businesses and entrepreneurs. To provide Chinese consumers with access to foreign goods the firm’s services include not just online listings but marketing, shipping and help with customs.

Alibaba is now building service centres in remote areas where shoppers can order, pick up and sell goods, as well as pay their bills. It is a further step in its attempts not merely to benefit from the growth in Chinese consumption, but to shape and accelerate it. The degree to which it has succeeded suggests that the earlier an e-commerce company arrives in a country’s development, the wider its role might be.

India is in many ways a tougher market for e-commerce than China. Its population is poorer and its infrastructure worse. But its prospects look remarkable. Income per person, which in 2014 was $1,570, could be twice that by 2025. Two-thirds of Indians are younger than 35, and their phones give a huge number of them access to the internet. In December 2014 smartphones accounted for one in five Indian mobiles, according to Goldman Sachs. Just six months later, they accounted for one in four (see chart 1). Morgan Stanley expects internet penetration to rise from 32% in 2015 to 59% in 2020. By 2030, India is projected to be a one-billion-person digital market.

The prospect of a second market growing to a near-Chinese size attracts those who made a packet the first time round. Bob van Dijk, the chief executive of Naspers, a South African firm that backed JD.com and Tencent, China’s largest social-media company, says he looks for countries with big populations, rising smartphone use and few retail chains. India, where malls, supermarkets and branded chains, or what analysts call “organised retail”, account for just 10% or so of the total market, fits the bill perfectly.

The middlemen

Naspers owns a 17% stake in Flipkart; other JD.com investors, including Tiger Global Management, in New York, and DST Global, a Russian fund, have also backed the company. Japan’s SoftBank, a big investor in Alibaba, has backed Snapdeal since 2013, and Alibaba itself followed suit last August. Meanwhile Alibaba’s Ant Financial owns a 20% stake in India’s Paytm, which began as a mobile-wallet company and now competes with Snapdeal and Flipkart as an online marketplace. The three firms have a combined valuation of almost $25 billion.

In contrast to those investors trying to recapitulate their Chinese success, Amazon is seeking to make up for its failure. Reduced last year to the ignominy of having to open a shop on Alibaba’s Tmall site, Jeff Bezos is determined that this time, with more experience and in a more open market, things will be different.

When Flipkart was founded, in 2007, Amazon was obviously its model. The company began as a bookseller; the two engineers who started it, Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal (not related), had worked for Amazon. Mr Bezos, though, is of the opinion that if anyone if going to be the Amazon of India, it should be Amazon. In 2014, shortly after Flipkart announced a $1 billion round of funding, Mr Bezos donned Indian clothes in Bangalore, hopped aboard a rainbow-coloured truck and handed Mr Agarwal a $2 billion cheque. A firm which earned over $100 billion in 2015 and has shareholders content to see more or less nothing by way of profits can afford such largesse.

Neither Flipkart, Amazon, nor any of the other big competitors are following the retail strategy that led to Amazon’s success in the West. Indian regulations bar foreign-backed e-commerce firms from owning inventory, and so acting as a straightforward retailer is not an option. As a result India’s top e-commerce companies look much more like Alibaba. Flipkart has become a marketplace where sellers offer everything from mobile phones to washing machines to handbags. Snapdeal, Amazon and Paytm run marketplaces too. The firms compete feverishly on price, offering discounts that chomp away their own margins. In the long term, they must differentiate themselves by honing services for sellers and shoppers alike, and offering a better, broader range of products to more Indians than would have them otherwise.

The first step to that goal is to boost the number of sellers on the company’s platform—it is the sellers, after all, who pay commissions and shipping fees. So companies offer a range of services to lure businesses to their sites. Flipkart’s programmes range from teaching sellers how to manage peak sales duringdiwalito advising fashion brands on trends and production. In February Amazon announced a travelling studio-on-wheels, offering training, photography and other services to help shop-owners come online.

But the most important help they offer is in easing access to credit. Small businesses, given their scarce financial statements and limited credit history, have long had trouble obtaining loans from India’s banks. They often rely on expensive loans from neighbours or family. The e-commerce companies have strong incentives to make them better offers—and because they have access to online-sales data they are in a privileged position from which to help lenders judge credit risk.

Take Sumit Agarwal (no relation to Amazon’s Mr Agarwal), a young entrepreneur who started an online shoe business in 2011. In his warehouse in New Delhi workers pack and scan shipments among towers of shoeboxes. The early days were uncertain; his family’s reaction when the firm started, he says, was “What the hell is this guy doing?” Now it is easier for such entrepreneurs to find the capital with which to grow. When Mr Agarwal logs into his seller’s account onAmazon.inhis screen offers a column of short-term loans, their rates calculated using data from his transactions. Other e-commerce firms have similar schemes. In January Snapdeal announced that the State Bank of India would approve loans of up to $37,000 instantly if it liked the look of the data that Snapdeal provided on the borrower.

Once a site has sellers, the second challenge is to help consumers buy their wares. Anil carries a clunky credit-card reader with him on his rounds, but most people pay cash. The e-commerce sites want to change that. Paytm lets customers add money to a digital wallet that can then be used to shop online, top up a mobile phone, lend money to a friend, pay a bill or use a service such as an Uber taxi. It has 120m digital-wallet accounts, nearly six times India’s number of credit cards. Snapdeal bought its own mobile payments company in April. Amazon purchased an online-payments service in February.

A fine balance

If a consumer does buy a product, the next task is delivering it. Delivery itself is nothing new. Indians have long been able to have a delivery boy from the localkirana—the cornershops that dominate Indian retail—bring them a stick of butter. But being able to deliver on a larger scale is a challenge. The country’s mail service, India Post, is ill-equipped to wait while a shopper tries on akurtaand ponders returning it. So newcomers are building networks. But India’s traffic is hellish and its addresses vague.

