作者:Nate Silver

来源:新浪微盘 mobi格式

推荐人:张伟 去哪儿产品

对于中国读者,纳特·西尔弗有点陌生。他最重要的预测领域是棒球和美国政治投票,这两者我们都不熟悉。在美国,他真正成名也是从2008年对总统大选的预测开始的。这还要从美国大选的制度说起。美国大选虽然是全体公民一人一票,但是在决定总统是谁方面却有点复杂:大多数州都会分别统计本州的选票,超过半数的选举人将在这一州获胜,而一旦获胜就会获得该州所有的选举人票。之后在计算选举人票之和,超过半数的候选人将当选总统。先不用管这个有点复杂的制度,我们只需要得知,在美国大选中,不仅有最后的选举输赢决定谁来入主白宫,每一个州也都会得到一个候选人是否获胜的结果。而纳特·西尔弗正是在2008年成功预测了50个州中49个的选举结果。

2008年大选是西尔弗的关注者从棒球迷到全体公众的引爆点。2007年,还在为棒球杂志写作的西尔弗开始撰写一个政治分析专栏,这个专栏又演变成了538网站。他的分析文章开始受到追捧,纽约时报的政治专栏也会引用。随着大选来临,网站吸引了很多目光。因为时差的缘故,各州大选的记票并不是同时开始和结束的。随着一个个州公布结果,西尔弗的结果引发了狂潮。最终,只有印第安纳州一州错误,49个州的预测全部正确。之后的事情让西尔弗走上了超级名人之路:企鹅出版社重金签约书稿,纽约时报开设政治专栏把538直接移到了自己的网站上,TED 大会邀请他演讲。他不再是那个玩棒球数据的极客,而是一个神人,居然能预测总统大选。注意,不是谁能获胜,而是50个州,谁在哪一个州获胜。剩下的问题只有一个了:他的传奇能延续么?能。2012年的有一次大选,西尔弗在50个州的预测都对了。

张伟同学半年前在一次分享活动上推荐的两本书之一,上一本《数据化决策》读的我如痴如醉,而这一本则相对而言没有那么舒服,因为在锻炼英语阅读,所以没有找翻译版,文字上觉得比较冗余,完全可以缩减到1/3,还有就是出版时间的原因,书里面的很多内容已经被其他的很多渠道分解和剧透了,书读的不细,摘录的也不平衡。

书的核心观点和《数据化决策》一样,在于统计学对决策的重要价值层面,相对而言《数据化决策》提供了更多更全面的方法论,而《The Signal and the Noise》没有那么多的理论,把故事和方法结合在一起是书的特点,看过之后可能会对故事映像更深而忽略掉了方法。

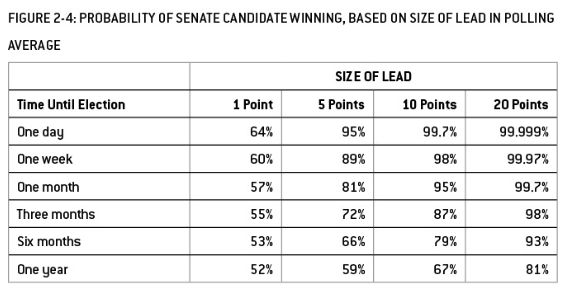

比如美国职棒联盟相关的文字中提到的《点球成金》在看过电影的人眼中就介绍的有些多了,天气预报系统的故事,意大利的某处地震等等都不具有那么精细的描述价值,读的我昏昏欲睡。作者对大选的神预测方法论也不复杂,主要是数据分析的方式(后面摘录了分析表格数据),不过毕竟作者是独立做出的研究,还是非常了不起,被他娓娓道来我也就认了:)

传统风险管控机制的数理分析机制的问题在于:你喝酒的概率是1%,你自己开车的概率是5%,并不代表你酒驾的概率是万分之五,传统的风险评估方式产生(评估机构往往会使用的方式)的错误就在于此,事实上在某些外部环境之下你同时喝酒和驾车的概率是50%以上。

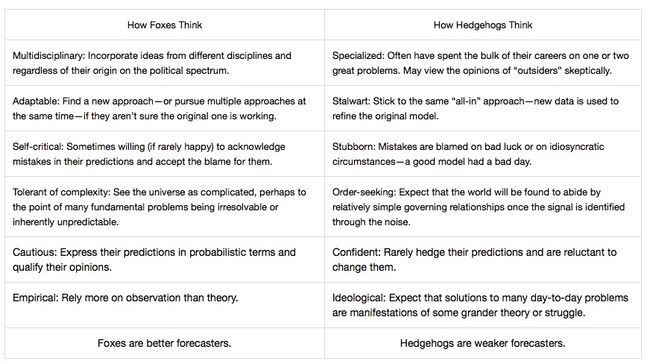

关于狐狸和刺猬的决策比喻比较有意思,下面表格有摘录,觉得狐狸和刺猬各有各的决策专属领域,不过依然很认可作者的分析,狐狸可以通过和很多刺猬的交流来获得更准确的决策,而刺猬的决策局限性在狐狸的层面上是很明显的。

