1 the brain and behavior

abstract

two opposing views have been advanced on the relationship between brain and behavior

the brain has distinct functional regions

the first strong evidence for localization of cognitive abilities came from studies of language disorders

affective states are also mediated by local, specialized systems in the brain

mental processes are the end product of the interactions between elementary processing units in the brain

content

5

the last frontier of the biological sciences–the ultimate challenge–is to understand the biological basis of consciousness and the brain processes by which we feel, act, learn, and remember

two opposing views have been advanced on the relationship between brain and behavior

6

Golgi developed a method of staining neurons with silver salts that revealed their entire cell structure under the microscope. he could see clearly that each neuron typically has a cell body and two types of processes: branching dendrites at one end and a long, cable-like axon at the other. using Golgi’s technique, Ramon y Cajal discovered that nervous tissue is not a syncytium, a continuous web of elements, but a network of discrete cells. in the course of this work Ramon y Cajal developed some of the key concepts and much of the early evidence for the neuron doctrine–the principle that individual neurons are the elementary building blocks and signaling elements of the nervous system

6

pharmacology made its first impact on our understanding of the nervous system and behavior at the end of the 19th century when Claude Bernard in France, Paul Ehrlich in Germany, and John Langley in England demonstrated that drugs do not act just anywhere on a cell , but rather bind discrete receptors typically located in the surface membrane of the cell. this insight led to the discovery that nerve cells can communicate with each other by chemical means

6

psychological thinking about behavior dates back to the beginning of Western science when the ancient Greek philosophers speculated about the causes of behavior and the relation of the mind to the brain. in the 17th century Rene Descartes distinguished body and mind. in Descartes’ dualistic view the brain mediates perception , motor acts, memory, appetites, and passion–everything that can be found in the lower animals. but the mind–the higher mental functions, the conscious experience characteristic of human behavior– is not represented int the brain or any other part of the body but in the soul, a spiritual entity that communicates with the machinery of the brain by means of the pineal gland, a tiny structure in the midline of the brain. later in the 17th century Baruch Spinoza began to develope a unified view of mind and body

in the 18th century Western ideas about the mind split along new lines. empiricists believed that the brain is initially a blank slate( tabula rasa) that is later filled by sensory experience, whereas idealists, notably Immanuel Kant, believed that our perception of the world is determined by inherent features of our mind or brain. in the mid-19th century Charles Darwin set the stage for the modern understanding of the brain as the seat of all behavior. thus the study of evolution gave rise to ethology, the investigation of the behavior of animals in their natural setting, and later to experimental psychology, the study of human and animal behavior under controlled conditions. at the beginning of the 20th century Sigmund Freud introduced psychoanalysis. as the first systematic cognitive psychology, psychoanalysis framed the enormous problems that confront us in understanding the human mind