A startup named Delhivery has hired more than 15,000 staff, from developers to executives poached from Facebook and posh consultancies. Its headquarters in Gurgaon are so packed that engineers spill onto an outdoor porch, tapping their keyboards furiously. Delhivery, which works with a number of e-commerce firms, is using machine learning to subdivide India’s postcodes, the better to map idiosyncratic descriptions. “We’ll know the house with the yellow door next to the temple,” says Sandeep Barasia, the managing director. The company moves goods to 700 or so small distribution centres overnight to avoid congested main roads during business hours. Thousands of delivery boys then dash to and from the distribution centres throughout the day, bearing more than 20 kilos on their bikes.

E-commerce companies are devising their own solutions, too. Some investments, such as warehouses, are straightforward. Others are less so. Flipkart last year began using Mumbai’s famous network ofdabbawallas, or lunch-delivery men, to drop off packages when they picked up customers’ lunch tins. Amazon has a pilot programme that lets customers order groceries online and have them delivered from the nearestkirana.

Together, e-commerce firms say, these experiments could create a new truly national marketplace. Neelkanth Mishra of Credit Suisse, a bank, points out that road construction, electrification and mobile phones have stoked big increases in rural wages, and thus demand for goods (see chart 2). Flipkart says that about half its sales come from outside India’s big cities. Snapdeal claims more than 60%. It recently launched seven regional-language versions of its website.

As they build out their markets the firms trumpet their assistance to small businesses. “Some of the big sellers on Amazon only had a shop in a corner of Bangalore; they were happy selling to five kilometres around each shop,” declares Amazon’s Mr Agarwal. “Now they are shipping orders to Kashmir and eastern India.” Amazon is helping more than 6,000 Indian businesses export, as well. Snapdeal’s Kunal Bahl is equally expansive: “Our ambition is to be a great social, economic and geographic equaliser for the small businesses of India as they scale up.”

All these bold plans are clouded by two obstinate facts. First, spending on discounts, marketing campaigns and new hires means none of the companies has yet made money. Visit any firm’s lobby and you will meet herds of job applicants. Delivery boys like Anil are in hot demand—a top performer in his branch, he earns about 14,000 rupees ($200) each month.

Amazon is, predictably, outspending its competitors. Last year its sales were two-thirds the size of its losses. Mr Agarwal is not bothered by a lack of profit. “The priority is growth,” he explains. Ankit Nagori, Flipkart’s chief business officer, says that the most important metrics for his company are not margins but the number of new customers, how often they shop, how much they buy and the speed of delivery. “If you solve for these four things,” he contends, “then the top line and bottom line will fall in place.”

A billion deliveries more

The second problem is regulatory. Forbidding foreign-backed firms from owning inventory has costs. Companies have limited control over the quality of products on their sites, points out Morgan Stanley’s Parag Gupta, and they can do little to streamline the country’s fragmented supply chain. Flipkart has become a tangle of interlinked entities, including a holding company in Singapore, in an attempt to obey India’s rules while maximising profits.

India’s government may nonetheless come under protectionist pressure. Traditional retailers allege that the online marketplaces flout rules against foreign direct investment. Facebook’s recently scuttled plan to offer Indians free internet services, including its own, sparked a furore over the risks of “digital colonialism”.

Offline retailers are watching all this intently.Kiranasare relatively protected, thanks to meagre tax bills and limited carrying costs (they store little). Big shops and malls are another story (see chart 3). “What is remarkable for me is that in a very short time, e-commerce has become half of what the organised market is,” says Abheek Singhi of the Boston Consulting Group. “Two years down the line, three years down the line, the e-commerce market could be larger.”

Big foreign retailers—such as Ikea, a Swedish furniture company, which after years of kerfuffle may finally be opening an Indian store—cannot sell directly online. Matters are simpler for Indian retailers, but their course remains cloudy. Reliance Industries, a conglomerate with over 1m square metres of shop floor, is planning its own e-commerce venture. Future Group, which pioneered hypermarkets in the country, is outfitting small shop-owners and entrepreneurs with digital catalogues so that consumers can order Future Group products in places where there will never be a store. However the firm has scaled back some of its more ambitious plans for e-commerce. “The more sales you do, the more money you lose,” muses Kishore Biyani, Future Group’s founder. “You need to have continuous funding and someone to back you.”

For the time being, the big companies in the sector are having those needs met. “You have at least three, potentially four large players with deep enough pockets,” says Mr Singhi. “It’s going to play out at a very high cost.” Companies like Alibaba and Amazon see that cost as worth paying in part because, just as they applied what they learned in China to India, so they will use their Indian experience in the next markets they move into. Alibaba, not content to back Paytm and Snapdeal, is also courting Indian businesses directly. In December it said it would help Indian firms with financing and logistics so they might use Alibaba’s platforms to export to China and beyond. Eventually, Mr Ma likes to say, any consumer should be able to buy from any seller, anywhere in the world. The more of those purchases go through one of his firms, the better.

And everywhere these giants go, home-grown entrepreneurs will be hoping that their local acumen will give them an edge and looking for overseas investors to back them. Many of them will fail: India does not yet offer an example of how to make a profit, and it may be a long time before it does. But as long as some of these efforts survive, they will serve to speed progress, and innovation, in developing markets. As Amazon’s Mr Agarwal says, “If millions of small, medium enterprises out there, manufacturers and retailers, can...sell their product anywhere in the world—that’s transformational.”

译者注

top line : 财务上指总收入

bottom line :财务上指利润

the organized market :未确定