天气预报的时候如果是5%的下雨,不敢说5%,而要说20%,对于预期好或者不好的判断是一种社会现象,准确性的层面以外还需要考虑社会心理层面,这个对于企业管理、新闻发布等等都有启发和借鉴。

摘录:

The idea of man as master of his fate was gaining currency. The words predict and forecast are largely used interchangeably today, but in Shakespeare’s time, they meant different things. A prediction was what the soothsayer told you; a forecast was something more like Cassius’s idea.

The forecasting models published by political scientists in advance of the 2000 presidential election predicted a landslide 11-point victory for Al Gore.38 George W. Bush won instead. Rather than being an anomalous result, failures like these have been fairly common in political prediction. A long-term study by Philip E. Tetlock of the University of Pennsylvania found that when political scientists claimed that a political outcome had absolutely no chance of occurring, it nevertheless happened about 15 percent of the time. (The political scientists are probably better than television pundits, however.)

In this book, I’ll discuss the danger of “unknown unknowns”—the risks that we are not even aware of. Perhaps the only greater threat is the risks we think we have a handle on, but don’t.

“The major difference between a thing that might go wrong and a thing that cannot possibly go wrong is that when a thing that cannot possibly go wrong goes wrong it usually turns out to be impossible to get at or repair,” wrote Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series.

kerlof wrote a famous paper on this subject called “The Market for Lemons”78—it won him a Nobel Prize. In the paper, he demonstrated that in a market plagued by asymmetries of information, the quality of goods will decrease and the market will come to be dominated by crooked sellers and gullible or desperate buyers.

You’re also not much of a drinker, and one of the things you’ve absolutely never done is driven drunk. But one year you get a little carried away at your office Christmas party. A good friend of yours is leaving the company, and you’ve been under a lot of stress: one vodka tonic turns into about twelve. You’re blitzed, three sheets to the wind. Should you drive home or call a cab?

Foxes, Tetlock found, are considerably better at forecasting than hedgehogs. They had come closer to the mark on the Soviet Union, for instance. Rather than seeing the USSR in highly ideological terms—as an intrinsically “evil empire,” or as a relatively successful (and perhaps even admirable) example of a Marxist economic system—they instead saw it for what it was: an increasingly dysfunctional nation that was in danger of coming apart at the seams. Whereas the hedgehogs’ forecasts were barely any better than random chance, the foxes’ demonstrated predictive skill.

But polls do become more accurate the closer you get to Election Day. Figure 2-4 presents some results from a simplified version of the FiveThirtyEight Senate forecasting model, which uses data from 1998 through 2008 to infer the probability that a candidate will win on the basis of the size of his lead in the polling average. A Senate candidate with a five-point lead on the day before the election, for instance, has historically won his race about 95 percent of the time-almost a sure thing, even though news accounts are sure to describe the race as “too close to call.” By contrast, a five-point lead a year before the election translates to just a 59 percent chance of winning-barely better than a coin flip.

But it abided by three broad principles, all of which are very fox-like.

Principle 1: Think Probabilistically

Principle 2: Today’s Forecast Is the First Forecast of the Rest of Your Life

Principle 3: Look for Consensus

Foxes often manage to do inside their heads what you’d do with a whole group of hedgehogs,” Tetlock told me. What he means is that foxes have developed an ability to emulate this consensus process. Instead of asking questions of a whole group of experts, they are constantly asking questions of themselves. Often this implies that they will aggregate different types of information together—as a group of people with different ideas about the world naturally would—instead of treating any one piece of evidence as though it is the Holy Grail. (FiveThirtyEight’s forecasts, for instance, typically combine polling data with information about the economy, the demographics of a state, and so forth.) Forecasters who have failed to heed Tetlock’s guidance have often paid the price for it.

The meteorologists at the Weather Channel will fudge a little bit under certain conditions. Historically, for instance, when they say there is a 20 percent chance of rain, it has actually only rained about 5 percent of the time. In fact, this is deliberate and is something the Weather Channel is willing to admit to. It has to do with their economic incentives.