7

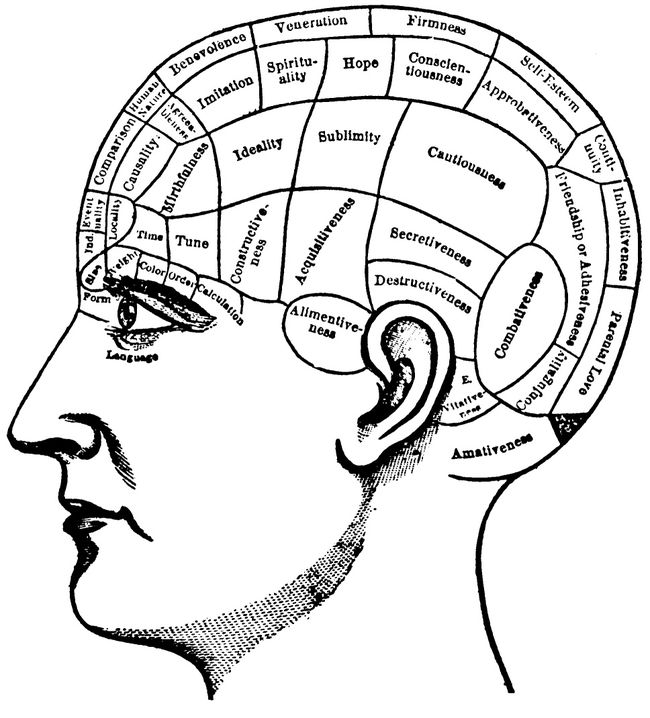

attempts to join biology and psychological concepts in the study of behavior began as early as 1800, when Franz Joseph Gall, a Viennese physician and neuroanatomist, proposed two radically new ideas. first, he advocated that the brain is the organ of the mind and that all mental functions emanate from the brain. in so doing, he rejected the idea that mind and body are separate entities. second, he argued that the cerebral cortex did not function as a single organ but contained within it many organs, and that particular regions of the cerebral cortex control specific functions. Gall enumerated at least 27 distinct regions or organs of the cerebral cortex; later many more were added, each corresponding to a specific mental faculty. Gall assigned intellectual processes, such as the ability to evaluate causality, to calculate, and to sense order, to the front of the brain. instinctive characteristics such as romantic love( amativeness) and combativeness were assigned to the back of the brain. even the most abstract of human behaviors–generosity, secretiveness, and religiosity–were assigned a spot in the brain( figure 1-1)

8

in 1823 Flourens wrote:”all perceptions, all volitions occupy the same seat in these( cerebral) organs; the faculty of perceiving, of conceiving, of willing merely constitutes therefore a faculty which is essentially one”

the rapid acceptance of this belief, later called the holistic view of the brain, was based only partly on Flourens’s experimental work. it also represented a culture reaction against the materialistic view that the human mind is a biological organ. it represented a rejection of the notion that there is no soul, that all mental processes can be reduced to activity within the brain, and that the mind can be improved by exercising it, ideas that were unacceptable to the religious establishment and landed aristocracy of Europe

8

the holistic view was seriously challenged, however, inthe mid-19th century by the French neurologist Paul Pierre Broca, the German neurologist Carl Wernicke, and the British neurologist Hughlings Jackson. for example, in his studies of focal epilepsy, a disease characterized by convulsions that begin in a particular part of the body, Jackson showed that different motor and sensory functions could be traced to specific parts of the cerebral cortex. the regional studies of Broca, Wernicke, and Jackson were extended to the cellular level by Charles Sherrington and by Ramon y Cajal, who championed the view of brain function called cellular connectionism. according to this view individual neurons are the signaling units of the brain; they are arranged in functional groups and connect to one another in a precise fashion. Wernicke’s work and that of the French neurologist Jules Dejerine is particular revealed that different behaviors are produced by different interconnected brain regions

the brain has distinct functional regions

9

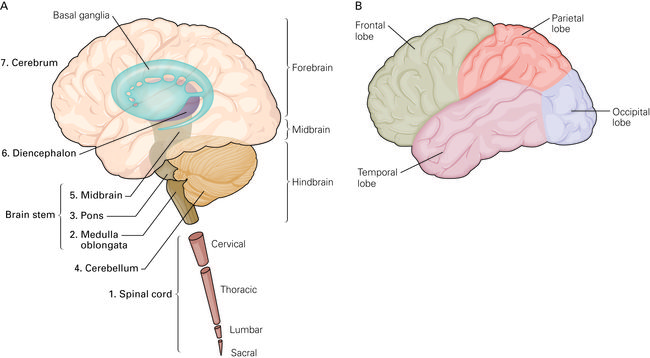

the central nervous system is a bilateral and essentially symmetrical structure with two main parts, the spinal cord and the brain. the brain comprises seven major structures: the medulla oblongata, pons, cerebellum, midbrain, diencephalon, and cerebrum

9

such studies provide direct evidence that specific types of behavior involve particular regions of the brain. as a result, Gall’s original idea that discrete regions are specialized for different functions is now one of the cornerstones of modern brain science

10

each lobe has a specialized set of functions. the frontal lobe is largely concerned with short-term memory and planning future actions and with control of movement; the parietal lobe with somatic sensation, with forming a body image and relating it to extrapersonal space; the occipital lobe with vision; and the temporal lobe with hearing and–through its deep structures, the hippocampus and amygdaloid nuclei–with learning, memory, and emotion

10

two important features characterize the organization of the cerebral cortex. first, each hemisphere is concerned primarily with sensory and motor processes on the contralateral( opposite) side of the body. thus sensory information that reaches the spinal cord from the left side of the body crosses to the right side of the nervous system on its way to the cerebral cortex. similarly, the motor areas in the right hemisphere exert control over the movements of the left half of the body. the second feature is that the hemispheres, although similar in appearance, are neither completely symmetrical in structure nor equivalent in function

the first strong evidence for localization of cognitive abilities came from studies of language disorders

11

in most people, therefore, the left hemisphere is regarded as dominant

11

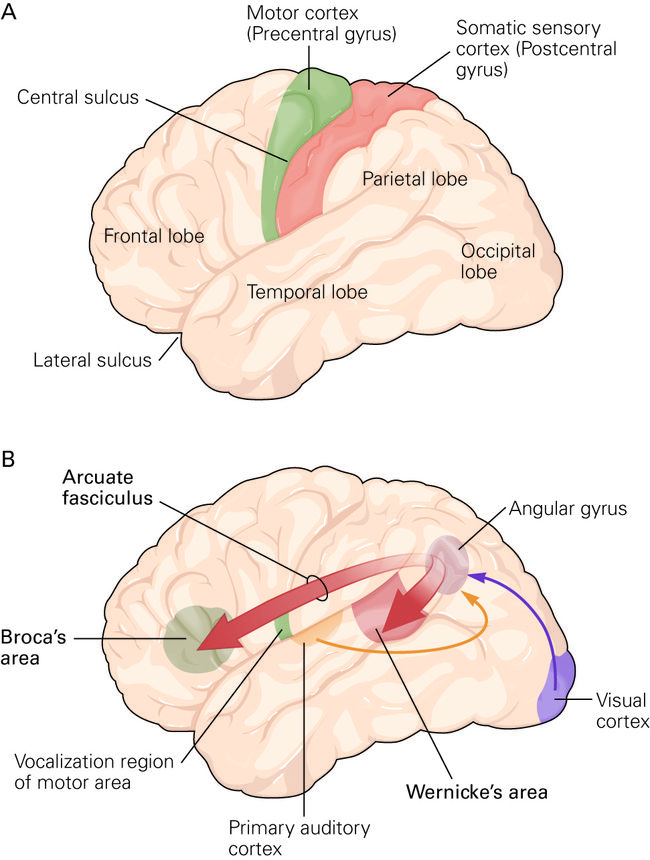

Wernicke described another type of aphasia, a failure of comprehension rather than speech: a receptive as opposed to an expressive malfunction. whereas Broca’s patients could understand language but not speak, Wernicke’s patient could form words but could not understand language. moreover, the locus of this new type of aphasia was different from that described by Broca: the lesion occurred in the posterior part of the cortex where the temporal lobe meets the parietal and occipital lobes

B areas involved in language. Wernicke’s area processes auditory input for language and is important for understanding speech. it lies near the primary auditory cortex and the angular gyrus, which combines auditory input with information from other senses. Broca’s area controls the production of intelligible speech. it lies near the region of the motor area that controls the mouth and tongue movements that form words. Wernicke’s area communicates with Broca’s area by a bidirectional pathway, part of which is made up of the arcuate fasciculus

on the basis of this discovery, and the work of Broca, Fritsch, Hitzig, Wernicke formulated a neural model of language that attempted to reconcile and extend the two predominant theories of brain function at that time. phrenologists and cellular connectionists argued that the cortex was a mosaic of functionally specific areas, whereas the holistic aggregate-field school claimed that every mental function involved the entire cerebral cortex. Wernicke proposed that only the most basic mental functions, those concerned with simple perceptual and motor activities, are mediated by neurons in discrete local areas of the cortex. more complex cognitive functions, he argued, result from interconnections between several functional sites. in placing the principle of localized function within a connectionist framework, Wernicke realized that different components of a single behavior are likely to be processed in several regions of the brain. he was thus the first to advance the idea of distributed processing, now a central tenet of neural science

Wernicke postulated that language involves separate motor and sensory programs, each governed by distinct regions of cortex. he proposed that the motor program that governs the mouth movements for speech is located in Broca’s area, suitably situated in front of that region of the motor area that controls the mouth, tongue, palate, and vocal cords( figure above B). he next assigned the sensory program that governs word perception to the temporal-lobe area that he had discovered, which is now called Wernicke’s area. this region is conveniently surrounded by the auditory cortex and by areas now known collectively as association cortex, a region of cortex that integrates auditory, visual, and somatic sensations

thus Wernicke formulated the first coherent neural model for language that–with important modifications and elaborations we shall encounter in chapter 60–is still useful today. according to this model, the initial steps in neural processing of spoken or written words occur in separate sensory areas of the cortex specialized for auditory or visual information. this information is then conveyed to a cortical association area, the angular gyrus, specialized for processing both auditory and visual information. here, according to Wernicke, spoken or written words are transformed into a neural sensory code shared by both speech and writing. this representation is conveyed to Wernicke’s area, where it is recognized as language and associated with meaning. it is also relayed to Broca’s area, which contains the rules, or grammar, for transforming the sensory representation into a motor representation that can be realized as spoken or written language. when this transformation form sensory to motor representation cannot take place, the patient loses the ability to speak and write

the power of Wernicke’s model was not only its completeness but also its predictive utility. this model correctly predicted a third type of aphasia, one that results from disconnection. here the receptive and expressive zones for speech are intact, but the neuronal fibers that connect them are destroyed. this conduction aphasia, as it is now called, is characterized by an incorrect use of words( paraphasia). patients with conduction aphasia understand words that they hear and read and have no motor difficulties when they speak. yet they cannot speak coherently; they omit parts of words or substitute incorrect sounds and in particular they have difficulties repeating phrases. although painfully aware of their own errors, they are unable to put them right

13

as we shall see in later chapters, functional specialization is a key organizing principle in the cerebral cortex, extending even to individual columns of cells within a functional area. indeed, the brain is divided into many more functional regions than Brodmann envisaged

14

in separate studies, Joy Hirsch and her colleagues, and Mariacristina Musso, Andrea Moro, and their colleagues used fMRI to explore more deeply Wernicke’s idea that Broca’s area contains the grammatical rules of language. Hirsch and her colleagues made the interesting discovery that processing of one’s native language and processing of a second language occur in distinct regions within Broca’s area. if the second language is acquired in adulthood, it is represented in a region separate from that which represents the native language. if the second language is acquired early, however, both the native language and the second language are represented in a common region in Broca’s area. these studies indicate that the age at which a language is acquired is a significant factor in determining the functional organization of Broca’s area. in contrast there is no evidence of such separate processing of different languages in Wernicke’s area( figure followed):

functional magnetic resonance images of the brains of bilingual subjects during generation of narratives in two languages

these bilingual subjects were either “early” or “late” bilingual speakers; “early” bilinguals had learned two languages together prior to the age of 7 years, whereas “late” bilinguals acquired a second language after age 11 years. axial slices of brain that intersect Broca’s area are shown for one representative “early” bilingual subject and one representative “late” bilingual subject. regions of the brain that responded during the narrative tasks are shown in red( native language) and yellow( native and second language). in high-resolution views of these areas centroids of activity associated with each language are indicated by(+) and areas of overlap between the two areas are shown in orange

A. in the early bilingual subject the locations of the centers and spread of activity for both languages are indistinguishable at the resolution of functional magnetic resonance imaging( fMRI)(1.5*1.5 mm) as indicated by the close proximity of the two (+) and the orange region indicating sensitivity to both languages

B. in the late bilingual subject both the locations of the centers (+) and the spread of the native and second language are distinguishable at the same resolution

15

because language is a uniquely human capability, Charles Darwin suggested that the acquisition of language is an inborn instinct comparable to that for upright posture

15

based on an analysis of the structure of sentences ion various languages, Chomsky argued that all natural languages share a common design, which he called universal grammar. the existence of universal grammar, he argued, implies that there is an innate system in the human brain that evolved to mediate this grammatical design of language

this, of course, raised the question: where in the brain does such a system reside? is it in Broca’s area, as Wernicke’s model would suggest? Musso, Moro, and their colleagues asked this question and found that the region of Broca’s area concerned with second language becomes established and increases in activity only when an individual learns a second language that is “natural”, that is, one that shares the universal grammar. if the second language is an artificial language, a language that violates the rules of universal grammar, activity in Broca’s area does not increase. thus Broca’s area must contain some kind of constraints that determine the structure of all natural languages

16

these observations illustrate three points. first, the cognitive processing for language occurs in the left hemisphere and is independent of pathways that process the sensory and motor modalities used in language. second, fully functioned auditory and motor systems are not necessary conditions for the emergence and operation of language capabilities in the left hemisphere. third, spoken language represents only one of a family of language skills mediated by the left hemisphere

similar conclusions that the brain has distinct cognitive systems have been reached from investigations of behaviors other than language. these studies demonstrate that complex information processing requires many distinct but interconnected cortical and sub-cortical areas, each concerned with processing some particular aspects of sensory stimuli or motor movement and not others. for example, in the visual system, a dorsal cortical pathway is concerned with where an object is located in the external world while a ventral pathway is concerned with what that object is

affective states are also mediated by local, specialized systems in the brain

16

despite the persuasive evidence for localized systems in the cortex dedicated to language, the idea nevertheless persisted that affective( emotional) functions could not be mediated by discrete specialized systems. emotion, it was believed, must be an expression of whole-brain activity. only recently has this view been modified. although the neural systems governing emotion have not been mapped as precisely as the sensory, motor, and cognitive systems, distinct emotions can be elicited by stimulating specific parts of the brain in humans or experimental animals. the localization of neural systems regulating emotion has been dramatically demonstrated in patients with certain language disorders and in patients with a particular type of epilepsy that affects the regulation of affective states

some aphasic patients not only manifest cognitive defects in language but also have trouble with the affective aspects of language, such as intonation( prosody). these affective aspects are represented in the right hemisphere and, rather strikingly, the neural organization of the affective elements of language mirrors the organization of language in the left hemisphere. damage to the right temporal area corresponding to disturbances in comprehending emotional aspects of speech, for example the ability to appreciate from a person’s tone of voice whether he is describing a sad or happy event. in contrast, damage to the right frontal area corresponding to Broca’s area also leads to difficulty in expressing emotional aspects of speech

thus some neurons needed for language also exist in the right hemisphere. indeed, there is now considerable evidence that an intact right hemisphere is necessary to appreciate semantic subtleties of language, such as irony, metaphor, and wit, as well as the emotional content of speech. there is also preliminary evidence that the ability to enjoy and perform music involves systems in the right hemisphere

aprosodias, disorders of affective aspects of language that are localized to the right hemisphere, are classified as sensory, motor, or conductive, following the classification used for aphasias

although the localization of language appears to be inborn, it is by no means completely determined until the age of seven or eight. young children in whom the left cerebral hemisphere is severely damaged early in life can still develop an essentially normal grasp of language, but they do so at a cost, for the ability of these children to locate objects in space or to reason spatially is much reduced compared to that of normal children

17

finally, one other important structure involved in the regulation of emotion is the amygdala, which lies deep within the cerebral hemispheres

mental processes are the end product of the interactions between elementary processing units in the brain

17

there are several reasons why the evidence for the localization of brain functions, which seems so obvious and compelling in retrospect, had been rejected so often in the past. phrenologists introduced the idea of localization in an exaggerated form and without adequate evidence. they imagined each region of the cerebral cortex as an independent mental organ dedicated to a complete and distinct aspect of personality, much as the pancreas and the liver are independent digestive organs. Flourens’s rejection of phrenology and the ensuing dialectic between proponents of the aggregate-field view( against localization) and the cellular connectionists( for localization) were responses to a theory that was simplistic and without adequate experimental evidence

in the aftermath of Wernicke’s discovery of the modular organization of language in the brain–interconnected serial and parallel processing centers with more-or-less independent functions–we now think that all cognitive abilities result from the interaction of many processing mechanisms distributed in several regions of the brain. specific brain regions are not responsible for specific mental faculties but instead are elementary processing units. perception, movement, language, thought,and memory are all made possible by the interlinkage of serial and parallel processing in discrete brain regions, each with specific functions. as a result, damage to a single area need not result in the complete loss of a cognitive function( or faculty) as many earlier neurologists believed. even if a behavior initially disappears, it may partially return as undamaged parts of the brain reorganize their linkages

thus it is not accurate to think of a mental process as being mediated by a chain of nerve cells connected in series–one cell connected directly to the next–for in such an arrangement the entire process breaks down when a single connection is disrupted. a more realistic metaphor is that of a process consisting of several parallel pathways in a communications network that can interact and ultimately converge upon a common set of target cells. the malfunction of a single pathway affects the information carried by it but need not disrupt the entire system. the remaining parts of the system can modify their performance to accommodate the breakdown of one pathway

modular processing in the brain was slow to be accepted because, until recently, it was difficult to demonstrate which components of a mental operation a particular pathway or brain region represented. nor is it easy to define mental operations in a manner that leads to testable hypotheses. only during the last several decades, with the convergence of modern cognitive psychology and the brain sciences, have we begun to appreciate that all mental functions can be broken down into subfunctions

to illustrate this point, consider how we learn, store, and recall information about objects, people, and events. simple introspection suggests that we store each piece of our knowledge as a single representation that can be recalled by memory-jogging stimuli or even by the imagination alone. everything you know about your grandmother, for example, seems to be stored in memory. knowledge about grandmother is not stored as a single representation but rather is subdivided into distinct categories and stored separately. one region of the brain stores information about the invariant physical features that trigger your visual recognition of her. information about changeable aspects of her face–her expression and lip movements that relate to social communication–is stored in another region. the ability to recognize her voice is mediated in yet another region

the most astonishing example of the modular organization of mental processes is the finding that our very sense of self–a self-aware coherent being, the sum of what we mean when we say “I”–is achieved through the connection of independent circuits in our two cerebral hemispheres, each mediating its own sense of awareness. the remarkable discovery that even consciousness is not a unitary process was made by Roger Sperry, Michael Gazzaniga, and Joseph Bogen in the course of studying patients in whom the corpus callosum–the major tract connecting the two cerebral hemispheres–was severed as a treatment for epilepsy. they found that each hemisphere had a consciousness that was able to function independently of the other

thus while one patient was reading a favorite book held in his left hand, the right hemisphere, which controls the left hand but cannot read, found that simply looking at the book was boring. the right hemisphere commanded the left hand to put the book down! another patient would put on his clothes with the left hand while taking them off with the other. each hemisphere has a mind of its own! in addition, the dominant hemisphere sometimes commented on the performance of the nondominant hemisphere, frequently manifesting a false sense of confidence regarding problems to which it could not know the solution, as the information was provided exclusively to the nondominant hemisphere

such studies have brought the study of consciousness to center stage in neural science. as we shall learn in chapters 19, 20, and 61, consciousness, including self-consciousness, once the domain of philosophy, has been studied by neurobiologists such as Francis Crick, Christof Koch, Gerald Edelman, and Stanislas Dehaene. neurobiologists do not concern themeselves with the issue of subjectivity in conscious experience. Crick and Koch have focused on what they considered to be the simplest manifestation of consciousness: selective attention in visual perception. they believe a special and restricted population of neurons–perhaps only a few thousand cells–are responsible for this component. by contrast, Dehaene and Edelman believe that consciousness is a global property of the brain that involves vast numbers of nerve cells and a complex system of feed-forward broadcasting and feedback reentrant circuits

as these examples illustrate, the main reason it has taken so long to appreciate which higher mental activities are mediated by particular regions of the brain is that we are dealing with biology’s deepest riddle: the neural representation of consciousness and self-awareness. to be able to study the relationship between a mental process and specific brain regions, we must first identify the components of the mental process that we are attempting to explain. of all behaviors, however, the higher mental processes are the most difficult to describe, to measure objectively, and to break down into elementary components. in addition, the brain’s anatomy is immensely complex, and the structure and interconnections of its many parts are still not fully understood

to analyze how a specific mental activity is processed in the brain, we must determine not only which aspects of the activity occur in which regions of the brain, but also how the mental activity is represented. only in the last decade has this because possible. by combining the conceptual tools of cognitive psychology with new physiological techniques and brain-imaging methods, we are beginning to visualize the regions of the brain involved in particular behaviors. and we are beginning to discern how these behaviors can be described by a set of simpler mental operations and mapped to interconnected areas of the brain. indeed, the excitement evident in neural science today stems from the conviction that at last we have the proper tools to explore empirically the organ of mental function and eventually to fathom the biological principles that underlie human behavior